Brexit and the Future of the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open PDF 181KB

Constitution Committee Corrected oral evidence: Future governance of the UK Tuesday 13 July 2021 2.15 pm Watch the meeting Members present: Baroness Taylor of Bolton (The Chair); Baroness Corston; Baroness Doocey; Baroness Drake; Lord Dunlop; Lord Faulks; Baroness Fookes; Lord Hennessy of Nympsfield; Lord Hope of Craighead; Lord Howarth of Newport; Lord Howell of Guildford; Lord Sherbourne of Didsbury; Baroness Suttie. Evidence Session No. 6 Virtual Proceeding Questions 69 - 80 Witness I: Rt Hon Angus Robertson MSP, Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture, Scottish Government. USE OF THE TRANSCRIPT This is a corrected transcript of evidence taken in public and webcast on www.parliamentlive.tv. 1 Examination of witness Angus Robertson. Q69 The Chair: This is the Constitution Committee of the House of Lords. We are conducting an inquiry into the future governance of the United Kingdom, and our witness this afternoon is the right honourable Angus Robertson, who is Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, External Affairs and Culture in the Scottish Government. Good afternoon to you, Angus Robertson. Angus Robertson: Good afternoon. Thanks for inviting me. The Chair: You are very welcome. Can we start our discussion with a general question? What is the current state of the union from your point of view, from your Government’s point of view? Given all that is being said at the moment, this is a very topical question and very fundamental to the work that we are doing. Angus Robertson: Of course. In a nutshell, I would probably say that the current state of the union is unfit for purpose. -

Bute House the Offi Cial Residence of the First Minister of Scotland

Bute House The offi cial residence of the First Minister of Scotland Bute House 20pp brochure 02.indd 1 17/07/2017 08:53 Welcome to Bute House ince I became First Minister, I have welcomed thousands of people to Bute House. As the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland, it is here that I host official guests from this country and overseas on behalf of the nation. Bute House is also the meeting place of the Scottish Cabinet and the venue for official functions including meetings, receptions, lunches and dinners. Within these walls, I get to bring together people from all walks of life through meetings with business leaders, public service employees and the voluntary sector, and receptions to celebrate all aspects of Scottish society and success. Every Christmas, I even get to welcome youngsters from around the country for an annual children’s party. All year round Bute House performs a dual role of both residence and place of work for the First Minister. All four of my predecessors lived here too, and their portraits line the wall of the staircase leading to the Cabinet Room. Before the Scottish Parliament was reconvened in 1999, Bute House was home to eight different Secretaries of State for Scotland from 1970 onwards. Many of the key conversations and decisions in recent Scottish political history have taken place within these walls. Even without its modern role, however, Bute House would be of significant historic interest. It was built in the late 18th century, and is at the heart of one of the great masterpieces of Georgian architecture – the north side of Robert Adam’s Charlotte Square. -

1 Andrew Marr Show, Nicola Sturgeon, First Minister of Scotland, 24Th January, 2021

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, NICOLA STURGEON, FIRST MINISTER OF SCOTLAND, 24TH JANUARY, 2021 ANDREW MARR SHOW, 24TH JANUARY, 2021 NICOLA STURGEON MSP First Minister of Scotland and Leader of the SNP (Please check against delivery (uncorrected copies)) AM: The death rate in Scotland is now below England but the vaccine roll out has been slower. Why? I’m joined now from Glasgow by the First Minister of Scotland and SNP Leader, Nicola Sturgeon. Nicola Sturgeon, there will be lots of people at home in Scotland in their 80s watching this interview still waiting for their vaccine appointment and reading that down south in England more than 50% of 80 year olds have been vaccinated already. What would you say to them? NS: We took a deliberate decision in line with JCVI advice to focus initially on vaccinating older residents in care homes because that is going to have the most immediate and biggest impact on reducing the death toll. You’ve quizzed me rightly the last couple of times I’ve been on the programme about the death toll in our care homes, so I heard Matt Hancock on the programme earlier say that about three quarters of care home residents in England have been vaccinated in Scotland. That figure right now is 95% of care home residents. It takes longer, it’s more resource intensive to do care homes but it’s the right decision in my view. Of course we’re now rapidly catching up on the over 80s in the community. We’ve done around 40% of those and that’s gathering pace every single day. -

SNP Manifesto 2016

RE-ELECT Manifesto 2016 SCOTTISH NATIONAL PARTY Since 2007 every home in Scotland has benefited in Our aim has always been to build a country where strong some way from SNP government policies. public services are underpinned by a successful economy. Yes, we are proud of our record, but we know there is We have transformed education, bolstered our health still much more to do. service, reformed policing, taken employment levels to a record high and built thousands of affordable homes. With your support we can build on the achievements of the past nine years. Our investment ha s delivered modern learning environments in our schools, colleges and universities, as well a s some Together, we can continue to shape a better future for of the bigges t transport improvements the country Scotland for everybody who lives and works here. has ever seen. 2 MANIFESTO 2016 DOWNLOAD SNP VISION APP The app enables you to watch additional manifesto content on your mobile or tablet device. Open the app, then simply point your camera at one of our scannable icons or images. Available on Apple iOS and Android. MARVEL ON THE FORTH The £1.4 billion Queensferry Crossing is on time and on budget. SCOTTISH NATIONAL PARTY STRONGER FOR SCOTLAND Standing up for Scotland is what we do. We never shy away from an opportunity to make this country even stronger. The SNP government stepped in to save Scottish steel, Prestwick Airport, and the Ferguson shipyard. And when the Tories tried to cut Scotland’s budget by £7 billion, we saw them off. -

