Florence Shotridge: a Woman, Tlingit, and Museum Educator Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Alaska Boundary Dispute

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

C:\A Projects\AAA IBLA Decs\145IBLA\L014-029.Wpd

HAINES BOROUGH ASSEMBLY, ET AL. IBLA 95-496, etc. 1/ Decided June 30, 1998 Consolidated appeals from a Decision of the Anchorage District Office, Bureau of Land Management, Alaska, approving issuance of commercial special recreation use permits AA-76601 and AA-77475. Affirmed. 1. Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976: Permits--Public Lands: Special Use Permits--Special Use Permits The Bureau of Land Management has discretion under 43 U.S.C. § 1732(b) (1994) and 43 C.F.R. Subpart 8372 to issue special recreation permits for commercial helicopter landings on public lands and to set permit conditions. There must be a compelling reason for modification or reversal of an exercise of this discretionary authority. Mere differences of opinion provide no basis for reversal, and the Board will affirm a decision exercising this authority if the decision is reasonable and supported by the record. 2. Environmental Policy Act--Environmental Quality: Environmental Statements-- National Environmental Policy Act of 1969: Environmental Statements-- National Environmental Policy Act of 1969: Finding of No Significant Impact A BLM finding of no significant impact for a proposed action (allowing landings of helicopters on glaciers on BLM lands) will be affirmed on appeal where BLM took a ____________________________________ 1/ This Decision disposes of the following appeals: Haines Borough Assembly, IBLA 95-496; Lynn Canal Conservation, Inc., IBLA 95-509; City of Skagway, IBLA 95-531; George Figdor, IBLA 95-540; Timothy R. June, IBLA 95-541; Chilkat Indian Village, IBLA 95-542; Fred M. Beeks, IBLA 95-571; Eva J. Beeks, IBLA 95-572; Lani S. -

Routes to Riches 2015 1 Danielhenryalaska.Com

Routes to Riches 2015 1 danielhenryalaska.com Routes to Riches Daniel Lee Henry [email protected] A ground squirrel robe nearly smothered northern Tlingits’ nascent trust in their newly-landed missionaries. Long-time trading ties with Southern Tutchone and Interior Tlingit funneled wealth to Native residents of the upper Lynn Canal. Luxurious furs from the frigid north brought prices many times that of local pelts. For example, while the coastal red fox fur was worth $1.75 in “San Francisco dollars” in 1883, a Yukon silver fox brought up to $50 (about $1200 in 2015). Several times a year, Tlingit expeditions traversed routes considered secret until local leaders revealed their existence to Russians and Americans in the mid-nineteenth century. A day’s paddle to the upper Chilkat River brought travelers to a trail leading over through barrier coastal mountains into the vast, rolling subarctic Interior. On the eastern route, packers left Dyea at the terminus of Taiya Inlet and slogged a twenty-mile trail to a keyhole pass into lake country that drains into the Yukon River headwaters. The image of prospectors struggling up the “Golden Staircase” to Chilkoot Pass engraved the Klondike gold rush of ‘98 onto the license plates of cultural memory. For centuries, Chilkats and Chilkoots sustained a trading cartel connected by their respective routes. From tide’s edge to the banks of the Yukon River four hundred miles north, Tlingits insisted on customer allegiance. They discouraged Interior trading partners from commerce with anyone but themselves and expressly prohibited economic activity without invitation. The 1852 siege of Fort Selkirk and subsequent expulsion of Hudson’s Bay Company demonstrated the market realities of the Chilkat/Chilkoot cartel. -

Juneau Lynn Canal the Fjordland

A spectacular day cruise package through the legendary waters of Lynn Canal! World-Class Tour Boat • Spectacular Scenery Superior Wildlife Viewing and Whale Watching Lynn Canal Juneau Depart Skagway and Haines in the morning and head south Upon arrival in Juneau, board our through Lynn Canal, our motorcoach for a tour of Juneau’s continent’s longest and highlights. See Alaska’s state capitol deepest glacial fjord. building, the governor’s mansion Traveled through the and downtown Juneau. Spend your centuries by trappers afternoon having lunch, shopping and exploring. We provide and traders, gold rush you with a walking tour map to orient you to Juneau’s stampeders, and modern downtown attractions such as Mt. Roberts Tram, Red Dog day adventurers, these Saloon, Alaska State Museum, Juneau-Douglas Museum, waters are rich in both Walter Soboleff Art and Cultural Center human and and St. Nicholas Cathedral. natural history. Sailing in the shadow of Our bus meets the Coast Range, view hanging glaciers you downtown for and historic Eldred Rock lighthouse. a trip to famed Mendenhall Wildlife abounds here; watch bald Glacier before returning to the eagles, harbor seals, porpoise, orcas boat. Savor a hearty bowl of and humpback whales. Stop at a rookery smoked salmon chowder while you where Steller sea lions gather in the summer months to sail north, en route to Skagway and Haines. breed and pup. FJORD EXPRESS TO JUNEAU FROM SKAGWAY OR HAINES DAY CRUISE PACKAGE The Fjordland Adult ................................$169 2017 SCHEDULE A 65-foot, state-of-the-art, fast-hulled catamaran, the MV Child (ages 2-12) .............$139 May 14 – Sept. -

