La Contenance Angloise: Nathaniel Lanasa, Conducting Apprentice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

Music in the Mid-Fifteenth Century 1440–1480

21M.220 Fall 2010 Class 13 BRIDGE 2: THE RENAISSANCE PART 1: THE MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY 1. THE ARMED MAN! 2. Papers and revisions 3. The (possible?) English Influence a. Martin le Franc ca. 1440 and the contenance angloise b. What does it mean? c. 6–3 sonorities, or how to make fauxbourdon d. Dunstaple (Dunstable) (ca. 1390–1453) as new creator 4. Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) (ca. 1397–1474) and his music a. Roughly 100 years after Guillaume de Machaut b. Isorhythmic motets i. Often called anachronistic, but only from the French standpoint ii. Nuper rosarum flores iii. Dedication of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de’ Fiore in Florence iv. Structure of the motet is the structure of the cathedral in Florence v. IS IT? Let’s find out! (Tape measures) c. Polyphonic Mass Cycle i. First flowering—Mass of Machaut is almost a fluke! ii. Cycle: Five movements from the ordinary, unified somehow iii. Unification via preexisting materials: several types: 1. Contrafactum: new text, old music 2. Parody: take a secular song and reuse bits here and there (Zachara) 3. Cantus Firmus: use a monophonic song (or chant) and make it the tenor (now the second voice from the bottom) in very slow note values 4. Paraphrase: use a song or chant at full speed but change it as need be. iv. Du Fay’s cantus firmus Masses 1. From late in his life 2. Missa L’homme armé a. based on a monophonic song of unknown origin and unknown meaning b. Possibly related to the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded in 1430. -

A History of British Music Vol 1

A History of Music in the British Isles Volume 1 A History of Music in the British Isles Other books from e Letterworth Press by Laurence Bristow-Smith e second volume of A History of Music in the British Isles: Volume 1 Empire and Aerwards and Harold Nicolson: Half-an-Eye on History From Monks to Merchants Laurence Bristow-Smith The Letterworth Press Published in Switzerland by the Letterworth Press http://www.eLetterworthPress.org Printed by Ingram Spark To © Laurence Bristow-Smith 2017 Peter Winnington editor and friend for forty years ISBN 978-2-9700654-6-3 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Contents Acknowledgements xi Preface xiii 1 Very Early Music 1 2 Romans, Druids, and Bards 6 3 Anglo-Saxons, Celts, and Harps 3 4 Augustine, Plainsong, and Vikings 16 5 Organum, Notation, and Organs 21 6 Normans, Cathedrals, and Giraldus Cambrensis 26 7 e Chapel Royal, Medieval Lyrics, and the Waits 31 8 Minstrels, Troubadours, and Courtly Love 37 9 e Morris, and the Ballad 44 10 Music, Science, and Politics 50 11 Dunstable, and la Contenance Angloise 53 12 e Eton Choirbook, and the Early Tudors 58 13 Pre-Reformation Ireland, Wales, and Scotland 66 14 Robert Carver, and the Scottish Reformation 70 15 e English Reformation, Merbecke, and Tye 75 16 John Taverner 82 17 John Sheppard 87 18 omas Tallis 91 19 Early Byrd 101 20 Catholic Byrd 108 21 Madrigals 114 22 e Waits, and the eatre 124 23 Folk Music, Ravenscro, and Ballads 130 24 e English Ayre, and omas Campion 136 25 John Dowland 143 26 King James, King Charles, and the Masque 153 27 Orlando Gibbons 162 28 omas -

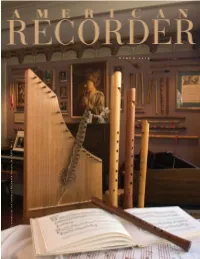

M a R C H 2 0

march 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Order your recorder discs through the ARS CD Club! The ARS CD Club makes hard-to-find or limited release CDs by ARS members available to ARS members at the special price listed (non-members slightly higher). Add Shipping and Handling:: $2 for one CD, $1 for each additional CD. An updated listing of all available CDs may be found at the ARS web site: <www.americanrecorder.org>. NEW LISTING! ____THE GREAT MR. HANDEL Carolina Baroque, ____LUDWIG SENFL Farallon Recorder Quartet Dale Higbee, recorders. Sacred and secular music featuring Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, Louise by Handel. Live recording. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____HANDEL: THE ITALIAN YEARS Elissa Carslake and Hanneke van Proosdij. 23 lieder, ____SOLO, Berardi, recorder & Baroque flute; Philomel motets and instrumental works of the German DOUBLE & Baroque Orchestra. Handel, Nel dolce dell’oblio & Renaissance composer. TRIPLE CONCER- Tra le fiamme, two important pieces for obbligato TOS OF BACH & TELEMANN recorder & soprano; Telemann, Trio in F; Vivaldi, IN STOCK (Partial listing) Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee, recorders. All’ombra di sospetto. Dorian. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____ARCHIPELAGO Alison Melville, recorder & 2-CD set, recorded live. $24 ARS/$28 others. traverso. Sonatas & concerti by Hotteterre, Stanley, ____JOURNEY Wood’N’Flutes, Vicki Boeckman, ____SONGS IN THE GROUND Cléa Galhano, Bach, Boismortier and others. $15 ARS/$17 Others. Gertie Johnsson & Pia Brinch Jensen, recorders. recorder, Vivian Montgomery, harpsichord. Songs ____ARLECCHINO: SONATAS AND BALLETTI Works by Dufay, Machaut, Henry VIII, Mogens based on grounds by Pandolfi, Belanzanni, Vitali, OF J. -

Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European Musical

Ch. 4: Island and Mainland: Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European musical style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries moved from distinct national styles (particularly of the Ars nova and Trecento) toward a more unified, international style. II. English Music and Its Influence A. Fragmentary Remains 1. English music had a style that was distinct from continental music of the Middle Ages. 2. English singers included the third among the consonant intervals. 3. The Thomas gemma Cantuariae/Thomas caesus in Doveria (Ex. 4-3) includes many features associated with English music, such as almost equal ranges in the top two parts and frequent voice exchanges. B. Kings and the Fortunes of War 1. The Old Hall Manuscript contains the earliest English polyphonic church music that can be read today. 2. Copied for a member of the royal family, most of its contents belong to the Mass Ordinary. 3. Henry V, who is associated with the Old Hall Manuscript, holds a prominent place in history of this period. 4. When Henry’s army occupied part of northern France in the early fifteenth century, his brother John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, was in charge. This brother included the composer John Dunstable (ca. 1390–1453) among those who received part of his estates when he died. 5. Dunstable’s music influenced continental composers. C. Dunstable and the “Contenance Angloise” 1. Dunstable’s arrival in Paris caused the major composers to follow his style, known as la contenance angloise. a. Major-mode tonality b. Triadic harmony c. Smooth handling of dissonance 2. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century

David Fallows Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century VARIORUM 1996 CONTENTS Preface vn Acknowledgements V1H ENGLAND English song repertories of the mid-fifteenth century 61-79 Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 103. London, 1976-77 II Robertus de Anglia and the Oporto song collection 99-128 Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music: A Memorial Volume to Thurston Dart, ed. Ian Bent. London: Stabler & Bell Ltd, 1981 III Review of Julia Boffey: Manuscripts of English Courtly Love Lyrics in the later Middle Ages 132-138 Journal of the Royal Musical Association 112. Oxford, 1987 IV Dunstable, Bedyngham and O rosa be I la 287-305 The Journal of Musicology 12. Berkeley, Calif, 1994 MAINLAND EUROPE The contenance angloise: English influence on continental composers of the fifteenth century 189-208 Renaissance Studies 1. Oxford, 1987 VI French as a courtly language in fifteenth-century Italy: the musical evidence 429-441 Renaissance Studies 3. Oxford, 1989 VI VII A glimpse of the lost years: Spanish polyphonic song, 1450-70 19-36 New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern, ed. Josephine Wright with Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music. Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1992 VIII Polyphonic song in the Florence of Lorenzo's youth, ossia: the provenance of the manuscript Berlin 78.C.28: Naples or Florence? 47-61 La musica a Firenze at tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, ed. Piero Gargiulo. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1993 IX Prenez sur moy: Okeghem's tonal pun 63-75 Plainsong and Medieval Music 1. -

Věra Oščádalová BRITISH CHORAL TRADITION with an EMPHASIS

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglického jazyka Věra Oščádalová III. ročník – prezenční studium Obor: Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání – Hudební kultura se zaměřením na vzdělávání BRITISH CHORAL TRADITION WITH AN EMPHASIS ON BENJAMIN BRITTEN’S WORK Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Světlana Obenausová, MLitt, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci vypracovala samostatně a výhradně za použití uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci 23. 4. 2014 ……………………………………………… vlastnoruční podpis I would like to thank PhDr. Světlana Obenausová, MLitt, Ph.D. for her support and valuable comments on the content and style of my final project. CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ABSTRACT Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 7 British Choral Tradition ...................................................................................................... 9 1 History .......................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Earliest British vocal and choral music ................................................................... 10 1.3 Renaissance ............................................................................................................. 12 1.4 Golden Age ............................................................................................................. 14 1.5 Baroque .................................................................................................................. -

Improvisation: Performer As Co-Composer

Musical Offerings Volume 3 Number 1 Spring 2012 Article 3 2012 Improvisation: Performer as Co-composer Kyle Schick Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Schick, Kyle (2012) "Improvisation: Performer as Co-composer," Musical Offerings: Vol. 3 : No. 1 , Article 3. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2012.3.1.3 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol3/iss1/3 Improvisation: Performer as Co-composer Document Type Article Abstract Elements of musical improvisation have been present throughout the medieval, renaissance, and baroque eras, however, improvisation had the most profound recorded presence in the baroque era. Improvisation is inherently a living practice and leaves little documentation behind for historians to study, but however elusive, it is still important to trace where instances of this improvised art appear throughout the eras listed above. It is also interesting to trace what role improvisation would later have in realizing the Baroque ideals of emotional expression, virtuosity, and individuality. This paper seeks to focus on a few of the best documented mediums of improvisation within each era. -

