Climate-Induced Displacement of Alaska Native Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center 2012 Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods Peter A. Bieniek University of Alaska Fairbanks, [email protected] Uma S. Bhatt University of Alaska Fairbanks Richard L. Thoman NOAA/National Weather Service/Weather Forecast Officea F irbanks Heather Angeloff University of Alaska Fairbanks James Partain NOAA/National Weather Service/Alaska Region See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Hydrology Commons, Other Earth Sciences Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Bieniek, Peter A.; Bhatt, Uma S.; Thoman, Richard L.; Angeloff, Heather; Partain, James; Papineau, John; Fritsch, Frederick; Holloway, Eric; Walsh, John E.; Daly, Christopher; Shulski, Martha; Hufford, Gary; Hill, David F.; Calos, Stavros; and Gens, Rudiger, "Climate Divisions for Alaska Based on Objective Methods" (2012). Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications. 15. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/droughtfacpub/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Drought -- National Drought Mitigation Center at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Drought Mitigation Center Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator -

Climate Change in Alaska

CLIMATE CHANGE ANTICIPATED EFFECTS ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES AND POTENTIAL ACTIONS BY THE ALASKA REGION, U.S. FOREST SERVICE Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 This report should be referenced as: Haufler, J.B., C.A. Mehl, and S. Yeats. 2010. Climate change: anticipated effects on ecosystem services and potential actions by the Alaska Region, U.S. Forest Service. Ecosystem Management Research Institute, Seeley Lake, Montana, USA. Cover photos credit: Scott Yeats i Climate Change Assessment for Alaska Region 2010 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Regional Overview- Alaska Region ..................................................................................................... 2 3.0 Ecosystem Services of the Southcentral and Southeast Landscapes ................................................. 5 4.0 Climate Change Threats to Ecosystem Services in Southern Coastal Alaska ..................................... 6 . Observed changes in Alaska’s climate ................................................................................................ 6 . Predicted changes in Alaska climate .................................................................................................. 7 5.0 Impacts of Climate Change on Ecosystem Services ............................................................................ 9 . Changing sea levels ............................................................................................................................ -

Climate Change Impacts in Anchorage

MARCH 2016 STRENGTHENING RESILIENCE CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS IN ANCHORAGE Located in Southcentral Alaska, Anchorage is the most losses from extreme events, and threats to the health and populated area of the state and its economic hub, home safety of their employees. The business community in to about 300,000 people, or about half of the state’s resi- Anchorage can work together with city and state agen- dents.1 Energy production is the main driver of the state’s cies, along with other stakeholders to evaluate potential economy, although minerals, seafood, tourism, and agri- risks and take steps toward enhancing the community’s culture also contribute. Many oil and gas companies are resilience. headquartered in Anchorage.2 Anchorage is the state’s primary transportation, communications, trade, service, TEMPERATURE and finance center. The local economy is driven mostly by oil and gas, the military, transportation, and the tour- As a state, Alaska has warmed at more than twice the rate ism industry. The Port of Anchorage serves as the state’s of the rest of the United States, with state-wide average shipping hub. annual temperature increasing by 3°F and average winter temperature increasing by 6°F over the past 60 years.4 Anchorage is a diverse community, with minority groups representing 34 percent of its population and Temperature changes in Anchorage have been similar showing significant growth in these groups (including to the statewide average, with average annual tempera- Asian, Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Native groups, African ture increasing by 3.2°F and winter temperatures increas- American, and other races). -

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health

Climate Change in Kiana, Alaska Strategies for Community Health ANTHC Center for Climate and Health Funded by Report prepared by: Michael Brubaker, MS Raj Chavan, PE, PhD ANTHC recognizes all of our technical advisors for this report. Thank you for your support: Gloria Shellabarger, Kiana Tribal Council Mike Black, ANTHC Linda Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Brad Blackstone, ANTHC Dale Stotts, Kiana Tribal Council Jay Butler, ANTHC Sharon Dundas, City of Kiana Eric Hanssen, ANTHC Crystal Johnson, City of Kiana Oxcenia O’Domin, ANTHC Brad Reich, City of Kiana Desirae Roehl, ANTHC John Chase, Northwest Arctic Borough Jeff Smith, ANTHC Paul Eaton, Maniilaq Association Mark Spafford, ANTHC Millie Hawley, Maniilaq Association Moses Tcheripanoff, ANTHC Jackie Hill, Maniilaq Association John Warren, ANTHC John Monville, Maniilaq Association Steve Weaver, ANTHC James Berner, ANTHC © Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), October 2011. Funded by United States Indian Health Service Cooperative Agreement No. AN 08-X59 Through adaptation, negative health effects can be prevented. Cover Art: Whale Bone Mask by Larry Adams TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary 1 Introduction 5 Community 7 Climate 9 Air 13 Land 15 Rivers 17 Water 19 Food 23 Conclusion 27 Figures 1. Map of Maniilaq Service Area 6 2. Google Maps view of Kiana and region 8 3. Mean Monthly Temperature Kiana 10 4. Mean Monthly Precipitation Kiana 11 5. Climate Change Health Assessment Findings, Kiana Alaska 28 Appendices A. Kiana Participants/Project Collaborators 29 B. Kiana Climate and Health Web Resources 30 C. General Climate Change Adaptation Guidelines 31 References 32 Rural Arctic communities are vulnerable to climate change and residents seek adaptive strategies that will protect health and health infrastructure. -

