A Toolbox for Resilience and Adaptation in Coastal Arctic Alaska 2017 Guide for Alaska Communities, Tribes, Agencies and Citizens Strategies, Actions and Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center 2012 Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A. Bieniek University of Alaska Fairbanks, [email protected] Uma S. Bhatt University of Alaska Fairbanks Richard L. Thoman NOAA/National Weather Service/Weather Forecast Officea F irbanks Heather Angeloff University of Alaska Fairbanks James Partain NOAA/National Weather Service/Alaska Region See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Bieniek, Peter A.; Bhatt, Uma S.; Thoman, Richard L.; Angeloff, Heather; Partain, James; Papineau, John; Fritsch, Frederick; Holloway, Eric; Walsh, John E.; Daly, Christopher; Shulski, Martha; Hufford, Gary; Hill, David F.; Calos, Stavros; and Gens, Rudiger, "Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods" (2012). Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications. 15. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator -

Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends Over Pan-Arctic Tundra

Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 4229-4254; doi:10.3390/rs5094229 OPEN ACCESS Remote Sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Recent Declines in Warming and Vegetation Greening Trends over Pan-Arctic Tundra Uma S. Bhatt 1,*, Donald A. Walker 2, Martha K. Raynolds 2, Peter A. Bieniek 1,3, Howard E. Epstein 4, Josefino C. Comiso 5, Jorge E. Pinzon 6, Compton J. Tucker 6 and Igor V. Polyakov 3 1 Geophysical Institute, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 903 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Institute of Arctic Biology, Department of Biology and Wildlife, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, P.O. Box 757000, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (D.A.W.); [email protected] (M.K.R.) 3 International Arctic Research Center, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, College of Natural Science and Mathematics, 930 Koyukuk Dr., Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Virginia, 291 McCormick Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22904, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 Cryospheric Sciences Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Biospheric Science Branch, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 614.1, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (J.E.P.); [email protected] (C.J.T.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-907-474-2662; Fax: +1-907-474-2473. -

Spanning the Bering Strait

National Park service shared beringian heritage Program U.s. Department of the interior Spanning the Bering Strait 20 years of collaborative research s U b s i s t e N c e h UN t e r i N c h UK o t K a , r U s s i a i N t r o DU c t i o N cean Arctic O N O R T H E L A Chu a e S T kchi Se n R A LASKA a SIBERIA er U C h v u B R i k R S otk S a e i a P v I A en r e m in i n USA r y s M l u l g o a a S K S ew la c ard Peninsu r k t e e r Riv n a n z uko i i Y e t R i v e r ering Sea la B u s n i CANADA n e P la u a ns k ni t Pe a ka N h las c A lf of Alaska m u a G K W E 0 250 500 Pacific Ocean miles S USA The Shared Beringian Heritage Program has been fortunate enough to have had a sustained source of funds to support 3 community based projects and research since its creation in 1991. Presidents George H.W. Bush and Mikhail Gorbachev expanded their cooperation in the field of environmental protection and the study of global change to create the Shared Beringian Heritage Program. -

BSIERP B69 Appendix

Technical Paper No. 371 Subsistence Harvests and Uses in Three Bering Sea Communities, 2008: Akutan, Emmonak, and Togiak by James A. Fall, Caroline L. Brown, Nicole M. Braem, Lisa Hutchinson-Scarbrough, David Koster, Theodore M. Krieg, and Andrew R. Brenner December 2012 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the reports by the Division of Subsistence. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics centimeter cm Alaska Administrative Code AAC all standard mathematical signs, symbols deciliter dL all commonly-accepted and abbreviations gram g abbreviations e.g., alternate hypothesis HA hectare ha Mr., Mrs., base of natural logarithm e kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. catch per unit effort CPUE kilometer km all commonly-accepted coefficient of variation CV liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., common test statistics (F, t, 2, etc.) meter m R.N., etc. confidence interval CI milliliter mL at @ correlation coefficient (multiple) R millimeter mm compass directions: correlation coefficient (simple) r east E covariance cov Weights and measures (English) north N degree (angular ) ° cubic feet per second ft3/s south S degrees of freedom df foot ft west W expected value E gallon gal copyright greater than > inch in corporate suffixes: greater than or equal to mile mi Company Co. -

