Soft-Power Triangulation for the Reclamation of a Prodigal Free Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Golden Rules (Bill Maher)

localLEGEND Golden Rules Bill Maher may be one of the nation’s most outspoken cultural critics, but a part of him is still that innocent boy from River Vale. BY PATTI VERBANAS HE RULES FOR LIFE, according to Bill Maher, are unshakable belief in something absurd, it’s amazing how convoluted really quite simple: Treat your fellow man as you wish their minds become, how they will work backward to justify it. We to be treated. Be humane to all species. And, most make the point in the movie: Whenever you confront people about importantly, follow your internal beliefs — not those the story of Jonah and the whale — a man lived in a whale for three thrust upon you by government, religion, or conventional days — they always say, “The Bible didn’t say it was a whale. The thinking. If you question things, you cannot go too far wrong. Bible said it was a big fish.” As if that makes a difference. TMaher, the acerbic yet affable host of HBO’s Real Time, author of New Rules: Polite Musings from a Timid Observer, and a self-described What do you want viewers to take away from this film? “apatheist” (“I don’t know what happens when I die, and I don’t I want them to have a good time. It’s a comedy. Beyond that, I would care”), recently released his first feature film, Religulous, a satirical hope that the people who came into the theater who are already look at the state of world religions. Here he gets real with New Jersey sympathetic to my point of view would realize that there’s millions Life about faith, his idyllic childhood in River Vale, and why the of people like that — who I would call “rationalists” — and they best “new rule” turns out to be an old one. -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Chef Catherine Blake Presented “Cooking for Brain Power”

The Island Vegetarian Vegetarian Society of Hawaii Quarterly Newsletter Inside This Issue Time to Celebrate! VSH Pre-Thanksgiving Dinner 1,3 VSH’s Pre-Thanksgiving Mahalo to Our VSH Volunteers 2 Top Cardiologist Eats Vegan 3 Dinner on Novembef 21 Animal Protein & Osteoporosis 4 Tasty & Meatless at ShareFest 5 Vegan Foodies Club-Sushi Rolls 6-7 Nutrition News 7 If the Oceans Die, We Die 8 Oahu and Maui VSH Events 8,9 Kauai VSH Events 10 Cowspiracy 11 by Karl Seff, PhD Fermentation 12 VSH Board member Heart Healthy Recipe 13 Our Daily Food Choices Matter 14 Upcoming Events 15-18 Membership Benefits 19 Our year-end holidays begin each year with VSH’s annual vegan Pre- Thanksgiving Dinner! This year it will be at McCoy Pavilion at Ala Moana Beach Park, 1201 Ala Moana Boulevard, in Honolulu, and, like last year, it will be on the Friday before Thanksgiving, November 21, 2014. Free Public Lectures As in recent years, Madana Sundari will be preparing a full Thanksgiving vegan buffet for us. Wherever possible, it will be organic and free of GMOs, T. Colin Campbell, PhD hydrogenated oils, MSG, preservatives, and artificial colors and flavors. Open “Nutrition Is Far More Effective to VSH members and non-members, from vegans to non-vegetarians, a record Than Generally Known” high of about 340 people attended last year’s dinner, held at Govinda’s. Tuesday, October 14, 2014 The fare will be very traditional (see the menu on page 3), and entirely home- Ala Wai Golf Course Clubhouse made. Expect a comfortable, quiet Thanksgiving experience. -

Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best

12 | THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES Animals in Media Genesis Honors the Best The HSUS President & CEO Wayne Pacelle, actor James Cromwell, and Joan McIntosh. Genesis Awards founder Gretchen Wyler. he power of the media to project the joy of celebrating animals Wyler came up with the idea for an awards show because she strongly Tand to promote their humane treatment was demonstrated believed that honoring members of the media encourages them to anew at the 20th Anniversary HSUS Genesis Awards staged before spotlight more animal issues, thus increasing public awareness and a glittering audience at California’s Beverly Hilton Hotel in March. compassion. The annual event began as a luncheon with 140 attendees The ceremonies presented awards in 21 print, television, and film and quickly grew into a large gala in Beverly Hills, California, with categories and honored dozens of talented individuals from news more than 1,000 guests. and entertainment media. Beginning with the first ceremony, Genesis Awards entries have The annual celebration recaptured some of the extraordinary events been submitted by the public and by media professionals. Categories that occurred in 2005, from the massive effort to rescue animals span television, film, print, radio, music, and the arts. The awards abandoned in the wake of Hurricane Katrina to such perennial committee chooses winners by secret ballot and the 17 committee concerns as fur, factory farming, and wildlife abuses. It also marked members are selected because of their lengthy personal histories the retirement of HSUS Vice President Gretchen Wyler, who founded in working for the animals. -

