Chinese and Russian Information Warfare Approaches Against Nato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's G8 Plans

Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, 2010 Jenilee Guebert Director of Research, G8 Research Group, with Robin Lennox and other members of the G8 Research Group June 7, 2010 Plans for the 2010 G8 Muskoka Summit: June 25-26, Ministerial Meetings 31 2010 1 G7 Finance Ministers 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms 2 G20 Finance Ministers 37 Preface 2 G8 Foreign Ministers 37 Introduction: Canada’s 2010 G8 2 G8 Development Ministers 41 Agenda: The Policy Summit 3 Civil Society 43 Priority Themes 3 Celebrity Diplomacy 43 World Economy 5 Activities 44 Climate Change 6 Nongovernmental Organizations 46 Biodiversity 6 Canada’s G8 Team 48 Energy 7 Participating Leaders 48 Iran 8 G8 Leaders 48 North Korea 9 Canada 48 Nonproliferation 10 France 48 Fragile and Vulnerable States 11 United States 49 Africa 12 United Kingdom 49 Economy 13 Russia 49 Development 13 Germany 49 Peace Support 14 Japan 50 Health 15 Italy 50 Crime 20 Appendices 50 Terrorism 20 Appendix A: Commitments Due in 2010 50 Outreach and Expansion 21 Appendix B: Facts About Deerhurst 56 Accountability Mechanism 22 Preparations 22 Process: The Physical Summit 23 Site: Location Reaction 26 Security 28 Economic Benefits and Costs 29 Benefits 29 Costs 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms AU African Union CCS carbon capture and storage CEIF Clean Energy Investment Framework CSLF Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum DAC Development Assistance Committee (of the Organisation for Economic Co- operation and Development) FATF Financial Action Task Force HAP Heiligendamm L’Aquila Process HIPC heavily -

EU-Korea Convergence and Partnerships 10 Years After the EU-ROK FTA, in the Post Covid Era and Within the US-China Trade War

EU-Korea convergence and partnerships 10 years after the EU-ROK FTA, in the post Covid era and within the US-China trade war Asia Centre is delighted to host a distinguished panel to discuss the current status of EU and Republic of Korea partnerships, relations and cooperation on multilateral issues and focused sectors of mutual interest. Please find some of the papers of the authors-speakers on the following pages. CHAIRS: • Lukas MANDL (chairman of the European Parliament’s Delegation for Relations with the Korean Peninsula) • Jean-François DI MEGLIO (President of Asia Centre) SPEAKERS : Panel 1 : The points of convergence within the analysis of post Covid international relations • Maximilian MAYER (University of Bonn) : introduction • Antoine BONDAZ (FRS, SciencesPo): “The Covid-19 pandemic as a great opportunity for greater EU-Korea coordinAtion And cooperAtion” • Nicola CASARINI (Istituto Affari InternAzionAli): « EU-Korea strAtegic pArtnership ten years after. Opportunities, and challenges, in the age of Covid and mounting US-China tensions » • Paul ANDRE (SciencesPo): « Is KoreA on the threshold of the G7? StrAtegic opportunities and challenges ahead in the perspective of an enlarged G7 » • René CONSOLO (French diplomAt who worked in PyongyAng): « The European Union’s Restrictive Measures against North Korea: a medium term view, beyond the current difficulties. Looking at solutions beyond the deadlock ». Transition: Elisabeth Suh (SWP): « Certain uncertainty – the cyber challeng posed by Pyongyang » Panel 2 : Future opportunities of EU-ROK cooperation in specific areas of competence and excellence • Ramon PACHECO-PARDO (King’s College): « Reassessment of the goals intended and achieved through the EU-ROK FTA » • Tereza NOVOTNA (MArie SklodowskA-Curie Fellow): « WhAt EU-ROK Partnership within the US-China Conflict? » • Brigitte DEKKER (ClingendAel Institute): « EU-ROK digital connectivity: United, we must stand. -