Population Monitoring and Status of the Nushagak Peninsula Caribou Herd

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Population Monitoring and Status of the Nushagak Peninsula Caribou Herd, 1988-2012 Andy R. Aderman Togiak National Wildlife Refuge Dillingham, Alaska August 2013 Citation: Aderman, A. R. 2013. Population monitoring and status of the Nushagak Peninsula caribou herd, 1988-2012. Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, Dillingham, Alaska. 30 pp. Keywords: caribou, Rangifer tarandus, Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, southwestern Alaska, calf production, recruitment, survival, population estimate, subsistence harvest, management implications Disclaimer: The use of trade names of commercial products in this report does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the federal government. Population Monitoring and Status of the Nushagak Peninsula Caribou Herd, 1988-2012 Andy R. Aderman1 ABSTRACT In February 1988, 146 caribou were reintroduced to the Nushagak Peninsula. From 1988 to 2013, radio collars were deployed on female caribou and monitored monthly. High calf recruitment and adult female survival allowed the population to grow rapidly (r = 0.226), peaking at 1,399 caribou in 1997. Population density on the Nushagak Peninsula reached approximately 1.2 caribou per km2 in 1997 and 1998. During the next decade, calf recruitment and adult female survival decreased and the population declined (r = -0.105) to 546 caribou in 2006. The population remained at about 550 caribou until 2009 and then increased to 902 by 2012. Subsistence hunting removed from 0-12.3% of the population annually from 1995-2012. Decreased nutrition and other factors likely caused an unstable age distribution and subsequent population decline after the peak in 1997. Dispersal, disease, unreported harvest and predation implications for caribou populations are discussed. -

Climate Change in Alaska

CLIMATE CHANGE ANTICIPATED EFFECTS ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES AND POTENTIAL ACTIONS BY THE ALASKA REGION, U.S. FOREST SERVICE Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 This report should be referenced as: Haufler, J.B., C.A. Mehl, and S. Yeats. 2010. Climate change: anticipated effects on ecosystem services and potential actions by the Alaska Region, U.S. Forest Service. Ecosystem Management Research Institute, Seeley Lake, Montana, USA. Cover photos credit: Scott Yeats i Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Regional Overview- Alaska Region ..................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Ecosystem Services of the Southcentral and Southeast Landscapes ................................................. 5 4.0 Climate Change Threats to Ecosystem Services in Southern Coastal Alaska ..................................... 6 . Observed changes in Alaska’s climate ................................................................................................ 6 . Predicted changes in Alaska climate .................................................................................................. 7 5.0 Impacts of Climate Change on Ecosystem Services ............................................................................ 9 . Changing sea levels ............................................................................................................................ -

Arctic Report Card 2018 Effects of Persistent Arctic Warming Continue to Mount

Arctic Report Card 2018 Effects of persistent Arctic warming continue to mount 2018 Headlines 2018 Headlines Video Executive Summary Effects of persistent Arctic warming continue Contacts to mount Vital Signs Surface Air Temperature Continued warming of the Arctic atmosphere Terrestrial Snow Cover and ocean are driving broad change in the Greenland Ice Sheet environmental system in predicted and, also, Sea Ice unexpected ways. New emerging threats Sea Surface Temperature are taking form and highlighting the level of Arctic Ocean Primary uncertainty in the breadth of environmental Productivity change that is to come. Tundra Greenness Other Indicators River Discharge Highlights Lake Ice • Surface air temperatures in the Arctic continued to warm at twice the rate relative to the rest of the globe. Arc- Migratory Tundra Caribou tic air temperatures for the past five years (2014-18) have exceeded all previous records since 1900. and Wild Reindeer • In the terrestrial system, atmospheric warming continued to drive broad, long-term trends in declining Frostbites terrestrial snow cover, melting of theGreenland Ice Sheet and lake ice, increasing summertime Arcticriver discharge, and the expansion and greening of Arctic tundravegetation . Clarity and Clouds • Despite increase of vegetation available for grazing, herd populations of caribou and wild reindeer across the Harmful Algal Blooms in the Arctic tundra have declined by nearly 50% over the last two decades. Arctic • In 2018 Arcticsea ice remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past. The 12 lowest extents in Microplastics in the Marine the satellite record have occurred in the last 12 years. Realms of the Arctic • Pan-Arctic observations suggest a long-term decline in coastal landfast sea ice since measurements began in the Landfast Sea Ice in a 1970s, affecting this important platform for hunting, traveling, and coastal protection for local communities. -

