Bill Talen and Reverend Billy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Words, No Problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8Pm, Upfront Theatre

THE GRISTLE, P.06 + ORCHARD OUTING, P.14 + BEER WEEK, P.30 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM SKAGIT ISLAND COUNTIES 04-25-2018* • ISSUE:*17 • V.13 PIPELINE PROTESTS Protecting the Salish Sea, P.08 SKAGIT STOP Art at the schoolhouse, P.16 MARK LANEGAN A post- Celebrate AGI grunge SK T powerhouse, P.18 No words, no problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8pm, Upfront Theatre Paula Poundstone: 8pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount 30 A brief overview of this Vernon Backyard Brawl: 10pm, Upfront Theatre FOOD week’s happenings THISWEEK DANCE Contra Dance: 7-10:30pm, Fairhaven Library 24 MUSIC Dylan Foley, Eamon O’Leary: 7pm, Littlefield B-BOARD Celtic Center, Mount Vernon Skagit Symphony: 7:30pm, McIntyre Hall, Mount Vernon 23 WORDS FILM Book and Bake Sale: 10am-5pm, Deming Library Naomi Shihab Nye: 7pm, Performing Arts Center, Politically powered standup WWU 18 comedian Hari Kondabolu COMMUNITY MUSIC Vaisaikhi Day Celebration: 10am-5pm, Guru Nanak stops by Bellingham for an April Gursikh Gurdwaram, Lynden 16 GET OUT ART 29 gig at the Wild Buffalo Have a Heart Run: 9am, Edgewater Park, Mount Vernon 15 Everson Garden Club Sale: 9am-1pm, Everson- Goshen Rd. Native Flora Fair: 10am-3pm, Fairhaven Village STAGE Green 14 FOOD Pancake Breakfast: 8-10am, American Legion Hall, Ferndale GET OUT Pancake Breakfast: 8-10:30am, Lynden Community Center Bellingham Farmers Market: 10am-3pm, Depot 12 Market Square WORDS VISUAL Roger Small Reception: 5-7pm, Forum Arts, La WEDNESDAY [04.25.18] Conner 8 Spring has Sprung Party: 5-9pm, Matzke Fine Art MUSIC Gallery, Camano Island F.A.M.E. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

East Bay Deputy Held in Drug Case Arrest Linked to Ongoing State Narcotics Agent Probe

Sunday, March 6, 2011 California’s Best Large Newspaper as named by the California Newspaper Publishers Association | $3.00 Gxxxxx• TOP OF THE NEWS Insight Bay Area Magazine WikiLeaks — 1 Newsom: Concerns Spring adventure World rise over S.F. office deal 1 Libya uprising: Reb- How Europe with donor. C1 tours from the els capture a key oil port caves in to U.S. 1 Shipping: Nancy Pelo- Galapagos to while state forces un- si extols the importance leash mortar fire. A5 pressure. F6 of local ports. C1 South Africa. 6 Sporting Green Food & Wine Business Travel 1 Scouting triumph: 1 Larry Goldfarb: Marin The Giants picked All about falafel County hedge fund manager Special Hawaii rapidly rising prospect who settled fraud charges Brandon Belt, right, — with three stretched the truth about section touts 147th in the ’09 draft. B1 recipes. H1 charitable donations. D1 Kailua-Kona. M1 RECOVERY East Bay deputy held in drug case Arrest linked to ongoing state narcotics agent probe By Justin Berton custody by agents representing CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER the state Department of Justice and the district attorney’s of- A Contra Costa County sher- fice. iff’s deputy has been arrested in Authorities did not elaborate connection with the investiga- on the details of the alleged tion of a state narcotics agent offenses, but a statement from who allegedly stole drugs from the Contra Costa County Sher- Michael Macor / The Chronicle evidence lockers, authorities iff’s Department said Tanabe’s Chris Rodriguez (4) of the Bay Cruisers shoots over Spencer Halsop (24) of the Utah Jazz said Saturday. -

