Must Jewish Medical Ethics Regarding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Technology in Germany and the United States: an Essay in Comparative Law and Bioethics

ROBERTSON - REVISED FINAL PRINT VERSION.DOC 12/02/04 6:55 PM Reproductive Technology in Germany and the United States: An Essay in Comparative Law and Bioethics * JOHN A. ROBERTSON The development of assisted reproductive and genetic screening technologies has produced intense ethical, legal, and policy conflicts in many countries. This Article surveys the German and U.S. experience with abortion, assisted reproduction, embryonic stem cell research, therapeutic cloning, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. This exercise in comparative bioethics shows that although there is a wide degree of overlap in many areas, important policy differences, especially over embryo and fetal status, directly affect infertile and at-risk couples. This Article analyzes those differences and their likely impact on future reception of biotechnological innovation in each country. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................190 I. THE IMPORTANCE OF CONTEXT.............................................193 II. GERMAN PROTECTION OF FETUSES AND EMBRYOS ...............195 III. ABORTION .............................................................................196 IV. ASSISTED REPRODUCTION .....................................................202 A. Embryo Protection and IVF Success Rates................204 B. Reducing Multiple Gestations ....................................207 C. Gamete Donors and Surrogates .................................209 V. EMBRYONIC STEM CELL RESEARCH......................................211 -

Kol Hamishtakker

Kol Hamishtakker Ingredients Kol Hamishtakker Volume III, Issue 5 February 27, 2010 The Student Thought Magazine of the Yeshiva 14 Adar 5770 University Student body Paul the Apostle 3 Qrum Hamevaser: The Jewish Thought Magazine of the Qrum, by the Qrum, and for the Qrum Staph Dover Emes 4 Reexamining the Halakhot of Maharat-hood Editors-in-Chief The Vatikin (in Italy) 4 The End of an Era Sarit “Mashiah” Bendavid Shaul “The Enforcer” Seidler-Feller Ilana Basya “Tree Pile” 5 Cherem Against G-Chat Weitzentraegger Gadish Associate Editors Ilana “Good Old Gad” Gadish Some Irresponsible Feminist 7 A Short Proposal for Female Rabbis Shlomo “Yam shel Edmond” Zuckier (Pseudonym: Stephanie Greenberg) Censorship Committee Jaded Narrative 7 How to Solve the Problem of Shomer R’ M. Joel Negi’ah and Enjoy Life Better R’ Eli Baruch Shulman R’ Mayer Twersky Nathaniel Jaret 8 The Shiddukh Crisis Reconsidered: A ‘Plu- ral’istic Approach Layout Editor Menachem “Still Here” Spira Alex Luxenberg 9 Anu Ratzim, ve-Hem Shkotzim: Keeping with Menachem Butler Copy Editor Benjamin “Editor, I Barely Even Know Her!” Abramowitz Sheketah Akh Katlanit 11 New Dead Sea Sect Found Editors Emeritus [Denied Tenure (Due to Madoff)] Alex Luxenberg 13 OH MY G-DISH!: An Interview with Kol R’ Yona Reiss Hamevaser Associate Editor Ilana Gadish Alex Sonnenwirth-Ozar Friedrich Wilhelm Benjamin 13 Critical Studies: The Authorship of the Staph Writers von Rosenzweig “Documentary Hypothesis” Wikipedia Arti- A, J, P, E, D, and R Berkovitz cle Chaya “Peri Ets Hadar” Citrin Rabbi Shalom Carmy 14 Torah u-Media: A Survey of Stories True, Jake “Gush Guy” Friedman Historical, and Carmesian Nicole “Home of the Olympics” Grubner Nate “The Negi’ah Guy” Jaret Chaya Citrin 15 Kol Hamevater: A New Jewish Thought Ori “O.K.” Kanefsky Magazine of the Yeshiva University Student Alex “Grand Duchy of” Luxenberg Body Emmanuel “Flanders” Sanders Yossi “Chuent” Steinberger Noam Friedman 15 CJF Winter Missions Focus On Repairing Jonathan “’Lil ‘Ling” Zirling the World Disgraced Former Staph Writers Dr. -

