Conservation Assessment for Pitcher's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caryophyllaceae) in Iran

International Journal of Modern Botany 2014, 4(1): 8-21 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijmb.20140401.02 Pollen Micro-morphology of the Minuartia Species (Caryophyllaceae) in Iran Golaleh Mostafavi1,*, Iraj Mehregan2 1Department of Biology, College of Basic Sciences, Yadegar-e-Imam, Khomeini (RAH) Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Department of Biology, Science and Research Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran-Iran Abstract The present study compared pollen micro-morphological characters among 20 Iranian Minuartia species. For this purpose, mature pollen grains taken from unopened flowers, were prepared, fixed and exhaustively investigated using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). In order to perform the pollen micro-morphology of Minuartia, and to find its significance in taxonomy of the group, qualitative and quantitative variables related to the shape, size, ornamentations and pores were studied. Cluster and PCA analyses of qualitative and quantitative data were performed to demonstrate the pollen grain similarities among the species. According to our results, Minuartia species exhibit either sub-spherical or polyhedral pollen shapes. Pollen size also varies among different species. The longest polar axis length (P) belongs to Minuartia meyeri Bornm. (34.3±0.26µm) and the smallest one to M. montana L. (15.8±0.26µm). Pore ornamentations differ from prominent granular to slightly or distinctly sunken granular. The number of pores also varies considerably depending on species. It ranges from 10 (in M. meyeri and M. acuminata Turrill) to 24 (in M. subtilis Hand.-Mazz.) on two pollen hemispheres. The most reliable characters in this study were pore diameter (annulus included) (D), equatorial diameter (E), polar axis length (P), the distance between two pores (d), pollen outline, Pore diameter (annulus excluded) (R), annulus diameter (a), P/E ratio, Puncta diameter and Echini diameter respectively. -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Species List For: Valley View Glades NA 418 Species

Species List for: Valley View Glades NA 418 Species Jefferson County Date Participants Location NA List NA Nomination and subsequent visits Jefferson County Glade Complex NA List from Gass, Wallace, Priddy, Chmielniak, T. Smith, Ladd & Glore, Bogler, MPF Hikes 9/24/80, 10/2/80, 7/10/85, 8/8/86, 6/2/87, 1986, and 5/92 WGNSS Lists Webster Groves Nature Study Society Fieldtrip Jefferson County Glade Complex Participants WGNSS Vascular Plant List maintained by Steve Turner Species Name (Synonym) Common Name Family COFC COFW Acalypha virginica Virginia copperleaf Euphorbiaceae 2 3 Acer rubrum var. undetermined red maple Sapindaceae 5 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple Sapindaceae 2 -3 Acer saccharum var. undetermined sugar maple Sapindaceae 5 3 Achillea millefolium yarrow Asteraceae/Anthemideae 1 3 Aesculus glabra var. undetermined Ohio buckeye Sapindaceae 5 -1 Agalinis skinneriana (Gerardia) midwestern gerardia Orobanchaceae 7 5 Agalinis tenuifolia (Gerardia, A. tenuifolia var. common gerardia Orobanchaceae 4 -3 macrophylla) Ageratina altissima var. altissima (Eupatorium rugosum) white snakeroot Asteraceae/Eupatorieae 2 3 Agrimonia pubescens downy agrimony Rosaceae 4 5 Agrimonia rostellata woodland agrimony Rosaceae 4 3 Allium canadense var. mobilense wild garlic Liliaceae 7 5 Allium canadense var. undetermined wild garlic Liliaceae 2 3 Allium cernuum wild onion Liliaceae 8 5 Allium stellatum wild onion Liliaceae 6 5 * Allium vineale field garlic Liliaceae 0 3 Ambrosia artemisiifolia common ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 3 Ambrosia bidentata lanceleaf ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 4 Ambrosia trifida giant ragweed Asteraceae/Heliantheae 0 -1 Amelanchier arborea var. arborea downy serviceberry Rosaceae 6 3 Amorpha canescens lead plant Fabaceae/Faboideae 8 5 Amphicarpaea bracteata hog peanut Fabaceae/Faboideae 4 0 Andropogon gerardii var. -