Page 1 of 3 Citigroup Gets a Monetary Lifeline from Feds 11/25/2008 Http

Citigroup gets a monetary lifeline from feds Page 1 of 3 home of the Home Delivery | Today's Paper | Ads nmlkji SFGate nmlkj Web Search by YAHOO! | Advanced Search Sign In | Register Technology Markets Small Business Chron 200 Real Estate Net Worth - Kathleen Pender Archive | E-mail | Citigroup gets a monetary lifeline from feds Kathleen Pender Tuesday, November 25, 2008 PRINT E-MAIL SHARE COMMENTS (18) FONT | SIZE: The bailouts keep coming, and they seem to be getting worse for taxpayers. The deal worked out over the weekend to prevent the collapse of Citigroup "is a terrible deal for taxpayers," says Campbell Harvey, a Duke University global finance professor. "Some intervention was necessary. But the terms of the intervention basically shafted the 1. Prop. 8 backers splinter as court fight resumes U.S. taxpayer." 2. California to investigate Mormon aid to Prop 8 Analysts at CreditSights estimate the government could 3. Planners to consider S.F. congestion charge IMAGES lose up to $230 billion on the assets, but expect actual 4. Obama names top economic advisers 5. Gay-rights activists protest Prop. 8 at Capitol losses "would be significantly less." 6. The ugly backlash over Proposition 8 7. Government plans massive Citigroup rescue Under the deal, the U.S. government will invest $20 effort billion in Citigroup preferred stock (on top of its previous $25 billion capital injection from the Troubled Asset Relief Program) and guarantee up to $306 billion in mortgage and other assets. PLANNING Make a Difference in our Future! View Larger Image Citigroup would absorb the first $29 billion in losses on Kern County Water Agency that asset pool, which would remain on Citigroup's NET WORTH balance sheet but be "ring fenced" or segregated. -

Rosalie Sorrelssorrels AA Voicevoice Likelike Finefine Winewine

GET A CATAMOUNT COLLECTIVE SAMPLER FREE! (SEE INSERT FOR DETAILS!) Vol. 48 No. 2 Summer 2004 RobinRobin && LindaLinda WilliamsWilliams TheirTheir GroupGroup IsIs FineFine TownesTownes VanVan ZandtZandt AmericanAmerican SongwritingSongwriting MineMine RosalieRosalie SorrelsSorrels AA VoiceVoice LikeLike FineFine WineWine TheThe DiscoveryDiscovery StringString BandBand Tracking Lewis & Clark EllikaEllika && SoloSolo MeldingMelding SwedenSweden && AfricaAfrica Robin & Linda HaugaardHaugaard Williams && HøirupHøirup Danish Duo PLUS:PLUS: 2 SongsSongs 4 Teach-InsTeach-Ins 5 ColumnsColumns 1 FestivalsFestivals ReviewsReviews NewsNews 50690793 $6.95 USA / $10.00 CAN £4.75 UK 69 Photo by Cass Fine © Rosalie Sorrels: Passing the Good Stuff On BY DAVID KUPFER “She’s the salt of the earth though it was her interest in the early songs of the Mormon pioneers that inspired her to become one of our community’s Straight from the bosom of the Mormon great folk singers. church Rosalie Sorrels is truly a national treasure, a master storyteller, a respected folklorist, and a legendary travel- With a voice like wine ing diva who possesses a rich, wise voice that flows straight from heart to mouth. Idaho-born and raised, Cruisin’ along in that Ford Econoline ... ” Rosalie is soft-spoken, shy and unassuming with a hand- some face and a warm smile. She wears a slight Midwest- — Nanci Griffith, “Ford Econoline” ern twang, delightful laugh and lively sense of humor. But it is Rosalie’s strong sense of self-reliance that has be- ith her song “Ford Econoline,” Nanci Griffith come the trademark of her contribution to the American chronicled the life of a single mother who packed folk landscape ... and her ability to sing songs about and W up her kids to tour around the country as a folk to those she loves in a wholly unique way that has made singer. -

Ningún Ser Humano Es Ilegal!