AEC-Brochure-Fall-2018-WEB Revised 180922

ADULT EDUCATION FALL 2018 Jewish Community of Amherst 742 Main Street, Amherst, MA 01002 413.256.0160 ~ www. jcamherst.org JCA adult education programs reflect religious, secular, practical, and cultural aspects of Judaism. We hope that you will find something that appeals to you. Register and contribute online at http://bit.ly/jca1819Faec If you prefer to register by mail and contribute via check, please print the registration form at the end of this brochure or pick one up in the JCA lobby. FALL 2018 PROGRAMS AT A GLANCE Lunch anD Learn Israeli Film Series Rabbi Benjamin Weiner Sundays • 2 – 5 pm Wednesdays • 12:15 – 1:15 pm October 21: The Band’s Visit December 9: Zero Motivation SepharDic Civilization Ilan Stavans Greatest Hits of the TalmuD September 25; October 2, 9 Rabbi Devorah Jacobson Tuesdays • 7 – 9 pm October 31; November 7, 14, 28; December 5, 12 Wednesdays • 6:30 – 7:45 pm Prayerbook Hebrew Literacy Janis Levy Creating a Jewish Home October 15 – December 3 facilitated by Melanie Lewis Mondays • 7:00 – 8:30 pm November 4, December 9 Sundays • 10:45 – 11:45 am Meet Me at the Well Book ReaDing Jane Yolen and Barbara Diamond Goldin “A Reason to Remember” Exhibition Tour Sunday, October 14 • 11 am – 12:30 pm Deborah Roth-Howe November 7 • 4 – 5:30 pm • JCA Kesher only Israeli Dancing Randi Stein OrthoDox Feminism October 23, 30; November 13, 20 A conversation with Rabbi Lila Kagedan Tuesdays • 7:00 – 8:30 pm Sunday, December 2 • 1 – 3 pm If you would like to suggest future programming, please contact a member of the Adult Education Committee: Barbara Burkart (chair), Jane Brodwyn, David Glassberg, Diane Gnepp, Phyllis Herda, Jonathan Lewis, Melanie Lewis, Ruth Smith, Linda Terry, Boris Wolfson, Janis Wolkenbreit, Rabbi Benjamin Weiner (ex officio) Lunch and Learn Rabbi Benjamin Weiner Wednesdays • 12:15 – 1:15 pm Now in its seventh year, Lunch and Learn continues its investigation of Halakha, or the tradition of Jewish law. -

KEMRI Bioethics Review 4

JulyOctober- - September December 20152015 KEMRI Bioethics Review Volume V -Issue 4 2015 Google Image Reproductive Health Ethics October- December 2015 Editor in Chief: Contents Prof Elizabeth Bukusi Editors 1. Letter from the Chief Editor pg 3 Dr Serah Gitome Ms Everlyne Ombati Production and Design 2. A Word from the Director KEMRI pg 4 Timothy Kipkosgei 3 Background and considerations for ethical For questions and use of assisted reproduction technologies in queries write Kenyan social environment pg 5 to: The KEMRI Bioethics Review 4. Reproductive Health and HIV-Ethical Dilemmas In Discordant Couples Interven- KEMRI-SERU P.O. Box 54840-00200 tions pg 9 Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] 5. The Childless couple: At what cost should childlessness be remedied? pg 12 6. Multipurpose Prevention Technologies As Seen From a Bowl of Salad Combo pg 15 7. Case challenge pg 17 KEMRI Bioethics Review Newsletter is an iniative of the ADILI Task Force with full support of KEMRI. The newsletter is published every 3 months and hosted on the KEMRI website. We publish articles written by KEMRI researchers and other contributors from all over Kenya. The scope of articles ranges from ethical issues on: BIOMEDICAL SCIENCE, HEALTHCARE, TECHNOLOGY, LAW , RELIGION AND POLICY. The chief editor encourages submisssion of articles as a way of creating awareness and discussions on bioethics please write to [email protected] 2 Volume V Issue 4 October- December 2015 Letter from the Chief Editor Prof Elizabeth Anne Bukusi, MBChB, M.Med (ObGyn), MPH, PhD , PGD(Research Ethics). MBE (Bioethics) , CIP (Certified IRB Professional). Chief Research Officer and Deputy Director (Research and Train- ing) KEMRI Welcome to this issue of KEMRI Bioethics Review focusing on Reproductive Health Ethics. -

