Opium Poppy (Papaver Somniferum) S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rochester. N. T.-For the Week Ending Saturday, September 14,1861

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Newspapers Collection 1 TWO DOLLARS A. YEAR.] "PROGRESS AND IMPROVEMENT. [STNGKL.E NO. B^OTJR CENTS. VOL XH. NO. 37.} ROCHESTER. N. T.-FOR THE WEEK ENDING SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 14,1861. {WHOLE NO. 609. in June for the first time in the second year. The mitted to grow. All weeds that have commenced RETURN-TABLE APPLE PAEEE. MOORE'S RURAL NEW-YORKER, best plan is to turn on your stock when the seed flowering should be collected together in a pile, dried AN ORIGINAL WEEKLY. ripens in June. Graze off the grass, then allow the and burned. If gathered before flowers are formed AMONG all the inventions AGBICUITURAL, LUEKARY ANB FAMILY JOURNAL. fall growth, and graze all winter, taking care never to they may be placed upon the compost heap and for paring apples which have feed the grass closely at any time.1' mixed with fermenting manures. CONDUCTED BY D. D. T. MOORE, come under our observation The number of seeds produced by our common With an Abie Corps of Assistants and Contributors, Canada Thistles. of late years, the "Return- weeds is really astonishing to those who have no Table Apple Parer," recent- CHAS. D. BKASDON1, Western Corresponding Editor. SOME years since, in our investigations among studied the matter. A good plant of dock will ripen ly patented lay WHITTEMORE the flowers and weeds, we found what was new to us from twelve to fifteen thousand seeds, burdock over BROTHERS, Worcester, Mass., — a Canada thistle with white flowers. In the twenty thousand, and pig-weed some ten thousand. -

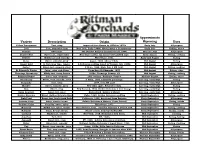

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

SCS News Fall-Winter 2006, Volume 3, Number 5

Swedish Colonial News Volume 3, Number 5 Fall/Winter 2006 Preserving the legacy of the Royal New Sweden Colony in America House of Sweden Opens New Embassy of Sweden is a Washington Landmark Ola Salo, lead singer of the Swedish rock band “The Ark,” performs during the opening of the House of Sweden. A large crowd was on hand to inaugurate of Sweden and many other dignitaries were In this issue... Sweden’s new home in America, the House on hand for the opening ceremonies. With of Sweden. “House of Sweden is much more a K Street location on Washington Harbor, FOREFATHERS 2 than an embassy. It is a place for Sweden and Sweden has one of the best addresses in DIPLOMACY 5 Europe to meet America to exchange ideas Washington, DC. House of Sweden emanates and promote dialogue. This gives us a great a warm Nordic glow from its backlit glass MARITIMES 6 opportunity to carry on public diplomacy and facade with patterns of pressed wood. It is a project our modern and dynamic Sweden,” YORKTOWN 12 beacon of openness, transparency and hope said Gunnar Lund, Sweden’s Ambassador to the future. EMBASSY 16 to the United States. The King and Queen (More on page16) FOREFATHERS Dr. Peter S. Craig Catharina, Nils, Olle, Margaretta, Brigitta, Anders and Nils Andersson and Ambora. (See “Anders Svensson Bonde and His Boon Family,” Swedish Colonial News, Vol. 1, No. 14, Fall 1996). His Lykins Descendants 2. Christina Nilsdotter, born in Nya Kopparberget c. The freeman Nils Andersson, his wife and at 1639, married Otto Ernest Cock [originally spelled Koch], least four children were aboard the Eagle when that a Holsteiner, c. -

Green, Ella Jane (Williams)

BIG GREEN by Ella Jane (Williams) Green 1936 Transcribed by Douglas Williams 1936 Original publication held at Harrington City Library, Harrington, WA Introduction The following pages were transcribed from photocopies of a book written by Ella Jane Green in 1936. The photocopies were obtained from Marge Womach, of Harrington, Washington, through the Harrington City Library. Marge also provided copies of a partial transcription of the book, which included the preface. Originally this book, entitled “Big Geen”, was 75 type written pages, with editorial remarks written in pencil. These editorial remarks were taken into consideration during the transcription. All editorial changes are included in this transcription, with major editorial changes to the manuscript being referenced by footnotes. Other minor editorial changes like spelling, grammar and sentence constructions are not noted. Most misspellings and grammatical errors contained in the original manuscript are preserved in this transcription. Ella Jane Green is my 1st cousin 3 times removed, through her first cousin Melville Williams, the son of her uncle Jeremiah, or Uncle Doc as Ella calls him. Ella begins her life story by mentioning her grandfather, Isaac Burson Williams. Isaac was born in Bucks County, PA around 1794. He comes from a long line of Williams who have been in this land for hundreds of years. Ella’s great great great grandfather, Jeremiah, was born in Boston in 1683 to Joseph and Lydia Williams. At the end of this book are provided a couple of resources. First, you will find the obituaries of John and Ella Green. In addition, I have provided a partial descendant report for Joseph and Lydia Williams of Boston. -

