Arxiv:1710.05930V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Exoplanet-Host Star Ι Horologii: an Evaporated Member of the Primordial Hyades Cluster

A&A 482, L5–L8 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20079342 & c ESO 2008 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor The exoplanet-host star ι Horologii: an evaporated member of the primordial Hyades cluster S. Vauclair1,M.Laymand1, F. Bouchy2, G. Vauclair1,A.HuiBonHoa1, S. Charpinet1, and M. Bazot3 1 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Toulouse-Tarbes, CNRS, Université de Toulouse, 14 Av. Ed. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 75014 Paris, France 3 Centro de Astrophysica da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal Received 30 December 2007 / Accepted 4 March 2008 ABSTRACT Aims. We show that the exoplanet-host star iota Horologii, alias HD 17051, which belongs to the so-called Hyades stream, was formed within the primordial Hyades stellar cluster and has evaporated towards its present location, 40 pc away. Methods. This result has been obtained unambiguously by studying the acoustic oscillations of this star, using the HARPS spectrom- eter in La Silla Observatory (ESO, Chili). Results. Besides the fact that ι Hor belongs to the Hyades stream, we give evidence that it has the same metallicity, helium abun- dance, and age as the other stars of the Hyades cluster. They were formed together, at the same time, in the same primordial cloud. Conclusions. This result has strong implications for theories of stellar formation. It also indicates that the observed overmetallicity of this exoplanet-host star, about twice that of the Sun, is original and not caused by planet accretion during the formation of the planetary system. Key words. -

Superflares and Giant Planets

Superflares and Giant Planets From time to time, a few sunlike stars produce gargantuan outbursts. Large planets in tight orbits might account for these eruptions Eric P. Rubenstein nvision a pale blue planet, not un- bushes to burst into flames. Nor will the lar flares, which typically last a fraction Elike the Earth, orbiting a yellow star surface of the planet feel the blast of ul- of an hour and release their energy in a in some distant corner of the Galaxy. traviolet light and x rays, which will be combination of charged particles, ul- This exercise need not challenge the absorbed high in the atmosphere. But traviolet light and x rays. Thankfully, imagination. After all, astronomers the more energetic component of these this radiation does not reach danger- have now uncovered some 50 “extra- x rays and the charged particles that fol- ous levels at the surface of the Earth: solar” planets (albeit giant ones). Now low them are going to create havoc The terrestrial magnetic field easily de- suppose for a moment something less when they strike air molecules and trig- flects the charged particles, the upper likely: that this planet teems with life ger the production of nitrogen oxides, atmosphere screens out the x rays, and and is, perhaps, populated by intelli- which rapidly destroy ozone. the stratospheric ozone layer absorbs gent beings, ones who enjoy looking So in the space of a few days the pro- most of the ultraviolet light. So solar up at the sky from time to time. tective blanket of ozone around this flares, even the largest ones, normally During the day, these creatures planet will largely disintegrate, allow- pass uneventfully. -

Bibliography from ADS File: Lambert.Bib August 16, 2021 1

Bibliography from ADS file: lambert.bib Reddy, A. B. S. & Lambert, D. L., “VizieR Online Data Cata- August 16, 2021 log: Abundance ratio for 5 local stellar associations (Reddy+, 2015)”, 2018yCat..74541976R ADS Reddy, A. B. S., Giridhar, S., & Lambert, D. L., “VizieR Online Data Deepak & Lambert, D. L., “Lithium in red giants: the roles of the He-core flash Catalog: Line list for red giants in open clusters (Reddy+, 2015)”, and the luminosity bump”, 2021arXiv210704624D ADS 2017yCat..74504301R ADS Deepak & Lambert, D. L., “Lithium in red giants: the roles of the He-core flash Ramírez, I., Yong, D., Gutiérrez, E., et al., “Iota Horologii Is Unlikely to Be an and the luminosity bump”, 2021MNRAS.tmp.1807D ADS Evaporated Hyades Star”, 2017ApJ...850...80R ADS Deepak & Lambert, D. L., “Lithium abundances and asteroseismology of red gi- Ramya, P., Reddy, B. E., Lambert, D. L., & Musthafa, M. M., “VizieR On- ants: understanding the evolution of lithium in giants based on asteroseismic line Data Catalog: Hercules stream K giants analysis (Ramya+, 2016)”, parameters”, 2021MNRAS.505..642D ADS 2017yCat..74601356R ADS Federman, S. R., Rice, J. S., Ritchey, A. M., et al., “The Transition Hema, B. P., Pandey, G., Kamath, D., et al., “Abundance Analyses of from Diffuse Molecular Gas to Molecular Cloud Material in Taurus”, the New R Coronae Borealis Stars: ASAS-RCB-8 and ASAS-RCB-10”, 2021ApJ...914...59F ADS 2017PASP..129j4202H ADS Bhowmick, A., Pandey, G., & Lambert, D. L., “Fluorine detection in hot extreme Pandey, G. & Lambert, D. L., “Non-local Thermodynamic Equilibrium Abun- helium stars”, 2020JApA...41...40B ADS dance Analyses of the Extreme Helium Stars V652 Her and HD 144941”, Reddy, A. -

