1 Globalization Without Markets?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography

arts Article Inverted Worlds, Nocturnal States and Flying Mammals: Bats and Their Symbolic Meaning in Moche Iconography Aleksa K. Alaica Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 19 Ursula Franklin Street, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2, Canada; [email protected] Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 10 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Bats are depicted in various types of media in Central and South America. The Moche of northern Peru portrayed bats in many figurative ceramic vessels in association with themes of sacrifice, elite status and agricultural fertility. Osseous remains of bats in Moche ceremonial and domestic contexts are rare yet their various representations in visual media highlight Moche fascination with their corporeal form, behaviour and symbolic meaning. By exploring bat imagery in Moche iconography, I argue that the bat formed an important part of Moche categorical schemes of the non-human world. The bat symbolized death and renewal not only for the human body but also for agriculture, society and the cosmos. I contrast folk taxonomies and symbolic classification to interpret the relational role of various species of chiropterans to argue that the nocturnal behaviour of the bat and its symbolic association with the moon and the darkness of the underworld was not a negative sphere to be feared or rejected. Instead, like the representative priestesses of the Late Moche period, bats formed part of a visual repertoire to depict the cycles of destruction and renewal that permitted the cosmological continuation of life within North Coast Moche society. Keywords: bats; non-human animals; Moche; moon imagery; priestess; sacrifice; agriculture; fertility 1. -

HOJA DE RUTA – ZONA 05 (Portada Del Sol (Av

HOJA DE RUTA – ZONA 05 (Portada del Sol (Av. El Corregidor) – Praderas de la Molina – Alameda del Corregidor – Cabo Linares) AV, JR, CALLE, PSJE CDRA. DE A HORA OBSERVACION Tienda Wong de Viñas 7:00 – 7:12 Av. El Corregidor 33 7:40 – 7:52 Inicio – Ruta Jr. Sierra Morena 01 7:41 – 7:53 Jr. Córdova 02 7:42 – 7:54 Calle Colmenares 01 – 03 7:43 – 7:55 Con retroceso Calle Colmenares 03 – 01 7:50 – 8:02 Bajada Jr. Córdova 02 7:52 – 8:04 Jr. Segovia 01 – 03 7:53 – 8:05 Subida (3ra Cuadra retroceso) Jr. Cataluña 02 7:57 – 8:09 Bajada Jr. Sierra Morena 02 7:59 – 8:11 Jr. Córdova 01 8:00 – 8:12 Calle Badajoz 01 – 02 8:02 – 8:14 Subida Jr. Cataluña 01 8:04 – 8:16 Calle Toledo 02 – 01 8:05 – 8:17 Bajada Jr. Córdova 01 8:06 – 8:18 Jr. Sierra Morena 01 8:06 – 8:19 Av. Corregidor 34 – 36 8:07 – 8:20 Calle Volcán PichuPichu 01 8:10 – 8:23 Subida Calle Volcán Chachani 02 8:12 – 8:25 Calle Volcán Sabancaya 02 8:13 – 8:26 Subida Calle Volcán Omate 01 8:15 – 8:28 Calle Volcán Coropuna 02 8:16 – 8:29 Retro 1 Cdra (Cdra 02) Calle Volcán Chachani 01 8:19 – 8:32 Calle Volcán Misti 01 8:20 – 8:33 Retro 01 – 02 (Reja) Calle Volcán Chachani 01 8:26 – 8:39 Calle Volcán Sabancaya 01 8:27 – 8:40 Bajada Av. Corregidor 37 8:30 – 8:43 Calle Río Amarillo 01 8:33 – 8:46 Subida en curva Calle Río Danubio 02 8:36 – 8:49 Subida Calle Río Níger S/N 8:39 – 8:52 Retro ½ Cdra. -

