La Verendrye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britain's Magnificent “Forts”

Britain’s Magnificent “Forts” The Freedom Freighters of WW 2 By Geoff Walker For our non-seafaring friends, many would associate the word “Fort” with some kind of medieval bastion or land based strong hold, but in the case to hand, nothing could be further from reality. Fort was the name given to a class of Cargo Ship built in Canada during WW2, for the British government (MOWT), under the Lend Lease scheme. All Fort ships, except two which were paid for outright, were transferred on bareboat charter, on Lend - lease terms, from the Canadian Government or the U.S. War Shipping Administration who bought ninety of the 'Forts' built in Canada. The construction of this type of ship commenced in 1942, and by war’s end well over 230 of these vessels had been delivered to the MOWT, (including all “Fort” variants and those built as Tankers) each at an average cost of $1,856,500. Often, confusion persists between “Fort” and “Park” class ships that were built in Canada. To clarify, “Fort” ships were ships transferred to the British Government and the “Park” ships were those employed by the Canadian Government, both types had similar design specifications. All Fort ships were given names prefixed by the word “Fort”, whilst “Park” ships all had names ending or suffixed with “Park” at the time of their launching, although names were frequently changed later during their working life. These ships were built across eighteen different Canadian shipyards. Their triple expansion steam engines were built by seven different manufacturers. There were 3 sub-classes of the type, namely, “North Sands” type which were mainly of riveted construction, and the “Canadian” and “Victory” types, which were of welded construction. -

La Vérendrye and His Sons After 1743 Is Anti‐Climactric

La Verendrye and His Sons The Search for the Western Sea Above: The Brothers La Vérendrye in sight of the western mountains, News Year’s Day 1743. By C.W. Jeffery’s. Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de la Vérendrye, and his sons were the last important explorers during the French regime in Canada. Like many of their predecessors, they pushed westward in spite of lack of support from the king or his officials in Quebec, and in spite of the selfishness and greed of the merchants, who equipped their expeditions only to take all of the large profits of the fur trade made possible by energetic exploration. La Vérendrye was born on November 17, 1685, in the settlements of Three Rivers, where his father was governor. *1 He entered the army as a cadet in 1697. In 1704 he took part in a raid upon Deerfield, a settlement in the British colony of Massachusetts, and in 1705 he fought under Subercase when a French force raided St. John’s, Newfoundland. In 1707 La Vérendrye went to Europe and served with a regiment in Flanders against the English under the Duke of Marlborough. At the battle of Malplaquet (1710) he was wounded several times. Upon his recovery he was promoted to lieutenant, and in 1711 returned to Canada. For several years La Vérendrye served in the colonial forces. In 1712 he married and settled on the island of Dupas, near Three Rivers. There his four sons were born – Jean‐Baptiste, Pierre, Francois, and Louis‐Joseph. In 1726 La Vérendrye received the command of a trading post on Lake Nipigon, north of Lake Superior. -

About Portage La Prairie Portage La Prairie

About Portage la Prairie Portage la Prairie... The City of Possibilities! From the beginning, the site for Portage la Prairie has been ideal for transportation, trade, growth and beauty. Photo courtesy of Dennis Wiens Photo courtesy of Dennis Photo courtesy of Diane VanAert Photo courtesy of John Nielsen hen Canada’s vast western lands were wild and free, this was the Wplace on the Assiniboine River known as “Prairie Portage” — the swift- est overland link between the waters of the Assiniboine and Red River systems and those of Lake Manitoba. Portage la Prairie’s place in the world has grown with the times from its rich history to a present day bustling business centre. Located in south central Manitoba on the picturesque Assiniboine River, Portage la Prairie is, and has always been, an important transportation cen- tre, dating back to its inception as a fur trading post. Today, it is connected to the rest of Canada via the Trans-Canada Yellowhead Highway systems, with service from both major railroads, a trans-continental bus service, and air through Southport. Strategically situated in the centre of the continent astride major east- west transportation routes, (only forty-five minutes west of Winnipeg, one hour north of the international border, and one hour east of Brandon) Portage la Prairie is in an ideal position to accommodate additional 3 About Portage la Prairie industries. Residents of Portage la Prairie utilize the Assiniboine River as their water source. A flood-con- trol dam provides an ideal reservoir which ensures more than adequate water supply for all the community’s needs. -