Climate Change Impacts in Anchorage

MARCH 2016 STRENGTHENING RESILIENCE CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS IN ANCHORAGE Located in Southcentral Alaska, Anchorage is the most losses from extreme events, and threats to the health and populated area of the state and its economic hub, home safety of their employees. The business community in to about 300,000 people, or about half of the state’s resi- Anchorage can work together with city and state agen- dents.1 Energy production is the main driver of the state’s cies, along with other stakeholders to evaluate potential economy, although minerals, seafood, tourism, and agri- risks and take steps toward enhancing the community’s culture also contribute. Many oil and gas companies are resilience. headquartered in Anchorage.2 Anchorage is the state’s primary transportation, communications, trade, service, TEMPERATURE and finance center. The local economy is driven mostly by oil and gas, the military, transportation, and the tour- As a state, Alaska has warmed at more than twice the rate ism industry. The Port of Anchorage serves as the state’s of the rest of the United States, with state-wide average shipping hub. annual temperature increasing by 3°F and average winter temperature increasing by 6°F over the past 60 years.4 Anchorage is a diverse community, with minority groups representing 34 percent of its population and Temperature changes in Anchorage have been similar showing significant growth in these groups (including to the statewide average, with average annual tempera- Asian, Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Native groups, African ture increasing by 3.2°F and winter temperatures increas- American, and other races). -

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health ANTHC Center for Climate and Health Funded by Report prepared by: Michael Brubaker, MS Raj Chavan, PE, PhD ANTHC recognizes all of our technical advisors for this report. Thank you for your support: Gloria Shellabarger, Kiana Tribal Council Mike Black, ANTHC Linda Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Brad Blackstone, ANTHC Dale Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Jay Butler, ANTHC Sharon Dundas, City of Kiana Eric Hanssen, ANTHC Crystal Johnson, City of Kiana Oxcenia O’Domin, ANTHC Brad Reich, City of Kiana Desirae Roehl, ANTHC John Chase, Northwest Arctic Borough Jeff Smith, ANTHC Paul Eaton, Maniilaq Association Mark Spafford, ANTHC Millie Hawley, Maniilaq Association Moses Tcheripanoff, ANTHC Jackie Hill, Maniilaq Association John Warren, ANTHC John Monville, Maniilaq Association Steve Weaver, ANTHC James Berner, ANTHC © Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), October 2011. Funded by United States Indian Health Service Cooperative Agreement No. AN 08-X59 Through adaptation, negative health effects can be prevented. Cover Art: Whale Bone Mask by Larry Adams TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 Introduction 5 Community 7 Climate 9 Air 13 Land 15 Rivers 17 Water 19 Food 23 Conclusion 27 Figures 1. Map of Maniilaq Service Area 6 2. Google Maps view of Kiana and region 8 3. Mean Monthly Temperature Kiana 10 4. Mean Monthly Precipitation Kiana 11 5. Climate Change Health Assessment Findings, Kiana Alaska 28 Appendices A. Kiana Participants/Project Collaborators 29 B. Kiana Climate and Health Web Resources 30 C. General Climate Change Adaptation Guidelines 31 References 32 Rural Arctic communities are vulnerable to climate change and residents seek adaptive strategies that will protect health and health infrastructure. -

Overview of Environmental and Hydrogeologic Conditions at Barrow, Alaska

Overview of Environmental and Hydrogeologic Conditions at Barrow, Alaska By Kathleen A. McCarthy U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 94-322 Prepared in cooperation with the FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Anchorage, Alaska 1994 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report may be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 4230 University Drive, Suite 201 Open-File Reports Section Anchorage, AK 99508-4664 Box25286, MS 517 Federal Center Denver, CO 80225-0425 CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................. 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Physical setting ............................................................ 2 Climate .............................................................. 2 Surficial geology....................................................... 4 Soils................................................................. 5 Vegetation and wildlife.................................................. 6 Environmental susceptibility.............................................. 7 Hydrology ................................................................ 8 Annual hydrologic cycle ................................................. 9 Winter........................................................... 9 Snowmelt period................................................... 9 Summer......................................................... -

