A History of British Music Vol 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guillaume Du Fay Discography

Guillaume Du Fay Discography Compiled by Jerome F. Weber This discography of Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) builds on the work published in Fanfare in January and March 1980. There are more than three times as many entries in the updated version. It has been published in recognition of the publication of Guillaume Du Fay, his Life and Works by Alejandro Enrique Planchart (Cambridge, 2018) and the forthcoming two-volume Du Fay’s Legacy in Chant across Five Centuries: Recollecting the Virgin Mary in Music in Northwest Europe by Barbara Haggh-Huglo, as well as the new Opera Omnia edited by Planchart (Santa Barbara, Marisol Press, 2008–14). Works are identified following Planchart’s Opera Omnia for the most part. Listings are alphabetical by title in parts III and IV; complete Masses are chronological and Mass movements are schematic. They are grouped as follows: I. Masses II. Mass Movements and Propers III. Other Sacred Works IV. Songs (Italian, French) Secular works are identified as rondeau (r), ballade (b) and virelai (v). Dubious or unauthentic works are italicised. The recordings of each work are arranged chronologically, citing conductor, ensemble, date of recording if known, and timing if available; then the format of the recording (78, 45, LP, LP quad, MC, CD, SACD), the label, and the issue number(s). Each recorded performance is indicated, if known, as: with instruments, no instruments (n/i), or instrumental only. Album titles of mixed collections are added. ‘Se la face ay pale’ is divided into three groups, and the two transcriptions of the song in the Buxheimer Orgelbuch are arbitrarily designated ‘a’ and ‘b’. -

Music in the Mid-Fifteenth Century 1440–1480

21M.220 Fall 2010 Class 13 BRIDGE 2: THE RENAISSANCE PART 1: THE MID-FIFTEENTH CENTURY 1. THE ARMED MAN! 2. Papers and revisions 3. The (possible?) English Influence a. Martin le Franc ca. 1440 and the contenance angloise b. What does it mean? c. 6–3 sonorities, or how to make fauxbourdon d. Dunstaple (Dunstable) (ca. 1390–1453) as new creator 4. Guillaume Du Fay (Dufay) (ca. 1397–1474) and his music a. Roughly 100 years after Guillaume de Machaut b. Isorhythmic motets i. Often called anachronistic, but only from the French standpoint ii. Nuper rosarum flores iii. Dedication of the Cathedral of Santa Maria de’ Fiore in Florence iv. Structure of the motet is the structure of the cathedral in Florence v. IS IT? Let’s find out! (Tape measures) c. Polyphonic Mass Cycle i. First flowering—Mass of Machaut is almost a fluke! ii. Cycle: Five movements from the ordinary, unified somehow iii. Unification via preexisting materials: several types: 1. Contrafactum: new text, old music 2. Parody: take a secular song and reuse bits here and there (Zachara) 3. Cantus Firmus: use a monophonic song (or chant) and make it the tenor (now the second voice from the bottom) in very slow note values 4. Paraphrase: use a song or chant at full speed but change it as need be. iv. Du Fay’s cantus firmus Masses 1. From late in his life 2. Missa L’homme armé a. based on a monophonic song of unknown origin and unknown meaning b. Possibly related to the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded in 1430. -

News from Around the Region Geraldine Elliott, Director North

Geraldine Elliott, Director North Central Region, AHS 753 Crestwood Dr. Waukesha, WI 53188 262.547.8539 [email protected] A tax-exempt non-profit corporation founded in 1962 Greetings to All Harpists in the North Central Region. I am honored to be your Regional Director at this exciting time in the life of the American Harp Society. Please let me know how I can facilitate communications between and among harpists in the Region. This Newsletter is one means of spreading the word among all the chapters in the Region, but it comes only once a year. There will be a second, email-only, message in the spring, so it is vitally important that we have accurate email addresses for all harpists. We send this newsletter to let you know about harp-happenings that are closer and less expensive (some are even free!) than the National meetings that are coming up. Please let me know of new items that arise so I can include them in the spring email blast. And donʼt forget to send me your accurate email address. THE AMERICAN HARP SOCIETY 9TH SUMMER INSTITUTE AND 19TH NATIONAL COMPETITION JUNE 19-23, 2011 THE LYON AND HEALY AWARDS JUNE 18-19, 2011 DENTON, TX (DALLAS/FT. WORTH AREA) WWW.MUSIC.UNT.EDU/HARP The University of North Texas welcomes the American Harp Society to enjoy a wonderful week. All events will be geared towards students and will include master classes, workshops, ensemble performances and viewing of historic harps. Performances will feature harpists of the Southwest and Emily Mitchell, guest artist and Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, the AHS Concert Artist, and Michael Colgrass will be guest clinician. -