Artificial Insemination, Egg Donation, and Adoption

EH 1:3.1994 ARTIFICIAL INSEMINIATION, EGG DoNATION AND ADoPTION Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff This paper wa.s approred by the CJLS on /Harch 16, 199-1, by a vote (!f'trventy one inf(rnJr and one abstention (21-0-1). K1ting infiwor: Rabbis K1tssel Abel""~ Bm Lion Bergmwz, Stanley Bmmniclr, Hlliot N. Dorff; Samuel Fmint, Jl}TOn S. Cellrt; Arnold M. Goodman, Susan Crossman, Jan Caryl Kaufman, Judah Kogen, vernon H. Kurtz, Aaron T.. :lfaclder, Herbert i\Iandl, Uonel F:. Moses, Paul Plotkin, Mayer Rabinou,itz, Joel F:. Rembaum, Chaim A. Rogoff; Joel Roth, Gerald Skolnih and Cordon Tucher. AlJstaining: Rabbi Reuren Kimelman. 1he Committee 011 .lnuish L(Lw and Standards qf the Rabbinical As:wmbly provides f};ztidance in matters (!f halakhnh for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the (Wtlwri~yfor the interpretation nnd application r~f all mntters of' halaklwh. An infertile Jewish couple has asked the following questions: Which, if any, of the new developments in reproductive technology does Jewish law require us to try? \'\Thich rnay we try? Which, if any, does Jewish law forbid us to try? If we are not able to conceive, how does Jewish law view adoption? TIH:s<: questions can best he trcat<:d hy dividing those issues that apply to the couple from those that apply to potential donors of sperm or eggs, and by separately delineating the sta tus in Jewish law of the various techniques currently available. For the Couple May an infertile Jewish couple use any or all of the following methods to procreate: (1) arti ficial insemination -

The Bayit BULLETIN

ה׳ד׳ ׳ב׳ ׳ א׳ד׳ט׳ט׳ת׳ד׳ת׳ ׳ ׳ ד׳ר׳ב׳ד׳ ׳ב׳ד׳ ׳ ~ Hebrew Institute of Riverdale The Bayit BULLETIN June 5 - 12, 2015 18 - 25 Sivan 5775 Hebrew Institute of Riverdale - The Bayit Mazal Tov To: 3700 Henry Hudson Parkway Luba & David Teten on the birth of a son. To big sisters Leona, Peri and Sigal. Bronx, NY 10463 Rabbinic Intern Daniel Silverstein on being included in the Jewish Week’s 36 Under 36 most www.thebayit.org influential young Jewish Leaders for the year 2015. E-mail: [email protected] This Shabbat @ The Bayit Phone: 718-796-4730 Fax: 718-884-3206 LAST TENT CONNECTIONS AT ABRAHAM & SARAH’S TENT: More info on page 4. R’ Avi Weiss: [email protected]/ x102 KIDDUSH THIS SHABBAT IS SPONSORED BY THE TETEN FAMILY: In honor of R’ Sara Hurwitz: [email protected]/ x107 our new baby boy (Brit on Tuesday morning); Luba’s upcoming June birthday; and the great R’ Steven Exler: [email protected]/ x108 community helping us out with our new addition, especially Aimee & Jonathan Baron; Kathy R’ Ari Hart: [email protected]/ x124 Goldstein & Ahron Rosenfeld; Debra Kobrin & Daniel Levy; Shoshana Bulow; Elana & Bradley Saenger and Frederique & Andy Small. Kiddush SEUDA SHLISHIT: Join us after Mincha for Seuda Shlishit in the Social Hall. Sponsored by the Teten family. The Summer Celebration Kiddush This Sunday, June 7th @ The Bayit will be 6/20/2015. KAVVANAH TEFILLAH | 9:00am: An hour of slower tefillah with Rav Steven To sponsor visit www.thebayit.org/celebration including meditation & song. -

Religious Aspects of Assisted Reproduction

FACTS VIEWS VIS OBGYN, 2016, 8 (1): 33-48 Review Religious aspects of assisted reproduction H.N. SALLAM1,2, N.H. SALLAM2 Department of 1Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Alexandria Fertility and 2IVF Center, Alexandria, Egypt. Correspondence at: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Human response to new developments regarding birth, death, marriage and divorce is largely shaped by religious beliefs. When assisted reproduction was introduced into medical practice in the last quarter of the twentieth century, it was fiercely attacked by some religious groups and highly welcomed by others. Today, assisted reproduction is accepted in nearly all its forms by Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism, although most Orthodox Jews refuse third party involvement. On the contrary assisted reproduction is totally unacceptable to Roman Catholicism, while Protestants, Anglicans, Coptic Christians and Sunni Muslims accept most of its forms, which do not involve gamete or embryo donation. Orthodox Christians are less strict than Catholic Christians but still refuse third party involvement. Interestingly, in contrast to Sunni Islam, Shi’a Islam accepts gamete donation and has made provisions to institutionalize it. Chinese culture is strongly influenced by Confucianism, which accepts all forms of assisted reproduction that do not involve third parties. Other communities follow the law of the land, which is usually dictated by the religious group(s) that make(s) the majority of that specific community. The debate will certainly continue as long as new developments arise in the ever-evolving field of assisted reproduction. Key words: Assisted reproduction, Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, ICSI, IVF, Judaism, religion, religious aspects. Introduction birth, death, marriage or divorce. -