The Drifting Star: Astronomers 'Listen' to an Exoplanet-Host Star and Find Its Birthplace 15 April 2008

The drifting star: Astronomers 'listen' to an exoplanet-host star and find its birthplace 15 April 2008 that move in the same direction. Previously, astronomers using an ESO telescope had shown that the star harbours a planet, more than 2 times as large as Jupiter and orbiting in 320 days. But until now, all studies were unable to pinpoint the exact characteristics of the star, and hence to understand its origin. A team of astronomers, led by Sylvie Vauclair from the University of Toulouse, France, therefore decided to use the technique of 'asteroseismology' to unlock the star's secrets. "In the same way as geologists monitor how seismic waves generated by earthquakes propagate through the Earth and learn about the inner structure of our planet, it is possible to study sound waves running through a star, which forms a sort of large, spherical bell," says Vauclair. Using HARPS on ESO's 3.6-m telescope at La Silla, astronomers were able to study in great detail the star The 'ringing' from this giant musical instrument Iota Horologii, known to harbour a giant planet, and provides astronomers with plenty of information make a very precise portrait of it: its temperature is 6150 about the physical conditions in the star's interior. K, its mass is 1.25 times that of the Sun, and its age is 625 million years. Moreover, the star is found to be more And to 'listen to the music', the astronomers used metal-rich than the Sun by about 50%. This means the one of the best instruments available. -

Scientific American

Medicine Climate Science Electronics How to Find the The Last Great Hacking the Best Treatments Global Warming Power Grid Winner of the 2011 National Magazine Award for General Excellence July 2011 ScientificAmerican.com PhysicsTHE IntellıgenceOF Evolution has packed 100 billion neurons into our three-pound brain. CAN WE GET ANY SMARTER? www.diako.ir© 2011 Scientific American www.diako.ir SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN_FP_ Hashim_23april11.indd 1 4/19/11 4:18 PM ON THE COVER Various lines of research suggest that most conceivable ways of improving brainpower would face fundamental limits similar to those that affect computer chips. Has evolution made us nearly as smart as the laws of physics will allow? Brain photographed by Adam Voorhes at the Department of Psychology, Institute for Neuroscience, University of Texas at Austin. Graphic element by 2FAKE. July 2011 Volume 305, Number 1 46 FEATURES ENGINEERING NEUROSCIENCE 46 Underground Railroad 20 The Limits of Intelligence A peek inside New York City’s subway line of the future. The laws of physics may prevent the human brain from By Anna Kuchment evolving into an ever more powerful thinking machine. BIOLOGY By Douglas Fox 48 Evolution of the Eye ASTROPHYSICS Scientists now have a clear view of how our notoriously complex eye came to be. By Trevor D. Lamb 28 The Periodic Table of the Cosmos CYBERSECURITY A simple diagram, which celebrates its centennial this 54 Hacking the Lights Out year, continues to serve as the most essential conceptual A powerful computer virus has taken out well-guarded tool in stellar astrophysics. By Ken Croswell industrial control systems. -