Buchbesprechungen 247-296 ©Verein Zur Erforschung Der Flora Österreichs; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Neilreichia - Zeitschrift für Pflanzensystematik und Floristik Österreichs Jahr/Year: 2006 Band/Volume: 4 Autor(en)/Author(s): Mrkvicka Alexander Ch., Fischer Manfred Adalbert, Schneeweiß Gerald M., Raabe Uwe Artikel/Article: Buchbesprechungen 247-296 ©Verein zur Erforschung der Flora Österreichs; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Neilreichia 4: 247–297 (2006) Buchbesprechungen Arndt KÄSTNER, Eckehart J. JÄGER & Rudolf SCHUBERT, 2001: Handbuch der Se- getalpflanzen Mitteleuropas. Unter Mitarbeit von Uwe BRAUN, Günter FEYERABEND, Gerhard KARRER, Doris SEIDEL, Franz TIETZE, Klaus WERNER. – Wien & New York: Springer. – X + 609 pp.; 32 × 25 cm; fest gebunden. – ISBN 3-211-83562-8. – Preis: 177, – €. Dieses imposante Kompendium – wohl das umfangreichste Werk zu diesem Thema – behandelt praktisch alle Aspekte der reinen und angewandten Botanik rund um die Ackerbeikräuter. Es entstand in der Hauptsache aufgrund jahrzehntelanger Forschungs- arbeiten am Institut für Geobotanik der Universität Halle über Ökologie und Verbrei- tung der Segetalpflanzen. Im Zentrum des Werkes stehen 182 Arten, die ausführlich behandelt werden, wobei deren eindrucksvolle und umfassende „Porträt-Zeichnungen“ und genaue Verbreitungskarten am wichtigsten sind. Der „Allgemeine“ Teil („I.“) beginnt mit der Erläuterung einiger (vor allem morpholo- gischer, ökologischer, chorologischer und zoologischer) Fachausdrücke, darauf -

Floristic Quality Assessment Report

FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN INDIANA: THE CONCEPT, USE, AND DEVELOPMENT OF COEFFICIENTS OF CONSERVATISM Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera) the State tree of Indiana June 2004 Final Report for ARN A305-4-53 EPA Wetland Program Development Grant CD975586-01 Prepared by: Paul E. Rothrock, Ph.D. Taylor University Upland, IN 46989-1001 Introduction Since the early nineteenth century the Indiana landscape has undergone a massive transformation (Jackson 1997). In the pre-settlement period, Indiana was an almost unbroken blanket of forests, prairies, and wetlands. Much of the land was cleared, plowed, or drained for lumber, the raising of crops, and a range of urban and industrial activities. Indiana’s native biota is now restricted to relatively small and often isolated tracts across the State. This fragmentation and reduction of the State’s biological diversity has challenged Hoosiers to look carefully at how to monitor further changes within our remnant natural communities and how to effectively conserve and even restore many of these valuable places within our State. To meet this monitoring, conservation, and restoration challenge, one needs to develop a variety of appropriate analytical tools. Ideally these techniques should be simple to learn and apply, give consistent results between different observers, and be repeatable. Floristic Assessment, which includes metrics such as the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) and Mean C values, has gained wide acceptance among environmental scientists and decision-makers, land stewards, and restoration ecologists in Indiana’s neighboring states and regions: Illinois (Taft et al. 1997), Michigan (Herman et al. 1996), Missouri (Ladd 1996), and Wisconsin (Bernthal 2003) as well as northern Ohio (Andreas 1993) and southern Ontario (Oldham et al. -

A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.14 In Memory of Rebecca Ciresa Wenk, Botaness ON THE COVER Giant Forest, Sequoia National Park Photography by: Brent Paull A Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Appendix 14 – Plants of Conservation Concern Natural Resource Report NPS/SEKI/ NRR—2013/665.14 Ann Huber University of California Berkeley 41043 Grouse Drive Three Rivers, CA 93271 Adrian Das U.S. Geological Survey Western Ecological Research Center, Sequoia-Kings Canyon Field Station 47050 Generals Highway #4 Three Rivers, CA 93271 Rebecca Wenk University of California Berkeley 137 Mulford Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-3114 Sylvia Haultain Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks 47050 Generals Highway Three Rivers, CA 93271 June 2013 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate high-priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. -