Fomrhi-110.Pdf

v^uaneny INO. nu, iNovcmDer ^uuo FoMRHI Quarterly BULLETIN 110 Christopher Goodwin 2 COMMUNICATIONS 1815 On frets and barring; some useful ideas David E McConnell 5 1816 Modifications to recorder blocks to improve sound production Peter N Madge 9 1817 What is wrong with Vermeer's guitar Peter Forrester 20 1818 A new addition to the instruments of the Mary Rose Jeremy Montagu 24 181*9 Oud or lute? - a study J Downing 25 1820 Some parallels in the ancestry of the viol and violin Ephraim Segerman 30 1821 Notes on the polyphont Ephraim Segerman 31 1822 The 'English' in English violette Ephraim Segerman 34 1823 The identity of tlie lirone Ephraim Segerman 35 1824 On the origins of the tuning peg and some early instrument name:s E Segerman 36 1825 'Twined' strings for clavichords Peter Bavington 38 1826 Wood fit for a king? An investigation J Downing 43 1827 Temperaments for gut-strung and gut-fretted instruments John R Catch 48 1828 Reply to Hebbert's Comm. 1803 on early bending method Ephraim Segerman 58 1829 Reply to Peruffo's Comm. 1804 on gut strings Ephraim Segerman 59 1830 Reply to Downing's Comm. 1805 on silk/catgut Ephraim Segerman 71 1831 On stringing of lutes (Comm. 1807) and guitars (Comms 1797, 8) E Segerman 73 1832 Tapered lute strings and added mas C J Coakley 74 1833 Review: A History of the Lute from Antiquity to the Renaissance by Douglas Alton Smith (Lute Society of America, 2002) Ephraim Segerman 77 1834 Review: Die Renaissanceblockfloeten der Sammlung Alter Musikinstrumenten des Kunsthistorisches Museums (Vienna, 2006) Jan Bouterse 83 The next issue, Quarterly 111, will appear in February 2009. -

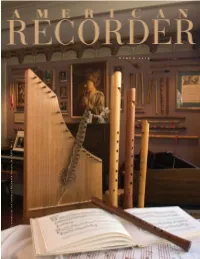

M a R C H 2 0

march 2005 Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. XLVI, No. 2 XLVI, Vol. American Recorder Society, by the Published Order your recorder discs through the ARS CD Club! The ARS CD Club makes hard-to-find or limited release CDs by ARS members available to ARS members at the special price listed (non-members slightly higher). Add Shipping and Handling:: $2 for one CD, $1 for each additional CD. An updated listing of all available CDs may be found at the ARS web site: <www.americanrecorder.org>. NEW LISTING! ____THE GREAT MR. HANDEL Carolina Baroque, ____LUDWIG SENFL Farallon Recorder Quartet Dale Higbee, recorders. Sacred and secular music featuring Letitia Berlin, Frances Blaker, Louise by Handel. Live recording. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____HANDEL: THE ITALIAN YEARS Elissa Carslake and Hanneke van Proosdij. 23 lieder, ____SOLO, Berardi, recorder & Baroque flute; Philomel motets and instrumental works of the German DOUBLE & Baroque Orchestra. Handel, Nel dolce dell’oblio & Renaissance composer. TRIPLE CONCER- Tra le fiamme, two important pieces for obbligato TOS OF BACH & TELEMANN recorder & soprano; Telemann, Trio in F; Vivaldi, IN STOCK (Partial listing) Carolina Baroque, Dale Higbee, recorders. All’ombra di sospetto. Dorian. $15 ARS/$17 Others. ____ARCHIPELAGO Alison Melville, recorder & 2-CD set, recorded live. $24 ARS/$28 others. traverso. Sonatas & concerti by Hotteterre, Stanley, ____JOURNEY Wood’N’Flutes, Vicki Boeckman, ____SONGS IN THE GROUND Cléa Galhano, Bach, Boismortier and others. $15 ARS/$17 Others. Gertie Johnsson & Pia Brinch Jensen, recorders. recorder, Vivian Montgomery, harpsichord. Songs ____ARLECCHINO: SONATAS AND BALLETTI Works by Dufay, Machaut, Henry VIII, Mogens based on grounds by Pandolfi, Belanzanni, Vitali, OF J. -