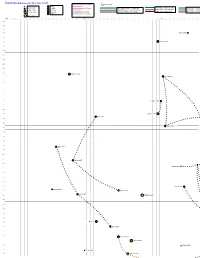

NSL3 Variant Map for 2300AD

2300AD Star Map based on Near Star List III Human Homeworld / Colony Homeworld -60 to -30 ly A Blue Human Outpost Trade Route - Chinese Arm -30 to -10 ly F White Kafer Homeworld / Colony Major Trade Route - Chinese Arm Other Route - Chinese Trade Route - American Arm -10 to +10 ly G Yellow Kafer Outpost Major Trade Route - American Arm Other Route - America Trade Route- French Arm +10 to +30 ly K Orange Ylii Homeworld / Colony Major Trade Route- French Arm Other Route- French A M Red Alien Homeworld / Colony +30 to +60 ly -60.0 -59.5 -59.0 -58.5 -58.0 -57.5 -57.0 -56.5 -56.0 -55.5 -55.0 -54.5 -54.0 -53.5 -53.0 -52.5 -52.0 -51.5 -51.0 -50.5 -50.0 -49.5 -49.0 -48.5 -48.0 -47.5 -47.0 -46.5 -46.0 -45.5 -45.0 -44.5 -44.0 -43.5 -43.0 -42.5 -42.0 -41.5 -41.0 -40.5 -40.0 -39.5 -39.0 -38.5 -38.0 -37.5 -37.0 -36.5 -36.0 -35.5 60.0 59.5 59.0 58.5 DM-13 2420 58.0 57.5 DM+22 1921 57.0 56.5 56.0 55.5 55.0 54.5 54.0 DM+21 1949 AC-1 409-15 53.5 53.0 52.5 52.0 51.5 51.0 DM+7 1997 50.5 50.0 49.5 DM+12 1888 Ross 686 49.0 48.5 DM-5 2603 48.0 47.5 47.0 46.5 46.0 DM-5 2778 45.5 45.0 44.5 DM+1 2277 44.0 DM-42 4577 43.5 43.0 42.5 42.0 41.5 DM+8 2131 DM-20 2936 41.0 DM+5 2143 DM-5 2802 40.5 DM+34 1949 40.0 39.5 39.0 38.5 38.0 37.5 Ross 84 37.0 DM-8 2689 36.5 36.0 AC+27 24424 35.5 DM+40 2208 35.0 DM-44 5200 34.5 Theta Antilae 34.0 DM+27 1775 2300AD Star Map based on Near Star List III Human Homeworld / Colony Homeworld -60 to -30 ly A Blue Human Outpost Trade Route - Chinese Arm -30 to -10 ly F White Kafer Homeworld / Colony Major Trade Route - Chinese Arm Other -

Kepler's Laws (ANSWER KEY)

Name: ____________________________ Date:____________________ Mr. Croom’s Physics Chapter 7: Rotational motion Kepler’s Laws (ANSWER KEY) Solve the following problems 1. (Serway, p. 253, #2) Does a planet in orbit around the sun travel at a constant speed? How do you know? No since the distance from the sun changes. 2. (Serway, p. 253, #3) Suppose you know the mean distance between both Mercury and the sun and Venus and the sun. You also know the period of Venus’s orbit around the sun. How can you find the period of Mercury’s orbit? Keepler’s 3rd Law 3. The planet shown below sweeps out Area 1 in half the time that the planet sweeps out Area 2. How much bigger is Area 2 than Area 1? 2 times as big. 4. (Giancoli, p 142, #55) Halley’s comet orbits the Sun roughly once every 76 years. It comes very close to the surface of the Sun on its closest approach. Estimate the greatest distance of the comet from the Sun. Is it still “in” the Solar System? What planet’s orbit is nearest when it is out there? [Hint: The mean distance s in Kepler’s third law is half the sum of the nearest and farthest distance from the Sun.] 5.4 x 1012 m, in the solar system, Pluto 5. (Walker, p. 379, #25) In July of 1999 a planet was reported to be orbiting the Sun-like star Iota Horologii with a period of 320 days. Find the radius of the planet’s orbit, assuming that Iota Horologii has the same mass as the Sun. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Travis S. Metcalfe White Dwarf Research