SCS News, Winter 2011, Volume 4, Number 3

Swedish Colonial News Volume 4, Number 3 Winter 2011 Preserving the legacy of the New Sweden Colony in America Madame Anna Stedham, A Swedish-American Swede and her family By Margaretha Hedblom, Translated by Kim-Eric Williams Editor’s Note: The Timen Stiddem Society was organized in 1998 by three descendents of the original New Sweden The old remaining ChUrch books of MalUng Parish in doctor on the Delaware, Timen Stiddem (1638, SWeden’s Dalarna proVince contain a Wealth of information 1640-44, 1654). When Richard Steadham became editor of the Timen Stiddem Society Newsletter a little aboUt the liVes of eVerYdaY people Who liVed in this rUral over a year ago, he inherited a project from the pre - area. While it Was the aUthor’s intent to stUdY the caUses of vious editor, David R. Stidham, an article about infant mortalitY at the end of the Eighteenth CentUrY, an Timen’s daughter Anna and her life UnUsUal death notice in those records caUght her eYe and and family back in Sweden. Written by changed the coUrse of her research. The record stated Swedish researcher Margaretha At Hole. Madame Ann a S tedham, Hedblom, it was first published in the simplY: book Skinnarebygd (the 2009 yearbook born in America 1704. of the Malung Historical Society). She Married 1721 to Sheriff then offered the article for publication And(ers) Engman, in the Stiddem Newsletter . The first hurdle to be overcome was continued on page 2 the article’s translation from Swedish to English. A rough word-for-word translation clear - ly indicated the article was intended for a Swedish audience and would need editing before publication in America. -

Apple Variety Harvest Dates Weber's Apple Variety Harvest Dates

Weber's Apple Variety Harvest Dates Weber's Apple Variety Harvest Dates VARIETY RIPENS FLAVOR USES DESCRIPTION VARIETY RIPENS FLAVOR USES DESCRIPTION Crisp, rich taste and soft texture, great for Cross of Red Delicious and McIntosh, good Lodi Early July Tart B C Empire Late Sept Sweet B E applesauce all-purpose apple Sweet & Sweet eating apple, Excellent for eating, Cross of sweet Golden Delicious and tart Pristine Mid July E Jonagold Late Sept Slightly Tart B C E Tart cooking and sauce Jonathan Sweet & Crisp, rich taste and soft texture, great for Zestar Mid August B C E Ambrosia Early October Sweet E Crisp and Sweet, Best Flavor Tart applesauce Summer Good for pies & applesauce, best cooking Sweet & Excellent dessert apple, also know as Mid August Tart B C Crispin October C E Rambo apple of the summer Juicy Mutsu Chance seedling discovered in a Gala Late August Sweet E Rich, full flavor, best for eating Cameo Mid October Sweet Tart B C E Washington orchard in 1980's Sweet & Firm, crisp, does not bruise easily, slow Blondee Early Sept E Ida Red Mid October Slightly Tart B C E Excellent pie apple Tart browning, long storage life Cross of Macoun and Honeygold, crunchy Cross of Golden Delicious and York Honey Crisp Early Sept Sweet E Nittany Mid October Mildly Tart B C E and delicious Imperial Day Break Sweet & Crisp & juicy, delicious snack and salad Stayman Mid Sept E Mid October Fairly Tart B C E Crisp & juicy, great all-purpose apple Fuji Firm apple Winesap Arkansas Firm, crisp, multipurpose apple, dark peel, Cortland Mid Sept Mildly Tart B E Good for salads, does not darken when cut Late October Tart B C E Black pale yellow flesh. -

Glenmont Estate, Thomas Edison National Historical Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2011 Glenmont Estate Thomas Edison National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Glenmont Estate Thomas Edison National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. -

