Obsessive Pursuit Final.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomberg Hunger Stalks My Father’S India Long After Starvation Banished by Mehul Srivastava • Bloomberg News

NEWSBloomberg Hunger Stalks My Father’s India Long After Starvation Banished By Mehul Srivastava • Bloomberg News October 23, 2012 – It was 1958, my father was still a child, and India was running out of food. That year’s wheat crop had slumped by 15 percent, the rice harvest by 12 percent, and prices in the markets were soaring. Far from his village in eastern India, ships laden with wheat were steaming toward the country, part of U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower’s plan to sell surplus grains, tobacco and dairy products to friendly countries. All India Radio gave daily updates on the convoys, and the army barricaded ports in Mumbai and Kolkata against the hungry crowds. “It was this very coarse, red wheat,” said Narsingh A villager sweeps the streets in Auar Village. Deo Mishra, a childhood friend of my father’s and Photographer: Sanjit Das/Bloomberg now a local politician in their home village. “We were told it was meant for American pigs,” said Mishra, stomachs; not enough to stay healthy. who, like my father, grew up listening to stories about More than five decades after those U.S. deliveries, the food shipments. “Back then, we weren’t any better I returned to the dusty, hot village of my father’s than American pigs. So we ate it. We ate it all and we childhood, hoping to understand why. begged for more.” In the arc of modern India’s elemental struggle to That year, and the hungry ones that followed, took feed its teeming people, my father’s childhood years their toll. -

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings Q1: Assembly elections are going to be held in Uttar Pradesh in the next few weeks. Will you vote in these elections? N (%) 1: No 239 3.7 2: Yes 6073 93.8 3: May be 107 1.7 8: Can't say 54 .8 Total 6473 100.0 Q2: The Election Commission in its verdict has allotted the cycle symbol to the Akhilesh Yadav faction, deeming it to be the real Samajwadi party. Do you believe that it was the right decision or wrong? N (%) 1: Right 3951 61.0 2: Wrong 677 10.5 8: Can't say 1846 28.5 Total 6473 100.0 Q3: If UP Assembly elections are held tomorrow, which party will you vote for? N (%) 01: Congress 204 3.1 02: BJP 1863 28.8 03: BSP 1490 23.0 05: RLD 124 1.9 06: Apna Dal 3 .0 08: Apna Dal (Anupriya Patel) 14 .2 09: Quami Ekta Dal 9 .1 11: Peace Party 54 .8 12: Mahan Dal 20 .3 13: CPI 66 1.0 14: CPI(M) 16 .3 17: RJD 5 .1 Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, CSDS Page 1 Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings N (%) 19: Shiv Sena 18 .3 21: AIMIM 25 .4 22: INLD 55 .8 23: LJP 13 .2 26: Lok Dal 17 .3 32: SP (Akhilesh Yadav)/SP 1972 30.5 56: SP (Mulayam Singh) 84 1.3 96: Independent 41 .6 97: Other parties 313 4.8 98: Can’t say/Did not tell 65 1.0 Total 6473 100.0 a: (If voted in Q3 ) On the day of voting will you vote for the same party which you voted now or your decision may change? N (%) Valid (%) Valid 1: Vote for the same party 4459 68.9 73.9 2: May change 800 12.4 13.3 8: Don't know 773 11.9 12.8 Total 6033 93.2 100.0 Missing 9: N.A. -

Sheikha Moza Serious Breach and fl Agrant Violations Structed and Kidnapped a Qatari fi Shing China’S President Xi Jinping Was of International Law

QATAR | Page 24 SPORT | Page 1 Qatar’s Adel leads T2 series aft er INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-9, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Second Aspire Kite REGION 9 BUSINESS 1-5, 17-20 solid fi nish Festival attracted 25,360.00 8,303.34 62.04 ARAB WORLD 9, 10 CLASSIFIED 6-16 +439.00 -62.77 +1.92 INTERNATIONAL 11-21 SPORTS 1-8 over 40,000 visitors in Dubai +1.76% -0.75% +3.19% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 SUNDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 10754 March 11, 2018 Jumada Il 23, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals FM in Sudan meeting Qatar informs In brief UN of airspace QATAR | Reaction violations by Qatar slams withdrawal of Jerusalem identity Qatar strongly condemned the Israeli Knesset’s approval of a law UAE, Bahrain authorising the interior minister to withdraw the Jerusalem identity atar has informed the UN Secu- in the region and without regard to Qa- from the Palestinians. In a statement rity Council and the UN Secre- tar’s security and stability.” yesterday, the Foreign Ministry Qtary-General of three violations The Government of Qatar has called described the move as unethical and of Qatar’s airspace by the United Arab upon the Security Council and the completely disregarding international Emirates (UAE) and the Kingdom of United Nations to take the necessary law, international humanitarian law Bahrain. measures under the Charter of the and UN conventions. The statement The message was handed over by HE United Nations to maintain interna- called on the international community the Permanent Representative of Qa- tional peace and security. -