Evidencia Del Complejo Arqueológico Kuélap

El efecto de la inversion´ en infraestructura sobre la demanda tur´ıstica: evidencia del complejo arqueologico´ kuelap.´ Erick Lahura, Lucely Puscan y Rosario Sabrera* Resumen ¿Cu´ales el efecto de la inversi´onen infraestructura sobre la demanda tur´ıstica? Para responder a esta pregunta, se analiza el caso del Complejo Arqueol´ogico Ku´elap,el cual se ha beneficiado de la construcci´onde un sistema de telecabinas que ha hecho m´asaccesible y atractiva su visita desde su inauguraci´onen marzo del a~no2017. La hip´otesisque se plantea es que dicha inversi´onen infraestructura tur´ıstica ha tenido un efecto importante sobre la demanda tur´ıstica de Ku´elap.Para evaluar la validez de esta hip´otesis,se aplica un estudio de caso comparativo en el cual se utiliza un \control sint´etico" construido a partir de la informaci´onde los diferentes sitios arqueol´ogicos del Per´uentre los a~nos2008 y 2018. Este control sint´etico permite estimar cu´alhubiera sido la evoluci´onde las visitas a Ku´elapsi no se hubiera construido el sistema de telecabinas. Los resultados muestran que la inversi´onen infraestructura tur´ıstica en Ku´elapgener´oun aumento de aproximadamente 100 por ciento en el n´umero de visitas. En los ´ultimosa~nos,el turismo ha incrementado su importancia dentro de la econom´ıa,especialmente en pa´ısesen desarrollo Faber y Gaubert (2019). Seg´unla Organizaci´onMundial del Turismo (2019), dicha actividad genera cerca del 10 % del PBI mundial y crea 1 de cada 10 empleos en el mundo. En el Per´u,el turismo ha logrado una contribuci´onde cerca del 4 % al PBI nacional, seg´unreporta el Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo (2016). -

Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru

Tearing Down Old Walls in the New World: Reconsidering a Moche Site in Northern Peru Megan Proffitt The country of Peru is an interesting area, bordered by mountains on one side and the ocean on the other. This unique environment was home to numerous pre-Columbian cultures, several of which are well- known for their creativity and technological advancements. These cul- tures include such groups as the Chavin, Nasca, Inca, and Moche. The last of these, the Moche, flourished from about 0-800 AD and more or less dominated Peru’s northern coast. During the 2001 summer archaeological field season, I was granted the opportunity to travel to Peru and participate in the excavation of the Huaca de Huancaco, a Moche palace. In recent years, as Dr. Steve Bourget and his colleagues have conducted extensive research and fieldwork on the site, the cul- tural identity of its inhabitants have come into question. Although Huancaco has long been deemed a Moche site, Bourget claims that it is not. In this paper I will give a general, widely accepted description of the Moche culture and a brief history of the archaeological work that has been conducted on it. I will then discuss the site of Huancaco itself and my personal involvement with it. Finally, I will give a brief account of the data that have, and have not, been found there. This information is crucial for the necessary comparisons to other Moche sites required by Bourget’s claim that Huancaco is not a Moche site, a claim that will be explained and supported in this paper. -

LD5655.V856 1988.G655.Pdf (8.549Mb)

CONTROL OF THE EFFECTS OF WIND, SAND, AND DUST BY THE CITADEL WALLS, IN CHAN CHAN, PERU bv I . S. Steven Gorin I Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Environmental Design and Planning I APPROVED: ( · 44”A, F. Q. Ventre;/Chairman ‘, _/— ;; Ä3“ 7 B. H. Evans E2 i;imgold ___ _H[ C. Miller 1115111- R. P. Schubert · — · December, 1988 Blacksburg, Virginia CONTROL OF THE EFFECTS OF WIND, SAND, AND DUST BY THE CITADEL WALLS IN CHAN CHAN, PERU by S. Steven Gorin Committee Chairman: Francis T. Ventre Environmental Design and Planning (ABSTRACT) Chan Chan, the prehistoric capital of the Chimu culture (ca. A.D. 900 to 1450), is located in the Moche Valley close to the Pacific Ocean on the North Coast of Peru. Its sandy desert environment is dominated by the dry onshore turbulent ' and gusty winds from the south. The nucleus of this large durban community built of adobe is visually and spacially ' dominated by 10 monumental rectilinear high walled citadels that were thought to be the domain of the rulers. The form and function of these immense citadels has been an enigma for scholars since their discovery by the Spanish ca. 1535. Previous efforts to explain the citadels and the walls have emphasized the social, political, and economic needs of the culture. The use of the citadels to control the effects of the wind, sand, and dust in the valley had not been previously considered. -