Charging Forward for Animals

2006 HSUS Annual Report Celebrating Animals | Confronting Cruelty Charging Forward for Animals R59542.indd C1 5/22/07 14:14:27 Offi cers Directors David O. Wiebers, M.D. Leslie Lee Alexander, Esq. Chair of the Board Patricia Mares Asip Anita W. Coupe, Esq. Peter A. Bender Vice Chair of the Board Barbara S. Brack Walter J. Stewart, Esq. Board Treasurer Anita W. Coupe, Esq. Wayne Pacelle Neil B. Fang, Esq., C.P.A. President & CEO Judi Friedman G. Thomas Waite III David John Jhirad, Ph.D. Treasurer & CFO Jennifer Leaning, M.D., S.M.H. Roger A. Kindler, Esq. General Counsel & CLO Kathleen M. Linehan, Esq. Janet D. Frake William F. Mancuso Secretary Mary I. Max Andrew N. Rowan, Ph.D. Patrick L. McDonnell Executive Vice President Operations Gil Michaels Michael Markarian Judy Ney Executive Vice President Judy J. Peil External Affairs Marian G. Probst The HSUS by the Numbers . 1 Joshua S. Reichert, Ph.D. Ending Abuse and Suffering: An Epic Battle on Many Fronts . 2 Jeffery O. Rose Uncaging the Victims of Factory Farming: Remarkable Progress for Reforms . 4 James D. Ross, Esq. Taking the Fight to the Courts: Aggressive Litigation Gets Fast Results . 6 Marilyn G. Seyler The Next Time Disaster Strikes: Animals Won’t Be Left Behind . .8 Walter J. Stewart, Esq. The Depravity Worsens: Animal Fighting Takes an Ugly Turn . 10 John E. Taft Animals in Media: Genesis Honors the Best . 12 Andrew Weinstein Drawing a Bead on Blood Sports: Shooting Down Hunters and Tax Cheats . 14 Persia White Last Roundup for Equine Butchers: No More U.S. -

1-3 Front CFP 4-6-11.Indd 2 4/6/11 1:22:43 PM

Area/State Colby Free Press Wednesday, April 6, 2011 Page 3 Weather Area races decided Tuesday Legislature votes Corner From “VOTE,” Page 1 Williams has held the seat since Dennis Allison re- signed. R. Alan Jones and Matt Vogler were elected There were no fi led candidates for Brewster City to the council. Dwight Williams was elected to the Council. Bill Selby and Craig Fulwider won with 19 third council seat with fi ve write-in votes. to up speed limit and 8 write-in votes. There were fi ve candidates for four seats on the From “LIMIT,” Page 1 In Gem, Phyllis Ziegelmeier was re-elected as Golden Plains School Board. Vogler got 84 votes; state’s total highway miles. mayor. Warren Ziegelmeier and Annette Spresser Brandi Wark, 97; Jeremy Schiltz, 78; and Paul But Sen. Vicki Schmidt, a were elected to the council. Bruggeman, 98. Joe Broeckelman missed out with the state’s economy. He said Topeka Republican, said the In Rexford, David Williams was elected mayor. 73 votes. companies have an incentive change will make major high- to bypass Kansas in shipping ways more dangerous. products because they can save “I think when the speed lim- time with routes through other it’s 70, people drive 75 or 80. I Clayton man pleads guilty to cruelty states. think when it’s 75, they drive 80 National Weather Service A Clayton man will be spend- on Friday, March 6, the sheriff’s farm, he said, but after consulting “It will make us more com- or 85,” she said. -