CURRICULUM VITAE Travis S. Metcalfe White Dwarf Research Corporation, 9020 Brumm Trail, Golden CO 80403 USA phone: 720-310-5180 / email: [email protected] / web: travis.wdrc.org EDUCATION 2001 Ph.D., Astronomy, University of Texas at Austin 1996 B.S., Astronomy & Physics, University of Arizona EXPERIENCE White Dwarf Research Corporation 2021-present Executive Director & Senior Research Scientist 2015-2021 Senior Research Scientist, Center for Solar-Stellar Connections Space Science Institute 2015-2021 Senior Research Scientist, Center for Extrasolar Planetary Systems 2012-2015 Research Scientist, Center for Extrasolar Planetary Systems National Center for Atmospheric Research 2009-2012 Scientist II, High Altitude Observatory & Technology Development Division 2006-2009 Scientist I, High Altitude Observatory & Scientific Computing Division 2004-2006 NSF Astronomy & Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellow Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics 2002-2004 CfA Postdoctoral Fellow Theoretical Astrophysics Center, Aarhus University, Denmark 2001-2002 TAC Postdoctoral Fellow HONORS 2019 AAS Fellow, American Astronomical Society 2017 Science Enterprise Reporting Award, Society of Professional Journalists 2005-present Google grant, White Dwarf Research Corporation (whitedwarf.org) 1999-2001 Co-chair, Graduate Student Assembly, University of Texas at Austin 1997 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, Honorable Mention 1995-1996 Undergraduate Research Fellowship, Honors Center, University of Arizona 1994-1996 Goldwater National Scholarship, University of Arizona -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

Galpy Documentation Release V1.4.1 Jo Bovy

galpy Documentation Release v1.4.1 Jo Bovy Aug 21, 2019 Contents 1 Quick-start guide 3 1.1 Installation................................................3 1.2 What’s new?...............................................8 1.3 Introduction............................................... 11 1.4 Potentials in galpy............................................ 25 1.5 A closer look at orbit integration..................................... 50 1.6 Two-dimensional disk distribution functions.............................. 74 1.7 Action-angle coordinates......................................... 97 1.8 Three-dimensional disk distribution functions.............................. 130 2 Tutorials 141 2.1 Dynamical modeling of tidal streams.................................. 141 3 Library reference 159 3.1 Orbit (galpy.orbit)......................................... 159 3.2 Potential (galpy.potential).................................... 205 3.3 actionAngle (galpy.actionAngle)................................. 299 3.4 DF (galpy.df)............................................. 309 3.5 Utilities (galpy.util)......................................... 371 4 Acknowledging galpy 403 5 Papers using galpy 405 6 Indices and tables 415 Index 417 i ii galpy Documentation, Release v1.4.1 galpy is a Python 2 and 3 package for galactic dynamics. It supports orbit integration in a variety of potentials, evaluating and sampling various distribution functions, and the calculation of action-angle coordinates for all static potentials. galpy is an astropy affiliated package and provides -

Bibliography Y

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The processing and evolution of dust in Herbig Ae/Be systems. Bouwman, J. Publication date 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bouwman, J. (2001). The processing and evolution of dust in Herbig Ae/Be systems. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 Bibliography y Adamss F.C, Lada C.|., Shu F.H., 1987. Spectral evolution of young stellar objects. Ap|312C88. Allamandolaa L,)., Lielens CG.M., Barker ).R., 1989. Interstellar polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbonss - The infrared emission bands, the excitation/emission mechanism, and thee astrophysical implications. ApJS71, 733. Allenn (I.C., Morris R.V., Lauer HA'., McKay D.S., 1993. Microscopic iron metal on glasss and minerals - A tool for studying regolith maturity. -

An Evaporated Member of the Primordial Hyades Cluster

A&A 482, L5–L8 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20079342 & c ESO 2008 Astrophysics Letter to the Editor The exoplanet-host star ι Horologii: an evaporated member of the primordial Hyades cluster S. Vauclair1,M.Laymand1, F. Bouchy2, G. Vauclair1,A.HuiBonHoa1, S. Charpinet1, and M. Bazot3 1 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Toulouse-Tarbes, CNRS, Université de Toulouse, 14 Av. Ed. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 75014 Paris, France 3 Centro de Astrophysica da Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal Received 30 December 2007 / Accepted 4 March 2008 ABSTRACT Aims. We show that the exoplanet-host star iota Horologii, alias HD 17051, which belongs to the so-called Hyades stream, was formed within the primordial Hyades stellar cluster and has evaporated towards its present location, 40 pc away. Methods. This result has been obtained unambiguously by studying the acoustic oscillations of this star, using the HARPS spectrom- eter in La Silla Observatory (ESO, Chili). Results. Besides the fact that ι Hor belongs to the Hyades stream, we give evidence that it has the same metallicity, helium abun- dance, and age as the other stars of the Hyades cluster. They were formed together, at the same time, in the same primordial cloud. Conclusions. This result has strong implications for theories of stellar formation. It also indicates that the observed overmetallicity of this exoplanet-host star, about twice that of the Sun, is original and not caused by planet accretion during the formation of the planetary system. Key words.