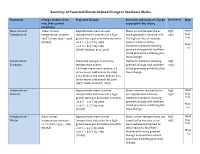

Summary of Expected Climate-‐Related Change in Southeast Alaska

Summary of Expected Climate-Related Change in Southeast Alaska Parameter Change to date (if no Projected Change Direction and range of change Confidence Map info, then current expected in the future condition) Mean Annual Mean annual Approximate mean annual Mean annual temperatures High SNAP Temperature temperature increase: temperature increases for a high are expected to increase with >95% Map +0.8°C from 1943 – 2005 greenhouse gas emissions scenario: the highest rate of increase Tool (NOAA) +0.5°C – 3.5°C by 2050 seen in winter months. Maps +2.0°C – 6.0°C by 2100 Northern mainland showing 1-3 (SNAP; Wolken et al. 2011) greatest change and southern island provinces exhibiting the least change. Temperature – Projected changes in extreme Northern mainland showing High Extremes temperature events: greatest change and southern >95% 3-6 times more warm events; 3-5 island provinces exhibiting the times fewer cold events by 2050. least change. 5-8.5 times more warm events; 8-12 times fewer cold events by 2100. (NPS; Timlin & Walsh, 2007) Temperature – Approximate mean summer Mean summer temperatures High SNAP Summer temperature increases for a high are expected to increase. >95% Map greenhouse gas emissions scenario: Northern mainland showing Tool +0.5°C – 2.0°C by 2050 greatest change and southern Maps +2.0°C – 5.5°C by 2100 island provinces exhibiting the 4-6 (SNAP) least change. Temperature – Mean winter Approximate mean winter Mean winter temperatures are High SNAP Winter temperature increase: temperature increases for a high expected to increase at an >95% Map +1.1°C from 1943 – 2005 greenhouse gas emissions scenario: elevated level compared to Tool (NOAA) +1.0°C – 3.5°C by 2050 other seasons. -

Assessment of the Potential Health Impacts of Climate Change in Alaska

Department of Health and Social Services Division of Public Health Editors Valerie J. Davidson, Commissioner Jay C. Butler, MD, Chief Medical Officer Joe McLaughlin, MD, MPH and Director Louisa Castrodale, DVM, MPH 3601 C Street, Suite 540 Local (907) 269-8000 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 http://dhss.alaska.gov/dph/Epi 24 Hour Emergency 1-800-478-0084 Volume 20 Number 1 Assessment of the Potential Health Impacts of Climate Change in Alaska Contributed by Sarah Yoder, MS, Alaska Section of Epidemiology January 8, 2018 Acknowledgments: We thank the following people for their contributions to this report: Dr. Sandrine Deglin and Madison Pachoe, Alaska Section of Epidemiology; Dr. Bob Gerlach, Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation; Dr. James Fall, Alaska Department of Fish and Game; Michael Brubaker, Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium; Dr. Robin Bronen, Alaska Institute for Justice; Dr. Tom Hennessey, CDC Arctic Investigations Program; and Dr. Ali Hamade, Dr. Paul Anderson, and Dr. Yuri Springer, former Alaska Section of Epidemiology staff. I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................... V Key Potential Adverse Health Impacts by Health Effect Category .............................................. VII Summary Recommendations ........................................................................................................... X 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ............................................................................................1 -