No Human Is Illegal: ¡Ningún Ser Humano es Ilegal! immigrantsolidarity.org An Educator’s Guide for Addressing Immigration in the Classroom New York Collective of Radical Educators http://www.nycore.org April 2006 New York Collective of Radical Educators (NYCoRE) NYCoRE is a group of public school educators committed to fighting for social justice in our school system and society at large, by organizing and mobilizing teachers, developing curriculum, and working with community, parent, and student organizations. We are educators who believe that education is an integral part of social change and that we must work both inside and outside the classroom because the struggle for justice does not end when the school bell rings. http://www.nycore.org [email protected] To join the NYCoRE listserv, send email to [email protected] Table of Contents 1. How To Use This Guide……………………………………………………...…….…P. 2 2. NYCoRE’s Recommendations and Statement in English and Spanish..…… P. 3 3. Participate with NYCoRE in the May 1st Great American Boycott……..….…..P. 4 4. Encourage and Protect Students who Organize and Participate…… ………P. 5 a. Recent Press about Student Walkouts………………………….…………….P. 5 b. Know Your Students’ Rights……………………………………………………P. 6 5. Connect your Activism to Your Academics……………………………….………P. 7 a. The Proposed Legislation HR 4437……………………………………………P. 7 b. Organizing Responses…………………………………………………………..P. 8 c. Curricular Materials and Resources……………………………………………P. 10 6. New York City Resources……………………………..………………………………P. 11 How To Use This Guide This guide is most useful when used online, as opposed to a paper copy. Most of the resources in this guide are web- based links, so if viewed online, just click on the links. -

'I Mn,Hurxicane" There's a Hurricane , Coming to Your Town!

NICKEL -BACK IN ACTION J . Nickelback's FORMAT FOCUS: Get-Dut-The-Vote Drives, On -site And Street Cove-age Return 'Gotta Pre Radio For Election 2CC8 Be Somebody' pp.16w 32, 46, 31, 54 Pounces On CHR /Top 40, Canadian P. o Is Live, Loca -And Reaping The Rewards Hot AC, Rock, Active Rock & Alternative After INTERACTIVE: Quin Fly :Est Offer First Airplay Week PLUS: New Multiplatform Radic Apps Brad Paisley's 'Side' Project RADIO & RECORDS PROFILE: Greater MeciE's He di Proves Instrumental Raphael OCTOBER 10 200E ND 1783 $6.50 www.FadioandRecordsan .aDVERTISEMEN- 'i_mn,Hurxicane" there's A Hurricane , Coming To Your town! Call NOW For An Interview With Sharmian. Time to Have Some Drive Time F -U -N!! 615-506-9198 Sharmian @gmail.com Nashville 615-506-9198 i myspace.com /Sharmian Reyna@trevi noenterpri ses. ne Contact L.A. 818 -660 -2888 Thanks Country Radìo..Keep on spinning "I Drank Myself To ßêd"! www.americanradiohistory.com America's nett smash. From America's favorite Idol. 04 ofe--/ rip II K iginal and savvy male finalist in the show's history." - NEW TIMES myspate.com/officialdavidcook Ilf RCA RECORDS IABEI IS AKINN Of SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT INN(S) Q) RCGISTERED. poa. MARCAIS) REGISTRAOATS) RCA 1RADF:MARK MANACT 80 N1 SA. BMG LOGO IS A TRADEMARK OF BERTEISMANN MUSIC GROUP. INC. Qa 2008 RCA RI. CORDS, A UNIT Of SONY BMG MUSIC ENTERTAIN/8f NE www.americanradiohistory.com WWW.RADIOANDRECORDS.COM: INDUSTRY AND FORMAT NEWS, AS IT HAPPENS, AROUND THE CLOCK. RAR NewsFocs Pennington Promoted Legal Fireworks Continue Over ON THE WEl3 To WRIF PD Cell Phone -Only Sampling Accelerated For Diaries Greater Media/Detroit PPM Commercialization promotes active rock In a niove crafted to pre -empt any attempt to block the rollout of its embattled PPM rat- Responding to pressure by the Radio WRIF APD /MD Mark ings, Arbitron on Oct. -