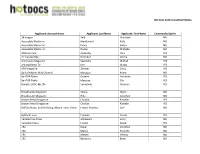

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 Images

Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media Applicant: Account Name Applicant: Last Name Applicant: First Name Community Opt-In 24 images Selb Charlotte NO Accessible Media Inc. MacDonald Kelly NO Accessible Media Inc. Evans Simon NO Accessible Media Inc. Dudas Michelle NO Afisharu.com Zaslavsky Nina YES Air Canada Rep González Leticia NO Alternavox Magazine Saavedra Mikhail YES Arirang Korea TV Kim Mingu YES ATK Magazine Zimmer Cindy YES Balita/Filipino Web Channel Marquez Romy NO BanTOR Radio Qorane Nuruddin YES BanTOR Radio Mazzuca Ola YES Braidio, CKDU 88.1fm Simmonds Veronica YES Broadcaster Magazine Shane Myles NO Broadcaster Magazine Hiltz Jonathan NO Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Broken Pencil Magazine Charkot Richelle YES Buffalo News, Buffalo Rising, Albany Times Union Francis Penders Carl NO ByBlacks.com Franklin Nicole YES Canada Free Press Anklewicz Larry NO Canadian Press Friend David YES CBC Dekel Jonathan NO CBC Mattar Pacinthe NO CBC Mesley Wendy NO CBC Bambury Brent NO Hot Docs 2016 Accredited Media CBC Tremonti Anna Maria NO CBC Galloway Matt NO CBC Pacheco Debbie NO CBC Berry Sujata NO CBC Deacon Gillian NO CBC Rundle Lisa NO CBC Kabango Shadrach NO CBC Berube Chris YES CBC Callender Tyrone YES CBC Siddiqui Tabassum NO CBC Mitton Peter YES CBC Parris Amanda YES CBC Reid Tashauna NO CBC Hosein Lise NO CBC Sumanac-Johnson Deana NO CBC Knegt Peter YES CBC Thompson Laura NO CBC Matlow Rachel NO CBC Coulton Brian NO CBC Hopton Alice NO CBC Cochran Cate YES CBC - Out in the Open Guillemette Daniel NO CBC / TVO Chattopadhyay Piya NO CBC Arts Candido Romeo YES CBC MUSIC FRENETTE BRAD NO CBC MUSIC Cowie Del NO CBC Radio Nazareth Errol NO CBC Radio Wachtel Eleanor NO Channel Zero Inc. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1999, No.36

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Forced/slave labor compensation negotiations — page 2. •A look at student life in the capital of Ukraine — page 4. • Canada’s professionals/businesspersons convene — pages 10-13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE No.KRAINIAN 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine U.S.T continues aidU to Kharkiv region W Pustovoitenko meets in Moscow with $16.5 million medical shipment by Roman Woronowycz the region and improve the life of Kharkiv’s withby RomanRussia’s Woronowycz new increasingprime Ukrainian minister debt for Russian oil Kyiv Press Bureau residents, which until now had produced Kyiv Press Bureau and gas. The disagreements have cen- few tangible results. tered on the method of payment and the KYIV – The United States government “This is the first real investment in terms KYIV – Ukraine’s Prime Minister amount. continued to expand its involvement in the of money,” said Olha Myrtsal, an informa- Valerii Pustovoitenko flew to Moscow on Ukraine has stated that it owes $1 bil- Kharkiv region of Ukraine on August 25 tion officer at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv. August 27 to meet with the latest Russian lion, while Russia claims that the costs when it delivered $16.5 million in medical Sponsored by the Department of State, the prime minister, Vladimir Putin, and to should include money owed by private equipment and medicines to the area’s hos- humanitarian assistance program called discuss current relations and, more Ukrainian enterprises, which raises the pitals and clinics. -

The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Warriors

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WOLF WARRIORS Yun Jiang N 2020, the usually polite and us ‘chequebook diplomacy’ (aid Iconservative diplomats from the and investment to gain diplomatic People’s Republic of China (PRC) recognition vis-à-vis Taiwan) and attracted attention around the world ‘panda diplomacy’ (sending pandas to for breaking form. ‘Wolf warrior build goodwill). diplomacy’ is a term used to describe Wolf Warrior 战狼 was a popular the newly assertive and combative Chinese film released in 2015. It was style of Chinese diplomats, in action followed by a sequel, Wolf Warrior 2, as well as rhetoric. It is not the only which became the highest-grossing diplomacy-related term that China film in Chinese box office history. They became famous for this year; there were both aggressively nationalistic was also ‘mask diplomacy’ (the films, comparable with Hollywood’s shipment of medical goods to build Rambo, portraying the Chinese hero goodwill) and ‘hostage diplomacy’ as someone who saves his compatriots (the detention of foreign citizens in and others from international China to gain leverage over another ‘bad guys’, including American country). Previous years brought mercenaries. The tagline of both films 34 powerful counter-attack only when 35 being attacked’ is more like Kung Fu Panda, while wolf warrior diplomacy is more of a ‘US trait’.1 However it is characterised, the way Chinese diplomats operate reflects the attitude to diplomacy and foreign affairs of the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The discretionary The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Warriors The Rise and Fall of the Wolf Yun Jiang power of even the top foreign policy bureaucrats and diplomats is relatively CRISIS limited in the Chinese system. -