Cusco 04 Days / 03 Nights

ASOCIACIÓN PERUANA DE OPERADORES DE TURISMO RECEPTIVO E INTERNO PERUVIAN ASSOCIATION OF INCOMING TOUR OPERATORS III Cumbre América del Sur - Países Árabes (ASPA) February 16, 2011 LIMA - PERU CODE PROGRAM DEPARTURE DATES Apo17-ASPA-2-11 A View of Cusco * Apo18-ASPA-2-11 Wonders of Cusco * Apo19-ASPA-2-11 Northern Peru: Moche Route: Chiclayo & Trujillo * Apo20-ASPA-2-11 Nazca Lines & Paracas * Apo21-ASPA-2-11 Iquitos & the Amazon * Apo22-ASPA-2-11 Delfin River Cruise–Amazon River * Apo23-ASPA-2-11 Delfin II River Cruise–Amazon River * Apo24-ASPA-2-11 Aqua River Cruise–Amazon River * *Programs could be booked before or after the III ASPA Event ASOCIACIÓN PERUANA DE OPERADORES DE TURISMO RECEPTIVO E INTERNO PERUVIAN ASSOCIATION OF INCOMING TOUR OPERATORS A VIEW OF CUSCO Apo17-ASPA-2-11 (03 days / 02 nights) DAY 01 LIMA - CUSCO (D) Upon your arrival, reception and transfer to your hotel in Cusco, the ancient capital of the Inca Empire. Coca tea is widely offered at the hotels as it helps relieve altitude sickness. Balance of the morning at leisure to relax and gradually adjust to the altitude. Your comprehensive afternoon tour includes the beautiful Koricancha or Sun Temple, the Cathedral, as well as the impressive Fortress of Sacsayhuaman and the amphitheater of Kenko. This is followed by a visit to Puca Pucara, a strategically located 'red fortress' that dominates the entire area before visiting Tambomachay, with its two distinctive aqueducts that to this day continue to provide clean water to the area. Welcome dinner show. Overnight (selected hotel). DAY 02 CUSCO - MACHU PICCHU - CUSCO (B,L) In the morning, transfer to the train station of Poroy or Ollantaytambo, to board the train to the marvelous citadel of Machu Picchu. -

Late Miocene -Quaternary Forearc Uplift In

Late Miocene - Quaternary forearc uplift in southern Peru: new insights from 10 Be dates and rocky coastal sequences Vincent Regard, Joseph Martinod, Marianne Saillard, Sébastien Carretier, Laëtitia Leanni, Laurence Audin, Kevin Pedoja To cite this version: Vincent Regard, Joseph Martinod, Marianne Saillard, Sébastien Carretier, Laëtitia Leanni, et al.. Late Miocene - Quaternary forearc uplift in southern Peru: new insights from 10 Be dates and rocky coastal sequences. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, Elsevier, 2021, 8th ISAG Special Issue, 109, pp.103261. 10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103261. hal-03162682 HAL Id: hal-03162682 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03162682 Submitted on 8 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Late Miocene - Quaternary forearc uplift in southern Peru: new insights from 10Be dates and rocky coastal sequences 5 Vincent Regard1*, Joseph Martinod2, Marianne Saillard3, Sébastien Carretier1, Laetitia Leanni4, Gérard Hérail1, Laurence Audin2, Kevin Pedoja5 1. Géosciences Environnement Toulouse/OMP, Université de Toulouse, CNES, CNRS, IRD, UPS, Toulouse, France 2. Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Univ. Savoie Mont Blanc, CNRS, IRD, IFSTTAR, ISTerre, Grenoble, France. 10 3. Université Côte d'Azur, IRD, CNRS, Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, Géoazur, 250 rue Albert Einstein, Sophia Antipolis 06560 Valbonne, France. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