Outcome of Assisted Reproductive Technology in Men with Treated and Untreated Varicocele: Systematic Male Fertility Review and Meta‑Analysis

Asian Journal of Andrology (2016) 18, 254–258 © 2016 AJA, SIMM & SJTU. All rights reserved 1008-682X www.asiaandro.com; www.ajandrology.com Open Access INVITED REVIEW Outcome of assisted reproductive technology in men with treated and untreated varicocele: systematic Male Fertility review and meta‑analysis Sandro C Esteves1, Matheus Roque2, Ashok Agarwal3 Varicocele affects approximately 35%–40% of men presenting for an infertility evaluation. There is fair evidence indicating that surgical repair of clinical varicocele improves semen parameters, decreases seminal oxidative stress and sperm DNA fragmentation, and increases the chances of natural conception. However, it is unclear whether performing varicocelectomy in men with clinical varicocele prior to assisted reproductive technology (ART) improve treatment outcomes. The objective of this study was to evaluate the role of varicocelectomy on ART pregnancy outcomes in nonazoospermic infertile men with clinical varicocele. An electronic search was performed to collect all evidence that fitted our eligibility criteria using the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases until April 2015. Four retrospective studies were included, all of which involved intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), and accounted for 870 cycles (438 subjected to ICSI with prior varicocelectomy, and 432 without prior varicocelectomy). There was a significant increase in the clinical pregnancy rates (OR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.19–2.12, I 2 = 25%) and live birth rates (OR = 2.17, 95% CI: 1.55–3.06, I 2 = 0%) in the varicocelectomy group compared to the group subjected to ICSI without previous varicocelectomy. Our results indicate that performing varicocelectomy in patients with clinical varicocele prior to ICSI is associated with improved pregnancy outcomes. -

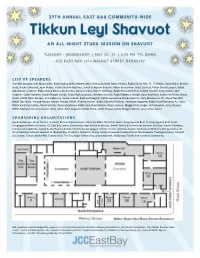

2017 Tikkun Program

LIST OF SPEAKERS Daniella Aboody, Joel Abramovitz, Rabbi Adina Allen, Robert Alter, Deena Aranoff, Barry Barkan, Rabbi Yanky Bell, Dr. Zvi Bellin, David Biale, Rachel Biale, Rachel Binstock, Joan Blades, Rabbi Shalom Bochner, Jonah Sampson Boyarin, Robin Braverman, Reba Connell, Rabbi David Cooper, Rabbi Menachem Creditor, Rabbi Diane Elliot, Julie Emden, Danny Farkas, Ron H. Feldman, Rabbi Yehudah Ferris, Estelle Frankel, Zelig Golden, Dor Haberer, Ophir Haberer, Rabbi Margie Jacobs, Rabbi Burt Jacobson, Ameena Jandali, Rabbi Rebecca Joseph, Ilana Kaufman, Rabbi Yoel Kahn, Binya Koatz, Rabbi Dean Kertesz, Arik Labowitz, Susan Lubeck, Raphael Magarik, Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin, Judy Massarano, Dr. David Neufeld, Rabbi Dev Noily, Amanda Nube, Martin Potrop, MSW, Andrew Ramer, Rabbi Dorothy Richman, Nehama Rogozen, Rabbi Yosef Romano, Avi Rose, Rabbi SaraLeya Schley, David Schiller, Naomi Seidman, Rabbi Sara Shendelman, Noam Sienna, Maggid Jhos Singer, Idit Solomon, Jerry Strauss, MSW, Maharat Victoria Sutton, Amy Tobin, Ariel Vegosen, Rabbi Peretz Wolf-Prusan, Rabbi Bridget Wynne, and Tamar Zaken SPONSORING ORGANIZATIONS Aquarian Minyan, Bend The Arc: A Jewish Partnership for Justice, Berkeley Hillel, Chochmat HaLev, Congregation Beth El, Congregation Beth Israel, Congregation Netivot Shalom, JCC East Bay, Jewish Community High School of the Bay, Jewish Family & Community Services East Bay, Jewish Gateways, Jewish LearningWorks, Jewish Studio Project, Kehilla Community Synagogue, Keshet, Kevah, Lehrhaus Judaica, Midrasha in Berkeley, -