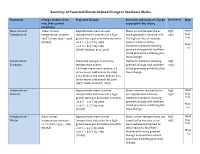

Summary of Expected Climate-‐Related Change in Southeast Alaska

Summary of Expected Climate-Related Change in Southeast Alaska Parameter Change to date (if no Projected Change Direction and range of change Confidence Map info, then current expected in the future condition) Mean Annual Mean annual Approximate mean annual Mean annual temperatures High SNAP Temperature temperature increase: temperature increases for a high are expected to increase with >95% Map +0.8°C from 1943 – 2005 greenhouse gas emissions scenario: the highest rate of increase Tool (NOAA) +0.5°C – 3.5°C by 2050 seen in winter months. Maps +2.0°C – 6.0°C by 2100 Northern mainland showing 1-3 (SNAP; Wolken et al. 2011) greatest change and southern island provinces exhibiting the least change. Temperature – Projected changes in extreme Northern mainland showing High Extremes temperature events: greatest change and southern >95% 3-6 times more warm events; 3-5 island provinces exhibiting the times fewer cold events by 2050. least change. 5-8.5 times more warm events; 8-12 times fewer cold events by 2100. (NPS; Timlin & Walsh, 2007) Temperature – Approximate mean summer Mean summer temperatures High SNAP Summer temperature increases for a high are expected to increase. >95% Map greenhouse gas emissions scenario: Northern mainland showing Tool +0.5°C – 2.0°C by 2050 greatest change and southern Maps +2.0°C – 5.5°C by 2100 island provinces exhibiting the 4-6 (SNAP) least change. Temperature – Mean winter Approximate mean winter Mean winter temperatures are High SNAP Winter temperature increase: temperature increases for a high expected to increase at an >95% Map +1.1°C from 1943 – 2005 greenhouse gas emissions scenario: elevated level compared to Tool (NOAA) +1.0°C – 3.5°C by 2050 other seasons. -

Counterclockwise Rotation of the Arctic Alaska Plate: Best Available Model Or Untenable Hypothesis for the Opening of the Amerasia Basin

Polarforschung 68: 247 - 255, 1998 (erschienen 2000) Counterclockwise Rotation of the Arctic Alaska Plate: Best Available Model or Untenable Hypothesis for the Opening of the Amerasia Basin By Ashton F. Ernbry' THEME 13: The Amerasian Basin and Margins: New Devel discussed by LAWVER & SCOTESE (1990) in a comprehensive opments and Results review of the subject. Summary: For the past thirty years the most widely aeeepted model for the As discussed by LAWVER & SCOTESE (1990), most of the mod opening of Amerasia Basin of the Aretie Oeean has been that the basin openecl els have little support and some are clearly negated by the cur by eountereloekwise rotation of northern Alaska and acljaeent Russia (Aretie Alaska plate) away frorn the Canadian Aretie Arehipelago about a pole in the rent geologieal and geophysical data bases from the Amerasia Maekenzie Delta region. Reeently LANE (1997) has ealled this modcl into ques Basin and its margins. At the time when the LAWVER & SCOTESE tion. Thus it is worth reviewing the main data and arguments for and against the (1990) review was published only the counterclockwise model model to determine if indeed it is untenable as claimed by Lane, 01' is still the seemed to provide a reasonable explanation of available best available model. paleornagnetic, paleogeographic and tectonic data from the The main evidenee in favour of the modcl includes the alignment of diverse margins and geophysical data from the basin (Grantz et al. 1979, geologieal lineaments ancl the eoineiclenee of Alaskan, Valanginian paleo HALGEDAHL & JARRARD 1987, EMBRY 1990, LAWVER et al. 1990). magnetie poles with the eratonie one following plate restoration employing the rotation model.