Arts at St. Bede's

Sunday, October 25 San Francisco Renaissance Voices – Viva Italia! oin us for music from Italy’s great castles, cathedrals, Arts at St. Bede’s and countryside, featuring Palestrina’s Missa Nasce Jla gioa mia for six voices, madrigals by Aleotti, Asola, 2015 – 2016 Season Casulana, Croce, Marenzio, Primavera, Striggio, and Vecchi, and commedia dell’arte dance solos featuring SFRV Dance Director Jennifer Meller. St. Bede’s Episcopal Church At door: $30 general/$25 senior/$25 student/$15 under-12 Thomas Pacha Photo: 2650 Sand Hill Road, Menlo Park For more info & advance purchase, see www.sfrvoices.org Sunday, December 13 All performances are at 4:00pm Sunday, November 8 Kitka – Wintersongs Collage Vocal Ensemble – Heavenly Bodies intersongs showcases seasonal music from a wide his Los Altos-base chamber choir, under variety of Eastern European ethnic and spiritual Sunday, September 27 the direction of Amy Hunn, celebrates the Wtraditions. Kitka’s program features rousing Slavic folk St. Bede’s Choir – Fall Evensong Tbeauty and power of bodies both celestial and carols, meditative Eastern and Bosnian-Muslim sacred physical, and features works by Monteverdi, oaring chant, stirring hymnody, works, pagan incantations, Hebrew songs, and lively Mozart, Urmas Sisask, Jonathan Dove, and and dramatic poetry will highlight Romany tunes, all inspired by the customs, beauty, and the Beatles. www.collagevocalensemble.org this Service of Light, which welcomes mystery of wintertime. S $15 suggested donation benefitsInnVision Shelter Network the lengthening shadows of autumn At door: $40 center-front/$35 general/$30 senior/$15 student For more info & advance purchase, see www.kitka.org with a bounteous harvest of music by Sunday, November 22 Hildegard von Bingen, Sister Élise, and Libby Larsen. -

Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European Musical

Ch. 4: Island and Mainland: Toward a Pan-European Style I. Introduction A. European musical style of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries moved from distinct national styles (particularly of the Ars nova and Trecento) toward a more unified, international style. II. English Music and Its Influence A. Fragmentary Remains 1. English music had a style that was distinct from continental music of the Middle Ages. 2. English singers included the third among the consonant intervals. 3. The Thomas gemma Cantuariae/Thomas caesus in Doveria (Ex. 4-3) includes many features associated with English music, such as almost equal ranges in the top two parts and frequent voice exchanges. B. Kings and the Fortunes of War 1. The Old Hall Manuscript contains the earliest English polyphonic church music that can be read today. 2. Copied for a member of the royal family, most of its contents belong to the Mass Ordinary. 3. Henry V, who is associated with the Old Hall Manuscript, holds a prominent place in history of this period. 4. When Henry’s army occupied part of northern France in the early fifteenth century, his brother John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford, was in charge. This brother included the composer John Dunstable (ca. 1390–1453) among those who received part of his estates when he died. 5. Dunstable’s music influenced continental composers. C. Dunstable and the “Contenance Angloise” 1. Dunstable’s arrival in Paris caused the major composers to follow his style, known as la contenance angloise. a. Major-mode tonality b. Triadic harmony c. Smooth handling of dissonance 2. -