Excerpt from Turning Points in Jewish History by Marc Rosenstein (The Jewish

Excerpt from Turning Points in Jewish History by Marc Rosenstein (The Jewish Publication Society, July 2018) The 50% of the Jewish Nation Almost Completely Unmentioned in Jewish History For the vast majority of Jewish history, the 50% of the Jewish nation who are of the female gender are almost completely unmentioned. This glaring omission can be attributed to two factors: 1) Even being a “people that dwells apart,” the Jews have been influenced by their gentile environment in every age. For most of its history, human society has been patriarchal….and by and large Jewish life has reflected the male-dominated culture of surrounding societies. 2) Men also oversaw the recording and transmitting of information about history and social norms. Thus, regardless of women’s actual roles in life and leadership, the documents we have from and about the past were written by men, about men, and for men. The extent of women’s contributions may have been lost or suppressed along the way…. A number of Jewish women are often mentioned to exemplify women’s important roles in various periods. However, the list [here] is short, suggesting these are the exceptions that prove the rule: • The Matriarchs (Genesis 12-35). Sarah, Rebekah, Rachel, and Leah each played an important role in steering the historical drama of the first three Israelite generations; both Sarah and Rebekah, for example, upended the established patriarchal system by causing the younger son to be favored over the first-born in carrying the family spiritual inheritance (Genesis 21 and 27 respectively). • The Hebrew midwives, and then Moses’ mother and sister and Pharaoh’s daughter, outsmarted Pharaoh’s decree to kill all Israelite male babies, thereby saving Moses’ life and playing a pivotal role in the redemption story (Exodus 1-2). -

Influence of Placental Abnormalities and Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension in Prematurity Associated with Various Assisted Reproduc

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Influence of Placental Abnormalities and Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension in Prematurity Associated with Various Assisted Reproductive Technology Techniques Judy E. Stern 1,* , Chia-ling Liu 2 , Sunah S. Hwang 3, Dmitry Dukhovny 4 , Leslie V. Farland 5, Hafsatou Diop 6, Charles C. Coddington 7 and Howard Cabral 8 1 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Lebanon, NH 03756, USA 2 Bureau of Family Health and Nutrition, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Boston, MA 02108, USA; [email protected] 3 Section of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO 80045, USA; [email protected] 4 Division of Neonatology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR 97239, USA; [email protected] 5 Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85724, USA; [email protected] 6 Division of Maternal and Child Health Research and Analysis, Bureau of Family Health and Nutrition Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Boston, MA 02108, USA; [email protected] 7 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina, Charlotte, NC 28204, USA; [email protected] 8 Department of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, MA 02118, USA; Citation: Stern, J.E.; Liu, C.-l.; [email protected] Hwang, S.S.; Dukhovny, D.; Farland, * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-603-252-0696 L.V.; Diop, H.; Coddington, C.C.; Cabral, H. Influence of Placental Abstract: Objective. Assisted reproductive technology (ART)-treated women exhibit increased risk Abnormalities and Pregnancy- of premature delivery compared to fertile women. -

Global Justice Fellowship 2017–2018 Fellows and Staff Bios

GLOBAL JUSTICE FELLOWSHIP 2017–2018 FELLOWS AND STAFF BIOS The AJWS Global Justice Fellowship is a selective program designed to inspire, educate and train key opinion leaders in the American Jewish community to become advocates in support of U.S. policies that will help improve the lives of people in the developing world. AJWS has launched the latest Global Justice Fellowship program, which will include leading rabbis from across the United States. The fellowship period is from October (2017) to April (2018) and includes travel to an AJWS country in Mesoamerica, during which participants will learn from grassroots activists working to overcome poverty and injustice. The travel experience will be preceded by innovative trainings that will prepare rabbis to galvanize their communities and networks to advance AJWS’s work. Fellows will also convene in Washington, D.C. to serve as key advocates to impact AJWS’s priority policy areas. The 14 fellows represent a broad array of backgrounds, communities, experiences and networks. RABBINIC FELLOWS LAURA ABRASLEY NOAH FARKAS Rabbi Laura J. Abrasley is a rabbi Rabbi Noah Farkas serves at Valley at Temple Shalom in Newton, Beth Shalom (VBS), the largest Massachusetts. She has served this congregation in California’s San congregation since July of 2015, Fernando Valley. He was ordained and is committed to inspiring and at the Jewish Theological Seminary implementing active, engaged in 2008, and before joining VBS, opportunities for connection, community, lifelong he served as the rabbi at Congregation Beth Israel in Jewish learning and tikkun olam—repairing the world— Biloxi, Mississippi, where he helped rebuild the Jewish among her congregants.