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited By

New York Natural Heritage Program Rare Plant Status List May 2004 Edited by: Stephen M. Young and Troy W. Weldy This list is also published at the website: www.nynhp.org For more information, suggestions or comments about this list, please contact: Stephen M. Young, Program Botanist New York Natural Heritage Program 625 Broadway, 5th Floor Albany, NY 12233-4757 518-402-8951 Fax 518-402-8925 E-mail: [email protected] To report sightings of rare species, contact our office or fill out and mail us the Natural Heritage reporting form provided at the end of this publication. The New York Natural Heritage Program is a partnership with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and by The Nature Conservancy. Major support comes from the NYS Biodiversity Research Institute, the Environmental Protection Fund, and Return a Gift to Wildlife. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... Page ii Why is the list published? What does the list contain? How is the information compiled? How does the list change? Why are plants rare? Why protect rare plants? Explanation of categories.................................................................................................................... Page iv Explanation of Heritage ranks and codes............................................................................................ Page iv Global rank State rank Taxon rank Double ranks Explanation of plant -

Lquat Arctic Alpine Plants

The Late -Quaternary History of Arctic and Alpine Plants and their future in a warming world Hilary H. Birks University of Bergen How do we reconstruct the history of flora and vegetation? Where do we find our evidence and how do we interpret it? The history of the history What were past climates like and how did they change? How did plants survive climate change? The most recent glacial climate – the Younger Dryas How did arctic and alpine plants react to Holocene warming? What does the future hold for Arctic and Alpine plants? 1 1. Evidence of past flora and its changes Fossils • Pollen - microscopic • Macrofossils – can be seen with naked eye. Seeds, fruits, leaves, etc. Molecular DNA analyses of living arctic alpines can complement the fossil record. Find different populations in space today and deduce past migrations Fossil DNA extraction from sediments or plant remains is becoming increasingly sophisticated Pollen grains and spores • Walls are sporopollenin, very resistant to decay • Preserve well in anaerobic environments, e.g. lake sediments, peats • Can be extracted from the sediment matrix using chemicals to remove the organic and inorganic sediment components • Counted under a high-power microscope • Frequent enough to allow percentage calculations of abundance 2 BUT - in glacial and late-glacial environments: • Wind-dispersed pollen types dominate the assemblages (grasses, sedges, Artemisia ) • Arctic and alpine herbs generally produce rather little pollen • They are frequently insect pollinated • In landscapes with plants -

GRANITIC FLATROCK (ANNUAL HERB SUBTYPE) Concept: Granitic

GRANITIC FLATROCK (ANNUAL HERB SUBTYPE) Concept: Granitic Flatrock communities are sparsely vegetated or herbaceous communities of flatrock outcrops. The Annual Herb Subtype represents the zones in the vegetation mosaic that occur on the shallowest soil accumulations or on bare rock, where plants are primarily annual herbs, small bryophytes, or lichens. This subtype represents the earliest stages of primary succession. Characteristic flatrock endemic species such as Diamorpha smalli, Sedum pusillum, Portulaca smallii, Mononeuria uniflora, and Cyperus granitophilus occur primarily in this subtype. Distinguishing Features: Granitic Flatrocks are distinguished from Granitic Domes by floristic differences such as the presence of Diamorpha smallii, Sedum pusillum, Mononeuria glabra, Packera tomentosa, Croton willdenowii, and the absence of plants more characteristic of the Blue Ridge, as well as by their location in the central and eastern Piedmont. They are generally distinguished by gentler topography and the associated presence of small weathering depressions, but the range of slopes can overlap with that of Granitic Domes. Granitic Flatrocks are distinguished from all other rock outcrop communities by the characteristic physical structure produced by exfoliation, with shallow depressions but few crevices, fractures, or deeper soil pockets. The Annual Herb Subtype is distinguished from other zones by the dominance of smaller mosses, lichens, or annual herbs, usually Diamorpha, Mononeuria, Sedum, or Portulaca, but also including Hexasepalum (Diodia) teres, Cyperus granitophilus, Hypericum gentianoides, and others. Mats of Grimmia laevigata are included, but beds of Polytrichum spp., Sphagnum spp. beds in seeps, and other larger mosses are included with the Perennial Herb Subtype. Synonyms: Diamorpha smallii - Minuartia glabra - Minuartia uniflora - Cyperus granitophilus Herbaceous Vegetation (CEGL004344). -