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, ALFRED J

MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW Editor, ALFRED J. HENRY ~ ____~~~~ ~ . ~ __ VOL. 58,No. 3 1930 CLOSEDMAY 3, 1930 W. B. No. 1012 MARCH, ISSUED MAY31, 1930 ____ THE CLIMATES OF ALASKA By EDITHM. FITTON [C‘lark University School of Geography] CONTENTS for Sitka, the Russian capital. Other nations, chiefly Introduction_____---_---------------------------------. the English and Americans, early sent ships of espIoration I. Factirs controlling Alaskan climates- - - - - -.-. - :g into Alaskan waters, and there are ecatt.ered meteoro- 11. Climatic elements- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - ST logical records available for various points where these Sunshine, cloudiness, and fog-- -_--__-----__--- 87 vessels winte,red along Alaskan shores (7, P. 137). Temperature- - - - - __ _____ - - - - - - - - - _____ - _____ 59 Alter the United States purchased Alaska, the United Length of frostless season.. - - - - - - - - - __ - - - - -.- - - States Army surgeons kept weather records in connection Winds and pressure _____._____________________:: January and July _-___-----.--________________91 with the post hospitals. “In 1878 and 1579, soon after Precipitation - - - -.- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 93 the orga,nization of the United Stat,e,s Weather Bureau, SnowfaU_____________________~_________-_____96 first under the Signal Corps of t’heArmy, later as a’bureau Days with precipitatioil- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 111. Seasonal conditions in the cliniatic provinces-_ - - - - 9”; of the nePartlne11t of &Ticulture, a feltrfirst-class observ- I A. Pacific coast and islsnds (marine) - - - - -_- - - - 98 ing stations, together mth several volunt,ary stations of I B. Pacific coast and islands (rain shadow)------ 99 lamer order, were established in Masl<a” (1, p, 133). 11. Bering Sea coast and islands (semi-ice marine) - 99 1917 appropriationof $l~,~~operlilit,ted the estab- 111. Arctic coast (ice-marine) - - - - - - - - - - - - - __ - - - an IV. -

REVIEW Economic Effects of Climate Change in Alaska

Economic Effects of Climate Change in Alaska Item Type Report Authors Berman, Matthew; Schmidt, Jennifer Publisher American Meteorological Society (AMS) Download date 26/09/2021 22:11:51 Link to Item https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-18-0056.1 VOLUME 11 WEATHER, CLIMATE, AND SOCIETY APRIL 2019 REVIEW Economic Effects of Climate Change in Alaska MATTHEW BERMAN AND JENNIFER I. SCHMIDT Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, Alaska Downloaded from http://journals.ametsoc.org/wcas/article-pdf/11/2/245/4879505/wcas-d-18-0056_1.pdf by guest on 09 June 2020 (Manuscript received 6 June 2018, in final form 19 November 2018) ABSTRACT We summarize the potential nature and scope of economic effects of climate change in Alaska that have already occurred and are likely to become manifest over the next 30–50 years. We classified potential effects discussed in the literature into categories according to climate driver, type of environmental service affected, certainty and timing of the effects, and potential magnitude of economic consequences. We then described the nature of important eco- nomic effects and provided estimates of larger, more certain effects for which data were available. Largest economic effects were associated with costs to prevent damage, relocate, and replace infrastructure threatened by permafrost thaw, sea level rise, and coastal erosion. The costs to infrastructure were offset by a large projected reduction in space heating costs attributable to milder winters. Overall, we estimated that five relatively certain, large effects that could be readily quantified would impose an annual net cost of $340–$700 million, or 0.6%–1.3% of Alaska’s GDP. -

Alaska's Climate Change Policy Development

Alaska’s Climate Change Policy Development March 2021 Authored by: Abigail Steffen, Stephen Arturo Greenlaw, Maureen Biermann, and Amy Lauren Lovecraft Contact: [email protected] 1 LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT The Center of Arctic Policy Studies (CAPS) is located at Troth Yeddha', on the traditional homelands of the Tanana Dene People. ABOUT THE CENTER FOR ARCTIC POLICY STUDIES CAPS is an interdisciplinary, globally-informed group rooted in Alaska’s Interior at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) and housed within the International Arctic Research Center (IARC). We recognize the historical dimensions of policy contexts, the power of collaboration across disciplines and domains, and the use of integrative approaches towards problem-solving using evidence-based practices and a positive outlook toward the future of Alaska and the Arctic. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Abigail Steffen served as an Undergraduate Research Assistant at CAPS while completing bachelor’s degrees in Natural Resource Management and Foreign Languages and a minor in Global Climate Adaptation and Policy from UAF. Stephen Arturo Greenlaw served as Undergraduate Research Assistant at CAPS while completing his bachelor’s degree in Fisheries from UAF. He comes from generations of fisherfolk. During his time in Alaska, he worked with Pickled Willy’s, Tanana Chiefs Conference, the National Park Service, and the Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition. Maureen Biermann, MS, is Program Coordinator for CAPS. She has a master’s degree in Geography and is committed to supporting research on human and environmental change in the Arctic for the benefit of people and decision-makers at all scales. Amy Lauren Lovecraft, PhD, is the Director of CAPS and Professor of Political Science at the UAF. -