From the Editor's Desk *****

9 July 2014 | Vol. 5, № 24. From the Editor’s Desk Dear FDI supporters, Welcome to the Strategic Weekly al-Barrak. While further demonstrations Analysis. seem likely, even after al-Barrak’s release, the record level of public expenditure in We open this week’s edition with a the latest Budget should help to counter discussion of the new star-rated healthy at least some grievances. food rating system, to be introduced to Australian consumers next month. This week’s edition concludes with an assessment of the promise made by both Next, we turn to Pakistan and analyse the candidates in Indonesia’s presidential importance to its economy of its booming election to extend the compulsory length textile industry and mango exports and of schooling from nine to 12 years. If also the interest that it holds for investors implemented, the measure will be an from China and the United States. important step in improving the country’s Our next article looks at India and education system. highlights the importance of the National I trust you will enjoy this edition of the Food Security Act – and the difficulties Strategic Weekly Analysis. being experienced in its implementation. Major General John Hartley AO (Retd) Moving next to the Middle East, we Institute Director and CEO evaluate the possibility of widespread Future Directions International civic unrest, in Kuwait, following the detention of opposition leader Musallam ***** Nutrition Rating System Given Green Light for Australian Food Packaging A voluntary, five-star, healthy food rating system will begin in Australia and New Zealand in August, following a public education campaign. -

Dalit Feminism Versus Deadly Feudalism. Whatever the Validity of the POTA Cases Garh

STATES ■ UTTAR PRADESH OUTDOING THE OUTLAW SHARAD SAXENA Dalit feminism versus deadly feudalism. Whatever the validity of the POTA cases garh. The father’s Raj Mahal (regal palace) in Bhadri and the son’s house in against Raja Bhaiya’s clan, to Mayawati’s voters they signal social revolution. Behti, near Kunda town, have been raided for the first time in living mem- ory. Weapons, including AK-56 assault ■ by Subhash MISHRA rifles, have been found. Says District TTAR PRADESH IS OFTEN Magistrate Mohammed Mustafa, “We mocked for being Ulta Pradesh have also sought the army’s help to (topsy-turvy province). Now it excavate the Raj Mahal.” has upturned traditional Among the other “treasures” hierarchies of caste oppres- unearthed from the Raj Mahal is a U SETTLING SCORES: Mayawati; the skeleton sion. In the benign reign of Chief Min- human skeleton. Fished out of a pond, ister Mayawati (BSP), a Dalit-led regime the police say it is of one Santosh fished out of a pond in Raj Mahal (right) is making life miserable for a Rajput Mishra, a local who disappeared in patriarch and his son. 2001. Also in police custody is the “eco- charisma, family loyalty and patronage. It began in October last year, when nomic empire” of the Bhadri estate. The He is at once abhorred and adulated. Raghuraj Pratap Singh or Raja Bhaiya, district administration has seized 33 The arrest of Udai Pratap has alarm- 33, independent MLA from Kunda, liquor shops. The legal owners of these ed the Rajput community. From Amar Pratapgarh district, was arrested for vends, it says, are proxies for Raja Singh, general secretary, Samajwadi allegedly threatening a pro-Mayawati Bhaiya and his father. -