The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-5-2018 News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Higgins-Dobney, Carey Lynne, "News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4410. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6307 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. News Work: The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting by Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Studies Dissertation Committee: Gerald Sussman, Chair Greg Schrock Priya Kapoor José Padín Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney News Work i Abstract By virtue of their broadcast licenses, local television stations in the United States are bound to serve in the public interest of their community audiences. As federal regulations of those stations loosen and fewer owners increase their holdings across the country, however, local community needs are subjugated by corporate fiduciary responsibilities. Business practices reveal rampant consolidation of ownership, newsroom job description convergence, skilled human labor replaced by computer automation, and economically-driven downsizings, all in the name of profit. -

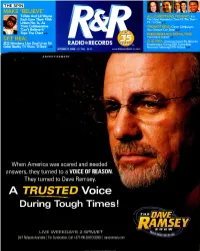

A TRUSTED Voice

THE SPIN MAKE 'BELIEVE' T Pain And LiI Wayne A MAS FORMAT: It's Each Earn Their Fifth The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year - Urban No. ls, As Til -'s Over Their Collaborative PROMOTIONS: Clever Campaigns 'Can't Believe It' You Station Can Steal Tops The Chart PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES: The Global Ir,pact GET ; THE PPM: Concerns Raised By Minority 302 Members Live Dual Lives On RADIO & RECORDS Broadcasters During R &R Conve -rtion Cable Reality TV Show 'Z Rock' Resonate Following PPM Rollout OCTOBER 17, 2008 NO. 1784 $6.EO www.RadioandRecc -c s.com ADVERTISEMENT When America was scared and needed nswers, they turned to a VOICE OF REASON. They turned to Dave Ramsey. A TRUSTED Voice During Tough Times! 7 /THEDAVÊ7 C AN'S HOW Ey LIVE WEEKDAYS 2-5PM/ET 0?e%% aáens caller aller cal\e 24/7 Re-eeds Ava lable For Syndication, Call 1- 877 -410 -DAVE (32g3) daveramsey.com www.americanradiohistory.com National media appearances When America was scared and needed focused on the economic crisis: answers, they turned to a voice Your World with Neil Cavuto (5x) of reason. They turned to Dave Ramsey. Fox Business' Happy Hour (3x) The O'Reilly Factor Fox Business with Dagen McDowell and Brian Sullivan Fox Business with Stuart Varney (5x) Fox Business' Bulls & Bears (2x) America's Nightly Scoreboard (2x) Larry King Live (3x) Fox & Friends (7x) Geraldo at Large (2x) Good Morning America (3x) Nightline The Early Show Huckabee The Morning Show with Mike and Juliet (3x) Money for Breakfast Glenn Beck Rick & Bubba (3x) The Phil Valentine Show and serving our local affiliates: WGST Atlanta - Randy Cook KTRH Houston - Michael Berry KEX Portland - The Morning Update with Paul Linnman WWTN Nashville - Ralph Bristol KTRH Houston - Morning News with Lana Hughes and J.P. -

Reviewers' Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher's Religulous

Boise State University ScholarWorks Communication Faculty Publications and Department of Communication Presentations 4-1-2011 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media and Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media and Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media & Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media & Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University Abstract This paper examines reviewers’ reactions to Bill Maher’s documentary film Religulous as a way of beginning a discussion of media and religious hegemony. Hegemony theory posits that dominant ideology typically trumps contesting views, even when the latter do manage to leak through the system. Given this, one might expect that film reviewers serve as a second line of defense for entrenched worldviews. Here, however, a thematic analysis of reviews from major national newspapers reveals that critics provided only slight support to traditional religious views Maher challenges in his filmic plea for agnosticism. There is in the world of comedy a plot structure that has traditionally been referred to with the non-inclusive label, “Character gets hoisted with his own petard.” Most of us can envision this element by remembering the classic Warner Brothers Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons. -

Detroit Tues, July 29, 1975 from Detroit News 2 WJBK-CBS * 4 WWJ-NBC * 7 WXYZ-ABC * 9 CBET-CBC

