A Stable Environment: Surrogacy and the Good Life in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open PDF 181KB

Constitution Committee Corrected oral evidence: Future governance of the UK Tuesday 13 July 2021 2.15 pm Watch the meeting Members present: Baroness Taylor of Bolton (The Chair); Baroness Corston; Baroness Doocey; Baroness Drake; Lord Dunlop; Lord Faulks; Baroness Fookes; Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield; Lord Hope of Craighead; Lord Howarth of Newport; Lord Howell of Guildford; Lord Sherbourne of Didsbury; Baroness Suttie. Evidence Session No. 6 Virtual Proceeding Questions 69 - 80 Witness I: Rt Hon Angus Robertson MSP, Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, Scottish Government. USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken in public and webcast on www.parliamentlive.tv. 1 Examination of witness Angus Robertson. Q69 The Chair: This is the Constitution Committee of the House of Lords. We are conducting an inquiry into the future governance of the United Kingdom, and our witness this afternoon is the right honourable Angus Robertson, who is Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture in the Scottish Government. Good afternoon to you, Angus Robertson. Angus Robertson: Good afternoon. Thanks for inviting me. The Chair: You are very welcome. Can we start our discussion with a general question? What is the current state of the union from your point of view, from your Government’s point of view? Given all that is being said at the moment, this is a very topical question and very fundamental to the work that we are doing. Angus Robertson: Of course. In a nutshell, I would probably say that the current state of the union is unfit for purpose. -

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER As Of: 01 October 2020

ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER as of: 01 October 2020 Closing Order Property Reference:Address of Property: Date Served: Demolished, Revoked or Withdrawn 72/00014/RES73 Main Street Newmill Keith Moray AB55 6TS 04 August 1972 77/00012/RES3 Great Western Road Buckie Moray AB56 1XX 26 June 1977 76/00001/RESNetherton Farm Cottage Forres Moray IV36 3TN 07 November 1977 81/00008/RES12 Seatown Lossiemouth Moray IV31 6JJ 09 December 1981 80/00007/RESBroadrashes Newmill Keith Moray AB55 6XE 29 November 1989 89/00003/RES89 Regent Street Keith Moray AB55 5ED 29 November 1989 93/00001/RES4 The Square Archiestown Aberlour Moray AB38 7QX 05 October 1993 94/00006/RESGreshop Cottage Forres Moray IV36 2SN 13 July 1994 94/00005/RESHalf Acre Kinloss Forres Moray IV36 2UD 24 August 1994 20/00005/RES2 Pretoria Cottage Balloch Road Keith Moray 30 May 1995 95/00001/RESCraigellachie 4 Burdshaugh Forres Moray IV36 1NQ 31 October 1995 78/00008/RESSwiss Cottage Fochabers Moray IV32 7PG 12 September 1996 99/00003/RES6 Victoria Street Craigellachie Aberlour Moray AB38 9SR 08 November 1999 01 October 2020 Page 1 of 14 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH - HOUSING ORDERS PUBLIC REGISTER as of: 01 October 2020 Closing Order Property Reference:Address of Property: Date Served: Demolished, Revoked or Withdrawn 01/00001/RESPittyvaich Farmhouse Dufftown Keith Moray AB55 4BR 07 November 2001 03/00004/RES113B Mid Street Keith Moray AB55 5AE 01 April 2003 05/00001/RESFirst Floor Flat 184 High Street Elgin Moray IV30 1BA 18 May 2005 03 September 2019 05/00002/RESSecond -

KD Report Kinloss

Braves and Apaches take Kinloss by storm!! What a way for our 2018 Bader Braves Young Aviators programme to kick off!! Glorious weather, Braves, Apaches, ideal flying conditions, fire engines and loads of fun!!!! It has become the custom to start our Young Aviators season with The Moray Flying Club at their Kinloss Barracks home (formerly RAF Kinloss) on the bank of the beautiful Moray Firth in the North of Scotland. This year was no exception but the weather was in that right from dawn the sky was blue and the sun shone and there were absolutely no concerns about getting all the flights in during the day. Once again our good friend and chief whipper-in, George Mackenzie, had all the Braves, their families and a good number of volunteers lined up at the main guardroom at 08.30 ready for the security formalities to be completed before the substantial convoy snaked its way around the perimeter road on its 1.5 mile journey to the Clubhouse, our home for the day. Club members were waiting to welcome their guests with the usual teas, coffees and rather scrummy biscuits and made sure everyone was comfortable before introductions, briefings and explanations. The first wave of flights were scheduled for 09.15 so there was no time to waste before the first three Young Aviators were filling in authority documents whilst pilots completed flying logs and Operations Chief, Mick Dye, ushered everyone along ensuring that things flowed smoothly. The three club Cessna Aircraft were impressively lined up awaiting their first passengers who were quickly each aircraft taxied out to the far end of the runway, a journey of some distance and probably equivalent of something like two quid single on a London bus, before lining up ready for take-off. -