NORTHERN TRANSMISSION LINE of the SOUTHEAST INTERTIE and DOCK ELECTRIFICATION for NORTHERN LYNN CANAL COMMUNITIES-SKAGWAY, HAINES, JUNEAU

NORTHERN TRANSMISSION LINE OF THE SOUTHEAST INTERTIE and DOCK ELECTRIFICATION FOR NORTHERN LYNN CANAL COMMUNITIES-SKAGWAY, HAINES, JUNEAU Description. The Northern Transmission Line (NTL). A high voltage 138 kV and 69 kV transmission line that interconnects Skagway, Haines, and Juneau for Energy Security, Energy Reliability, and Resilience to support sustainable economies of Northern Southeast Alaska. Purpose and Need. The Purpose of the NTL is to create an integrated transmission grid for northern Lynn Canal communities to transfer locally developed electricity between the communities to optimize renewable energy resources, drive down energy costs, open economic opportunities and to create value to the interconnected communities and their industries. Time is Now. Background. Envisioned in 1997, and passed into Public Law in 2000 to create a Southeast Intertie from Ketchikan to Skagway. PL 105-511 authorized $384M for a 25-year plan for interconnecting existing and planned power generation sites with a high voltage electrical intertie serving the communities of the region. The time is now to build the next phase of the SE Intertie to serve northern Lynn Canal communities. The NTL is a fully permitted and construction-ready high voltage transmission line infrastructure to span Skagway, Haines, and Juneau with substations and overhead and submarine transmission segments to serve these communities for the next century. Benefits. • Creates family-wage jobs now to supplement the Alaska economy circulating federal and private infrastructure dollars by building keystone energy infrastructure. • Upgrades and replaces impaired Skagway to Haines undersea transmission cable. • Future proof the Northern Lynn Canal economies and opens up more trade opportunities between communities and with Yukon. -

Unsolved Mystery of the Sinking of the SS Princess Sophia

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 21, 2020 Unsolved Mystery of the Sinking of the SS Princess Sophia The month of October is a reminder of the tragic sinking of the SS Princess Sophia on October 25, 1918 one hundred and two years ago. The Victoria-based ship transported passengers up the coast to Skagway, Alaska stopping at several coastal communities along the way. The shipwreck is the largest marine disaster along the northwest coast of North America and resulted in the unfortunate loss of everyone on board. David Leverton, Executive Director of the Maritime Museum of BC has had an active interest in the marine disaster for many years and has co-authored a book with Judy Thompson that looks at the shipwreck and the background of the known passengers and crew who were onboard at the time of the sinking.i Mr. Leverton stated that, "the 100th Anniversary commemorating this event helped to increase public awareness about the story and we still continue to learn more about the mystery of what happened including the story surrounding the fate of the lone dog that was known to have survived the disaster." 634 HUMBOLDT ST., VICTORIA, BC, V8W 1A4 | 250-385-4222 | mmbc.bc.ca Several months after the tragic sinking, The Alaska Daily Empire on Thursday, March 6, 1919, reported that a small dog had been found two days after the shipwreck covered in oil in Tee Harbor which is about 20 miles away and that it had been living at the nearby Auk Bay Cannery. On March 14, 1919, The Alaska Daily Empire reported that the dog had been positively identified as a thoroughbred English Setter belonging to Captain James Alexander and his wife Louisa. -