Dissertation Final Submission Andy Hillhouse

TOURING AS SOCIAL PRACTICE: TRANSNATIONAL FESTIVALS, PERSONALIZED NETWORKS, AND NEW FOLK MUSIC SENSIBILITIES by Andrew Neil Hillhouse A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrew Neil Hillhouse (2013) ABSTRACT Touring as Social Practice: Transnational Festivals, Personalized Networks, and New Folk Music Sensibilities Andrew Neil Hillhouse Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 The aim of this dissertation is to contribute to an understanding of the changing relationship between collectivist ideals and individualism within dispersed, transnational, and heterogeneous cultural spaces. I focus on musicians working in professional folk music, a field that has strong, historic associations with collectivism. This field consists of folk festivals, music camps, and other venues at which musicians from a range of countries, affiliated with broad labels such as ‘Celtic,’ ‘Nordic,’ ‘bluegrass,’ or ‘fiddle music,’ interact. Various collaborative connections emerge from such encounters, creating socio-musical networks that cross boundaries of genre, region, and nation. These interactions create a social space that has received little attention in ethnomusicology. While there is an emerging body of literature devoted to specific folk festivals in the context of globalization, few studies have examined the relationship between the transnational character of this circuit and the changing sensibilities, music, and social networks of particular musicians who make a living on it. To this end, I examine the career trajectories of three interrelated musicians who have worked in folk music: the late Canadian fiddler Oliver Schroer (1956-2008), the ii Irish flute player Nuala Kennedy, and the Italian organetto player Filippo Gambetta. -

Renaissance Terms

Renaissance Terms Cantus firmus: ("Fixed song") The process of using a pre-existing tune as the structural basis for a new polyphonic composition. Choralis Constantinus: A collection of over 350 polyphonic motets (using Gregorian chant as the cantus firmus) written by the German composer Heinrich Isaac and his pupil Ludwig Senfl. Contenance angloise: ("The English sound") A term for the style or quality of music that writers on the continent associated with the works of John Dunstable (mostly triadic harmony, which sounded quite different than late Medieval music). Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Fauxbourdon: A musical texture prevalent in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance, produced by three voices in mostly parallel motion first-inversion triads. Only two of the three voices were notated (the chant/cantus firmus, and a voice a sixth below); the third voice was "realized" by a singer a 4th below the chant. Glogauer Liederbuch: This German part-book from the 1470s is a collection of 3-part instrumental arrangements of popular French songs (chanson). Homophonic: A polyphonic musical texture in which all the voices move together in note-for-note chordal fashion, and when there is a text it is rendered at the same time in all voices. Imitation: A polyphonic musical texture in which a melodic idea is freely or strictly echoed by successive voices. A section of freer echoing in this manner if often referred to as a "point of imitation"; Strict imitation is called "canon." Musica Reservata: This term applies to High/Late Renaissance composers who "suited the music to the meaning of the words, expressing the power of each affection." Musica Transalpina: ("Music across the Alps") A printed anthology of Italian popular music translated into English and published in England in 1588. -

Medieval Music for Celtic Harp Pdf Free Download

MEDIEVAL MUSIC FOR CELTIC HARP PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Star Edwards | 40 pages | 01 Jan 2010 | Mel Bay Publications | 9780786657339 | English | United States Medieval Music for Celtic Harp PDF Book Close X Learn about Digital Video. Unde et ibi quasi fontem artis jam requirunt. An elegy to Sir Donald MacDonald of Clanranald, attributed to his widow in , contains a very early reference to the bagpipe in a lairdly setting:. In light of the recent advice given by the government regarding COVID, please be aware of the following announcement from Royal Mail advising of changes to their services. The treble end had a tenon which fitted into the top of the com soundbox. Emer Mallon of Connla in action on the Celtic Harp. List of Medieval composers List of Medieval music theorists. Adam de la Halle. Detailed Description. Monophony was replaced from the fourteenth century by the Ars Nova , a movement that developed in France and then Italy, replacing the restrictive styles of Gregorian plainchant with complex polyphony. Allmand, T. Browse our Advice Topics. Location: optional. The urshnaim may refer to the wooden toggle to which a string was fastened once it had emerged from its hole in the soundboard. Password recovery. The early history of the triangular frame harp in Europe is contested. This word may originally have described a different stringed instrument, being etymologically related to the Welsh crwth. Also: Alasdair Ross discusses that all the Scottish harp figures were copied from foreign drawings and not from life, in 'Harps of Their Owne Sorte'? One wonderful resource is the Session Tunes. -

