Celsr1 Is Required for the Generation of Polarity at Multiple Levels of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcriptomic Analysis of Native Versus Cultured Human and Mouse Dorsal Root Ganglia Focused on Pharmacological Targets Short

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/766865; this version posted September 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. Transcriptomic analysis of native versus cultured human and mouse dorsal root ganglia focused on pharmacological targets Short title: Comparative transcriptomics of acutely dissected versus cultured DRGs Andi Wangzhou1, Lisa A. McIlvried2, Candler Paige1, Paulino Barragan-Iglesias1, Carolyn A. Guzman1, Gregory Dussor1, Pradipta R. Ray1,#, Robert W. Gereau IV2, # and Theodore J. Price1, # 1The University of Texas at Dallas, School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences and Center for Advanced Pain Studies, 800 W Campbell Rd. Richardson, TX, 75080, USA 2Washington University Pain Center and Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine # corresponding authors [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] Funding: NIH grants T32DA007261 (LM); NS065926 and NS102161 (TJP); NS106953 and NS042595 (RWG). The authors declare no conflicts of interest Author Contributions Conceived of the Project: PRR, RWG IV and TJP Performed Experiments: AW, LAM, CP, PB-I Supervised Experiments: GD, RWG IV, TJP Analyzed Data: AW, LAM, CP, CAG, PRR Supervised Bioinformatics Analysis: PRR Drew Figures: AW, PRR Wrote and Edited Manuscript: AW, LAM, CP, GD, PRR, RWG IV, TJP All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/766865; this version posted September 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Celsr1-3 Cadherins in PCP and Brain Development

CHAPTER SEVEN Celsr1–3 Cadherins in PCP and Brain Development Camille Boutin, André M. Goffinet1, Fadel Tissir1 Institute of Neuroscience, Developmental Neurobiology, Universite´ Catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium 1Corresponding authors: Equal contribution. e-mail address: [email protected]; andre. [email protected] Contents 1. Celsr1–3 Expression Patterns 164 2. Celsr1: A Major Player in Vertebrate PCP 165 3. Celsr2 and 3 in Ciliogenesis 169 4. Celsr1–3 in Neuronal Migration 171 5. Celsr2 and Celsr3 in Brain Wiring 174 5.1 Motifs of Celsr important for their functions 176 References 179 Abstract Cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptors 1, 2, and 3 (Celsr1–3) form a family of three atypical cadherins with multiple functions in epithelia and in the nervous system. During the past decade, evidence has accumulated for important and distinct roles of Celsr1–3 in planar cell polarity (PCP) and brain development and maintenance. Although the role of Celsr in PCP is conserved from flies to mammals, other functions may be more distantly related, with Celsr working only with one or a subset of the classical PCP partners. Here, we review the literature on Celsr in PCP and neural devel- opment, point to several remaining questions, and consider future challenges and possible research trends. Celsr1–3 genes encode atypical cadherins of more than 3000 amino acids ( Fig. 7.1). Their large ectodomain is composed of nine N-terminal cadherin repeats (typical cadherins have five repeats), six epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains, two laminin G repeats, one hormone receptor motif (HRM), and a G-protein-coupled receptor proteolytic site (GPS). -

Genetic Evidence That Celsr3 and Celsr2, Together with Fzd3, Regulate Forebrain Wiring in a Vangl-Independent Manner