Retro: Detroit Tues, July 29, 1975 from Detroit News 2 WJBK-CBS * 4 WWJ-NBC * 7 WXYZ-ABC * 9 CBET-CBC (and some CTV) * 20 WXON-Ind * 50 WKBD-Ind * 56 WTVS-PBS [The News didn't list TVO, Global or CBEFT] Morning 6:05 7 News 6:19 2 Town & Country Almanac 6:25 7 TV College 6:30 2 Summer Semester 4 Classroom 56 Varieties of Man & Society 6:55 7 Take Kerr 7:00 2 News (Frank Mankiewicz) 4 Today (Barbara Walters/Jim Hartz; Today in Detroit at 7:25 and 8:25) 7 AM America (Bill Beutel) 56 Instructional TV 7:30 9 Cartoon Playhouse 8:00 2 Captain Kangaroo 9 Uncle Bobby 8:30 9 Bozo's Big Top 9:00 2 New Price is Right 4 Concentration 7 Rita Bell "Miracle of the Bells" (pt 2) 9:30 2 Tattletales 4 Jackpot 9 Mr. Piper 50 Jack LaLanne 9:55 4 Carol Duvall 10:00 2 Spin-Off 4 Celebrity Sweepstakes 9 Mon Ami 50 Detroit Today 56 Sesame Street 10:15 9 Friendly Giant 10:30 2 Gambit 4 Wheel of Fortune 7 AM Detroit 9 Mr. Dressup 50 Not for Women Only 11:00 2 Phil Donahue 4 High Rollers 9 Take 30 from Ottawa 50 New Zoo Revue 56 Electric Company 11:30 4 Hollywood Squares 7 Brady Bunch 9 Family Court 50 Bugs Bunny 56 Villa Alegre Afternoon Noon 2 News (Vic Caputo/Beverly Payne) 4 Magnificent Marble Machine 7 Showoffs 9 Galloping Gourmet 50 Underdog 56 Mister Rogers' Neighborhood 12:30 2 Search for Tomorrow 4 News (Robert Blair) 7 All My Children 9 That Girl! 50 Lucy 56 Erica-Theonie 1:00 2 Love of Life (with local news at 1:25) 4 What's My Line? 7 Ryan's Hope 9 Showtime "The Last Chance" 50 Bill Kennedy "Hell's Kitchen" 56 Antiques VIII 1:30 2 As the World Turns 4 -

Chapter 1—Introduction

NOTES CHAPTER 1—INTRODUCTION 1. See Juan Flores, “Rappin’, Writin’ & Breakin,’” Centro, no. 3 (1988): 34–41; Nelson George, Hip Hop America (New York: Viking, 1998); Steve Hager, Hip Hop: The Illustrated History of Breakdancing, Rapping and Graffiti (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984); Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1994); David Toop, The Rap Attack 2: African Rap to Global Hip Hop (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1991). 2. Edward Rodríguez, “Sunset Style,” The Ticker, March 6, 1996. 3. Carlito Rodríguez, “The Young Guns of Hip-Hop,” The Source 105 ( June 1998): 146–149. 4. Clyde Valentín, “Big Pun: Puerto Rock Style with a Twist of Black and I’m Proud,” Stress, issue 23 (2000): 48. 5. See Juan Flores, Divided Borders: Essays on Puerto Rican Identity (Hous- ton: Arte Público Press, 1993); Bonnie Urciuoli, Exposing Prejudice: Puerto Rican Experiences of Language, Race and Class (Boulder, CO: West- view Press, 1996). 6. See Manuel Alvarez Nazario, El elemento afronegroide en el español de Puerto Rico (San Juan: Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña,1974); Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cam- bridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993); Marshall Stearns, The Story of Jazz (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958); Robert Farris Thompson, “Hip Hop 101,” in William Eric Perkins, ed., Droppin’ Sci- ence: Critical Essays on Rap Music and Hip Hop Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), pp. 211–219; Carlos “Tato” Torres and Ti-Jan Francisco Mbumba Loango, “Cuando la bomba ñama...!:Reli- gious Elements of Afro-Puerto Rican Music,” manuscript 2001.