Tuning Supplement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

Music in the Mid-Fifteenth Century 1440–1480

21M.220 Fall 2010 Class 13 BRIDGE 2: THE RENAISSANCE PART 1: THE MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY 1. THE ARMED MAN! 2. Papers and revisions 3. The (possible?) English Influence a. Martin le Franc ca. 1440 and the contenance angloise b. What does it mean? c. 6–3 sonorities, or how to make fauxbourdon d. Dunstaple (Dunstable) (ca. 1390–1453) as new creator 4. Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) (ca. 1397–1474) and his music a. Roughly 100 years after Guillaume de Machaut b. Isorhythmic motets i. Often called anachronistic, but only from the French standpoint ii. Nuper rosarum flores iii. Dedication of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de’ Fiore in Florence iv. Structure of the motet is the structure of the cathedral in Florence v. IS IT? Let’s find out! (Tape measures) c. Polyphonic Mass Cycle i. First flowering—Mass of Machaut is almost a fluke! ii. Cycle: Five movements from the ordinary, unified somehow iii. Unification via preexisting materials: several types: 1. Contrafactum: new text, old music 2. Parody: take a secular song and reuse bits here and there (Zachara) 3. Cantus Firmus: use a monophonic song (or chant) and make it the tenor (now the second voice from the bottom) in very slow note values 4. Paraphrase: use a song or chant at full speed but change it as need be. iv. Du Fay’s cantus firmus Masses 1. From late in his life 2. Missa L’homme armé a. based on a monophonic song of unknown origin and unknown meaning b. Possibly related to the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded in 1430. -

A History of British Music Vol 1

A History of Music in the British Isles Volume 1 A History of Music in the British Isles Other books from e Letterworth Press by Laurence Bristow-Smith e second volume of A History of Music in the British Isles: Volume 1 Empire and Aerwards and Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History From Monks to Merchants Laurence Bristow-Smith The Letterworth Press Published in Switzerland by the Letterworth Press http://www.eLetterworthPress.org Printed by Ingram Spark To © Laurence Bristow-Smith 2017 Peter Winnington editor and friend for forty years ISBN 978-2-9700654-6-3 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Contents Acknowledgements xi Preface xiii 1 Very Early Music 1 2 Romans, Druids, and Bards 6 3 Anglo-Saxons, Celts, and Harps 3 4 Augustine, Plainsong, and Vikings 16 5 Organum, Notation, and Organs 21 6 Normans, Cathedrals, and Giraldus Cambrensis 26 7 e Chapel Royal, Medieval Lyrics, and the Waits 31 8 Minstrels, Troubadours, and Courtly Love 37 9 e Morris, and the Ballad 44 10 Music, Science, and Politics 50 11 Dunstable, and la Contenance Angloise 53 12 e Eton Choirbook, and the Early Tudors 58 13 Pre-Reformation Ireland, Wales, and Scotland 66 14 Robert Carver, and the Scottish Reformation 70 15 e English Reformation, Merbecke, and Tye 75 16 John Taverner 82 17 John Sheppard 87 18 omas Tallis 91 19 Early Byrd 101 20 Catholic Byrd 108 21 Madrigals 114 22 e Waits, and the eatre 124 23 Folk Music, Ravenscro, and Ballads 130 24 e English Ayre, and omas Campion 136 25 John Dowland 143 26 King James, King Charles, and the Masque 153 27 Orlando Gibbons 162 28 omas -

