When Does Diffusing Protest Lead to Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia's Strategy for Influence Through Public Diplomacy

Journal of Strategic Studies ISSN: 0140-2390 (Print) 1743-937X (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjss20 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg To cite this article: Martin Kragh & Sebastian Åsberg (2017): Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case, Journal of Strategic Studies, DOI: 10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Published online: 05 Jan 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 32914 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fjss20 Download by: [Anna Lindh-biblioteket] Date: 21 April 2017, At: 02:48 THE JOURNAL OF STRATEGIC STUDIES, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2016.1273830 Russia’s strategy for influence through public diplomacy and active measures: the Swedish case Martin Kragha,b and Sebastian Åsbergc aHead of Russia and Eurasia Programme, Swedish Institute of International Affairs, Stockholm; bUppsala Centre for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden; cRussia and Eurasia Studies, Swedish Institute of International Affairs ABSTRACT Russia, as many contemporary states, takes public diplomacy seriously. Since the inception of its English language TV network Russia Today in 2005 (now ‘RT’), the Russian government has broadened its operations to include Sputnik news websites in several languages and social media activities. Moscow, however, has also been accused of engaging in covert influence activities – behaviour historically referred to as ‘active measures’ in the Soviet KGB lexicon on political warfare. -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

Communist Fight

Communist fight Journal of the Consistent Democrats Issue 5 Spring 2021 £2.50/£1 LCFI Manifesto May Day 2021 – the Working Class faces Pandemic, Depression, Wars and Global Heating. Capitalism must be overthrown! This year gone many billionaires doubled their wealth and 500 new ones emerged. While 150 million more pushed into extreme poverty. For May Day 2021 the people the world over have working class interna- come under concerted tionally faces the direst attack from neoliberalism, situation since the early the capitalist ideology that 1930s, and in some aimed to free monopoly cap- ways worse. Capitalism ital from all the restraints on is squeezing our class it resulting from a century of around the world from working class struggles and many directions. The gains, in the name of a ‘free Covid-19 Pandemic is a market’ which under todays result of capitalist de- concentrated, monopoly/ spoilation of the envi- corporate capitalism is a ronment and a terrible complete myth and lie. by- product of its wan- The destruction of a number ton exploitation of na- of so-called ‘Communist’ ture. Its apparent origin countries a generation ago: in China is no doubt a by-product of the commodification of which were in fact deformed workers states, damaged by- that society through capitalist restoration, but such despoila- products of the Russian and international workers’ struggles of tion of nature, which creates risks of spill-over biological 1917 onwards, has not led to a world of freedom and democ- events that can do enormous harm to humanity, are possible racy, “the End of History” as neoliberal ideologues such as in many places. -

Ukraine U.S./NATO-Backed Fascist Coup

Ukraine U.S./NATO-backed fascist coup & a growing people’s resistance $3.00 Table of Contents Article Page UKRAINE: What the media isn’t telling you 4 From an International Action Center fact sheet, March 2014 ‘The people continue to fight’ coup regime’s attack in Ukraine 6 By Greg Butterfield on April 11, 2014 Ukraine: People’s power vs. fascist repression 10 By Greg Butterfield on April 8, 2014 NO PHOTO U.S., EU strengthen grip on Ukraine 13 By Fred Goldstein on April 1, 2014 NO PHOTO Anti-fascists organize resistance as crisis grips Ukraine coup regime 17 By Greg Butterfield on March 28, 2014 2 PHOTOS Moscow rally supports Ukraine anti-fascists 22 By Greg Butterfield on March 27, 2014 1 PHOTO What a fascist video looks like 23 By Deirdre Griswold on March 26, 2014 NO PHOTO U.S. bombing of Serbia, after 15 years 25 By Sara Flounders on March 25, 2014 1 PHOTO Protests demand U.S. hands off Russia, Ukraine, Venezuela 26 By Kris Hamel on March 21, 2014 1 PHOTO plus 5 from prev week Ukraine crisis sets back NATO’s eastward advance 29 By Fred Goldstein on March 20, 2014 NO PHOTO Behind the coup in Ukraine: Oil and gas as a weapon 32 By Chris Fry on March 20, 2014 NO PHOTO U.S. hides Russian proposal to end crisis in Crimea 34 By Fred Goldstein on March 18, 2014 1 PHOTO (MAP) but added 1 NATO expansion—Yugoslavia to Ukraine 37 By Sara Flounders on March 18, 2014 1 PHOTO (MAP) Pro-West gangs attack Ukraine anti-fascists 42 By Greg Butterfield on March 18, 2014 1 PHOTO (with next article) Say no to another war! 45 By Editor on March 12, 2014 NO PHOTO (1 added) U.S. -