Bookletchart™ Lynn Canal – Point Sherman to Skagway NOAA Chart 17317

BookletChart™ Lynn Canal – Point Sherman to Skagway NOAA Chart 17317 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the Eldred Rock, about 7.3 miles NNW from Point Sherman and 1.4 miles from the E shore of Lynn Canal, is marked by Eldred Rock Light National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (58°58'15"N., 135°13'15"W.), 91 feet above the water, shown from a National Ocean Service white octagonal tower on a building. The white buildings on the rock are Office of Coast Survey also prominent. A ledge extends about 300 yards NW from Eldred Rock, and a rock with ¾ fathom over it is 0.3 mile 325° from Eldred Rock Light. www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov A submerged wreck is about 150 yards SE of the ¾-fathom sounding. 888-990-NOAA Haines is a city with several hotels, motels, machine shops, and general stores on the W side of Portage Cove. It is 950 miles from Seattle and 88 What are Nautical Charts? miles from Juneau, and is at the S end of a highway running along the Chilkat River and Klehini River through the Porcupine Mining District and Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show connecting with the Alaska Highway. water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Pilotage, Haines.–Pilotage, except for certain exempted vessels, is more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and compulsory for all vessels navigating the inside waters of the State of efficient navigation. -

A History of Changing Ideas

NATIVE ART OF THE NORTHWEST COAST A HISTORY OF CHANGING IDEAS Edited by Charlotte Townsend-Gault, Jennifer Kramer, and Ḳi-ḳe-in ubc press vancouver toronto Sample Material © 2013 UBC Press Contents Contents with Excerpts Listed ix List of Figures xxix Preface xxxiii Introduction: The Idea of Northwest Coast Native Art 1 Charlotte Townsend-Gault, Jennifer Kramer, and Ḳi-ke-iṇ 1 Interpreting Cultural Symbols of the People from the Shore 15 Daisy Sewid-Smith 2 Hilth Hiitinkis – From the Beach 26 Ḳi-ke-iṇ 3 Haida Cosmic 31 Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas 4 From Explorers to Ethnographers, 1770-1870 46 Ira Jacknis 5 Thresholds of Meaning: Voice, Time, and Epistemology in 92 the Archaeological Consideration of Northwest Coast Art Andrew Martindale 6 Objects and Knowledge: Early Accounts from Ethnographers, and 128 Their Written Records and Collecting Practices, ca. 1880-1930 Andrea Laforet 7 “That Which Was Most Important”: Louis Shotridge on Crest Art 166 and Clan History Judith Berman 8 Anthropology of Art: Shifting Paradigms and Practices, 1870s-1950 203 Bruce Granville Miller Sample Material © 2013 UBC Press vi contents 9 Going by the Book: Missionary Perspectives 234 John Barker 10 The Dark Years 265 Gloria Cranmer Webster 11 Surrealists and the New York Avant-Garde, 1920-60 270 Marie Mauzé 12 Northwest Coast Art and Canadian National Identity, 1900-50 304 Leslie Dawn 13 Art/Craft in the Early Twentieth Century 348 Scott Watson 14 Welfare Politics, Late Salvage, and Indigenous (In)Visiblity, 1930-60 379 Ronald W. Hawker 15 Form First, Function -

DRAFT—Report to the Alaska Board of Fisheries

DRAFT—Report to the Alaska Board of Fisheries Chilkat River and King Salmon River King Salmon Stock Status and Action Plan, 2018. By Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Staff, Southeast Alaska Region January 2018 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Divisions of Sport Fish and Commercial Fisheries Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used without definition in the following reports by the Divisions of Sport Fish and of Commercial Fisheries: Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, Special Publications and the Division of Commercial Fisheries Regional Reports. All others, including deviations from definitions listed below, are noted in the text at first mention, as well as in the titles or footnotes of tables, and in figure or figure captions. Weights and measures (metric) General Measures (fisheries) centimeter cm Alaska Administrative fork length FL deciliter dL Code AAC mideye-to-fork MEF gram g all commonly accepted mideye-to-tail-fork METF hectare ha abbreviations e.g., Mr., Mrs., standard length SL kilogram kg AM, PM, etc. total length TL kilometer km all commonly accepted liter L professional titles e.g., Dr., Ph.D., Mathematics, statistics meter m R.N., etc. all standard mathematical milliliter mL at @ signs, symbols and millimeter mm compass directions: abbreviations east E alternate hypothesis HA Weights and measures (English) north N base of natural logarithm e cubic feet per second ft3/s south S catch per unit effort CPUE foot ft west W coefficient of variation CV gallon gal copyright common test statistics (F, t, χ2, etc.) inch in corporate suffixes: confidence interval CI mile mi Company Co. -