Genetic evidence that Celsr3 and Celsr2, together with Fzd3, regulate forebrain wiring in a Vangl-independent manner Yibo Qua, Yuhua Huanga, Jia Fenga, Gonzalo Alvarez-Boladob, Elizabeth A. Grovec, Yingzi Yangd, Fadel Tissire, Libing Zhoua,f,1,2, and Andre M. Goffinete,1,2 aGuangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Institute of CNS Regeneration, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China; bDepartment of Neuroanatomy, Heidelberg University, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany; cNeuroscience, The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637; dNational Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; eWELBIO - Walloon Excellence in Life Sciences and Biotechnology and Institute of Neuroscience, University of Louvain, B1200 Brussels, Belgium; and fState Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Edited* by Jeremy Nathans, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, and approved June 18, 2014 (received for review February 3, 2014) Celsr3 and Fzd3, members of “core planar cell polarity” (PCP) AC contains commissural axons from the anterior olfactory nu- genes, were shown previously to control forebrain axon guidance clei and from the temporal cortex, which cross the midline at and wiring by acting in axons and/or guidepost cells. Here, we embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) to E14.5 (11–14). The IC contains show that Celsr2 acts redundantly with Celsr3, and that their com- three main axonal components. Thalamocortical axons (TCA) bined mutation mimics that of Fzd3. The phenotypes generated emerge from the thalamus—formerly called “dorsal” thalamus upon inactivation of Fzd3 in different forebrain compartments are (15)—at E12.5. They run through the prethalamus (former similar to those in conditional Celsr2-3 mutants, indicating that “ventral” thalamus), turn and cross the diencephalon–telen- Fzd3 and Celsr2-3 act in the same population of cells. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2015) 172, 5744–5869 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1, Anthony P Davenport2, Eamonn Kelly3, Neil Marrion3, John A Peters4, Helen E Benson5, Elena Faccenda5, Adam J Pawson5, Joanna L Sharman5, Christopher Southan5, Jamie A Davies5 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK, 2Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK, 3School of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK, 4Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK, 5Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 provides concise overviews of the key properties of over 1750 human drug targets with their pharmacology, plus links to an open access knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. The full contents can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ 10.1111/bph.13348/full. G protein-coupled receptors are one of the eight major pharmacological targets into which the Guide is divided, with the others being: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, other ion channels, nuclear hormone receptors, catalytic receptors, enzymes and transporters. These are presented with nomenclature guidance and summary information on the best available pharmacological tools, alongside key references and suggestions for further reading. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

G Protein‐Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2019) 176, S21–S141 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1 , Arthur Christopoulos2 , Anthony P Davenport3 , Eamonn Kelly4, Alistair Mathie5 , John A Peters6 , Emma L Veale5 ,JaneFArmstrong7 , Elena Faccenda7 ,SimonDHarding7 ,AdamJPawson7 , Joanna L Sharman7 , Christopher Southan7 , Jamie A Davies7 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK 2Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia 3Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK 4School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK 5Medway School of Pharmacy, The Universities of Greenwich and Kent at Medway, Anson Building, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime, Chatham, Kent, ME4 4TB, UK 6Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK 7Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 is the fourth in this series of biennial publications. The Concise Guide provides concise overviews of the key properties of nearly 1800 human drug targets with an emphasis on selective pharmacology (where available), plus links to the open access knowledgebase source of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. Although the Concise Guide represents approximately 400 pages, the material presented is substantially reduced compared to information and links presented on the website. -

Supplemetary Table 2. List of Genes Down-Regulated in LPAR6 Knocked Down Cells

Supplemetary Table 2. List of genes down-regulated in LPAR6 knocked down cells g# initial alias c# converted alias name description namespace 1 NM_002317.5 1.1 ENSG00000113083 LOX lysyl oxidase [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:6664] REFSEQ_MRNA 2 NM_006183.4 2.1 ENSG00000133636 NTS neurotensin [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:8038] REFSEQ_MRNA 3 NM_005213.3 3.1 ENSG00000121552 CSTA cystatin A (stefin A) [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2481] REFSEQ_MRNA 4 NM_007231.3 4.1 ENSG00000087916 SLC6A14 solute carrier family 6 (amino acid transporter), member 14 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:11047] REFSEQ_MRNA 5 NM_001873.2 5.1 ENSG00000109472 CPE carboxypeptidase E [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2303] REFSEQ_MRNA 6 NM_019856.1 6.1 ENSG00000101605 MYOM1 myomesin 1, 185kDa [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:7613] REFSEQ_MRNA 7 NM_032590.4 7.1 ENSG00000089094 KDM2B lysine (K)-specific demethylase 2B [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:13610] REFSEQ_MRNA 8 NM_001901.2 8.1 ENSG00000118523 CTGF connective tissue growth factor [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:2500] REFSEQ_MRNA 9 NM_007183.2 9.1 ENSG00000184363 PKP3 plakophilin 3 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:9025] REFSEQ_MRNA 10 NM_182965.2 10.1 ENSG00000176170 SPHK1 sphingosine kinase 1 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:11240] REFSEQ_MRNA 11 NM_152423.4 11.1 ENSG00000157502 MUM1L1 melanoma associated antigen (mutated) 1-like 1 [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:26583] REFSEQ_MRNA 12 NM_002923.3 12.1 ENSG00000116741 RGS2 regulator of G-protein signaling 2, 24kDa [Source:HGNC Symbol;Acc:9998] REFSEQ_MRNA 13 NR_003038.2 13.1 N/A N/A N/A N/A 14 NM_080862.1 14.1 ENSG00000175093 SPSB4 splA/ryanodine receptor -