Doris Day Ellen Degeneres Kristin Bauer Van Straten Kristen Bell

September 18, 2012 Honorable Edmund G. Brown, Jr. Governor of the State of California State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Senate Bill 1221 (Lieu) Dear Governor Brown, We are writing to ask for your support of an important animal welfare policy that will protect dogs, bears, and bobcats from cruelty. Your enactment of Senate Bill 1221 (Lieu) will bring California in line with other major hunting states around the country that prohibit the inhumane and unsporting use of dogs to chase and kill large mammals. Hound hunting is an unnecessary and cruel practice, opposed by a vast majority of Californians, in which dogs are fitted with high ‐tech radio devices that allow bear and bobcat trophy hunters to follow the pursuit remotely. Dogs are released to chase frightened wild animals often for miles, across all types of habitat, including forests, private property and into national parks. Dogs pursue their target until the exhausted animal climbs a tree to escape or turns to confront the dog pack. The trophy hunter then arrives to the scene and often shoots the animal off a tree branch at point-blank range. Fourteen states—including Colorado, Montana, Oregon, Pennsylvania and Washington—allow bear hunting but prohibit hounding. Montana’s wildlife management officials consider prohibiting bear hounding a feature of the state’s “fair chase” principles. A bear hunting guide in Washington recently noted that fewer mother bears with cubs get shot since hounding has been discontinued. These states have demonstrated that hounding does not serve any wildlife management purpose and is unnecessary. We urge you to sign this important piece of legislation to protect wildlife and dogs. -

Sunday Morning, Oct. 28

SUNDAY MORNING, OCT. 28 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (N) (cc) Your Voice, Your Paid This Week With George Stepha- Paid Paid 2/KATU 2 2 Vote nopoulos (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Paid CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) Face the Nation The NFL Today (N) (Live) (cc) NFL Football Indianapolis Colts at Tennessee Titans. (N) (Live) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise (N) (cc) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 7:00 AM (N) (cc) Meet the Press (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Paid Figure Skating ISU Grand Prix of 8/KGW 8 8 Figure Skating: Skate Canada. (N) Betsy’s Kinder- Angelina Balle- Mister Rogers’ Daniel Tiger’s Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Snowy owls on the North NOVA A 5,000-year-old mummi- 10/KOPB 10 10 garten rina: Next Neighborhood Neighborhood (TVY) (TVY) Europe (TVG) Edge Slope of Alaska. (TVPG) fied corpse. (cc) (TVPG) FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) (Live) (cc) NFL Football Seattle Seahawks at Detroit Lions. (N) (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) (TVPG) Paid Paid Turning Point: Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Life Change Paid Paid Paid Inspiration Today Camp Meeting 22/KPXG 5 5 David Jeremiah (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) Kingdom Con- Turning Point (cc) Praise W/Kenneth Winning Walk (cc) A Miracle For You Redemption (cc) Love Worth Find- In Touch (cc) PowerPoint With It Is Written (cc) Answers With From His Heart 24/KNMT 20 20 nection (TVPG) Hagin (TVG) (cc) ing (TVG) (TVPG) Jack Graham. -

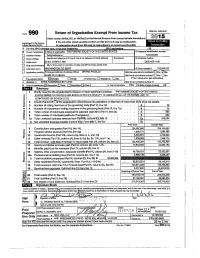

2015-Irs-Form-990.Pdf

Form 990 (2015) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . ✔ 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES’ (THE HSUS) MISSION IS TO CELEBRATE ANIMALS AND CONFRONT CRUELTY. MORE INFORMATION ON THE HSUS’S PROGRAM SERVICE ACCOMPLISHMENTS IS AVAILABLE AT HUMANESOCIETY.ORG. (SEE STATEMENT) 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? . Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization's program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 49,935,884 including grants of $ 5,456,871 ) (Revenue $ 440,435 ) EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT THE WORK OF EDUCATION AND ENGAGEMENT, WITH THE RELATED ACTIVITY OF PUBLIC OUTREACH AND COMMUNICATION TO A RANGE OF AUDIENCES, IS CONDUCTED THROUGH MANY SECTIONS INCLUDING DONOR CARE, COMPANION ANIMALS, WILDLIFE, FARM ANIMALS, COMMUNICATIONS, MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, CONFERENCES AND EVENTS, PUBLICATIONS AND CONTENT, THE HUMANE SOCIETY INSTITUTE FOR SCIENCE AND POLICY, FAITH OUTREACH, RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND OUTREACH, HUMANE SOCIETY ACADEMY, CELEBRITY OUTREACH, AND PUBLIC SERVICE ANNOUNCEMENTS. -