T 2021-2022 Season

Tickets & Season-Ticket Packages gathering again Tickets are available at the door, payable with cash, February 23, 2020. check, or credit card: $30 general, $25 senior (age 60+). That was the date of our final, in-person performance You can also visit www.early-music.org for season- before the “long intermission.” That was the last time ticket packages, single concert tickets, or donations. we were able to gather—performers, audience, and Season-ticket packages can also be purchased using the crew—all in the same space. Since then, we have order form on this brochure, payable by cash, check, or had many hours (~180) of recording, one or two credit card. Discounted tickets for students with ID are people at a time, in an effort to keep each other as safe available for purchase at the concert door for $5. as possible. Those mini gatherings were joyful celebrations, providing a fleeting but necessary sense Special Services for Season-Ticket Holders of normalcy. When we are next able to fully assemble Bring a Guest: Each season-ticket holder will receive our company again with you, our audience, it will have been more than 19 months since the last time! one free ticket for ONE guest at ONE concert of choice, An Early Christmas excluded. However, you must Gathering again will help us all regain a feeling of contact us at least 5 days in advance of the concert to rediscovery of a missing treasure, our friends, and our reserve a seat for your friend guest. Call 512-377-6961 TEMP community. -

Phonographic Bulletin

iasa International Association of Sound Archives Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores Internation~le Vereinigun~ 'd,er,Schallarchive phonographic bulletin no.29/March 1981 PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN Journal of the International Association of Sound Archives IASA Organe de 1 'Association Internationale d'Archives Sonores IASA Zeitschrift der Internationalen Vereinigung der Schallarchive IASA Associate Editors: Ann Briegleb, Ethnomusiocology Archives, UCLA, Los Angeles; Frank J. Gillis, Archives of Traditional Music, Indiana University, B1oomington. Technical Editor: Dr. Dietrich SchUller, Phonograrrunarchiv der Oesterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien. The PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN is published three times a year and is sent to all members of IASA. Applications for membership in IASA should be sent to the Secretary (see list of officers be low). The annual dues are at the moment 25.-Deutsche Mark for individual members and 60. Deutsche Mark for institutional members. Back copies of the PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN from 1971 are available at 15.-Deutsche Mark for each year's issue, including postage. Subscriptions to the current year's issues of the PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN are also available to non-members at a cost of 25.-Deutsche Mark. Le journal de 1 'Association internationale d'archives sonores, le PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN, est publie trois fois 1 'an et distribue a tous les membres. Veuillez envoyer vos demandes d'adhesion au \secretaire dont vous trouverez 1 'adresse ci-dessous. Les cotisations annuel1es sont en ce . moment de 25.-Deutsche Mark pour les membres individuels et 60.-Deutsche Mark pour les membres . institutionne1s. Les numeros precedents (a partir de 1971) du PHONOGRAPHIC BULLETIN sont dis ponibles au cout de 15.-Deutsche Mark par annee (frais de port inclus). -

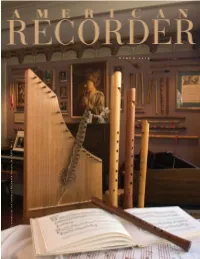

M a R C H 2 0

march 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Order your recorder discs through the ARS CD Club! The ARS CD Club makes hard-to-find or limited release CDs by ARS members available to ARS members at the special price listed (non-members slightly higher). Add Shipping and Handling:: $2 for one CD, $1 for each additional CD. An updated listing of all available CDs may be found at the ARS web site: <www.americanrecorder.org>. NEW LISTING! ____THE GREAT MR. HANDEL Carolina Baroque, ____LUDWIG SENFL Farallon Recorder Quartet Dale Higbee, recorders. Sacred and secular music featuring Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, Louise by Handel. Live recording. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____HANDEL: THE ITALIAN YEARS Elissa Carslake and Hanneke van Proosdij. 23 lieder, ____SOLO, Berardi, recorder & Baroque flute; Philomel motets and instrumental works of the German DOUBLE & Baroque Orchestra. Handel, Nel dolce dell’oblio & Renaissance composer. TRIPLE CONCER- Tra le fiamme, two important pieces for obbligato TOS OF BACH & TELEMANN recorder & soprano; Telemann, Trio in F; Vivaldi, IN STOCK (Partial listing) Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee, recorders. All’ombra di sospetto. Dorian. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____ARCHIPELAGO Alison Melville, recorder & 2-CD set, recorded live. $24 ARS/$28 others. traverso. Sonatas & concerti by Hotteterre, Stanley, ____JOURNEY Wood’N’Flutes, Vicki Boeckman, ____SONGS IN THE GROUND Cléa Galhano, Bach, Boismortier and others. $15 ARS/$17 Others. Gertie Johnsson & Pia Brinch Jensen, recorders. recorder, Vivian Montgomery, harpsichord. Songs ____ARLECCHINO: SONATAS AND BALLETTI Works by Dufay, Machaut, Henry VIII, Mogens based on grounds by Pandolfi, Belanzanni, Vitali, OF J. -