October 2.Qxd

OCTOBER 2009 OCTOBER CLASSICAL new release harharmoniamonia mmundiundi UKUK available 19th October call off 9th October harmonia mundi, AEON, ALIA VOX, ALPHA, AMBRONAY, ARCANA, ARTE VERUM, AUDITE, BEL AIR CLASSIQUES, CALLIOPE, CSO RESOUND, DELPHIAN, FIRST HAND, FUGA LIBERA, GLOSSA, HAT[NOW]ART, K617, KML, LSO LIVE, MARIINSKY, MEDICI ARTS, MIRARE, MODE, NASCOR, OPAL, OPELLA NOVA, ORFEO, PARADIZO, PEARL, PRAGA DIGITALS, RADIO FRANCE, RAM, RCOC, RCO LIVE, RICERCAR, SFZ, SIGNUM CLASSICS, STRADIVARIUS, UNICORN KANCHANA, WALHALL, WERGO, WINTER & WINTER, YSAYE OCTOBER GRAMOPHONE EDITOR’S CHOICE HMU807447/48 Handel Organ Concertos Op. 7 Academy of Ancient Music / Richard Egarr +IRR OUTSTANDING GRAMOPHONE EDITOR’S CHOICE SIGCD155 Liszt Abroad Rebecca Evans (sop), Andrew Kennedy (tenor), Matthew Rose (baritone), Iain Burnside (piano) BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE CHOICE LSO0685 Bartok Bluebeard’s Castle LSO / Valery Gergiev BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE DVD CHOICE Medici Arts 2055488 Mahler Symphony No. 4, Schoenberg Pelleas& Melisande Juliane Banse (soprano); Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra/ Claudio Abbado GRAMOPHONE AWARD FINALIST BAROQUE INSTRUMENTAL HMU907502 PURCELL COMPLETE FANTAZIAS / Fretwork GRAMOPHONE AWARD FINALIST EARLY HMU807489 SONG OF SONGS / Stile Antico “Sumptuously delivered by the peerless Stile Antico.” The Independent HMC992039/40 Barcode: 794881935628 special limited edition with DVD while stocks last HMC902039/40 Barcode: 794881 924523 2 CDs £11.30 until Jan 1st 2010 then £13.47 Josef HAYDN The Creation Julia Kleiter, soprano (Gabriel, Eva); Maximilian Schmitt, tenor (Uriel); Johannes Weisser, bass (Raphael,Adam); RIAS Kammerchor; Freiburger Barockorchester / René Jacobs (conductor) It was on a visit to London in 1791 that Haydn heard several of Handel's oratorios at Westminster Abbey. Astonished by their size and power - "Handel is master of us all," he is said to have declared - he determined to write a similar work himself. -

Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century

David Fallows Songs and Musicians in the Fifteenth Century VARIORUM 1996 CONTENTS Preface vn Acknowledgements V1H ENGLAND English song repertories of the mid-fifteenth century 61-79 Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association 103. London, 1976-77 II Robertus de Anglia and the Oporto song collection 99-128 Source Materials and the Interpretation of Music: A Memorial Volume to Thurston Dart, ed. Ian Bent. London: Stabler & Bell Ltd, 1981 III Review of Julia Boffey: Manuscripts of English Courtly Love Lyrics in the later Middle Ages 132-138 Journal of the Royal Musical Association 112. Oxford, 1987 IV Dunstable, Bedyngham and O rosa be I la 287-305 The Journal of Musicology 12. Berkeley, Calif, 1994 MAINLAND EUROPE The contenance angloise: English influence on continental composers of the fifteenth century 189-208 Renaissance Studies 1. Oxford, 1987 VI French as a courtly language in fifteenth-century Italy: the musical evidence 429-441 Renaissance Studies 3. Oxford, 1989 VI VII A glimpse of the lost years: Spanish polyphonic song, 1450-70 19-36 New Perspectives on Music: Essays in Honor of Eileen Southern, ed. Josephine Wright with Samuel A. Floyd, Jr. Detroit Monographs in Musicology/Studies in Music. Warren, Mich.: Harmonie Park Press, 1992 VIII Polyphonic song in the Florence of Lorenzo's youth, ossia: the provenance of the manuscript Berlin 78.C.28: Naples or Florence? 47-61 La musica a Firenze at tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, ed. Piero Gargiulo. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1993 IX Prenez sur moy: Okeghem's tonal pun 63-75 Plainsong and Medieval Music 1.