Reviewers' Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher's Religulous

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Words, No Problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8Pm, Upfront Theatre

THE GRISTLE, P.06 + ORCHARD OUTING, P.14 + BEER WEEK, P.30 c a s c a d i a REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM SKAGIT ISLAND COUNTIES 04-25-2018* • ISSUE:*17 • V.13 PIPELINE PROTESTS Protecting the Salish Sea, P.08 SKAGIT STOP Art at the schoolhouse, P.16 MARK LANEGAN A post- Celebrate AGI grunge SK T powerhouse, P.18 No words, no problem, P.15 Genre Legends: 8pm, Upfront Theatre Paula Poundstone: 8pm, Lincoln Theatre, Mount 30 A brief overview of this Vernon Backyard Brawl: 10pm, Upfront Theatre FOOD week’s happenings THISWEEK DANCE Contra Dance: 7-10:30pm, Fairhaven Library 24 MUSIC Dylan Foley, Eamon O’Leary: 7pm, Littlefield B-BOARD Celtic Center, Mount Vernon Skagit Symphony: 7:30pm, McIntyre Hall, Mount Vernon 23 WORDS FILM Book and Bake Sale: 10am-5pm, Deming Library Naomi Shihab Nye: 7pm, Performing Arts Center, Politically powered standup WWU 18 comedian Hari Kondabolu COMMUNITY MUSIC Vaisaikhi Day Celebration: 10am-5pm, Guru Nanak stops by Bellingham for an April Gursikh Gurdwaram, Lynden 16 GET OUT ART 29 gig at the Wild Buffalo Have a Heart Run: 9am, Edgewater Park, Mount Vernon 15 Everson Garden Club Sale: 9am-1pm, Everson- Goshen Rd. Native Flora Fair: 10am-3pm, Fairhaven Village STAGE Green 14 FOOD Pancake Breakfast: 8-10am, American Legion Hall, Ferndale GET OUT Pancake Breakfast: 8-10:30am, Lynden Community Center Bellingham Farmers Market: 10am-3pm, Depot 12 Market Square WORDS VISUAL Roger Small Reception: 5-7pm, Forum Arts, La WEDNESDAY [04.25.18] Conner 8 Spring has Sprung Party: 5-9pm, Matzke Fine Art MUSIC Gallery, Camano Island F.A.M.E. -

Sociology of Religion, Lundscow, Chapter 7, Cults

Sociology of Religion , Sociology 3440-090 Summer 2014, University of Utah Dr. Frank J. Page Office Room 429 Beh. Sci., Office Hours: Thursday - Friday, Noon – 4:00-pm Office Phone: (801) 531-3075 Home Phone: (801) 278-6413 Email: [email protected] I. Goals: The primary goal of this class is to give students a sociological understanding of religion as a powerful, important, and influential social institution that is associated with many social processes and phenomena that motivate and influence how people act and see the world around them. The class will rely on a variety of methods that include comparative analysis, theoretical explanations, ethnographic studies, and empirical studies designed to help students better understand religion and its impact upon societies, global-international events, and personal well-being. This overview of the nature, functioning, and diversity of religious institutions should help students make more discerning decisions regarding cultural, political, and moral issues that are often influenced by religion. II. Topics To Be Covered: The course is laid out in two parts. The first section begins with a review of conventional and theoretical conceptions of religion and an overview of the importance and centrality of religion to human societies. It emphasizes the diversity and nature of "religious experience" in terms of different denominations, cultures, classes, and individuals. This is followed by overview of sociological assumptions and theories and their application to religion. A variety of theoretical schools including, functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory, sociology of knowledge, sociobiology, feminist theory, symbolic interactionism, postmodern and critical theory will be addressed and applied to religion. -

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

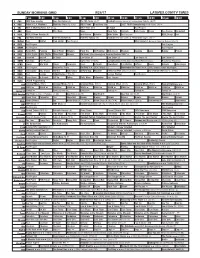

Sunday Morning Grid 9/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Houston Texans at New England Patriots. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Presidents Cup 2017 TOUR Championship Final Round. (N) Å 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Rock-Park Outback Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football New York Giants at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program MLS Soccer LA Galaxy at Sporting Kansas City. (N) 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Cooking Jazzy Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons DW News: Live Coverage of German Election 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana The Reef ›› (2006, Niños) (G) Remember the Titans ››› (2000, Drama) Denzel Washington. -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