Zavadskaya Et Al Russia Electoral Authoritarian

Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 25: 4 (Fall 2017): 455-480 ELECTORAL SOURCES OF AUTHORITARIAN RESILIENCE IN RUSSIA: VARIETIES OF ELECTORAL MALPRACTICE, 2007-2016 MARGARITA ZAVADSKAYA EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY AT ST. PETERSBURG MAX GRÖMPING THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY FERRAN MARTINEZ I COMA GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Abstract: Elections do not always serve as instruments of democracy, but can successfully sustain modern forms of authoritarianism by maintaining political cooptation, signaling the regime’s invincibility, distributing rent among elites, and maintaining linkages with territorial communities. Russia exemplifies electoral practices adapted to the needs of authoritarian survival. Recent institutional reforms reflect the regime’s constant adjustment to emerging challenges. This study traces the evolution of the role of elections in Russia for ruling elites, the opposition, and parties. It argues that the information-gathering and co-optation functions of elections help sustain authoritarian rule, whereas insufficient co-optation and failure to signal regime strength may lead to anti-regime mobilization and Dr. Margarita Zavadskaya is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at the European University at Saint Petersburg and senior research fellow at the Laboratory for Comparative Social Research, Higher School of Economics (Russia). Contact: [email protected]. Dr. Max Grömping is Research Associate with the Department of Government and Interna- tional Relations, University of Sydney (Australia). Contact: [email protected]. Dr. Ferran Martínez i Coma is Research Fellow at the Centre for Governance and Public Policy and the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University, Brisbane (Australia). Contact: [email protected]. 455 456 Demokratizatsiya 25:4 (Fall 2017) weaken the regime. -

Managing Disorder Jérôme Roos 31 March 2014 When an Egyptian

Managing Disorder Jérôme Roos 31 March 2014 When an Egyptian judge condemned 529 Muslim Brotherhood supporters to death this week, he underlined in one fell swoop the terrifying reality in which the world finds itself today. The revolutionary euphoria and constituent impulse that shook the global order back in 2011 have long since given way to a re-established state of control. Violent repression of protest and dissent — whether progressive or reactionary — has become the new normal. The radical emancipatory and democratic space that was briefly opened up by recent uprisings is now being slammed shut. What remains are dispersed pockets of resistance under relentless assault by the constituted power. While the mass death sentence of Islamist protesters in Egypt is an exceptionally violent and lethal instance of this process, the army’s counter-revolutionary consolidation appears to be indicative of a more generalized trend that can be felt across the globe. In Turkey, Prime Minister Erdoðan — who back in 2011 criticized Mubarak for his hard- handed repression of the popular uprising — just blocked access to Twitter and YouTube. When a 15-year-old boy, Berkin Elvan, died after spending 9 months in a coma, having been shot in the head by police while getting some bread during the Gezi protests, Erdoðan justified the killing by branding the kid a “terrorist”. In Spain, meanwhile, the right-wing government of Mariano Rajoy is reverting to old-fashioned Francoist tactics to suppress the country’s powerful anti-austerity movement. Riot police once again violently cracked down on a massive demonstration in Madrid last weekend, while authorities are eagerly drawing on the new “Citizens’ Security Law” to prosecute the arrestees, some of whom now face up to 5 years in prison. -

Performing Political Opposition in Russia

2014:8 SOCIOLOGY PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL RESEARCH 2014:8 PERFORMING POLITICAL OPPOSITION IN RUSSIA RUSSIA IN OPPOSITION POLITICAL PERFORMING Russian civil society is often described as weak and Russians as politically apathetic. However, as a surprise for many, tens of thousands of people gathered on the streets of Moscow to protest the fraud in the parliamentary elections in December 2011. Nevertheless, this ‘awakening’ did not last for long as Vladimir Putin took hold of the Presidency again in 2012. Since then, the Russian State Duma has passed new legislation to restrict civic and political activism. This, together with the fragmentation of the opposition movement, has hindered large-scale and sustained mobiliza- tion against the government. In 2013, the number of protests has plummeted when the risks of demonstrating are high and the benefits to participate in political activism appear non-existent. Why is it impossible for the Russian opposition to find a common voice and to sustain contentious action? This book analyzes how political opportunities and restrictions in contem- porary Russia have affected the opposition activists’ activities at the grassroots level. The book examines Russian civil society, contemporary activist strategies, and democratization from the − THE CASE OF THE YOUTH MOVEMENT OBORONA OBORONA MOVEMENT YOUTH THE OF CASE THE perspective of the young activists participating in the liberal youth movement Oborona (Defense) in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Before its dissolution in 2011, Oborona was an active participant in the Russian opposition movement, and thus it is an interesting case study of the living activist traditions in Russia. The research illustrates how the Soviet continuities and liberal ideas are entangled in Russian political activism to create new post-socialist political identities and practices. -

“Systemic” and “Non-Systemic” Left in Contemporary Russia

“SYSTEMIC” AND “NON-SYSTEMIC” LEFT IN CONTEMPORARY RUSSIA MOSCOW 2019 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Alexandra Arkhipova graduated from the Historical-Philological Department of the Russian State University for the Humanities (RSUH). She got her PhD in philology from the RSUH in 2003, and now she is an associate professor at the RSUH’s Centre for Typological and Semiotic Folklore Studies. She also works as a senior researcher at the Research Laboratory for Theoretical Folklore Studies of the School of Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) and at the Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences. She is the author of over 100 articles and books on folkloristics and cultural anthropology, including Jokes about Stalin: Texts, Comments, Analysis (2009, in Russian; co-authored with M. Melnichenko) and Stirlitz went along the corridor: How we invent jokes (2013, in Russian). She co-edited (with Ya. Frukhtmann) the collection of articles Fetish and Taboo: Anthropology of Money in Russia (2013) and Mythological Models and Ritual Behaviour in the Soviet and Post-Soviet Sphere (2013). She has been studying protests in Russia since 2011. She edited a multi-author book We Are Not Mute: Anthropology of Protest in Russia (2014). Ekaterina Sokirianskaia graduated from the Department of Foreign Languages of the Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia (Herzen University) and completed her postgraduate study at the Department of Philosophy of the St. Petersburg State University. She holds Master’s and PhD degrees in political science from the Central European University. She is the director at the Conflict Analysis and Prevention Centre. -