Russia's Europe, 1991–2016

Russia’s Europe, 1991–2016: inferiority to superiority IVER B. NEUMANN* As the Soviet Union fell apart, Russia opted for a foreign policy of coopera- tion with Europe and the West. The following 25 years saw an about-turn from cooperation to conflict. In 2014, having occupied the Crimean peninsula, it aided and abetted an insurgency against the central authorities in neighbouring Ukraine. In 2015, it left the Treaty on Conventional Forces in Europe and began a military buildup along its entire western border. In 2016, it came to the aid of its ally Syria in a way that brought it directly into conflict with western powers. There are a number of ways of accounting for such sea-changes in foreign policy. Some studies set out to explain Russia’s foreign policy by analysing the country’s place in the international system, most often in geopolitical terms.1 Clearly, one reason for Russia’s about-turn is the state’s difficulty in dealing with the downsiz- ing in territory and resources that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the more marginalized place within the state system in which Russia found itself as a result. Other studies aim to demonstrate how Russian foreign policy is deter- mined by structural domestic changes such as bureaucratic in-fighting, the motives of political leaders and so on.2 Such factors are always important in understanding how specific foreign policy decisions come about. A third literature traces the influ- ence of ideas.3 Given that actions depend on how people think about the world, * I thank Amanda Cellini, Minda Holm and Sophie Meislin for assistance and my reviewers for comments. -

Deborah L. Rhode* This Article Explores the Leadership Challenges That Arose in the Wake of the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic and the W

9 RHODE (DO NOT DELETE) 5/26/2021 9:12 AM LEADERSHIP IN TIMES OF SOCIAL UPHEAVAL: LESSONS FOR LAWYERS Deborah L. Rhode* This article explores the leadership challenges that arose in the wake of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and the widespread protests following the killing of an unarmed Black man, George Floyd. Lawyers have been key players in both crises, as politicians, general counsel, and leaders of protest movements, law firms, bar associations, and law enforcement agencies. Their successes and failures hold broader lessons for the profession generally. Even before the tumultuous spring of 2020, two-thirds of the public thought that the nation had a leadership crisis. The performance of leaders in the pandemic and the unrest following Floyd’s death suggests why. The article proceeds in three parts. Part I explores leadership challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic and the missteps that put millions of lives and livelihoods as risk. It begins by noting the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters, and the way that leadership failures in one arena—health, environmental, political, or socioeconomic—can have cascading effects in others. Discussion then summarizes key leadership attributes in preventing, addressing, and drawing policy lessons from major crises. Particular attention centers on the changes in legal workplaces that the lockdown spurred, and which ones should be retained going forward. Analysis also centers on gendered differences in the way that leaders addressed the pandemic and what those differences suggest about effective leadership generally. Part II examines leadership challenges in the wake of Floyd’s death for lawyers in social movements, political positions, private organizations, and bar associations. -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

Timeline of Key Events: March 2011: Anti-Government Protests Broke

Timeline of key events: March 2011: Anti-government protests broke out in Deraa governorate calling for political reforms, end of emergency laws and more freedoms. After government crackdown on protestors, demonstrations were nationwide demanding the ouster of Bashar Al-Assad and his government. July 2011: Dr. Nabil Elaraby, Secretary General of the League of Arab States (LAS), paid his first visit to Syria, after his assumption of duties, and demanded the regime to end violence, and release detainees. August 2011: LAS Ministerial Council requested its Secretary General to present President Assad with a 13-point Arab initiative (attached) to resolve the crisis. It included cessation of violence, release of political detainees, genuine political reforms, pluralistic presidential elections, national political dialogue with all opposition factions, and the formation of a transitional national unity government, which all needed to be implemented within a fixed time frame and a team to monitor the above. - The Free Syrian Army (FSA) was formed of army defectors, led by Col. Riad al-Asaad, and backed by Arab and western powers militarily. September 2011: In light of the 13-Point Arab Initiative, LAS Secretary General's and an Arab Ministerial group visited Damascus to meet President Assad, they were assured that a series of conciliatory measures were to be taken by the Syrian government that focused on national dialogue. October 2011: An Arab Ministerial Committee on Syria was set up, including Algeria, Egypt, Oman, Sudan and LAS Secretary General, mandated to liaise with Syrian government to halt violence and commence dialogue under the auspices of the Arab League with the Syrian opposition on the implementation of political reforms that would meet the aspirations of the people. -