![<R2PX] 2^]Rtstb <XRWXVP]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2984/r2px-2-rtstb-xrwxvp-492984.webp)

<R2PX] 2^]Rtstb <XRWXVP]

M V 7>DB4>540AC7)Get a chic blueprint with no carbon footprint | 8]bXST A PUBLICATION OF | P L A N Y O U R N I G H T A T W W W. E X P R E S S N I G H T O U T. C O M | OCTOBER 3-5, 2008 | -- 5A44++ Weekend C74A>03F0AA8>AB --;Pbc]XVWc½bSTQPcTT]STSPUcTa C74A43B:8=B4G?42C0C>D675867C8=?78;;Hk ! 4g_aTbb½STPS[X]T5X]SX]ST_cW R^eTaPVTPcfPbWX]Vc^]_^bcR^\ <R2PX] 2^]RTSTb CHRIS O’MEARA/AP Evan Longoria hit two home runs in the Rays’ win. <XRWXVP] APhbA^[[)Longoria powers Losing ground, Republican Tampa to first playoff win | # writes off battleground state F0B78=6C>=k Republican presidential can- ATbRdT4UU^ac) Push to get didate John McCain conceded battleground Michigan to the Democrats on Thursday, GOP bailout passed gains steam | " officials said, a major retreat as he struggles to regain his footing in a campaign increas- 5^bbTcc2[dTb) Wreckage of ingly dominated by economic issues. These officials said McCain was pulling adventurer’s plane found | # staff and advertising out of the economically distressed Midwestern state. With 17 elec- 4=C4AC08=<4=C toral votes, Michigan voted for Democrat John Kerry in 2004, but Republicans had poured money into an effort to try to place it in their column this year. ?[PhX]V=XRT) The decision allows McCain’s resources Michael Cera acts to be sent to Ohio, Wisconsin, Florida and other more competitive states. But it also sweetly awk- means Obama can shift money to other ward .. -

East Bay Deputy Held in Drug Case Arrest Linked to Ongoing State Narcotics Agent Probe

Sunday, March 6, 2011 California’s Best Large Newspaper as named by the California Newspaper Publishers Association | $3.00 Gxxxxx• TOP OF THE NEWS Insight Bay Area Magazine WikiLeaks — 1 Newsom: Concerns Spring adventure World rise over S.F. office deal 1 Libya uprising: Reb- How Europe with donor. C1 tours from the els capture a key oil port caves in to U.S. 1 Shipping: Nancy Pelo- Galapagos to while state forces un- si extols the importance leash mortar fire. A5 pressure. F6 of local ports. C1 South Africa. 6 Sporting Green Food & Wine Business Travel 1 Scouting triumph: 1 Larry Goldfarb: Marin The Giants picked All about falafel County hedge fund manager Special Hawaii rapidly rising prospect who settled fraud charges Brandon Belt, right, — with three stretched the truth about section touts 147th in the ’09 draft. B1 recipes. H1 charitable donations. D1 Kailua-Kona. M1 RECOVERY East Bay deputy held in drug case Arrest linked to ongoing state narcotics agent probe By Justin Berton custody by agents representing CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER the state Department of Justice and the district attorney’s of- A Contra Costa County sher- fice. iff’s deputy has been arrested in Authorities did not elaborate connection with the investiga- on the details of the alleged tion of a state narcotics agent offenses, but a statement from who allegedly stole drugs from the Contra Costa County Sher- Michael Macor / The Chronicle evidence lockers, authorities iff’s Department said Tanabe’s Chris Rodriguez (4) of the Bay Cruisers shoots over Spencer Halsop (24) of the Utah Jazz said Saturday. -