Music of the Burgundians

2015-2016 he Sounds of Time Music of the Burgundians TENET Jolle Greenleaf soprano Virginia Warnken Kelsey alto Jason McStoots tenor Andrew Padgett bass Robert Mealy vielle Dongmyung Ahn vielle Priscilla Herreid winds Jolle Greenleaf artistic director Robert Mealy guest music director 7pm on Friday, May 20, 2016 Saint Peter’s Church 619 Lexington Avenue New York City Music of the Burgundians (In memory of Richard Steinman) Donnés l’assault Guillaume Du Fay (1397–1474) De plus en plus se renouvelle Gilles Binchois (c. 1400–1460) La Danse de Clèves Anonymous, from Bruxelles MS 9085 Margarite, fleur de valeur Du Fay Je veuil chanter Du Fay Je ne vis oncques Binchois/Du Fay Je me recommande humblement Binchois Basse danse La Franchoise nouvelle Anonymous Mon cuer me fait dis penser Du Fay Plains de ploure Binchois Je me complains Du Fay Malhereux cueur Du Fay Dueil angoisseus Binchois Je demande ma bienvenue Johannes Haucourt (fl. c. 1390–c. 1416) Je ne puis vivre Antoine Busnoys (c. 1430–1492) De tous bien playne Hayne van Ghizeghem (c1445–1477) Josquin des Prez (c.1450–1521) Vostre beauté / vous marches Busnoys 3 Rabbit hunting with ferrets, Franco-Flemish, 1460 4 TEXT AND TRANSLATIONS Donnés l’assault a la fortresse Assault the fortress De ma gratieuse maistresse, of my gracious mistress, Hault dieu d’amors, je vous supplye; High god of Love, I beg of you. Boutés hors m’adverse partie Throw forth my enemy Qui languir me fait en destresse. who makes me languish in distress. C’est d’Anuy, qui par sa rudesse It is that of Spite, who, in his harshness De moy grever point ne se cesse never ceases to torment me my sweet and re- Envers ma dame gente et lye. -

Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European Musical

Ch. 4: Island and Mainland: Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European musical style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries moved from distinct national styles (particularly of the Ars nova and Trecento) toward a more unified, international style. II. English Music and Its Influence A. Fragmentary Remains 1. English music had a style that was distinct from continental music of the Middle Ages. 2. English singers included the third among the consonant intervals. 3. The Thomas gemma Cantuariae/Thomas caesus in Doveria (Ex. 4-3) includes many features associated with English music, such as almost equal ranges in the top two parts and frequent voice exchanges. B. Kings and the Fortunes of War 1. The Old Hall Manuscript contains the earliest English polyphonic church music that can be read today. 2. Copied for a member of the royal family, most of its contents belong to the Mass Ordinary. 3. Henry V, who is associated with the Old Hall Manuscript, holds a prominent place in history of this period. 4. When Henry’s army occupied part of northern France in the early fifteenth century, his brother John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, was in charge. This brother included the composer John Dunstable (ca. 1390–1453) among those who received part of his estates when he died. 5. Dunstable’s music influenced continental composers. C. Dunstable and the “Contenance Angloise” 1. Dunstable’s arrival in Paris caused the major composers to follow his style, known as la contenance angloise. a. Major-mode tonality b. Triadic harmony c. Smooth handling of dissonance 2. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