SUPREME COURT of INDIA Page 1 of 18

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 1 of 18 CASE NO.: Writ Petition (crl.) 132-134 of 2003 PETITIONER: S.K. Shukla & Ors RESPONDENT: State of U.P. & Ors. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 10/11/2005 BENCH: B.N. Agrawal & A.K. Mathur JUDGMENT: J U D G M E N T (with SLP(Crl) No. 1521/2004, T.P.(Crl) Nos. 82-84/2004 & Crl.A. 1511/2005 @ SLP (Crl) No. 5609/2004) A.K. MATHUR, J. All these cases are inter-related and common arguments were raised, therefore, they are disposed of by this common order. Writ Petition Nos 132-134/2003 under Article 32 of the Constitution of India is directed against the withdrawal of the POTA order by the State Government dated 29th August 2003 against accused Udai Pratap Singh, Raghuraj Pratap Singh @ Raja Bhaiya & Akshay Pratap Singh @ Gapalji. The Union of India was also permitted to be impleaded as a party-respondent. In SLP (Crl) 5609 of 2004, the petitioner has challenged the order passed by the POTA Review Committee dated 30.4.2004 under Section 60 of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (15 of 2002) (hereinafter referred to as 'the POTA'). Leave granted. In SLP (Crl) 1521 of 2004, the High Court order dated 24.2.2004 was challenged whereby accused Akshay Pratap Singh @ Gopalji was granted bail in case No.10 of 2003, under Section 3/4 of POTA, Police Station Kunda, District Pratapgarh, U.P. on his furnishing a personal bond for Rs.1,00,000/- with two sureties each in the like amount to the satisfaction of the Special Judge, designated court, Kanpur. -

7SUNDC COL 07R2.QXD (Page 1)

œND‰‹‰†‰KœND‰‹‰†‰œND‰‹‰†‰MœND‰‹‰†‰C INDIA SUNDAY TIMES OF INDIA New Delhi, September 7, 2003 7 Mulayam inducts six into BJP considers ‘Who’s a criminal? giving Mamata I was simply a another chance ministry as 37 desert BSP TIMES NEWS NETWORK By Arvind Singh Bisht 181 after the addition of 37 New Delhi: A high-level TIMES NEWS NETWORK BSP MLAs — is likely to meeting at the PM’s res- political opponent’ touch 187, as the breakaway idence on Saturday Lucknow: Six MLAs were BSP group has claimed the evening discussed the sworn in as members of the support of six more MLAs. oom No. Two in Shayma Prasad Mukherjee Hos- Mulayam Singh Yadav min- possibility of a few pital smells like a florist’s shop. Jubilant men Apart from this, Mulayam changes in the Vajpayee istry here late on Saturday already enjoys the support of R guard it’s entry as UP’s bigwigs flit in and out. night. The six are Shivpal ministry as well as the Basking in the adulation is Raghuraj Pratap Singh, the the Congress (16), RLD (14), impact of the political Singh Yadav and Azam Khan RKP (4), two MLAs each of enfant terrible of the Kunda royal family. UP’s first of the SP, Kokab Hamid and changes in Uttar POTA prisoner is still ‘‘trying hard to get used to crowds the CPM and the Loktantrik Pradesh. Sources said Anuradha Choudhary of the Congress and six of the splin- after a solitary confinement of six months’’. RLD and Rajvir Singh and the ministerial changes Confined as he is to hospital bed due to a spinal disor- tered groups, besides 13 Inde- were likely in the first Kusum Rai of the RKP. -

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings

Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings Q1: Assembly elections are going to be held in Uttar Pradesh in the next few weeks. Will you vote in these elections? N (%) 1: No 186 2.9 2: Yes 6124 94.5 3: May be 109 1.7 8: Can't say 61 .9 Total 6481 100.0 Q2: The Election Commission in its verdict has allotted the cycle symbol to the Akhilesh Yadav faction, deeming it to be the real Samajwadi party. Do you believe that it was the right decision or wrong? N (%) 1: Right 3972 61.3 2: Wrong 615 9.5 8: Can't say 1894 29.2 Total 6481 100.0 Q3: If UP Assembly elections are held tomorrow, which party will you vote for? N (%) 01: Congress 253 3.9 02: BJP 1826 28.2 03: BSP 1196 18.5 05: RLD 61 .9 06: Apna Dal 3 .0 08: Apna Dal (Anupriya Patel) 14 .2 09: Quami Ekta Dal 11 .2 11: Peace Party 2 .0 12: Mahan Dal 1 .0 13: CPI 3 .0 14: CPI(M) 1 .0 17: RJD 3 .0 Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, CSDS Page 1 Uttar Pradesh Tracker Poll January 2017-Findings N (%) 19: Shiv Sena 1 .0 21: AIMIM 1 .0 22: INLD 2 .0 23: LJP 0 .0 26: Lok Dal 1 .0 32: SP (Akhilesh Yadav)/SP 2446 37.7 56: SP (Mulayam Singh) 104 1.6 96: Independent 2 .0 97: Other parties 12 .2 98: Can’t say/Did not tell 542 8.4 Total 6481 100.0 a: (If voted in Q3 ) On the day of voting will you vote for the same party which you voted now or your decision may change? N (%) Valid (%) Valid 1: Vote for the same party 4588 70.8 76.4 2: May change 643 9.9 10.7 8: Don't know 773 11.9 12.9 Total 6004 92.6 100.0 Missing 9: N.A. -