Page 1 of 3 Citigroup Gets a Monetary Lifeline from Feds 11/25/2008 Http

Citigroup gets a monetary lifeline from feds Page 1 of 3 home of the Home Delivery | Today's Paper | Ads nmlkji SFGate nmlkj Web Search by YAHOO! | Advanced Search Sign In | Register Technology Markets Small Business Chron 200 Real Estate Net Worth - Kathleen Pender Archive | E-mail | Citigroup gets a monetary lifeline from feds Kathleen Pender Tuesday, November 25, 2008 PRINT E-MAIL SHARE COMMENTS (18) FONT | SIZE: The bailouts keep coming, and they seem to be getting worse for taxpayers. The deal worked out over the weekend to prevent the collapse of Citigroup "is a terrible deal for taxpayers," says Campbell Harvey, a Duke University global finance professor. "Some intervention was necessary. But the terms of the intervention basically shafted the 1. Prop. 8 backers splinter as court fight resumes U.S. taxpayer." 2. California to investigate Mormon aid to Prop 8 Analysts at CreditSights estimate the government could 3. Planners to consider S.F. congestion charge IMAGES lose up to $230 billion on the assets, but expect actual 4. Obama names top economic advisers 5. Gay-rights activists protest Prop. 8 at Capitol losses "would be significantly less." 6. The ugly backlash over Proposition 8 7. Government plans massive Citigroup rescue Under the deal, the U.S. government will invest $20 effort billion in Citigroup preferred stock (on top of its previous $25 billion capital injection from the Troubled Asset Relief Program) and guarantee up to $306 billion in mortgage and other assets. PLANNING Make a Difference in our Future! View Larger Image Citigroup would absorb the first $29 billion in losses on Kern County Water Agency that asset pool, which would remain on Citigroup's NET WORTH balance sheet but be "ring fenced" or segregated. -

Chef Catherine Blake Presented “Cooking for Brain Power”

The Island Vegetarian Vegetarian Society of Hawaii Quarterly Newsletter Inside This Issue Time to Celebrate! VSH Pre-Thanksgiving Dinner 1,3 VSH’s Pre-Thanksgiving Mahalo to Our VSH Volunteers 2 Top Cardiologist Eats Vegan 3 Dinner on Novembef 21 Animal Protein & Osteoporosis 4 Tasty & Meatless at ShareFest 5 Vegan Foodies Club-Sushi Rolls 6-7 Nutrition News 7 If the Oceans Die, We Die 8 Oahu and Maui VSH Events 8,9 Kauai VSH Events 10 Cowspiracy 11 by Karl Seff, PhD Fermentation 12 VSH Board member Heart Healthy Recipe 13 Our Daily Food Choices Matter 14 Upcoming Events 15-18 Membership Benefits 19 Our year-end holidays begin each year with VSH’s annual vegan Pre- Thanksgiving Dinner! This year it will be at McCoy Pavilion at Ala Moana Beach Park, 1201 Ala Moana Boulevard, in Honolulu, and, like last year, it will be on the Friday before Thanksgiving, November 21, 2014. Free Public Lectures As in recent years, Madana Sundari will be preparing a full Thanksgiving vegan buffet for us. Wherever possible, it will be organic and free of GMOs, T. Colin Campbell, PhD hydrogenated oils, MSG, preservatives, and artificial colors and flavors. Open “Nutrition Is Far More Effective to VSH members and non-members, from vegans to non-vegetarians, a record Than Generally Known” high of about 340 people attended last year’s dinner, held at Govinda’s. Tuesday, October 14, 2014 The fare will be very traditional (see the menu on page 3), and entirely home- Ala Wai Golf Course Clubhouse made. Expect a comfortable, quiet Thanksgiving experience. -

Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best

12 | THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best The HSUS President & CEO Wayne Pacelle, actor James Cromwell, and Joan McIntosh. Genesis Awards founder Gretchen Wyler. he power of the media to project the joy of celebrating animals Wyler came up with the idea for an awards show because she strongly Tand to promote their humane treatment was demonstrated believed that honoring members of the media encourages them to anew at the 20th Anniversary HSUS Genesis Awards staged before spotlight more animal issues, thus increasing public awareness and a glittering audience at California’s Beverly Hilton Hotel in March. compassion. The annual event began as a luncheon with 140 attendees The ceremonies presented awards in 21 print, television, and film and quickly grew into a large gala in Beverly Hills, California, with categories and honored dozens of talented individuals from news more than 1,000 guests. and entertainment media. Beginning with the first ceremony, Genesis Awards entries have The annual celebration recaptured some of the extraordinary events been submitted by the public and by media professionals. Categories that occurred in 2005, from the massive effort to rescue animals span television, film, print, radio, music, and the arts. The awards abandoned in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to such perennial committee chooses winners by secret ballot and the 17 committee concerns as fur, factory farming, and wildlife abuses. It also marked members are selected because of their lengthy personal histories the retirement of HSUS Vice President Gretchen Wyler, who founded in working for the animals. -