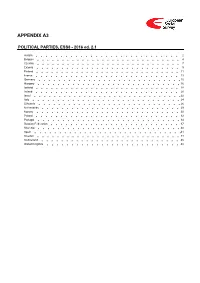

ESS8 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS8 - 2016 ed. 2.1 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Czechia 7 Estonia 9 Finland 11 France 13 Germany 15 Hungary 16 Iceland 18 Ireland 20 Israel 22 Italy 24 Lithuania 26 Netherlands 29 Norway 30 Poland 32 Portugal 34 Russian Federation 37 Slovenia 40 Spain 41 Sweden 44 Switzerland 45 United Kingdom 48 Version Notes, ESS8 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS8 edition 2.1 (published 01.12.18): Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. ESS8 edition 2.0 (published 30.05.18): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Portugal, Spain. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2013 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ), Social Democratic Party of Austria, 26,8% names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP), Austrian People's Party, 24.0% election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ), Freedom Party of Austria, 20,5% 4. Die Grünen - Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne), The Greens - The Green Alternative, 12,4% 5. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ), Communist Party of Austria, 1,0% 6. NEOS - Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum, NEOS - The New Austria and Liberal Forum, 5,0% 7. Piratenpartei Österreich, Pirate Party of Austria, 0,8% 8. Team Stronach für Österreich, Team Stronach for Austria, 5,7% 9. Bündnis Zukunft Österreich (BZÖ), Alliance for the Future of Austria, 3,5% Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

What Is Left of Leninism? New European Left Parties in Historical Perspective

WHAT IS LEFT OF LENINISM? NEW EUROPEAN LEFT PARTIES IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE CHARLES POST oday, the socialist left in Europe confronts a situation markedly Tdifferent from most of the twentieth century. The social democratic parties, while maintaining significant electoral support among workers in most of Europe, are no longer parties of even pro-working-class reform. Most have adapted ‘social liberal’ politics, combining residual rhetoric about social justice with the implementation of a neoliberal economic and social programme of privatization, austerity and attacks on organized labour. The communist parties, with few exceptions, have either disappeared or are of marginal electoral and political weight. They were unable to survive either the collapse of the bureaucratic regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, or over four decades as the junior partners in electoral alliances with a rightward moving social democracy. The European socialist left that has survived is attempting to create new forms of organization. While some of these parties have labeled themselves ‘anti-capitalist’ and others ‘anti- neoliberal’, almost all of these parties describe themselves as both ‘post-social democratic’ and ‘post-Leninist’.1 Striving to create forms of working-class and popular political representation for a new era, many in these parties claim to be transcending the historic divide in the post-1917 socialist movement. This essay seeks to lay the historical foundation for a better understanding of the extent to which these parties have actually moved beyond the main currents of twentieth century socialism. We start with a reexamination of the theory and history of pre-First World War social democracy, and examine what Leninism represented in relation to it. -

Constructing Revolution: Soviet Propaganda Posters from Between the World Wars September 24, 2017–February 11, 2018

Constructing Revolution: Soviet Propaganda Posters from between the World Wars September 24, 2017–February 11, 2018 Bowdoin College Museum of Art OSHER GALLERY Constructing Revolution: Soviet Propaganda Posters from between the World Wars Constructing Revolution explores the remarkable and wide-ranging body of propaganda posters as an artistic consequence of the 1917 Russian Revolution. Marking its centennial, this exhibition delves into a relatively short-lived era of unprecedented experimentation and utopian idealism, which produced some of the most iconic images in the history of graphic design. The eruption of the First World War, the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, and the subsequent civil war broke down established political and social structures and brought an end to the Tsarist Empire. Russia was split into antagonistic worlds: the Bolsheviks and the enemy, the proletariat and the exploiters, the collective and the private, the future and the past. The deft manipulation of public opinion was integral to the violent class struggle. Having seized power in 1917, the Bolsheviks immediately recognized posters as a critical means to tout the Revolution’s triumph and ensure its spread. Posters supplied the new iconography, converting Communist aspirations into readily accessible, urgent, public art. This exhibition surveys genres and methods of early Soviet poster design and introduces the most prominent artists of the movement. Reflecting the turbulent and ultimately tragic history of Russia in the 1920s and 1930s, it charts the formative decades of the USSR and demonstrates the tight bond between Soviet art and ideology. All works in this exhibition are generously lent by Svetlana and Eric Silverman ’85, P’19.