Supplementary Data, Ms Iring Et Al. Re-Revised

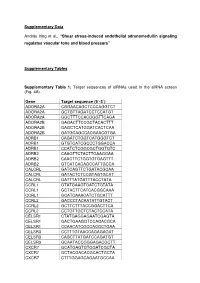

Supplementary Data András Iring et al., “Shear stress-induced endothelial adrenomedullin signaling regulates vascular tone and blood pressure” Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Target sequences of siRNAs used in the siRNA screen (Fig. 4A). Gene Target sequence (5´-3´) ADORA2A CGGAACAGCTCCCAGGTCT ADORA2A GCTGTTAGATCCTCCATGT ADORA2A GGCTTTCCACGGGTTCAGA ADORA2B GAGACTTCCGCTACACTTT ADORA2B GAGCTCATGGATCACTCAA ADORA2B GATGCAGCCACGAACGTGA ADRB1 CAGATCTGGTCATGGGTCT ADRB1 GTGTCATCGCCCTGGACCA ADRB1 CCATCTCGGCGCTGGTGTC ADRB2 CAAGTTCTACTTGAAGGAA ADRB2 CAACTTCTGGTGTGAGTTT ADRB2 GTCATCACAGCCATTGCCA CALCRL GATCAGTTCTGATACGCAA CALCRL GATACTCTCCGTAGTGCAT CALCRL GATTTATGATTTACCTATA CCRL1 GTATGAAGTGATCTGTATA CCRL1 GCTACTTCATCACGGCAAA CCRL1 GCATCAAACATCTGCATTT CCRL2 GACCCTACAATATTGTACT CCRL2 GCTTCTTTACCGGACTTCA CCRL2 CCTGTTGCTCTACTCCATA CELSR1 CTATGAGGAGAATCGAGTA CELSR1 GACTGAAGGTCCAGACGCA CELSR1 CCAACATCGCCACGCTGAA CELSR3 CCTTTGTAACCAGAGAGAT CELSR3 CAGCTTATGATCCAGATGT CELSR3 GCAATACCGGGAGACGCTT CXCR7 GCATGAGTGTGGATCGCTA CXCR7 GCTACGACACGCACTGCTA CXCR7 CTTTGGAGCAGAATGCCAA 2 ELTD1 CTCTTCTAATTCAACTCTT ELTD1 CAAGTTTATTACTAATGAT ELTD1 GTACCATACAGCTATAGTA FZD1 GTAACCAATGCCAAACTTT FZD1 GATTAGCCACCGAAATAAA FZD1 CAGTGTTCCGCCGAGCTCA FZD2 CGCTTTGCGCGCCTCTGGA FZD2 GACATGCAGCGCTTCCGCT FZD2 CGCACTACACGCCGCGCAT FZD4 GTATGTGCTATAATATTTA FZD4 CCATTGTCATCTTGATTAT FZD4 CCAACATGGCAGTGGAAAT FZD5 GGATTTAAGGCCCAGTTTA FZD5 GACCATAACACACTTGCTT FZD5 CAAGTGATCCTGGGAAAGA FZD6 GCATTGTATCTCTTATGTA FZD6 GTGCTTACTGAGTGTCCAA FZD6 CCAATTACTGTTCCCAGAT FZD8 CCATCTGCCTAGAGGACTA -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

Alexander, S. P. H., Christopoulos, A., Davenport, A. P., Kelly, E., Marrion, N. V., Peters, J. A., Faccenda, E., Harding, S. D., Pawson, A. J., Sharman, J. L., Southan, C., Davies, J. A. (2017). THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 174, S17-S129. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13878 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/bph.13878 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Wiley at https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13878 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2017) 174, S17–S129 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1, Arthur Christopoulos2, Anthony P Davenport3, Eamonn Kelly4, Neil V Marrion4, John A Peters5, Elena Faccenda6, Simon D Harding6,AdamJPawson6, Joanna L Sharman6, Christopher Southan6, Jamie A Davies6 and CGTP Collaborators 1 School of Life Sciences, -

A Molecular Map of Murine Lymph Node Blood Vascular Endothelium at Single Cell Resolution