Kimberly Norton Taylor1 and Dwayne Estes

The floristic and community ecology of seasonally wet limestone glade seeps of Tennessee and Kentucky Kimberly Norton Taylor1 and Dwayne Estes Austin Peay State University Department of Biology and Center of Excellence for Field Biology Clarksville, Tennessee 37044, U.S.A. [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT An open, seasonally wet seep community supporting herbaceous vegetation occurs within the limestone cedar glade complex of the southeastern United States. The purpose of this study is to describe the floristic composition of these limestone glade seeps. A floristic inventory of 9 season- ally wet sites in central Tennessee and south-central Kentucky was performed, documenting 114 species and infraspecific taxa in 91 genera and 43 families. Vegetation analysis identified the dominant taxa as Eleocharis bifida (% IV 20.3), Sporobolus vaginiflorus (% IV 11.94), Hypericum sphaerocarpum (% IV 5.97), Allium aff. stellatum (% IV 4.71), Clinopodium glabellum/arkansanum (% IV 4.15), Schoenolirion croceum (% IV 3.89), Juncus filipendulus (% IV 3.89), and Carex crawei (% IV 3.84). Gratiola quartermaniae and Isoëtes butleri are also important members of the community and may serve as indicator species. A wetland assessment of the seep community was performed according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Wetland Delineation Manual and appropriate regional supplements. Wetland vegetation requirements are satisfied in 8 of the 9 seasonally wet sites sampled. The limestone glade seeps appear to represent a previously unclassified seasonal wetland type. RESUMEN Una comunidad abierta, húmeda estacionalmente por filtración, compuesta por vegetación herbácea se da en el complejo de pantanos cal- cáreos de cedro del sureste de los Estados Unidos. -

Literature Cited Allendorf, F. W. and G. Luikart. 2007. Conservation and the Genetics of Populations. Blackwell Publishing, Ma

Literature Cited Allendorf, F. W. and G. Luikart. 2007. Conservation and the Genetics of Populations. Blackwell Publishing, Malden, Massachusetts. 642 pp. Chester, E. W., B. E. Wofford, D. Estes, and C. Bailey. 2009. A Fifth Checklist of Tennessee Vascular Plants. Botanical Research Institute of Texas Press, Fort Worth, Texas. 102 pp. Dell, N. 2018. Email to Geoff Call, Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service re: Mononeuria (=Minuartia) cumberlandensis accessions at Missouri Botanical Garden. Center for Conservation and Sustainable Development, Missouri Botanical Garden, April 25, 2018. Dillenberger, M. S. and J. W. Kadereit. 2014. Multiple origins and delimitation with plesiomorphic characters require a new circumscription of Minuartia (Caryophyllaceae). Taxon 63:64-88. Flora of North America. 2019. http://www.efloras.org. Accessed February 5, 2019. Glick, P., S. Palmer, and J. Wisby. 2015. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment for Tennessee Wildlife and Habitats. Prepared by National Wildlife Federation and The Nature Conservancy—Tennessee for Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, Nashville, Tennessee. 104 pp. Henderson, C. P. 2018. Email to Geoff Call, Biologist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service re: TennGreen easements near Big South Fork – Peters Bridge. Director of Land Conservation, Tennessee Parks and Greenways Foundation, May 1, 2018. Heschel, M. S. and K. N. Paige. 1995. Inbreeding depression, environmental stress, and population size variation in scarlet gilia (Ipomopsis aggregata). Conservation Biology 9:126-133. Horton, J. D., 2017. The State Geologic Map Compilation (SGMC) geodatabase of the conterminous United States (ver. 1.1, August 2017): U.S. Geological Survey data release, https://doi.org/10.5066/F7WH2N65. Integrated Taxonomic Information System. -

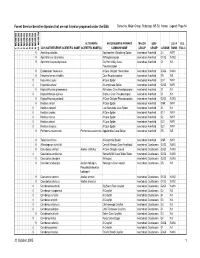

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR