Urry-Globalising-The-Tourist-Gaze.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfihn master. UMI fihns the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 A PEOPLE^S AIR FORCE: AIR POWER AND AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE, 1945 -1965 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Steven Charles Call, M.A, M S. -

Touching the Face of God: Religion, Technology, and the United States Air Force

Touching the Face of God: Religion, Technology, and the United States Air Force Timothy J. Cathcart Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Science and Technology Studies Dr. Shannon A. Brown, Chair Dr. Lee L. Zwanziger Dr. Janet E. Abbate Dr. Barbara J. Reeves 3 December 2008 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: united states air force, religion, military technology, military culture, social construction of technology Copyright © 2008, Timothy J. Cathcart Touching the Face of God: Religion, Technology, and the United States Air Force Timothy J. Cathcart ABSTRACT The goal of my project is a detailed analysis of the technological culture of the United States Air Force from a Science and Technology Studies (STS) perspective. In particular, using the metaphor of the Air Force as religion helps in understanding a culture built on matters of life-and-death. This religious narrative—with the organizational roles of actors such as priests, prophets, and laity, and the institutional connotations of theological terms such as sacredness—is a unique approach to the Air Force. An analysis of how the Air Force interacts with technology—the very thing that gives it meaning—from the social construction of technology approach will provide a broader understanding of this relationship. Mitcham’s dichotomy of the engineering philosophy of technology (EPT) and the humanities philosophy of technology (HPT) perspectives provides a methodology for analyzing Air Force decisions and priorities. I examine the overarching discourse and metaphor—consisting of techniques, technologies, experiences, language, and religion—in a range of historical case studies describing the sociological and philosophical issues of the Air Force. -

James Sweet Offline Editor CV Credits 2016 W/Bio.Pages

James Sweet - Editor Credit Listing I am a creative Avid, Premiere and Final Cut Editor with extensive experience editing for productions ranging from 'Springwatch' to 'Flog It' and corporate promotional films. I am passionate about music, sound, film and technology which has given me an intuitive feel for rhythm and provided me with visual flair. I have a dedicated work ethic maintaining a high attention to detail. I view editing as part of a exciting collaboration which provides opportunities to develop and significantly contribute in the making of something new and creative. ‘James has done a great job, he’s hard working, talented, creative and has a real ear for music and is a joy to work with – highly recommend him’. Lorna Copeland - BBC Production Manager Contact - 07917315814 [email protected] Sarah Cox and Frankie Dotorri Car Pool Eps 1 and 2 Kathy Stringer - Equine Productions Offline and Online Editor Flog It, BBC 1 Eps 50 and 52, Croome, 44min x 2 Director - Clare Wilmshurst Series producer – Louise Hibbins Bargain Hunt, BBC 1 Eps 25 and 27, Series 45, 44min x 2 Director - Kate Thomas-Couth Flog It, Reversions, BBC 1 Flog It Reversions Series 13 and 14 15 x 1 Hour Episodes, BBC 1 Lynette Quinlan, Director BBC Earth Project Holland America 20 x 5min Promotional Clips Jo Boyle Flog It, BBC 1 Eps 23 and 24, Greenwich, Series 15, 44min x 2 Director - Michelle Pascal Series producer – Louise Hibbins. Attenborough and the Giant Dinosaur Web Clips Editor, BBC Earth, 2015 Director - Charlotte Scott Life In The Air, (Last Minute Changes) -

Geography Super Curriculum Year 7

Geography Super Curriculum Year 7 Map Skills Extreme China Ecosystems Rivers Environments School library section 551, School library section 551 School library section 951 School library section School library section 912 Extreme Earth, Visual Travel Through China, 574.5/581 Planet Habitats, 551.48 Mapping Britain’s Mapping Britain’s Explorers 551.2 Come on a journey of Louise & Richard Spilsbury Landscapes, Rivers, by Landscapes, Coasts, by Geography Fact Files, discovery by Lynn Huggins- (581) Horrible Geography: Barbara Taylor (551.48) Barbara Taylor (551.4) Deserts by Anna Cooper (951) Chinese Bloomin’ Rainforest Geography Fact Files, Mapping Britain’s Claybourne (551.41) Focus, Changing China, by Rivers by Mandy Ross Landscapes, Rivers, by Horrible Geography - Marta Block (551.48) Horrible Barbara Taylor (551.48) Bloomin' Rainforests Geography - Raging Rivers Children’s Atlas (912) Harry (2001) (2000) Potter, (Marauder's Map) JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (map of Middle Earth) Master and commander Plant Earth – Deserts, Supersized Earth – Episode Ecosystems class clips, BBC BBC Human PlanetFriend (2003) Mountains, From Pole to 2 Bridge Building Mulan http://www.bbc.co.uk/ or foe? Lord of the rings (2001) Pole. (1998) education/ topics/ Supersized Earth, episode BBC Human Planet: Arctic ztgw2hv/ resources/1 3, Food, Fire and Water – Life in the deep freeze. BBC Human Planet – Jungles. (Water) Deserts – Life in the Planet Earth, Jungles Avatar Into the wild (2007) Planet furnace (2009) Madagascar (2005) Earth, Fresh Water Mountains – life in the air The history of maps. When, How to plants adapt to Choose one animal that is Research and create fact files Research about the past, why and how did the OS map living in threatened by China’s for 5 of the world’s main present and future plans begin? When and why did deserts/rainforests/pol ar development. -

Made Outside London Programme Titles Register 2016

Made Outside London programme titles register 2016 Publication Date: 20 September 2017 About this document Section 286 of the Communications Act 2003 requires that Channels 3 and 5 each produce a suitable proportion, range and value of programmes outside of the M25. Channel 4 faces a similar obligation under Section 288. On 3 April 2017, Ofcom became the first external regulator of the BBC. Under the Charter and Agreement, Ofcom must set an operating licence for the BBC’s UK public services containing regulatory conditions. We are currently consulting on the proposed quotas as set out in the draft operating licence published on 29 March 2017. See https://www.ofcom.org.uk/consultations-and- statements/ofcom-and-the-bbc for further details. As our new BBC responsibilities did not start until April 2017 and this report is based on 2016 data, the BBC quotas reported on herein were set by the BBC Trust. This document sets out the titles of programmes that the BBC, ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5 certified were ‘Made outside of London’ (MOL) productions broadcast during 2016. The name of the production company responsible for the programme is also included where relevant. Wherever this column is empty the programme was produced in-house by the broadcaster. Further information from Ofcom on how it monitors regional production can be found at https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/87040/Regional-production-and-regional- programme-definitions.pdf. The three criteria under which a programme can qualify as MOL are: i) The production company must have a substantive business and production base in the UK outside the M25. -

Fourth World Without Needing to Modify It As Heavily

Contents Introduction 2 Nethermancer 25 Obsessions 52 Goals 2 Nethermancy Spells 27 Questor 52 Provenance 2 Scout 29 Astral Tourist 52 What is the same? 2 Sky Raider 31 Captain 52 What is different? 2 Swordmaster 33 Horror Stalker 53 Poisoner 53 On Adepts & Threads 3 Thief 35 Trollmoot Outcast 53 Using threads 3 Troubadour 37 Advancement strategies 3 Front: Emergence 54 Warrior 39 Species 3 Front: Mists 55 Hirelings 4 Weaponsmith 41 Hacking Dungeon World for play in the world of Earthdawn® Selecting a Discipline 4 Wizard 43 by Lester Ward Moves 5 Wizard Spells 45 version 1.1 On basic moves 5 On Relics 47 On special moves 5 Ranks 47 License On threads 5 Additional tags 47 Earthdawn® is a Registered Trademark of FASA Corporation. Used without permission. All Rights Reserved. On Passions 6 Keys, deeds and demands 47 • First Edition is the original game created and published by FASA Corporation in 1993. On spellcasting 6 Mundane items 47 • Second Edition was published by Living Room Games (licensed from FASA Corporation) in 2001. On blood magic 7 Trifles 47 • Classic Edition was published by RedBrick Limited (licensed from FASA Corporation) in 2005. On bonded groups 8 Trinkets 48 • Third Edition was published by RedBrick LLC and Mongoose Publishing (licensed from FASA Corporation) Wonders 48 in 2009. Air Sailor 9 Relics 49 • Revised Edition was published by FASA Games, Inc. (licensed from FASA Corporation) in 2012. Archer 11 • Fourth Edition will be published by FASA Games, Inc. (licensed from FASA Corporation) in 2015. Beastmaster 13 On Animals & Airships 50 Any use of copyrighted material or trademarks of FASA Corporation, Living Room Games, RedBrick Limited, Cavalryman 15 On Monsters 51 RedBrick LLC, Mongoose Publishing or FASA Games, Inc. -

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING the BATTLE of the SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: a PYRRHIC VICTORY by Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., Univ

THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY By Thomas G. Bradbeer M.A., University of Saint Mary, 1999 Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Committee members ____________________ Jonathan H. Earle, PhD ____________________ Adrian R. Lewis, PhD ____________________ Brent J. Steele, PhD ____________________ Jacob Kipp, PhD Date defended: March 28, 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Thomas G. Bradbeer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ___________________ Chairperson Theodore A. Wilson, PhD Date approved March 28, 2011 ii THE BRITISH AIR CAMPAIGN DURING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME, APRIL-NOVEMBER, 1916: A PYRRHIC VICTORY ABSTRACT The Battle of the Somme was Britain’s first major offensive of the First World War. Just about every facet of the campaign has been analyzed and reexamined. However, one area of the battle that has been little explored is the second battle which took place simultaneously to the one on the ground. This second battle occurred in the skies above the Somme, where for the first time in the history of warfare a deliberate air campaign was planned and executed to support ground operations. The British Royal Flying Corps (RFC) was tasked with achieving air superiority over the Somme sector before the British Fourth Army attacked to start the ground offensive. -

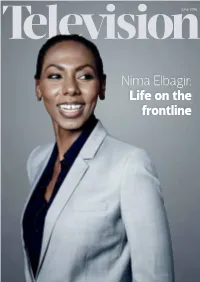

Nima Elbagir: Life on the Frontline Size Matters a Provocative Look at Short-Form Content

June 2016 Nima Elbagir: Life on the frontline Size matters A provocative look at short-form content Pat Younge CEO, Sugar Films (Chair) Randel Bryan Director of Content and Strategy UK, Endemol Shine Beyond UK Adam Gee Commissioning Editor, Multi-platform and Online Video (Factual), Channel 4 Max Gogarty Daily Content Editor, BBC Three Kelly Sweeney Director of Production/Studios, Maker Studios International Andy Taylor CEO, Little Dot Studios Steve Wheen CEO, The Distillery 4 July The Hospital Club, 24 Endell Street, London WC2H 9HQ Booking: www.rts.org.uk Journal of The Royal Television Society June 2016 l Volume 53/6 From the CEO The third annual RTS/ surroundings of the Oran Mor audito- Mockridge, CEO of Virgin Media; Cathy IET Joint Public Lec- rium in Glasgow. Congratulations to Newman, Presenter of Channel 4 News; ture, held in the all the winners. and Sharon White, CEO of Ofcom. unmatched surround- Back in London, RTS Futures held Steve Burke, CEO of NBCUniversal, ings of London’s Brit- an intimate workshop in the board- will deliver the opening keynote. ish Museum, was a room here at Dorset Rise: 14 industry An early-bird rate is available for night to remember. I newbies were treated to tips on how those of you who book a place before was thrilled to see such a big turnout. to secure work in the TV sector. June 30 – just go to the RTS website: Nobel laureate Sir Paul Nurse gave a Bookings are now open for the RTS’s rts.org.uk/event/rts-london-conference-2016. -

Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the Life of a General N/A 5B

20050429 031 PAGE Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, igathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports 1(0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. t. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 2000 na/ 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Hoyt S. Vandenberg, the life of a general n/a 5b. GRANT NUMBER n/a 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Meilinger, Phillip S n/a 5e. TASK NUMBER n/a 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER n/a 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER Air Force History Support Office 3 Brookley Avenue Box 94 n/a Boiling AFB DC 20032-5000 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR'S ACRONYM(S) n/a n/a 11. -

Air and Space Power Journal, Published Quarterly, Is the Professional Flagship Publication of the United States Air Force

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen John P. Jumper Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Donald G. Cook http://www.af.mil Commander, Air University Lt Gen Donald A. Lamontagne Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education Col Bobby J. Wilkes Editor Col Anthony C. Cain http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Senior Editor Lt Col Malcolm D. Grimes Associate Editors Lt Col Michael J. Masterson Maj Donald R. Ferguson Professional Staff Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Larry Carter, Contributing Editor http://www.au.af.mil Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager Air and Space Power Chronicles Luetwinder T. Eaves, Managing Editor The Air and Space Power Journal, published quarterly, http://www.cadre.maxwell.af.mil is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the presentation and stimulation of innova tive thinking on military doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of na tional defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanc tion of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. Articles in this edition may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If they are reproduced, Visit Air and Space Power Journal on-line the Air and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. -

September/October 2017

Summer Optics Sale AUDUBON SOCIETY of PORTLAND — Page 9 SEPTEMBER/ Black-throated OCTOBER 2017 Gray Warbler Volume 81 Numbers 9&10 Warbler Special Issue: Our Five-Year Plan Working to protect the Greater Sage-Grouse. Bald Eagle receives expert care at the Wildlife Care Center. Exploring the land at Marmot. Photo by Scott Carpenter Photo by Ali Berman Photo by Ali Berman Our Exciting Future! Introducing Portland Audubon’s Strategic Plan Dear Portland Audubon Members, prevail against this current. Lastly, the demographics of our region are increasingly diverse, and Portland Audubon and Welcome to an exceptional issue of the Warbler. its supporters must be as well if we’re to remain an effective Throughout our organization’s 115-year history, the voice for birds and nature. strategic use of our people and resources to protect native birds, other wildlife, and their habitat has kept Portland Thanks to our broad array of programs—from educating Audubon at the forefront of Oregon’s conservation kids about the natural world, to training supporters how movement. Whether sparking creation of the West’s first to influence policy decisions—Portland Audubon occupies national wildlife refuges, pioneering the concept of “wild in a unique place that allows us to make the most of today’s the city” to protect urban habitat, or helping pass statewide challenges and opportunities. That’s because we not only legislation to fund Outdoor School for every child, clear nurture and expand people’s love of nature, we also enlist our strategy has guided our success in supporters in efforts to make a difference. -

For Black Airmen, Disparities Persist in USAF Life, Culture, and Promotions | 28

Faster Pilot The Goldfein Years 37 | Long-range Strike 46 | Spaceplanes, Then and Now 55 Training 16 BLACK AND AIR FORCE BLUE For Black Airmen, disparities persist In USAF life, culture, and promotions | 28 July/August 2020 $8 Published by the Air Force Association STAFF Publisher July/August 2020. Vol. 103, No. 7 & 8 Bruce A. Wright Editor in Chief Tobias Naegele Managing Editor Juliette Kelsey Chagnon Editorial Director John A. Tirpak News Editor Amy McCullough Assistant Managing Editor Chequita Wood Senior Designer Dashton Parham Pentagon Editor Brian W. Everstine Tech. Sgt. Jake Barreiro Sgt. Jake Tech. Digital Platforms DEPARTMENTS FEATURES Senior Airman Editor 2 Editorial: Power 8 Q&A: The Future of the Expeditionary Force Cody Mehren Jennifer-Leigh Plays and signals to a B-2 Oprihory Competition Lt. Gen. Mark D. Kelly, incoming head of Air Combat Spirit bomber during a refuel- Senior Editor By Tobias Naegele Command, speaks with John A. Tirpak about the Rachel S. Cohen changes coming to USAF. ing stop at An- 3 Letters dersen Air Force Production Base, Guam. Manager 4 Index to 28 Leveling the Field Eric Chang Lee Advertisers By Rachel S. Cohen Photo Editor 7 Verbatim The Air Force has room for improvement in Mike Tsukamoto 10 Strategy & Policy: addressing racial bias in the promotion process. The Big Fighter 33 Black Airmen Speak Out Contributors Gamble John T. Correll, By Rachel S. Cohen Robert S. Dudney, 12 Airframes Mark Gunzinger, In a force where color shouldn’t matter, inequalities 16 World: Rebuilding Jennifer Hlad, persist. Alyk Russell Kenlan, the forge; Meet the LaDonna Orleans new CMSAF; Space 37 The Goldfein Years Force organization; Russian Intercepts; By John A.