B.A.Western Music School of Music and Fine Arts

B.A.Western Music Curriculum and Syllabus (Based on Choice based Credit System) Effective from the Academic Year 2018-2019 School of Music and Fine Arts PROGRAM EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES (PEO) PEO1: Learn the fundamentals of the performance aspect of Western Classical Karnatic Music from the basics to an advanced level in a gradual manner. PEO2: Learn the theoretical concepts of Western Classical music simultaneously along with honing practical skill PEO3: Understand the historical evolution of Western Classical music through the various eras. PEO4: Develop an inquisitive mind to pursue further higher study and research in the field of Classical Art and publish research findings and innovations in seminars and journals. PEO5: Develop analytical, critical and innovative thinking skills, leadership qualities, and good attitude well prepared for lifelong learning and service to World Culture and Heritage. PROGRAM OUTCOME (PO) PO1: Understanding essentials of a performing art: Learning the rudiments of a Classical art and the various elements that go into the presentation of such an art. PO2: Developing theoretical knowledge: Learning the theory that goes behind the practice of a performing art supplements the learner to become a holistic practioner. PO3: Learning History and Culture: The contribution and patronage of various establishments, the background and evolution of Art. PO4: Allied Art forms: An overview of allied fields of art and exposure to World Music. PO5: Modern trends: Understanding the modern trends in Classical Arts and the contribution of revolutionaries of this century. PO6: Contribution to society: Applying knowledge learnt to teach students of future generations . PO7: Research and Further study: Encouraging further study and research into the field of Classical Art with focus on interdisciplinary study impacting society at large. -

Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century

David Fallows Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century VARIORUM 1996 CONTENTS Preface vn Acknowledgements V1H ENGLAND English song repertories of the mid-fifteenth century 61-79 Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 103. London, 1976-77 II Robertus de Anglia and the Oporto song collection 99-128 Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music: A Memorial Volume to Thurston Dart, ed. Ian Bent. London: Stabler & Bell Ltd, 1981 III Review of Julia Boffey: Manuscripts of English Courtly Love Lyrics in the later Middle Ages 132-138 Journal of the Royal Musical Association 112. Oxford, 1987 IV Dunstable, Bedyngham and O rosa be I la 287-305 The Journal of Musicology 12. Berkeley, Calif, 1994 MAINLAND EUROPE The contenance angloise: English influence on continental composers of the fifteenth century 189-208 Renaissance Studies 1. Oxford, 1987 VI French as a courtly language in fifteenth-century Italy: the musical evidence 429-441 Renaissance Studies 3. Oxford, 1989 VI VII A glimpse of the lost years: Spanish polyphonic song, 1450-70 19-36 New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern, ed. Josephine Wright with Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music. Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1992 VIII Polyphonic song in the Florence of Lorenzo's youth, ossia: the provenance of the manuscript Berlin 78.C.28: Naples or Florence? 47-61 La musica a Firenze at tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, ed. Piero Gargiulo. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1993 IX Prenez sur moy: Okeghem's tonal pun 63-75 Plainsong and Medieval Music 1. -

Dictionary of Music.Pdf

The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music The FACTS ON FILE Dictionary of Music Christine Ammer The Facts On File Dictionary of Music, Fourth Edition Copyright © 2004 by the Christine Ammer 1992 Trust All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ammer, Christine The Facts On File dictionary of music / Christine Ammer.—4th ed. p. cm. Includes index. Rev. ed. of: The HarperCollins dictionary of music. 3rd ed. c1995. ISBN 0-8160-5266-2 (Facts On File : alk paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3009-5 (e-book) 1. Music—Dictionaries. 2. Music—Bio-bibliography. I. Title: Dictionary of music. II. Ammer, Christine. HarperCollins dictionary of music. III. Facts On File, Inc. IV. Title. ML100.A48 2004 780'.3—dc22 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by James Scotto-Lavino Cover design by Semadar Megged Illustrations by Carmela M. Ciampa and Kenneth L. Donlan Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint an excerpt from Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise.” Copyright © 1960 Hinrichsen Edition, Peters Edition Limited, London.