Community Safety Partnership Report Issue 2022 September 2018

Community Safety Partnership Report Issue 2022 September 2018 Community Safety Community Safety is about protecting people’s rights to live in confidence without fear for their own or other people’s safety ensuring that people are safe from crime, disorder and danger and free from injury and harm and communities are socially cohesive and tolerant; are resilient and able to support individuals to take responsibility for their wellbeing The Community Safety Partnership aims to improve community safety across Moray by identifying and addressing immediate concerns in order to protect the most vulnerable and at risk and be proactive to ensure that communities feel safe. The CSP comprises of various Moray Council services, Police Scotland, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, NHS Grampian, tsiMORAY and Registered Social Landlords. WATER SAFETY With the continuing warm weather it is always tempting to go swimming to cool off. Water may look safe, but it can be dangerous. Learn to spot and keep away from dangers. You may swim well in a warm indoor pool, but that does not mean that you will be able to swim in cold water. The dangers of water include: • it is very cold • there may be hidden currents • it can be difficult to get out (steep slimy banks) • it can be deep • there may be hidden rubbish, e.g. shopping trolleys, broken glass • there are no lifeguards • it is difficult to estimate depth • it may be polluted and may make you ill Moray Local Command Area - Community Policing Inspectors Elgin Wards - Inspector Graeme Allan [email protected] -

SAUCHENBUSH ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY View SAUCHENBUSH, ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY, AB38 7AG

SAUCHENBUSH ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY View SAUCHENBUSH, ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY, AB38 7AG An impressive renovated farmhouse in a stunning elevated position Rothes 2 miles; Aberlour 6.5 miles; Elgin 10 miles. About 10.3 acres (4.17 ha). Ground Floor: Vestibule. Utility Room. Shower Room. Breakfasting Kitchen/Family Room. Hall. Sitting Room. Sun Room. Dining Room. Study. First Floor: Landing. 5 Bedrooms (2 En Suite). Family Bathroom. • Spacious family home • Some works outstanding • 6 superb stables and 1 tack room • Excellent paddock and former sand based riding arena • Stunning views over the surrounding countryside 5 Commerce Street Elgin Moray IV30 1BS 01343 546362 [email protected] to stay, eat and shop. The county is famed tow storeys. On the ground floor, the back for its breathtaking scenery, long sandy door opens into a spacious utility area beaches and wildlife and offers wonderful with a sink, wall and floor units, space leisure and recreational opportunities. for white goods and a shower room. A There are many golf courses accessible door leads to the kitchen/dining/family within a short drive including the room which is generous in size with attractive course in Rothes and as a plenty of work surface space and quality popular tourist area, local attractions fittings. The hall provides access to include ‘The Whisky Trail’, ‘The Speyside the wonderfully light triple aspect sun Way’ which passes nearby, Cairngorm room which enjoys stunning views over National Park, together with many ancient Strathspey and the Glen of Rothes. It also monuments, castles, buildings and has a door out to the garden. -