50 UAE, Bahrain Troops Killed in Yemen Clashes

SUBSCRIPTION SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2015 THULQADA 21, 1436 AH No: 16631 MP calls to shut Drowned Syrian Asian football Iran embassy boys buried in fans cringe over after statement3 town they7 fled record48 scores 50 UAE, Bahrain troops killed in Yemen clashes Min 30º 150 Fils Black day for coalition • Amir sends condolences Max 42º ABU DHABI: The UAE said 45 of its troops were killed in Yemen and Bahrain said it lost five soldiers yesterday, the deadliest day for a Saudi-led coalition battling Yemeni Shiite rebels. The Yemeni government said an “accidental explosion” at an arms depot at a military base in the eastern province of Marib killed the Emiratis, but the Houthi rebels said their fighters launched a rocket attack that caused the blast. Coalition ally Bahrain said five of its soldiers were killed in southern Saudi Arabia where they had been posted to help defend the border with war- wracked Yemen, but it did not give a precise location. However, Yemen’s exiled presidency said the Bahrainis died in the same blast that killed the Emirati forces. Twenty three soldiers wounded in the incident died of their injuries, raising the toll from an initial 22, the Emirati state news agency WAM reported. The UAE armed forces did not dis- close the circumstances of what was its highest casualty toll of the six-month-old air war. But Anwar Gargash, UAE minister of state for foreign affairs, said on Twitter yesterday that “a rocket and an explosion at a weapons cache targeted the martyrs”. HH the Amir of Kuwait Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al- Sabah yesterday sent a cable of condolences to UAE President Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al-Nahyan on the martyrdom of the UAE soldiers. -

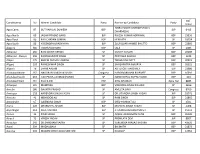

Constituency No Winner Candidate Party Runner-Up Candidate Party Votes GIRRAJ SINGH DHARMESH (G.S

Diff. Constituency No Winner Candidate Party Runner-up Candidate Party Votes GIRRAJ SINGH DHARMESH (G.S. Agra Cantt. 87 GUTIYARI LAL DUWESH BSP BJP 6415 DHARMESH) Agra North 89 JAGAN PRASAD GARG BJP RAJESH KUMAR AGRAWAL BSP 23356 Agra Rural 90 KALI CHARAN SUMAN BSP HEMLATA SP 18754 Agra South 88 YOGENDRA UPADHYAYA BJP ZULFIQUAR AHMED BHUTTO BSP 22960 Ajagara 385 TRIBHUVAN RAM BSP LALJI SP 2083 Akbarpur 281 RAM MURTI VERMA SP SANJAY KUMAR BSP 26286 Akbarpur - Raniya 206 RAMSWAROOP SINGH SP PRATIBHA SHUKLA BSP 1243 Alapur 279 BHEEM PRASAD SONKAR SP TRIBHUVAN DATT BSP 30023 Aliganj 103 RAMESHWAR SINGH SP SANGHMITRA MAURYA BSP 26021 Aligarh 76 ZAFAR AALAM SP ASHUTOSH VARSHNEY BJP 23086 Allahabad North 262 ANUGRAH NARAYAN SINGH Congress HARSHVARDHAN BAJPAYEE BSP 16092 Allahabad South 263 HAJI PARVEJ AHMAD (TANKI) SP NAND GOPAL GUPTA NANDI BSP 414 Allahabad West 261 POOJA PAL BSP ATIQ AHAMAD Apna Dal 8885 Amanpur 101 MAMTESH BSP VIRENDRA SINGH SOLANKI SP 3656 Amethi 186 GAYATRI PRASAD SP AMEETA SINH Congress 8760 Amritpur 193 NARENDRA SINGH YADAV SP DR. JITANDRA SINGH YADAV JKP 18971 Amroha 41 MEHBOOB ALI SP RAM SINGH BJP 21805 Anupshahr 67 GAJENDRA SINGH BSP SYED HIMAYAT ALI SP 3501 Aonla 126 DHARM PAL SINGH BJP MAHIPAL SINGH YADAV SP 4408 Arya Nagar 214 SALIL VISHNOI BJP JITENDRA BAHADUR SINGH SP 15411 Asmoli 32 PINKI SINGH SP AQEEL UR REHMAN KHAN BSP 26389 Atrauli 73 VIRESH YADAV SP PREMLATA DEVI JKP 8867 Atrauliya 343 DR.SANGRAM YADAV SP SURENDRA PRASAD MISHRA BSP 43620 Aurai 394 MADHUBALA SP BAIJNATH BSP 21873 Auraiya 204 MADAN SINGH ALIAS -

S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav C/O S

PERSONAL ASSISTANT EXAMINATION-2013 List of Eligible Candidates Date of Examination will be intimated later on. S. No. Name (Mr./Ms) Father's/Husband's Name Correspondence Address Date of Birth C/o suresh Kumar, H.NO. 61, 1 Ms. Vijayta Raghav Mr. Manmohan Raghav Village- Motibagh, Nr. 8.09.1985 Nanakpura, N.D. 21. DB-75 A, DDA Flats, Hari 2 Ms. Shalini Sharma Mr. Gaurav Rana 5.11.1984 Nagar, New Delhi -64 D-8/184, East Gokal Pur, 3 Mr. Deepak Kumar Mr. Atal Singh 2.04.1985 Shahdara North East Delhi-94. WZ-303, Sant Garh, St. No. 18, 4 Ms. Surinder Kaur Mr. Daljeet Singh Ground Floor, M.B.S. Nagar, 15.06.1987 Tilak Nagar, New Delhi -18. E-196, Sector-23, Sanjay Nagar, 5 Ms. Jyoti Mr. Rajesh Kumar 18.02.1988 Ghaziabad, UP - 201002. 57-P, DIZ Area, Gole Market 6 Ms. Richa Bajaj Mr. Kamal Bajaj (Raja Bazar), Sec.-4, New Delhi- 5.05.1982 01. H.No. 50, Krishan Kunj colony, 7 Ms. Neetu Kansal Mr. Manish Kansal 18.04.1987 Laxmi Nagar, Delhi - 92. CBI Academy, Hapur Road, 8 Ms. Bharati Sharma Mr. Kamal Prakash Sharma Kamla Nehru Nagar, 22.02.1990 Ghaziabad, U.P.- 201002. H.No. 6612, Radhey Puri, Ext. 9 Ms. Rekha Mahour Mr. Dinesh Kumar 2.07.1989 No. 2, Krishna Nagar, Delhi -51. A/561, Madi Pur Colony, New 10 Ms. Madhu Bala Lt. Mr. Madan Lal 1.11.1986 Delhi - 63. D-106, Gali No. 5, Laxmi Nagar, 11 Ms. Premlata Mr. Dayaram Sharma 28.7.1990 New Delhi-92. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information

The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUMELVIII NO.2 JUNE2012 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. 24, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi-2 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor : T.K.Viswanathan Secretary-General Lok Sabha AssociateEditors : P.K.Misra Joint Secretary Lok Sabha Secretariat Kalpana Sharma Director Lok Sabha Secretariat AssistantEditors : PulinB.Bhutia Additional Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Parama Chatterjee Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat Sanjeev Sachdeva Joint Director Lok Sabha Secretariat © Lok Sabha Secretariat, New Delhi THE JOURNAL OF PARLIAMENTARY INFORMATION VOLUMELVIII NO.2 JUNE2012 CONTENTS PAGE EDITORIAL NOTE 151 ADDRESSES Address by the President to the Parliament 12March2012 152 PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES ConferencesandSymposia 169 BirthAnniversariesofNationalLeaders 170 ExchangeofParliamentaryDelegations 171 BureauofParliamentaryStudies andTraining 173 PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS 176 SESSIONAL REVIEW LokSabha 188 StateLegislatures 208 RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST 213 APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the TenthSessionoftheFifteenthLokSabha 219 II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 225th SessionoftheRajyaSabha 223 III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories duringthe period1Januaryto31March 2012 224 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and Assented to by the President during the period 1Januaryto31March2012 230 (iv) iv The Journal of Parliamentary Information V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during theperiod1Januaryto31March2012 231 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1Januaryto31March2012 240 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and Legislatures oftheStatesandtheUnionTerritories 246 Jai Mata Di final EDITORIAL NOTE The Constitution of India provides for an Address by the President to either House of Parliament or both the Houses assembled together.