Defending 2020

© 2021 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/defending-2020/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover design by Katya Sankow Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a nonpartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on autocratic efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD has staff in Washington, D.C., and Brussels, bringing together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coer- cion, and cybersecurity, as well as Russia, China, and the Middle East, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frameworks. About the Authors Jessica Brandt is head of policy and research for the Alliance for Securing Democracy and a fellow at the Ger- man Marshall Fund of the United States. She was previously a fellow in the Foreign Policy program at the Brook- ings Institution, where her research focused on multilateral institutions and geopolitics, and where she led a cross-program initiative on Democracy at Risk. Jessica previously served as special adviser to the president of the Brookings Institution, as an International and Global Affairs fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and Inter- national Affairs at Harvard University, and as the director of Foreign Relations for the Geneva Accord. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2020

INSIDE: l Remembering the Crimean Tatars’ Genocide – page 3 l Our community copes with COVID-19 – page 4 l The generation of 1919: three scholars – page 9 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXVIII No. 21 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MAY 24, 2020 $2.00 NEWS ANALYSIS World remembers Genocide Assessing a year of Zelenskyy and foreign policy developments of Crimean Tatar people Presidential Office The Crimean Tatar flag with a black mourning ribbon is displayed in Kyiv. by Roman Tymotsko for raising the Crimean Tatar flag with a Presidential Office of Ukraine mourning ribbon and urged the public to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy speaks during his press conference on May 20. KYIV – On May 18, Ukraine remembered light candles in their windows on the night the victims of Joseph Stalin’s genocidal of May 17-18. by Bohdan Nahaylo Ukraine made no mistake in making the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people President Volodymyr Zelenskyy European choice. After all, a friend in need from Crimea. On that day in 1944, the first addressed the nation on May 18. “We believe KYIV – While attention in Ukraine has is a friend indeed,” President Zelenskyy trainloads of Crimean Tatars were forcibly that the day will surely come when Crimea remained focused on coping with the coro- emphasized. He elaborated that the EU resettled from the peninsula to Central Asia will return to Ukraine,” he said. “Crimean navirus pandemic and meeting the condi- funds will also help guarantee Ukraine’s and Siberia. In total, about 200,000 people Tatars and Ukrainians will return to their tions to secure further financial support macroeconomic stability. -

Report to the Nation 2019

REPORT TO THE NATION: 2019 FACTBOOK ON HATE & EXTREMISM IN THE U.S. & INTERNATIONALLY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………............................3 Executive Summary: Report to the Nation, 2019…………………………………………………………………......................5–95 I. LATEST 2018 MAJOR U.S. CITY DATA………………………………………………………………………......................5 II. BIAS BY CITY IN 2018…………………………………………………………………......................................................6 III: 2019/2018 Latest Major U.S. City Trends: By City & Bias Motive………………………………………..................7 IV: OFFICIAL FBI & BJS DATA………………………………… ……………………………………………..........................12 V: EXTREMIST AND MASS HOMICIDES……………………………………………...................................................18 VI: HATE MIGRATES AND INCREASES ONLINE……………………………………………………………....................22 VII: RUSSIAN SOCIAL MEDIA MANIPULATION CONTINUES…………………………………………….................29 VIII: FLUCTUATIONS AROUND CATALYTIC EVENTS AND POLITICS……………………………………..............32 IX: U.S. NGO DATA OVERVIEW – EXTREMIST GROUPS………………………………………….………..................38 X: U.S. NGO DATA – RELIGION & ETHNIC HATE …………………………………….............................................39 XI: U.S. NGO DATA – EMERGING HATREDS: HOMELESS, TRANSGENDER & JOURNALISTS ……….........44 XII: POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND THREATS………………………………………………………………….....................48 XIII: HATE CRIME VICTIMS AND OFFENDERS…………………………………………………..…………....................54 XIV: HATE CRIME PROSECUTIONS……………………………………………………………………………....................61 XV: HATE