N O V E M B E R 2 0

november 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 5 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published The world’s most dependable and chosen recorders are also the most playful that students are sure to enjoy. Sour Apple Green, Cotton Candy Blue and Bubble Gum Pink colors add that extra fun for students beginning their music education. Yamaha 20 Series Recorders are specially designed for beginning students and are easy to play in every range. They offer the ideal amount of air resistance for effortless control and an accuracy of intonation that provides a rich, full sound. Playful with serious quality Yamaha is known for, Yamaha Recorders are the thoughtful choice for teachers that care. ©2005 Yamaha Corporation of America www.yamaha.com EDITOR’S ______NOTE ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume XLVI, Number 5 November 2005 confess that one of my weaknesses is FEATURES Imass market paperback mysteries, A Posthumous Approach to the Baroque Masters . 8 which a local used bookstore sells at eight Sei Soli per Flauto senza Basso, for $5. The thought threshold required to by Matthias Maute read them is minimal enough that one mystery usually equals an evening or It’s Summertime . 15 weekend of pleasurable distraction. 4 Matthias Maute rethinks the Role of the Recorder, I usually look for authors I know can by Jen Hoyer write in an interesting style and can devise a clever plot—Stuart Kaminsky, Tony Cultivating the Graces on the Greens. 18 Hillerman and others writing geographical Developing a Family Program, mysteries, Victorian-set tales from Anne by Rebecca Arkenberg Perry, Ngaio Marsh, Ruth Rendell. -

Syllabus 251 Fall 041 2

Fall, 2004, meets TR 2:30-3:45 Prof. Hamessley Office hours: TR 10:30-11:30 204 List, 859-4354; e-mail: lhamessl Music 251W Music in Europe Before 1600 Objectives: The primary goal of this course is to familiarize you with the major developments in musical styles and genres during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Besides the consideration of the theory and specific musical genres of the time, the course will include an examination of the political, economic, and cultural environments that influenced the musical practices of those eras. Required Texts and Materials: You must buy the following texts; however, copies may be on reserve (with the exception of the study guide, which you MUST purchase right away). Barbara Russano Hanning, Concise History of Western Music, 2nd ed. [CHWM] Claude V. Palisca, Norton Anthology of Western Music, v. 1, 4th ed. [NAWM] — scores. J. Peter Burkholder, Study and Listening Guide, 2nd ed. Richard J. Wingell, Writing About Music: An Introductory Guide, 3rd ed. Diana Hacker, A Pocket Style Manual, 3rd ed. You must have an e-mail account. Announcements will be made via e-mail and Blackboard on the web. Bring CHWM and NAWM to each class meeting. Recommended Materials: Although copies of the following CDs will be on reserve, you may choose to buy them at the bookstore. Students find it quite useful to have the musical examples in their room for study when the library is closed. However, there will be listening examples drawn from many other recordings as well, so you will still need to plan listening/study time in the Music Library. -

Tuning Supplement

TUNING SUPPLEMENT PETER GREENHILL 2017 This supplement is prompted by some major developments in the understanding of cerdd dant composition that have occurred in the years since my ‘Tuning’ dissertation was written.1 That dissertation drew confident conclusions as to the identity of the nominal pitches the harp was tuned to in order to perform the pieces intablated in the Robert ap Huw manuscript. Numerous strong arguments were presented against the hypothesis that the diagrams on pp. 108-9 of the manuscript are scordatura tunings2 and the viability was demonstrated of each of the tablature letters referring to its literal written nominal pitch – i.e. all natural notes apart from B-flat – rather than to an unwritten and unidentified substitute nominal pitch.3 Subsequently, the cerdd dant scholar Paul Whittaker has taken care to guide the reader through illustrations of exactly how my tuning interpretation makes artistic and historical sense of the harmony and the melodic phrasing, using the clymau cytgerdd, Caniad Cadwgan and Caniad Cynwrig Bencerdd as examples, on pages 11-16 of his deeply-probing article: ‘Harmonic Forms in the Robert ap Huw Manuscript’,4 and Paul Dooley and I have aired my translations of the manuscript, in illustration of the melodic and harmonic comprehensibility of the nominal pitch solution when set into the historical context 1 Peter Greenhill, ‘The Robert ap Huw Manuscript: an exploration of its possible solutions’, 3: ‘Tuning’ (2000), CAWMS dissertation, Bangor University, <http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/musicfiles/manuscripts/aphuw/aphuw-t.pdf>. 2 ibid., pp. 33-52. 3 ibid., pp.