Charging Forward for Animals

2006 HSUS Annual Report Celebrating Animals | Confronting Cruelty Charging Forward for Animals R59542.indd C1 5/22/07 14:14:27 Offi cers Directors David O. Wiebers, M.D. Leslie Lee Alexander, Esq. Chair of the Board Patricia Mares Asip Anita W. Coupe, Esq. Peter A. Bender Vice Chair of the Board Barbara S. Brack Walter J. Stewart, Esq. Board Treasurer Anita W. Coupe, Esq. Wayne Pacelle Neil B. Fang, Esq., C.P.A. President & CEO Judi Friedman G. Thomas Waite III David John Jhirad, Ph.D. Treasurer & CFO Jennifer Leaning, M.D., S.M.H. Roger A. Kindler, Esq. General Counsel & CLO Kathleen M. Linehan, Esq. Janet D. Frake William F. Mancuso Secretary Mary I. Max Andrew N. Rowan, Ph.D. Patrick L. McDonnell Executive Vice President Operations Gil Michaels Michael Markarian Judy Ney Executive Vice President Judy J. Peil External Affairs Marian G. Probst The HSUS by the Numbers . 1 Joshua S. Reichert, Ph.D. Ending Abuse and Suffering: An Epic Battle on Many Fronts . 2 Jeffery O. Rose Uncaging the Victims of Factory Farming: Remarkable Progress for Reforms . 4 James D. Ross, Esq. Taking the Fight to the Courts: Aggressive Litigation Gets Fast Results . 6 Marilyn G. Seyler The Next Time Disaster Strikes: Animals Won’t Be Left Behind . .8 Walter J. Stewart, Esq. The Depravity Worsens: Animal Fighting Takes an Ugly Turn . 10 John E. Taft Animals in Media: Genesis Honors the Best . 12 Andrew Weinstein Drawing a Bead on Blood Sports: Shooting Down Hunters and Tax Cheats . 14 Persia White Last Roundup for Equine Butchers: No More U.S. -

The Art of Talking Back to the Screen with Movie Critic Wesley Morris - November 7, 2014 - Newyork.Com 11/14/16, 4:47 PM

The Art of Talking Back to the Screen with Movie Critic Wesley Morris - November 7, 2014 - NewYork.com 11/14/16, 4:47 PM HOME VISITING NEW YORK LIVING IN NEW YORK Search BROADWAY ▼ HOTELS THINGS TO DO TOURS & ATTRACTIONS EVENTS RESTAURANTS JOBS HOME › JOBS › Everything Jobs › The Art of Talking Back to the Screen with Movie C... REAL ESTATE HOT 5 COOL JOB Q&A The Art of Talking Back to the Screen with READ MORE ABOUT Movie Critic Wesley Morris Pulitzer Prize winner Wesley Morris takes us behind the scenes of his job as a » Broadway » Attractions movie critic » Tours » Restaurants Hotels Real Estate November 7, 2014, Craigh Barboza » » GET WEEKLY 2 Share Like 109 Share Tweet Jobs » NEWS AND One of the most frequent questions people ask Wesley Morris is how can he do his job and still enjoy EXCLUSIVE OFFERS going to the movies. Morris is a Pulitzer Prize-winning movie critic who writes for Grantland, a pop Enter your e-mail address SUBSCRIBE culture and sports website in New York. The perception is that because he is paid to intellectualize his responses to movies, he couldn’t possibly derive any pleasure from them. “They want to know if I turn my brain off,” says Morris, scrunching his eyebrows together. “I’ve never wished that I could turn my brain off while watching a movie.” Movie Critic Wesley Morris What would be the point? The reason Morris is as good a critic as he is (and why people care about what he thinks) is that he sees things others miss, and this knowledge heightens his appreciation of certain aspects of a film.