2018 Conference Program Thursday, September 20 7:00 – 9:00 Opening Reception, Steinbach Cultural Arts Centre

Association of Manitoba Museums Conference & AGM 2018 Mennonite Heritage Village Steinbach MB September 20 - 22, 2018 Unrivaled Collections Management Software for Progressive Museums of all Sizes and Budgets Leverage Argus & ArgusEssentia to make your collection more visible, accessible and relevant than ever before! • Off-the-shelf yet adaptable • Full multimedia support • Mobile access for visitors and staff • Search Engine integration • Integrated Portal • Metrics and reporting • Crowdsourced curation (moderated) Whether you are a large, multi-site museum or a small museum focused on delivering big impact, our products enable you to overcome challenges to access, visibility and sharing. • You can publish your collection online • You can attract more visitors to your website • You can integrate your collection information with other systems and databases Today’s museum professionals successfully address challenges and embrace opportunities, with Argus & ArgusEssentia Call us at 604-278-6717, or visit www.lucidea.com/argus Thank you to: Our Donors Our Supporters Monique Brandt Buhler Gallery, St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg Sport, Culture and Heritage Sherry Dangerfield Fort Dauphin Museum, Dauphin Morris & District Centennial Museum, Morris New Iceland Heritage Museum, Gimili Leslie Poulin Peter Priess Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada, Winnipeg Our Hosts Sam Waller Museum, The Pas Mennonite Heritage Village Museum Beryth Strong Our apologies to any supporters we may have missed Winnipegosis Historical Society, Winnipegosis when compiling these lists. Acknowledgment The Association of Manitoba Museums acknowledges that we are on Treaty 1 territory and the land on which we gather is the traditional territory of Anishinaabeg, Cree, Oji-Cree, Dakota, and Dene Peoples, and the homeland of the Métis Nation. -

The French Regime in Wisconsin. 1 the French Regime in Wisconsin — III

Library of Congress The French regime in Wisconsin. 1 The French Regime in Wisconsin — III 1743: SIOUX INSTIGATE REBELLION; NEWS FROM ILLINOIS [Letter from the French minister1 to Beauharnois, dated May 31, 1743. MS. in Archives Coloniales, Paris; pressmark, “Amérique, serie B, Canada, vol. 76, fol. 100.”] 1 From 1723–49, the minister of the marine (which included the bureau of the colonies), was Jean Freédeéric Phelypeaux, Comte de Maurepas.— Ed. Versailles , May 31, 1743. Monsieur —The report you made me in 1741 respecting what had passed between the Scioux and Renard Savages2 having led me to suspect that both would seek to join together, I wrote you in my despatch of April 20th of last year to neglect nothing to prevent so dangerous a union. Such suspicions are only too fully justified. In fact I see by a letter from Monsieur de Bienville,3 dated February 4th last, that the Sieur de Bertet, major commanding at Illinois4 has informed him that the voyageurs who had arrived from Canada the previous autumn had reported to him that the Scioux, not content with having broken the peace they themselves had gone to ask of you, had also induced the Renards to join them in a fresh attempt against the French, and that the Sakis not wishing to take part in this league had wholly separated themselves from the other tribes. 1 2 See Wis. Hist. Colls., xvii, pp. 360–363.— Ed. 3 For a brief sketch of Bienville, see Ibid., p. 150, note 1.— Ed. 4 For this officer see Ibid., p. -

2.0 Native Land Use - Historical Period

2.0 NATIVE LAND USE - HISTORICAL PERIOD The first French explorers arrived in the Red River valley during the early 1730s. Their travels and encounters with the aboriginal populations were recorded in diaries and plotted on maps, and with that, recorded history began for the region known now as the Lake Winnipeg and Red River basins. Native Movements Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye records that there were three distinct groups present in this region during the 1730s and 1740s: the Cree, the Assiniboine, and the Sioux. The Cree were largely occupying the boreal forest areas of what is now northern and central Manitoba. The Assiniboine were living and hunting along the parkland transitional zone, particularly the ‘lower’ Red River and Assiniboine River valleys. The Sioux lived on the open plains in the region of the upper Red River valley, and west of the Red River in upper reaches of the Mississippi water system. Approximately 75 years later, when the first contingent of Selkirk Settlers arrived in 1812, the Assiniboine had completely vacated eastern Manitoba and moved off to the west and southwest, allowing the Ojibwa, or Saulteaux, to move in from the Lake of the Woods and Lake Superior regions. Farther to the south in the United States, the Ojibwa or Chippewa also had migrated westward, and had settled in the Red Lake region of what is now north central Minnesota. By this time some of the Sioux had given up the wooded eastern portions of their territory and dwelt exclusively on the open prairie west of the Red and south of the Pembina River. -