The Executive's International Relations and Comparisons with Scotland & Wales

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 04/21 27/11/2020 NIAR 261-20 The Executive’s International Relations and comparisons with Scotland & Wales Stephen Orme Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 261-20 Briefing Paper Key Points This briefing provides information on the Northern Ireland Executive’s international relations strategy and places this in a comparative context, in which the approaches of the Scottish and Welsh governments are also detailed. The following key points specify areas which may be of particular interest to the Committee for the Executive Office. The Executive’s most recent international relations strategy was published in 2014. Since then there have been significant changes in the global environment and Northern Ireland’s position in it, including Brexit and its consequences. Northern Ireland will have a unique and ongoing close relationship with the EU, due in part to the requirements of the Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol. The Scottish and Welsh parliaments have launched and/or completed inquiries into their countries’ international relations in recent years. The Scottish and Welsh governments have also taken recent steps to update and refresh their approach to international relations. There is substantial variation in the functions of the international offices of the devolved administrations. NI Executive and Scottish Government offices pursue a broad range of diplomatic, economic, cultural, educational and specific policy priorities, with substantial variation between offices. Welsh Government offices, meanwhile, appear primarily focused on trade missions. It is therefore difficult to compare the international offices of the three administrations on a “like for like” basis. -

Coronavirus Timeline: Welsh and UK Government’S Response Research Briefing

Welsh Parliament Senedd Research Coronavirus timeline: Welsh and UK Government’s response Research Briefing The table below highlights key developments in Wales and the UK in response to coronavirus (Covid-19). Senedd elections are held 6 May 2021 The people of Wales head to the polls to vote for the next Senedd / Welsh Parliament. Wales moves into alert level 3 3 May 2021 From today the whole of Wales is under alert level 3 restrictions, as confirmed by the First Minister on 30 April. The next review of the coronavirus restrictions is due by 13 May 2021 so will be carried out by the new Welsh Government following the Senedd election on 6 May 2021. The current Welsh Government previously indicated that Wales could move into alert level 2 on 17 May 2021. Senedd election to go ahead on 6 May 2021 27 April 2021 Th Welsh Elections (Coronavirus) Act 2021 requires the Welsh Ministers to review the holding of the 2021 Senedd election due to coronavirus. Following the fourth and final review, it was not deemed necessary to postpone the election. Review of the coronavirus regulations www.senedd.wales/research Coronavirus timeline: Welsh and UK Government’s response 23 April 2021 Following the required review of the coronavirus restriction regulations, the First Minister announces that from 26 April outdoor swimming pools, outdoor attractions, organised outdoor activities for up to 30 people and wedding receptions for up to 30 people can take place along with the reopening of outdoor hospitality. From 3 May 2021 gyms and leisure centres can reopen, extended households will be possible, children’s indoor activities and organised indoor activities for up to 15 people can begin again. -

Joint Statement from First Ministers of Wales And

Joint statement from First Ministers of Wales and Scotland in reaction to the EU (Withdrawal) Bill Responding to the introduction of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill, First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon and First Minister of Wales Carwyn Jones have today issued a joint statement. Thursday 13 July 2017 This week began with the Prime Minister calling for a constructive and collaborative approach from those outside Whitehall to help get Brexit right. Today’s publication of The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill is the first test as to whether the UK government is serious about such an approach. It is a test it has failed utterly. “We have repeatedly tried to engage with the UK government on these matters, and have put forward constructive proposals about how we can deliver an outcome which will protect the interests of all the nations in the UK, safeguard our economies and respect devolution. “Regrettably, the bill does not do this. Instead, it is a naked power-grab, an attack on the founding principles of devolution and could destabilise our economies. “Our 2 governments – and the UK government – agree we need a functioning set of laws across the UK after withdrawal from the EU. We also recognise that common frameworks to replace EU laws across the UK may be needed in some areas. But the way to achieve these aims is through negotiation and agreement, not imposition. It must be done in a way which respects the hard-won devolution settlements. “The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill does not return powers from the EU to the devolved administrations, as promised. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................ -

Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints

Published 23 March 2021 SP Paper 997 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Published in Scotland by the Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body. All documents are available on the Scottish For information on the Scottish Parliament contact Parliament website at: Public Information on: http://www.parliament.scot/abouttheparliament/ Telephone: 0131 348 5000 91279.aspx Textphone: 0800 092 7100 Email: [email protected] © Parliamentary copyright. Scottish Parliament Corporate Body The Scottish Parliament's copyright policy can be found on the website — www.parliament.scot Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints To consider and report on the actions of the First Minister, Scottish Government officials and special advisers in dealing with complaints about Alex Salmond, former First Minister, considered under the Scottish Government’s “Handling of harassment complaints involving current or former ministers” procedure and actions in relation to the Scottish Ministerial Code. [email protected] Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints Report of the Committee on the Scottish Government Handling of Harassment Complaints, 1st Report 2021 (Session 5) Committee -