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17291-5 OPEN A molecular map of murine lymph node blood vascular endothelium at single cell resolution Kevin Brulois1,13, Anusha Rajaraman1,2,3,13, Agata Szade 1,4,13,Sofia Nordling1,13, Ania Bogoslowski 5,6, Denis Dermadi 1, Milladur Rahman 1, Helena Kiefel1, Edward O’Hara1, Jasper J. Koning3, Hiroto Kawashima7, Bin Zhou 8, Dietmar Vestweber 9, Kristy Red-Horse10, Reina E. Mebius3, Ralf H. Adams 11, ✉ Paul Kubes 5,6, Junliang Pan1,2 & Eugene C. Butcher1,2,12 1234567890():,; Blood vascular endothelial cells (BECs) control the immune response by regulating blood flow and immune cell recruitment in lymphoid tissues. However, the diversity of BEC and their origins during immune angiogenesis remain unclear. Here we profile transcriptomes of BEC from peripheral lymph nodes and map phenotypes to the vasculature. We identify multiple subsets, including a medullary venous population whose gene signature predicts a selective role in myeloid cell (vs lymphocyte) recruitment to the medulla, confirmed by videomicro- scopy. We define five capillary subsets, including a capillary resident precursor (CRP) that displays stem cell and migratory gene signatures, and contributes to homeostatic BEC turnover and to neogenesis of high endothelium after immunization. Cell alignments show retention of developmental programs along trajectories from CRP to mature venous and arterial populations. Our single cell atlas provides a molecular roadmap of the lymph node blood vasculature and defines subset specialization for leukocyte recruitment and vascular homeostasis. 1 Laboratory of Immunology and Vascular Biology, Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA. -

Br J Pharmacol

Supplementary Information Supplementary Table 1. List of polypeptide cell surface receptor and their cognate ligand genes. Supplementary Table 2. List of coding SNPs with high FST ( > 0.5) in human GPCR and their cognate ligand genes. Supplementary Table 3. List of coding SNPs with high FST ( > 0.5) in human nonGPCR receptor and ligand genes. Supplementary Table 4. List of genotyped SNPs from 44246961 to 44542055 on chromosome 17. The HapMap II dataset was analyzed using HaploView. The 101 SNPs included in LD plots of Supplementary Fig. 3 (A-C) are highlighted by a grey background. The 37 SNPs used in the haplotype analysis of Fig. 2C are indicated by red letters. SNPs that are linked with rs2291725 are indicated by bold red letters. Supplementary Table 5. Allele frequency of rs2291725 in the HGDP-CEPH populations. Frequencies of GIP103T and GIP103C alleles in each of the 52 populations from the seven geographical regions and the number of chromosomes analyzed for each population. 1 Supplementary Table 6. EC50 values for GIP receptor activation at four different time points after incubation with pooled human serum or pooled complement-preserved human serum (N=4). Supplementary Table 7. EC50 values for GIP receptor activation at three different time points after incubation with a recombinant DPP IV enzyme (N=4). Supplementary Fig. 1. Cumulative distribution function (CDF) plots for the FST of coding SNPs in human GPCRs and their cognate ligand genes (blue) and all other human genes (magenta). The FST was computed between three HapMap II populations (CEU, YRI, and ASN), and coding SNPs have been split into synonymous and nonsynonymous groups. -

Continuously Active Transcriptional Programs Are Required to Build Expansive Serotonergic Axon Architectures

CONTINUOUSLY ACTIVE TRANSCRIPTIONAL PROGRAMS ARE REQUIRED TO BUILD EXPANSIVE SEROTONERGIC AXON ARCHITECTURES By LAUREN JANINE DONOVAN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Evan S. Deneris Department of Neurosciences CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January 2020 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Lauren Janine Donovan candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy*. Committee Chair Jerry Silver, Ph.D. Committee Member Evan Deneris, Ph.D. Committee Member Heather Broihier, Ph.D. Committee Member Ron Conlon, Ph.D. Committee Member Pola Philippidou, Ph.D. Date of Defense August 29th, 2019 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures……………………………………………………………………….….vii Abstract………………………………………….………………………………..….…1 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………...……..3 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO SEROTONIN………………………………….….4 Serotonin: Discovery and function………………………….……………...4 Serotonin Biosynthesis…………………………..…………………………..6 Manipulation of the serotonin system in humans……………………….6 Human mutations in 5-HT related genes………………………………….9 SEROTONIN NEURON NEUROGENESIS……………..………………………….11 5-HT neuron specification……………..………………………………...…11 Development of 5-HT neurons……………..………………………………13 NEUROANATOMY……………..……………………………………………………..13 Cytoarchitecture ……………..………………………………………………13 Adult Ascending 5-HT axon projection system ………………………..14