Reviewers' Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher's Religulous

Boise State University ScholarWorks Communication Faculty Publications and Department of Communication Presentations 4-1-2011 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media and Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media and Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 This is an electronic version of an article published in Journal of Media & Religion, Volume 10, Issue 2, 91-112. Journal of Media & Religion is available online at: http://www.informaworld.com. DOI: 10.1080/15348423.2011.572440 Bombing at the Box Office: Reviewers’ Responses to Agnosticism in Bill Maher’s Religulous Rick Clifton Moore Boise State University Abstract This paper examines reviewers’ reactions to Bill Maher’s documentary film Religulous as a way of beginning a discussion of media and religious hegemony. Hegemony theory posits that dominant ideology typically trumps contesting views, even when the latter do manage to leak through the system. Given this, one might expect that film reviewers serve as a second line of defense for entrenched worldviews. Here, however, a thematic analysis of reviews from major national newspapers reveals that critics provided only slight support to traditional religious views Maher challenges in his filmic plea for agnosticism. There is in the world of comedy a plot structure that has traditionally been referred to with the non-inclusive label, “Character gets hoisted with his own petard.” Most of us can envision this element by remembering the classic Warner Brothers Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons. -

I Think That Barack Hussein Obama Should Be Put in Jail

INSIDE THE MIND OF TED NUGENT – RF6 Exclusive Who could be madder than the Motor City Madman? The ‘Nuge got on the famed Royal Flush couch for a therapy session straight to the heart of darkness! He’s tried and he’s true; he’s Ted, white and blue! WHO ARE YOU HATING MOST THESE DAYS, MISTER NUGENT? Pam Anderson. Pam, if you get the dick out of your mouth for 2 minutes, you’re telling me I can’t eat venison? You don’t authorize venison? Here’s the point, this is what I want somewhere in your little interview. My name is Ted Nugent and because of Pam Anderson and because of Bill Maher and because of Paul McCartney, all the members of Peta, whenever I hear the word animal or rights in the same paragraph, I’m killing an extra hundred of something this year. I have unlimited deer tags in Michigan and Texas, and I don’t even need to kill them really, but I’m going to for Bill Maher. I’m not just killing them I’m fucking slaughtering them and I’m going to gut them and skin them, quarter them and butcher them and feed them to the soup kitchen and homeless shelters of America. Not because I need to, because it will cause Bill Maher to shit blood. That’s my goal in life. YOU REALLY DISLIKE BILL MAHER… I’m gonna take off one of my Deep Vibram sole boots and I’m gonna take out my knife and I’m gonna scrape the remains of dead vermin onto his desk and he can find out where his rights start. -

Cover Photo: © Istock.Com/Linas Toleikis 2019

Cover photo: © iStock.com/Linas Toleikis 2019 Dear Friends, It’s obvious when you think about it: All conflict stems from the oppressive structures play in our relations with other animals and idea of “us vs. them.” Our family vs. theirs. Our country vs. theirs. in enabling exploitation and abuse. Our religion vs. theirs. Our species vs. theirs. The victories on the following pages reflect our dynamic campaigns Homo sapiens has ranked itself not just at the top of the list of all to revolutionize the way people think about animals and to challenge species but also in its own category separate from the rest of the the human-supremacist view that we’re superior to other animals © PETA animal kingdom—a ranking that was invented in the 1700s by a in any way that can justify disrespecting, abusing, and slaughtering European biologist who also classified humans into racial subspecies, them. with white people ranked highest. Obviously, the ranking of races was an arbitrary hierarchy based on the one doing the ranking rather We thank all our supporters—especially our Vanguard Society, than on anything rational. In 2019, we launched our “End Speciesism” Augustus Club, and Investigations & Rescue Fund members—for campaign to point out that the same bias is evident in the ranking helping to make this important work possible and for working with of species. us toward animal liberation. We may not fully understand how all beings think—or what they With kind regards, think about—but dismissing their mental world as less deserving of consideration than our own is just vanity.