A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska Gerd Wendler University of Alaska, Fairbanks, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Natural Resources Natural Resources, School of 2009 A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska Gerd Wendler University of Alaska, Fairbanks, [email protected] Martha Shulski University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers Part of the Climate Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Meteorology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Other Environmental Sciences Commons Wendler, Gerd and Shulski, Martha, "A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska" (2009). Papers in Natural Resources. 563. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natrespapers/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Natural Resources, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Natural Resources by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ARCTIC VOL. 62, NO. 3 (SEPTEMBER 2009) P. 295-300 A Century of Climate Change for Fairbanks, Alaska GERD WENDLER1'2 and MARTHA SHULSKI1 (Received 16 June 2008; accepted in revised form 21 November 2008) ABSTRACT. Climatological observations are available for Fairbanks, Interior Alaska, for up to 100 years. This is a unique data set for Alaska, insofar as it is of relatively high quality and without major breaks. Applying the best linear fit, we conclude that the mean annual temperature rose from -3.6°C to -2.2°C over the century, an increase of 1.4°C (compared to 0.8°C worldwide). -

2018 Alaska Climate Summary

Alaska Climate Research Center Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Annual Report for 2018 prepared for The American Association of State Climatologists The Alaska Climate Research Center (ACRC) is part of the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks. Historically, the ACRC has shared tasks with the Alaska State Climate Center, and we are excited to report that both centers are currently in the process to merge. The main tasks and objectives of the Alaska State Climate Center have been renewed within the 2018 Alaska State Statutes via Title 14, Chapter 40, Section 085. Specific information can be found about this statute at http://www.legis.state.ak.us/basis/statutes.asp#14.40.085. Funding support for the ACRC comes from the Geophysical Institute and externally funded research projects. Key Personnel: Martin Stuefer, Director ACRC, Research Associate Professor Lea Hartl, Post Doctoral Researcher ACRC Jason Grimes, Research Technician ACRC Gerd Wendler, previous Director, ACRC, Professor Emeritus Blake Moore, Programmer Telayna Gordon, Research Technician Purpose: The purpose of the center is threefold: • Dissemination of climatological information and data. • Research on climate variability and climate change in Alaska and Polar Regions, and • Education and engagement with our stakeholders. Dissemination: For nearly three decades we have made climatological data available to the public, private, and government agencies, and to researchers around the world. Over the course of a year, winter is the busiest season for public inquiries to the Alaska Climate Research Center, probably due to the very cold temperatures (down to -40°F and colder) and ice fog, which makes driving difficult, if not dangerous. -

Alaska's Climate Change Policy Development

Alaska’s Climate Change Policy Development March 2021 Authored by: Abigail Steffen, Stephen Arturo Greenlaw, Maureen Biermann, and Amy Lauren Lovecraft Contact: [email protected] 1 LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT The Center of Arctic Policy Studies (CAPS) is located at Troth Yeddha', on the traditional homelands of the Tanana Dene People. ABOUT THE CENTER FOR ARCTIC POLICY STUDIES CAPS is an interdisciplinary, globally-informed group rooted in Alaska’s Interior at the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) and housed within the International Arctic Research Center (IARC). We recognize the historical dimensions of policy contexts, the power of collaboration across disciplines and domains, and the use of integrative approaches towards problem-solving using evidence-based practices and a positive outlook toward the future of Alaska and the Arctic. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Abigail Steffen served as an Undergraduate Research Assistant at CAPS while completing bachelor’s degrees in Natural Resource Management and Foreign Languages and a minor in Global Climate Adaptation and Policy from UAF. Stephen Arturo Greenlaw served as Undergraduate Research Assistant at CAPS while completing his bachelor’s degree in Fisheries from UAF. He comes from generations of fisherfolk. During his time in Alaska, he worked with Pickled Willy’s, Tanana Chiefs Conference, the National Park Service, and the Fairbanks Climate Action Coalition. Maureen Biermann, MS, is Program Coordinator for CAPS. She has a master’s degree in Geography and is committed to supporting research on human and environmental change in the Arctic for the benefit of people and decision-makers at all scales. Amy Lauren Lovecraft, PhD, is the Director of CAPS and Professor of Political Science at the UAF.