December 2003, Volume 21 No. 4

On The Fringe Journal of the Native Plant Society of Northeastern Ohio 2003 Annual Dinner Our 21st Annual Dinner guests enjoyed beautiful weather, elegant surroundings in the Dinosaur Hall of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and a marvelous talk by Ann Haymond Zwinger sponsored jointly by the Museum’s Explorer Series. The 500-seat auditorium was filled almost to capacity. Zwinger’s subject was American alpine tundra plants, and she concentrated on those growing in the southern Rockies of Colorado where the descent from Asian roots has been unbroken by glaciation or other disruptions. The recipients of the Native Plant Society’s Annual Grant of $500 were officially recognized at the dinner. Ann Malmquist prefaced her announcement of the award with an appreciation of the CMNH and its growing importance as an intellectual and educational resource in Ohio and nearby states. RENEW NOW Our membership year runs from January to December. Please renew at the highest possible level for 2004 2003 Annual Grant Cleveland Museum of Natural History Tonight we award the Annual Grant to two students at The Dayton Museum of Natural History is no longer collection- Cleveland State University, Timothy Jones and Pedro Lake. based and has fired all of its curators. The Cincinnati Museum of They are Seniors at CSU and former students of George Natural History has moth-balled all of its collections and has laid Wilder. Pedro is also involved in creating a Manual of the off the curatorial staff. Columbus has NO natural history museum. Between New York and Chicago, only the Cleveland Museum of Grasses of Ohio with completion due in Spring Natural History and the Carnegie Museum still operate at full tilt. -

How to Discover Traditional Varieties and Shape in a National Germplasm Collection: the Case of Finnish Seed Born Apples (Malus × Domestica Borkh.)

sustainability Article How to Discover Traditional Varieties and Shape in a National Germplasm Collection: The Case of Finnish Seed Born Apples (Malus × domestica Borkh.) Maarit Heinonen * and Lidija Bitz Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Production Systems, Plant Genetics, Myllytie 1, 31 600 Jokioinen, Finland; lidija.bitz@luke.fi * Correspondence: maarit.heinonen@luke.fi; Tel.: +358-29-5326117 Received: 1 November 2019; Accepted: 4 December 2019; Published: 7 December 2019 Abstract: Cultivated apple (Malus domestica Borkh.) is a major crop of economic importance, × both globally and regionally. It is currently, and was also in the past, the main commercial fruit in the northern European countries. In Finland, apple trees are grown on the frontier of their northern growing limits. Because of these limits, growing an apple tree from a seed was discovered in practice to be the most appropriate method to get trees that bear fruit for people in the north. This created a unique culturally and genetically rich native germplasm to meet the various needs of apple growers and consumers from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s. The preservation, study and use of this genetic heritage falls within the mandate of the Finnish National Genetic Resources Program. The first national apple clonal collection for germplasm preservation was reorganized from the collections of apple breeders. The need to evaluate the accessions, both in this collection and possible missing ones, to meet the program strategy lead us to evaluate the Finnish apple heritage that is still available in situ in gardens. In this article we use multiple-approach methodologies and datasets to gain well-described, proof-rich samples for the trueness-to-type analysis of old heirloom apple varieties. -

Christina Ollesdotter and Her Walraven

Swedish News ColoniaVolume 3, Number 4 l Spring/Summer 2006 Preserving the legacy of the Royal New Sweden Colony in America Franklin and the Swedes Swedes Inextricably Linked To Franklin and America Death of Benjamin Franklin with Swedish Pastor Nicholas Collin present (tall figure in the center). The Tercentennial celebration of the Morton, Adof Ulrich Wertmüller, Nicholas In this issue... life of Benjamin Franklin during 2006 Collin, and the numerous Colonial Swedes FOREFATHERS 2 is of prominent worldwide historical who joined Washington’s Army, are but significance. His contributions to the a few examples of these people whose ECONOMY 5 arts and sciences literally changed the contributions helped to forge this new course of history. What may be lesser DESCENDANTS 6 known, however, is the significant role nation. Internationally, Sweden was the MILESTONES 12 that the Colonial Swedes played not only first neutral European nation to negotiate in impacting Franklin’s life, but in the a treaty of trade and amity with the United CELEBRATIONS 16 forming the United States of America. John States. (More on pages 10 & 11) FOREFATHERS Dr. Peter S. Craig Point” (later called Middle Borough, now Richardson Christina Ollesdotter Park in Wilmington) was granted on 25 March 1676. and Her Walraven Descendents The will of Walraven Jansen DeVos was proved on Among the passengers arriving at Fort Christina on the 1 March 1680/1. The will left one-half of his lands to Kalmar Nyckel and Charitas in November 1641 were three the eldest son living at home – Gisbert Walraven – with small orphans, Jöns (Jonas) Ollesson, Helena Ollesdotter the other half going to his youngest son Jonas Walraven and Christina Ollesdotter. -