Staying STRONG

Staying STRONG 2019/2020 Annual Report TABLE of CONTENTS 5 Message from the Board Chair and President & CEO 7 About Travel Manitoba 8 The Tourism Industry in Manitoba 9 Lead the Implementation of the Provincial Tourism Strategy 16 Align Partners and Foster Collaboration 17 Lead the Brand and Market Positioning 17 • Research and Market Intelligence 20 • Content Marketing 26 • Digital Marketing 28 • Fishing and Hunting Marketing 31 Meetings, Conventions, Major Events and Incentive Travel 32 Domestic Marketing 33 International Marketing 40 Awards 41 Visitor Services 42 Increase Public Awareness of Tourism 43 Looking Ahead: The Impact of COVID-19 44 Our Partners 46 Board of Directors & Travel Manitoba Staff 47 Financial Statements ON THE FortWhyte Alive Riding Mountain National Park COVER PHOTO BY ERICK STOEN 2 STAYING STRONG 2019/20 ANNUAL REPORT 3 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR AND PRESIDENT & CEO Nothing will show Manitoba’s resiliency, its resolve and its Indicative of the growth in community engagement are factors character like its return from the devastation of COVID-19. Fiscal such as the $1.1 million we achieved in industry partnership year 2019/20 was one that began with triumphs and tributes, revenues, and the fact that more Manitobans indicate that the as Manitoba continued to celebrate its designation as one of Manitoba…Canada’s Heart Beats campaign has improved their Lonely Planet’s Top 10 regions to visit on the planet, and ended opinion of their home province. As the premier destination like every other destination on the planet, forced to shutter its content publisher in the province, Travel Manitoba continued tourism industry as an unprecedented pandemic raged to increase its audience, with Facebook fans growing by 27% in worldwide. -

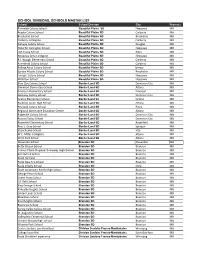

School Divisions, Schools Master List

SCHOOL DIVISIONS, SCHOOLS MASTER LIST School School Division City Province Riverside Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Neepawa MB Acadia Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Carberry MB Brookdale School Beautiful Plains SD Brookdale MB Carberry Collegiate Beautiful Plains SD Carberry MB Fairway Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Douglas MB Hazel M. Kellington School Beautiful Plains SD Neepawa MB J.M.Young School Beautiful Plains SD Eden MB Neepawa Area Collegiate Beautiful Plains SD Neepawa MB R.J. Waugh Elementary School Beautiful Plains SD Carberry MB Riverbend Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Carberry MB Rolling Acres Colony School Beautiful Plains SD birnue MB Spruce Woods Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Brookdale MB Twilight Colony School Beautiful Plains SD Neepawa MB Willerton School Beautiful Plains SD Neepawa MB Blue Clay Colony School Border Land SD Dominion City MB Elmwood Elementary School Border Land SD Altona MB Emerson Elementary School Border Land SD Emerson MB Glenway Colony School Border Land SD Dominion City MB Gretna Elementary School Border Land Sd Gretna MB Parkside Junior High School Border Land SD Altona MB Pineland Colony School Border Land SD Piney MB Regional Alternative Education Centre Border Land SD Altona MB Ridgeville Colony School Border Land SD Dominion City MB Roseau Valley School Border Land SD Dominion City MB Rosenfeld Elementary School Border Land SD Rosenfeld MB Ross L. Gray School Border Land SD Sprague MB Shevchenko School Border Land SD Vita MB W.C. Miller Collegiate Border Land SD Altona MB West Park School Border Land SD Altona MB Alexander School Brandon SD Alexander MB Betty Gibson School Brandon SD Brandon MB Crocus Plains Regional Seconday High School Brandon SD Brandon MB Earl Oxford School Brandon SD Brandon MB Ecole Harrison Brandon SD Brandon MB Ecole New Era School Brandon SD Brandon MB Ecole O'Kelly School Brandon SD Shilo MB Ecole secondaire Neelin High School Brandon SD Brandon MB George Fitton School Brandon SD Brandon MB Green Acres School Brandon SD Brandon MB J.R. -

A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume II

A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume II Francis Parkman The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Half-Century of Conflict, by Francis Parkman #5 in our series by Francis Parkman Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume II Author: Francis Parkman Release Date: December, 2004 [EBook #7064] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on March 5, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A HALF-CENTURY OF CONFLICT *** Produced by Don Kretz, David Moynihan, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. A HALF-CENTURY OF CONFLICT BY FRANCIS PARKMAN VOL. II CONTENTS CHAPTER XV. 1697-1741. FRANCE IN THE FAR WEST. -