Scottish Birds

SCOTTISH BIRDS THE JOURNAL OF THE SCOTTISH ORNITHOLOGISTS' CLUB Volume 7 No. 7 AUTUMN 1973 Price SOp SCOTTISH BIRD REPORT 1972 1974 SPECIAL INTEREST TOURS by PEREGRINE HOLIDAYS Directors : Ray Hodgkins, MA. (Oxon) MTAI and Patricia Hodgkins, MTAI. Each tour has been surveyed by one or both of the directors and / or chief guest lecturer; each tour is accompanied by an experienced tour manager (usually one of the directors) in addition to the guest lecturers. All Tours by Scheduled Air Services of International Air Transport Association Airlines such as British Airways, Olympic Airways and Air India. INDIA & NEPAL-Birds and Large Mammals-Sat. 16 February. 20 days. £460.00. A comprehensive tour of the Game Parks (and Monuments) planned after visits by John Gooders and Patricia and Ray Hodgkins. Includes a three-night stay at the outstandingly attractive Tiger Tops Jungle Lodge and National Park where there is as good a chance as any of seeing tigers in the really natural state. Birds & Animals--John Gooders B.Sc., Photography -Su Gooders, Administration-Patricia Hodgkins, MTAI. MAINLAND GREECE & PELOPONNESE-Sites & Flowers-15 days. £175.00. Now known as Dr Pinsent's tour this exhilarating interpretation of Ancient History by our own enthusiastic eponymous D. Phil is in its third successful year. Accompanied in 1974 by the charming young lady botanist who was on the 1973 tour it should both in experience and content be a vintage tour. Wed. 3 April. Sites & Museums-Dr John Pinsent, Flowers-Miss Gaye Dawson. CRETE-Bird and Flower Tours-15 days. £175.00. The Bird and Flower Tours of Crete have steadily increased in popularity since their inception in 1970 with the late Or David Lack, F.R.S. -

Littlehaugh Cottage, Glen of Rothes, Aberlour, Moray

LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY LITTLEHAUGH COTTAGE, GLEN OF ROTHES, ABERLOUR, MORAY Two cottages built in the 1927 converted into one spacious home situated between Elgin and the village of Rothes. Description A96(T) road enabling Inverness and Aberdeen Airports General Information Littlehaugh Cottage is a charming 4 bedroom single to be reached within one and 1¼ hours respectively storey dwelling with slate roof. The property is traffic permitting. There are railway stations at Elgin, Services surrounded by a good sized garden and grounds of Aviemore (30 minutes), Inverness and Aberdeen. Mains water and electricity, private drainage and oil fired about 0.30 Ha (0.74 acres) and has good views to the central heating. east. It benefits from pvc double glazing and oil fired The Spey Valley is renowned for its excellent salmon central heating. fishing on the River Spey with the Rothes, Delfur and Rights of Way, Easements & Wayleaves Arndilly beats all within close proximity. The area also The access between the public road and the cottage is Situation abounds with golf courses and sandy beaches along included in the sale as shown on the plan. The small town of Rothes about 1½ miles to the the Moray coast. There are other opportunities for south provides basic daily requirements including two leisure activities such as mountaineering, skiing and Local Authority convenience stores, a butcher, chemist, library, post mountain biking in the nearby Cairngorm National Park. office, hotels and medical centre. Aberlour, about The Moray Council, Council Office 5 miles to the south has a supermarket, banks, a good Accommodation High Street, Elgin, Moray IV30 1BX range of shops, leisure facilities, doctor’s surgery and Littlehaugh Cottage is situated adjacent to the A941 Tel: 01343 543451 www.moray.gov.uk Speyside High School. -

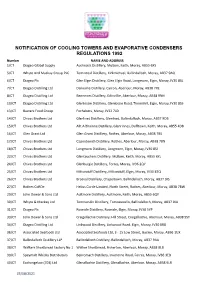

Cooling Tower Register

NOTIFICATION OF COOLING TOWERS AND EVAPORATIVE CONDENSERS REGULATIONS 1992 Number NAME AND ADDRESS 1/CTDiageo Global Supply Auchroisk Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6XS 5/CTWhyte And Mackay Group PLC Tomintoul Distillery, Kirkmichael, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9AQ 6/CTDiageo Plc Glen Elgin Distillery, Glen Elgin Road, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SL 7/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Dailuaine Distillery, Carron, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7RE 8/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Benrinnes Distillery, Edinvillie, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 9NN 10/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Glenlossie Distillery, Glenlossie Road, Thomshill, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SS 13/CTBaxters Food Group Fochabers, Moray, IV32 7LD 14/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenlivet Distillery, Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9DB 15/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Allt A Bhainne Distillery, Glenrinnes, Dufftown, Keith, Moray, AB55 4DB 16/CTGlen Grant Ltd Glen Grant Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BS 17/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Caperdonich Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BN 18/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Longmorn Distillery, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SJ 22/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glentauchers Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6YL 24/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenburgie Distillery, Forres, Moray, IV36 2QY 25/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Miltonduff Distillery, Miltonduff, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8TQ 26/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Braeval Distillery, Chapeltown, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9JS 27/CTRothes CoRDe Helius Corde Limited, North Street, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BW 29/CTJohn Dewar & Sons Ltd Aultmore Distillery, -

Of 5 Polling District Polling District Name Polling Place Polling Place Local Government Ward Scottish Parliamentary Cons