Water-Cure Journal V16 N1 Jul 1853

HEFORMS, DEVOTED TO |pi0l0gSt igtopt|gt anlr t|e f atos of fife* . XVI. NO. 1.] NEW YORK, JULY, 1$53. * [$1.00 A YEAR. PUBLISHED B V are not so numerous as npou the palm of the hand, W&Ux~€n:t <£**aq*. but Dr. Wilson estimates, after giving much attention to the subject, that 2SO0 may be taken as a fair ave Fotoieirs ^K|5 MleUs, rage of the number of pores in a square inch over the Here each Contributor presents freely his or her own Opinion*, and is surface generally, and 700, consequently, is the num No. 131 Nassau Street. New York. » alone responsible for them. We do not necessarily endorse all that w« print, batdastin our readers to " P*ovx All Tiiixaa " and to "Hold ber of inches in length. The number of square inches Fast " only ** the Good." in a man of ordinary size is 2500 ; the number of Contents. pores, therefore, mast be 7,000,000 ; the number of Watmh-Ccbk Eutts, . Tin Mom re, .... Iuaensiblo Perspiration, July Sentiments, inches of perspiratory tube 1,750,000, a sum equal to Dyl»« M.scili.any, . about twenty-eight miles! Considering, then, tho Ft HiSLGfiV, A Disappointed Subscriber, vastness of the perspiratory system, are we not most Notes ou Fruils, . Hygiune of Nursing, . 16 forcibly reminded of the necessity of attention to the Fac a JJTB 1 >!':-.■ S), Ho:ne Practice in California, 16 condition of the skin ? Do we not see, also, how ad Hints to n, A Rap on the Knock Kb, 17 Diary of a Physician, . -

Retail Price List for 2020

RETAIL PRICE LIST FOR 2020 Printed by Botanical Name Botanical SKU Size Retail Botanical SKU Size Retail Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Abies koreana 'Cis' Cis Korean Fir-dwf A020GC #3 32.00 A059GG #7 147.00 Abelia x grandiflora 'Ed Goucher' Ed Goucher Abelia-pink Abies koreana 'Horstmann's Silberlocke' Horstmann's Silberlocke Korean Fir A010GC #3 32.00 A055HG 3/4'b&b 251.00 Abelia x grandiflora 'Kaleidoscope' Kaleidoscope Abelia-variegated A055GE #5 184.00 A012GC #3 37.25 Abies nordmanniana Nordmann Fir Abelia x grandiflora 'Radiance' PP21929 Radiance Glossy Abelia-var.-white A068HI 5/6'b&b 200.00 A030GC #3 40.00 A068HK 6/7'b&b 275.00 Abelia x grandiflora 'Rose Creek' Rose Creek Abelia-compact A068HP 7/8'b&b 353.00 A015GC #3 32.00 A068HQ 8/10'b&b 466.00 Abies alba 'Green Spiral' Weeping Silver Fir Abies procera 'Glauca Prostrata' Noble Fir-blue Prostrate A033GG #7 260.00 A070GC #3 140.00 A070GG #7 259.00 Abies amabilis 'Spreading Star' Pacific Silver Fir-dwf. Acanthopanax sieb. 'Variegata' Fiveleaf Aralia-var. A057GG #7 288.00 A067GB #2 40.00 Abies balsamea 'Piccolo' Piccolo Balsam Fir-dwf Acanthus mollis Bear's Breeches-white/purple Bracts A036GC #3 82.00 A700GA #1 13.00 Abies balsamea var. phanerolepis Canaan Fir Acer campestre 'Carnival' Carnival Hedge Maple-var. A034HK 6/7'b&b 307.00 A034HP 7/8'b&b 388.00 A079GG #7 178.00 A034HQ 8/10'b&b 502.00 Acer griseum Paperbark Maple Abies concolor White Fir A080KC 2.5/3"cal 680.00 A040HS 10/12'b&b 931.00 A080KB 2/2.5"cal 489.00 A040HI 5/6'b&b 275.00 A080GP #20 366.00 A040HK 6/7'b&b 332.00