A Tabloid History of Montana

ATabloidHistoryofMontana by Bob Fletcher This Tabloid History of Montana or "The Pioneer History of the Land of Shining Mountains" appeared on the reverse side of a historical map published by the Montana Highway Commission in 1937. Scientists tell a fascinating tale of prehistoric Montana in which these erudite gentlemen toss offmillions of years in the nonchalant manner of a Congressman speaking of a billion dollar appropriation. Such figures are just too large for our average five-and-ten minds to grasp. In the dim and distant past most of Montana's framework was built under water in horizontal layers of sedimentary rocks. Later a portion was lifted and formed the shore line and coastal plain of a shallow marshy arm of the great sea which covered America from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. The climate was the sort that Florida real estate men brag about. Sashaying through the tropical vegetation were the mean looking reptiles we call dinosaurs. Now fossil hunters find their skeletons sealed in the rocks that formed the prehistoric mud and ooze. Next Dame Nature developed a gigantic stomach ache in western Montana that caused her erstwhile placid countenance to crease with anguish. The largest wrinkles are the mountain ranges, the troughs between are structural valleys. The corrugations broadened and tapered offacross eastern Montana into gently sloping anticlines. Hell boiled over in the west. Restless molten masses beneath the sedimentaries bulged and fractured them; volcanic ash deluged the valleys, and lava sheets flowed down the mountain sides. Central Montana broke out in a rash. -

Francis Parkman a Half Century of Conflict

FRANCIS PARKMAN A HALF CENTURY OF CONFLICT VOLUME II 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted A HALF-CENTURY OF CONFLICT BY FRANCIS PARKMAN VOL. II CONTENTS CHAPTER XV. 1697-1741. FRANCE IN THE FAR WEST. French Explorers.--Le Sueur on the St. Peter's.--Canadians on the Missouri.--Juchereau de Saint-Denis.--Bénard de la Harpe on Red River.--Adventures of Du Tisné.--Bourgmont visits the Comanches.--The Brothers Mallet in Colorado and New Mexico.--Fabry de la Bruyère. CHAPTER XVI. 1716-1761. SEARCH FOR THE PACIFIC. The Western Sea.--Schemes for reaching it.--Journey of Charlevoix.--The Sioux Mission.--Varennes de la Vérendrye.--His Enterprise.--His Disasters.--Visits the Mandans.--His Sons.--Their Search for the Western Sea.--Their Adventures.--The Snake Indians.--A Great War-Party.--The Rocky Mountains.--A Panic.--Return of the Brothers.--Their Wrongs and their Fate. CHAPTER XVII. 1700-1750. THE CHAIN OF POSTS. Opposing Claims.--Attitude of the Rival Nations.--America a French Continent.--England a Usurper.--French Demands.--Magnanimous Proposals.--Warlike Preparation.--Niagara.--Oswego.--Crown Point.--The Passes of the West secured. CHAPTER XVIII. 1744, 1745. A MAD SCHEME. War of the Austrian Succession.--The French seize Canseau and attack Annapolis.--Plan of Reprisal.--William Vanghan.--Governor Shirley.--He advises an Attack on Louisbourg.--The Assembly refuses, but at last consents.--Preparation.--William Pepperrell.--George Whitefield.--Parson Moody.--The Soldiers.--The Provincial Navy.--Commodore Warren.--Shirley as an Amateur Soldier.--The Fleet sails. CHAPTER XIX. 1745. LOUISBOURG BESIEGED. Seth Pomeroy.--The Voyage.--Canseau.--Unexpected Succors.--Delays. --Louisbourg.--The Landing.--The Grand Battery taken.--French Cannon turned on the Town.--Weakness of Duchambon.--Sufferings of the Besiegers.--Their Hardihood.--Their Irregular Proceedings.--Joseph Sherburn.--Amateur Gunnery.--Camp Frolics.--Sectarian Zeal.--Perplexities of Pepperrell. -

Lewis and Clark's French Passport: a Preq1tel to the Corps of Discovery by Charles E

8 JCHS JOUR.NAL AUTUMN 2004 LEWIS AND CLARK'S FRENCH PASSPORT: A PREQ1TEL TO THE CORPS OF DISCOVERY BY CHARLES E. HOFFHAUS The well-merited media exposure regarding the Lewis & Louis' orders to Charlevoix so many years earlier. Clark Bicentennial has thrown some light on a little-known \>\fith Louis XV's approval, the Sieur de La Verendrye fact: colonial France attempted its own version of a Voyage of was granted a license from the Canadian Governor in 1730 to Discovery in the American West in the 1740s. enter Canada's westernmost domains in order to explore the This early effort found French King Louis XV in route to the Sea of the West-but provided he did the role later played by President Jefferson, acting so at no expense to I-lis Majesty. This penurious upon very similar concerns regarding rival powers policy of the Crown forced La Verendrye to (England, Spain an Russia), and a nas cent French engage in the fur trading bu sine ss on the side to "manifest destiny)) sentiment. So the clarion ca ll make ends meet, and eventually to reso rt to huge went out to the colonial Governor in Qlcbec: find private loans, neither of which expedients helped the River of the West leading to the \>\festern Sea his or the governm ent's cause. (Pacific Ocean) and the Orient ... and do it fast! La Verendr),e had four sons, three of The similarities in the two nations' exploration whorn, plus a nephew, participated in his early efforts arc fascinating. For France, the rnantle explorations westward, beginning June 8, 1731.