Polling Polling District Local Government Scottish Parliamentary Polling Place Polling Place District Name Ward Constituency Houldsworth Institute, MM0101 Dallas Houldsworth Institute 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Dallas, Forres, IV36 2SA Grant Community Centre, MM0102 Rothes Grant Community Centre 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray 46 - 48 New Street, Rothes, AB38 7BJ Boharm Village Hall, MM0103 Boharm Boharm Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Mulben, Keith, AB56 6YH Margach Hall, MM0104 Knockando Margach Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Knockando, Aberlour, AB38 7RX Archiestown Hall, MM0105 Archiestown Archiestown Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray The Square, Archiestown, AB38 7QX Craigellachie Village Hall, MM0106 Craigellachie Craigellachie Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray John Street, Craigellachie, AB38 9SW Drummuir Village Hall, MM0107 Drummuir Drummuir Village Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Drummuir, Keith, AB55 5JE Fleming Hall, MM0108 Aberlour Fleming Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Queens Road, Aberlour, AB38 9PR Mortlach Memorial Hall, MM0109 Dufftown & Cabrach Mortlach Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Albert Place, Dufftown, AB55 4AY Glenlivet Public Hall, MM0110 Glenlivet Glenlivet Public Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EJ Richmond Memorial Hall, MM0111 Tomintoul Richmond Memorial Hall 1 - Speyside Glenlivet Moray Tomnabat Lane, Tomintoul, Ballindalloch, AB37 9EZ McBoyle Hall, BM0201 Portknockie McBoyle Hall 2 - Keith and Cullen Banffshire and Buchan Coast Seafield -

Ronnie's Cabs

transport guide FOREWORD The Moray Forum is a constituted voluntary organisation that was established to provide a direct link between the Area Forums and the Moray Community Planning Partnership. The Forum is made up of two representatives of each of the Area Forums and meets on a regular basis. Further information about The Moray Forum is available on: www.yourmoray.org.uk Area Forums are recognised by the Moray Community Planning Partnership as an important means of engaging local people in the Community Planning process. In rural areas - such as Moray - transport is a major consideration, so in September 2011 the Moray Forum held its first transport seminar to look at the issues and concerns that affect our local communities in respect of access to transport. Two actions that came from that event was the establishment of a Passenger Forum and a Transport Providers Network. This work was taken forward by the Moray Forum Transport Working Group made up of representatives of the Area Forums, Moray Council, NHS Grampian, tsiMORAY, and community transport schemes. In September 2013 the Working Group repeated the seminar to see how much progress had been made on the actions and issues identified in 2011. As a direct result of the work of the Group this Directory has been produced in order to address an on-going concern that has been expressed of the lack of information on what transport is available in Moray, the criteria for accessing certain transport services, and where to go for further advice. The Moray Forum Transport Working Group would like to acknowledge the help of all the people who provided information for this Directory, and thereby made a contribution towards the integration of public, private and community transport services within Moray. -

Black's Morayshire Directory, Including the Upper District of Banffshire

tfaU. 2*2. i m HE MOR CTORY. * i e^ % / X BLACKS MORAYSHIRE DIRECTORY, INCLUDING THE UPPER DISTRICTOF BANFFSHIRE. 1863^ ELGIN : PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY JAMES BLACK, ELGIN COURANT OFFICE. SOLD BY THE AGENTS FOR THE COURANT; AND BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. : ELGIN PRINTED AT THE COURANT OFFICE, PREFACE, Thu ''Morayshire Directory" is issued in the hope that it will be found satisfactorily comprehensive and reliably accurate, The greatest possible care has been taken in verifying every particular contained in it ; but, where names and details are so numerous, absolute accuracy is almost impossible. A few changes have taken place since the first sheets were printed, but, so far as is known, they are unimportant, It is believed the Directory now issued may be fully depended upon as a Book of Reference, and a Guide for the County of Moray and the Upper District of Banffshire, Giving names and information for each town arid parish so fully, which has never before been attempted in a Directory for any County in the JTorth of Scotland, has enlarged the present work to a size far beyond anticipation, and has involved much expense, labour, and loss of time. It is hoped, however, that the completeness and accuracy of the Book, on which its value depends, will explain and atone for a little delay in its appearance. It has become so large that it could not be sold at the figure first mentioned without loss of money to a large extent, The price has therefore been fixed at Two and Sixpence, in order, if possible, to cover outlays, Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/blacksmorayshire1863dire INDEX. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................