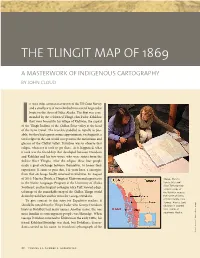

The Tlingit Map of 1869

The TlingiT Map of 1869 A MAsterwork of IndIgenous CArtogrAphy By John Cloud n july 1869, george davidson of the US Coast Survey and a small party of men climbed into several large cedar boats on the shore of Sitka, Alaska. The fleet was com- manded by the celebrated Tlingit clan leader Kohklux; they were bound for his village of Klukwan, the capital of the Tlingit Indians of the Chilkat River valley at the head Iof the Lynn Canal. The travelers paddled as rapidly as pos- sible, for they had a great cosmic appointment: on August 8, a total eclipse of the sun would sweep across the mountains and glaciers of the Chilkat valley. Davidson was to observe that eclipse, whatever it took to get there. As it happened, what it took was the friendship that developed between Davidson and Kohklux and his two wives, who were sisters from the Stikine River Tlingits. After the eclipse, these four people made a great exchange between themselves, to honor their experience. It came to pass that, 141 years later, a surrogate from that exchange finally returned to Klukwan. In August of 2010, Marsha Hotch, a Tlingit of Klukwan and a professor Above, Marsha in the Native Languages Program at the University of Alaska Hotch (left) and Southeast, and her linguist colleague Alice Taff, viewed a digi- Alice Taff examine a replica copy of tal image of the remarkable map of the Chilkat Tlingit world the Kohklux map at drawn by Kohklux and his wives for George Davidson. the home of Kathy To give context to this story for Expedition readers, it and Bill Ruddy, near Juneau, Alaska. -

Southeast Alaska Voluntary Waterway Guide

SOUTHEAST ALASKA VOLUNTARY WATERWAY GUIDE Revisions Established: June 8, 1996 Revised: April 29, 1997 Revised: January 29, 1998 Revised: January 27, 1999 Revised: March 1, 2000 Revised: April, 14, 2001 Revised: February 2002 Revised: April 2003 Revised: April 2004 Revised: April 2005 Revised: January 2006 Revised: March 2007 Revised Cover photo of the Dawn Princess in Tracy Arm taken by Capt. Doug Hanson, SEAPA. Cover designed by Candy Peterson, SEAPA & Rainforest Web Design. The Southeast Alaska Voluntary Waterway Guide (VWG or Guide) was developed by the Marine Safety Task Force (MSTF or Task Force) and is intended for use by deep-draft vessels, primarily cruise vessels which are subject to pilotage. The VWG is published by the Southeast Alaska Pilots Association and is distributed by Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska and the United States Coast Guard. The MSTF includes representatives from: • The United States Coast Guard • The North West Cruise Ship Association • Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska • The Southeast Alaska Pilots’ Association Mariners should be aware that the Marine Safety Task Force has additional guidance for deep draft vessels operating in Southeast Alaska. The most recent version can be found at http://www.seapa.com/waterway/waterway_guide.pdf. For more information contact Southeast Alaska Pilots’ Association ▪ 1621 Tongass Avenue, Suite 300 Ketchikan, Alaska 99901 ▪ Ph. 907-225-9696 ▪ Fax 907-247-9696 email: [email protected] ▪ www.seapa.com Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska P.O. Box 8080 ▪ Ketchikan, Alaska 99901 Ph. 907-225-0999 North West Cruise Ship Association 100-1111 West Hastings Street ▪ Vancouver, BC, V6E 2J3 U.S. -

RESOUND a QUARTERLY of the Archives of Traditional Music Volume IX, Number 1 January 1990

RESOUND A QUARTERLY OF THE Archives of Traditional Music Volume IX, Number 1 January 1990 Program From the Director Technology in the Past and in the Present Wednesday, March 21 5:00-8:00 p.m. Registration Ruth M. Stone 8:00 p.m. Opening and Reception Thursday, March 22 On January I, all of the field collections and some 9:00 a.m.-12:30 p.m. commerical recordings held by the Archives of Traditional Session 1: Historical Views on Early Recording Music became a part of the new computerized system of Discussants: Nancy Schmidt and Phyllis Martin, Indiana access to library materials at Indiana University. A University number of computer terminals are now in the Listening Erika Brady, Western Kentucky University, "Looking for Library for patrons to search for materials throughout the the Band: Early Patterns of Response to the University library system, using keyword Boolean Phonograph" strategies as well as more conventional approaches. Philip V. Bohlman and Carolyn S. Johnson, University of Furthermore, if any patron at the Archives or at any of Chicago, "Recording the World's Music in 1893: the I. U. libraries searches for the works of a particular Recreating the Field at Chicago's Columbian individual in the database, she or he will be presented Exposition" with the listings of both printed and recorded materials. Douglas R. Parks, Indiana University, "The Roaming Only a week after the system was operating, a visitor Scout Cylinder Recordings as a Source of Pawnee from Germany who was working in the main library Ethnography" appeared with a list of tapes she wanted to hear which Michael Heisley, Southwest Museum, Los Angeles, she had found through the computer search.