Survey Report

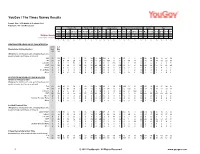

YouGov / The Times Survey Results Sample Size: 1100 Adults in Scotland (16+) Fieldwork: 4th - 8th March 2021 Vote in 2019 EU Ref 2016 Indy Ref Voting intention Holyrood Voting intention Gender Age Total Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Remain Leave Yes No Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Con Lab Lib Dem SNP Male Female 18-24 25-49 50-64 65+ Weighted Sample 1100 205 152 78 366 568 283 415 514 176 145 42 418 182 145 52 438 529 571 143 435 274 249 Unweighted Sample 1100 226 157 82 416 602 277 395 504 191 143 47 434 199 148 54 456 522 578 145 433 287 235 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % WESTMINSTER HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION 6-10 4-8 Westminster Voting Intention Nov Mar '20 '21 [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 23 84 7 8 1 17 40 4 40 100 0 0 0 93 6 3 0 25 20 12 16 27 32 Lab 17 17 5 64 20 5 19 16 8 27 0 100 0 0 3 88 11 2 16 18 18 15 20 19 Lib Dem 4 5 1 4 52 1 5 5 2 8 0 0 100 0 2 1 78 1 4 6 3 6 4 5 SNP 53 50 3 18 17 90 56 32 83 20 0 0 0 100 0 2 4 95 48 52 57 57 46 40 Green 3 3 0 6 3 2 3 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 2 3 3 6 4 1 2 Brexit Party 3 1 5 1 0 0 1 4 2 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 3 0 0 2 2 1 Other 1 1 2 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 3 1 0 1 HOLYROOD HEADLINE VOTING INTENTION Holyrood Voting Intention [Weighted by likelihood to vote, excluding those who would not vote, don't know, or refused] Con 19 22 80 6 18 1 18 38 4 39 93 3 10 0 100 0 0 0 25 19 13 17 24 31 Lab 15 17 10 59 15 4 17 18 8 26 5 87 4 1 0 100 0 0 17 16 14 14 20 18 Lib Dem 6 6 2 6 47 1 5 6 1 10 1 3 78 0 0 0 100 0 5 7 4 5 8 6 SNP 56 52 3 -

15 May 2018 Nicola Sturgeon MSP First Minister of Scotland Leader of the Scottish National Party Dear First Minister, RE

62 Britton Street London, EC1M 5UY United Kingdom T +44 (0)203 422 4321 @privacyint www.privacyinternational.org 15 May 2018 Nicola Sturgeon MSP First Minister of Scotland Leader of the Scottish National Party Dear First Minister, RE: Self-regulation of voter targeting by political parties We are all concerned by the misuse of people’s data by technology giants and data analytics companies. At Privacy International, we work across the world to expose and minimize the democratic impact of such practices. Consequently, with the UK Data Protection Bill, we urged parliamentarians, through all the stages to delete the wide exemption, open to abuse, that allows political parties to process personal data ‘revealing political opinions’ for the purposes of their political activities. To no avail – this provision stays in the Bill. The recent revelations regarding misuse of our data by Cambridge Analytica, facilitated by Facebook has shown that our concerns are justified and the problem is systemic. Cambridge Analytica and Facebook are not alone. The use of data analytics in the political arena needs to be strictly regulated. Personal data that might not have previously revealed political opinions can now be used to infer such opinions (primarily through profiling). Failure to act can lead to political manipulation and risks undermining trust in the democratic process. We believe the Scottish National Party shares this concern. As Brendan O’Hara MP stated “… the days of the unregulated, self-policing, digital Wild-West, wherein giant tech companies and shadowy political organisations can harvest, manipulate, trade in and profit from the personal data of millions of innocent, unsuspecting people, could be coming to an end”. -

Spice Briefing

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament Infor mation C entre l ogos. SPICe Briefing Scotland Bill: Regulated Social Fund 08 December 2015 15/80 Camilla Kidner The Regulated Social Fund will be devolved to the Scottish Parliament under the Scotland Bill, currently progressing through Westminster. The Regulated Social Fund is made up of: Funeral Payments, Sure Start Maternity Grant, Cold Weather Payments and the Winter Fuel Payment. This briefing gives an overview of these benefits and the debate so far over their devolution. It also looks briefly at proposals to devolve other measures related to welfare foods and fuel poverty. The Scottish Government intends to publish a paper in the new year setting out its social security proposals. Should the SNP be successful at the Scottish Parliament election in May 2016, a Social Security Bill will be introduced in the first year of the next Scottish Parliament. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 BACKGROUND............................................................................................................................................................ 4 EXPENDITURE ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 WINTER FUEL PAYMENT ..........................................................................................................................................