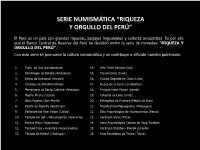

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

Acta I Congreso Volumen I

ACTAS I CONGRESO NACIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA VOLUMEN I ACTAS I CONGRESO NACIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA VOLUMEN I PONENCIA MAGISTRAL SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA COSTA NORTE SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA COSTA CENTRAL SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA COSTA SUR Índice Jorge Nieto Montesinos VOLUMEN I El Camino Inca de la costa en Tumbes 103 Incahuasi, Cañete: resultados preliminares 227 Ministro de Cultura Carolina Vílchez Carrasco de la temporada 2013 Prólogo 5 Alejandro Chu Ana Castillo Aransaenz Viceministra de Patrimonio Cultural Presentación 7 SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA DE LA COSTA CENTRAL SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA e Industrias Culturales DE LA COSTA SUR El patrimonio arqueológico de la civilización Caral 115 y el desarrollo social integral y sostenible en el área Investigaciones del Programa Arqueológico 237 PONENCIA MAGISTRAL norcentral del Perú Chincha: temporada 2013 Ruth Shady Solís / Carlos Leyva Henry Tantaleán / Charles Stanish / El urbanismo moche y el surgimiento 9 Alexis Rodríguez / Kelita Pérez del Estado y la ciudad en los Andes centrales Avance de las excavaciones arqueológicas 141 Santiago Uceda C. / Jorge Meneses B. en la Huaca Pucllana en la temporada 2013 La arquitectura Paracas en Ánimas Altas/ 247 Isabel Flores Espinoza Ánimas Bajas, valle de Ica: técnicas y semántica SIMPOSIO REGIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGÍA Aïcha Bachir Bacha DE LA COSTA NORTE El uso de reconstrucciones 3D en la arqueología 153 doméstica: Una aproximación a través Comunidad, tradición y reforma sociopolítica 259 Excavaciones en el sitio de Huerequeque, 19 del sitio arqueológico de Panquilma en Nasca Tardío valle de Casma (2009-2014) Enrique López-Hurtado Ojeda / Luis Manuel González La Rosa / Verity H. -

Moche Route – the Lost Kingdoms

MOCHE ROUTE – THE LOST KINGDOMS MAY 2019 MON 20 CIVILIZATIONS AT NORTHERN PERU: MOCHE AND CHIMU (L,D) 10:40 Airport pick up. 11:15 Visit to Site Museum at Huaca de la Luna, where you can admire a great collection of beatiful pottery and its iconography, created by Moche people. The tour continues to the archaeologycal area, a huge monument that exhibits colorful mural on decorated wall. This construction represents one of the most important and magnificient edifications of ancient Perú. 13:30 Seafood buffet at Huanchaco beach. 14:15 Vivential experience admiring typical fishing boats called “caballitos de totora”. Made of totora fiber, these ancient boats are still used every day by local fishermen. You can also experience a ride in one of these boats. 15:15 Visit to Chan Chan – Biggest mud city in the world, Cultural heritage of humanity. Built by Chimu inhabitants (700 dC – 1500 dC) is an impressive edification with very high walls, friezes and designs of great urban planification. 17:00 Hotel check in 20:00 Dinner TUE 21 THE AMAZING TREASURES OF THE LORD OF SIPAN (B, L) 06:15 Buffet breakfast 06:45 We´ll head to Magadalena de Cao, 70 kms. north of Trujillo, a few minutes from the shore, first stop to visit El Brujo complex. We´ll visit first the archaeolgycal zone, similar style to Huaca de la Luna, but different murals. We´ll continue to visit Cao Museum that shows the incredible and excellent preserved mummy of one of female governors of Moche culture, called Lady of Cao. -

Of Priests and Pelicans: Religion in Northern Peru

Of Priests and Pelicans: Religion in Northern Peru Kennedi Bloomquist I am standing in the far corner of the Plaza des Armas, excitement racing through my chest. Along the roads surrounding the plaza are long brilliant murals made of colorful flower petals lined with young school girls in bright red jumpsuits, their eyes following my every movement. A cool breeze whips around stirring the array of magenta, turquoise, royal purple, orange and various shades of green petals. 20 tall arches placed between the various flower murals are covered with bright yellow flowers (yellow symbolizes renewal and hope) spotted with white (white symbolizes reverence and virtue) and fuchsia (fuchsia symbolizes joy) roses. A stage has been erected in the street in front of the mustard yellow Trujillo Cathedral. In the center of the stage is an altar with a statue of Christ on the cross with an elaborate motif hanging on the back wall with angels carrying a large ornate crown. A band plays loud and wildly out of tune Christian salsa music to the side of the stage. A large golden sign reading Corpus Christi sits along the top of the building sidled up against the Cathedral. The feeling permeating throughout the square is carefree and peaceful. As I wander through the crowd, I cannot stop smiling at all the people dancing, shaking their hands to the sky. Some spin in circles, while others just clap their hands smiling towards the heavens. Next to me an older woman in a simple church outfit with a zebra print scarf holds a JHS (Jesus Hominum Savitore) sign in one hand and reaches for the sky with her other hand, shuffling back and forth.