Cross-Border Practices and Transnational Identifications Among EU and Third-Country Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waldhaus Dinner Summer.Indd

Fondue s e r v e s t w o Beef double beef consommé / sliced alberta beef steamed vegetables / new potatoes / dipping sauces 70 add 4 prawns 10 add 4 scallops 12 Truff le gruyère / emmental / white wine / kirsch / black truffl e steamed vegetables / new potatoes / crusty bread 56 add air cured meat platter 12 Swiss gruyère / emmental / white wine / kirsch steamed vegetables / new potatoes / crusty bread 54 add air cured meat platter 12 Spezialitäten s p e c i a l t i e s Veal Zurichoise veal emincée / rösti potato / morel & cremini mushrooms market vegetables / riesling cream sauce 35 Wiener Schnitzel breaded & pan fried veal escalope / shoestring potatoes braised red cabbage / veal glaze 32 Sunhaven Farms Pork Tenderloin candied walnut crust / cippolini onion & potato purée braised red cabbage / apple preserve / sauce forestière 32 Beyond the Foothills from the rocky mountains to the alberta badlands, this diverse landscape is home to a number of both sustainable and organic farms. as part of fairmont’s commitment to environmental stewardship, this menu contains locally sourced items from fairwinds, broxburn and hotchkiss farms. in addition, we feature gourmet food products such as valbella cured meats and sylvan star cheese. Wörterbuch d i c t i o n a r y Spätzle: “little sparrow”; a traditional egg noodle of soft texture used in central european cuisine Rohesspeck: smoked, cured bacon Zurichoise: cuisine from the region of zurich, switzerland Rösti: grated potato shaped into a round and pan fried in butter Beilage s i d e d i s h cheese -

To View Online Click Here

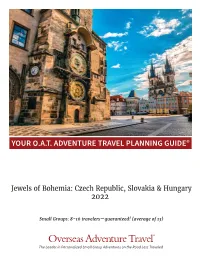

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Jewels of Bohemia: Czech Republic, Slovakia & Hungary 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Jewels of Bohemia: Czech Republic, Slovakia & Hungary itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: In my mind, there is nothing more quaint and picturesque than the rural villages that dot the countryside of the Czech Republic. To immerse myself in their traditions and everyday life, I explore rural communities like Slavonice, a small village nestled on the border with Austria. You’ll see what I mean when you experience A Day in the Life of a small, family-run farm here, where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the owners, lend a hand with the daily farm chores, and share a Home-Hosted Lunch with your hosts around the warmth of a bonfire. I believe the most moving stories you’ll hear are from the locals who live and work in the regions you travel to around the world, and that is what I found to be true in Prague when I spoke with Zdenek Vacek, a local teacher and lifelong Prague resident, about the Velvet Revolution. I was saddened to hear the reality of their turbulent past under the Czech Communist regime. -

Well Fed PDF Sampler

paleo welLrecipes FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE TO EAT BY melissa joulwan PHOTOgraphy BY David Humphreys forewOrd BY Melissa & Dallas Hartwig FEd Whole9 weLlpaleo recipes for people FEd who love to eat By Melissa Joulwan Foreword by Melissa and Dallas Hartwig Photos by David Humphreys Design by Kathleen Shannon ISBN Well Fed: Paleo Recipes for People Who Love to Eat Copyright ©2011 Melissa Joulwan. All rights reserved. No part of this book my be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Well Fed: Paleo Recipes for People Who Love to Eat Author: Melissa Joulwan Foreword: Melissa and Dallas Hartwig Copy Editor: Alison Finney Assistant Copy Editor: Walker Fenz Photography: David Humphreys Illustrations: David Humphreys Design: Kathleen Shannon ISBN 10: 0-615-57226-X To the entire Joulwan and Stramara clans – and the spirit ISBN 13: 978-0-615-57226-0 of my Sitti – for all the food and love, and food-love Published by: Smudge Publishing, LLC 405 El Paso Street And to my husband Dave, who is my favorite dinner companion Austin, TX 78704 www.smudgepublishing.com FOREWORD “You don’t have to cook fancy or treats and sweets are a normal part of most peoples’ sustainable THANK YOU complicated masterpieces – just diet, but we don’t need yet another “healthy” brownie recipe. We need inspiration to make our everyday food new, fresh, and exciting. To Bethany Benzur, for bringing us together with Kathleen Shannon good food from fresh ingredients.” That’s why almost all of the Well Fed recipes are Whole30 approved, - Julia Child perfect for both our nutrition program and your everyday meals. -

Fallow Buck Hunt in Slovakia. Free Range

ST HUBERTUS HUNTING TOURS HUNTING SEASON 2020-2021 FALLOW BUCK HUNT IN SLOVAKIA FREE RANGE Fallow buck hunting season in Slovakia: from the last week of August to mid January. The best period is October during mating season especially if you wish to hunt bucks with strong trophies. Hunt during winter months can be gripping and successful as well with now on terrains. Hunting areas Slovakia offers countless hunting areas in different districts of the country. Only few countries in Europe can compete with Slovakia in terms of variety of grounds and games. Level, hilly and mountainous grounds rich with varied flora and excellent populations of games. 25 hunting areas located in all the mountain chains of the country from west to east and from north to south, hilly areas with breath-taking panoramas and alluvial plains with deep forests and fields. The two hunting areas of this offer are sizing around 8000 ha of free/range grounds and are located in central-southern area of Slovakia near Rimaská Sobota, approximately 250 km from the capital city Bratislava. The areas are mainly covered by forests (over 40%) with majority of leafy trees. This areas offer a very good fallow deer population, every year several strong bucks are hunted there, maximum was of 4,1 kg (196 CIC). Jonathan Travel St. Hubertus Hunting tours [email protected] +420 776 708 813 TROPHIES 3 Accommodation Set in Rimavská Sobota, the Hotel Penzion provide a comfortable stay and offers a restaurant. There is a terrace and guests can make use of free WiFi and free private parking. -

Croatian Eno-Gastronomy Don´T Fill Your Life with Days, Fill Your Days

Free Croatian Eno-Gastronomy Full of flavours Don´t fill your life with days, fill your days with life. photo by ivo pervan ivo by photo discover your story at croatia.hr Introduction Croatia, Gastronomic Princess of the Mediterranean and Europe 4 The country of culinary diversity 10 Why enjoy Croatia? 12 Regions (Gastronomy, Health, About wine) List of regions 14 1_Istria 16 2_Kvarner 24 3_Lika_Karlovac 32 4_Dalmatia_Zadar 38 5_Dalmatia_Šibenik 44 6_Dalmatia_Split 50 7_Dalmatia_Dubrovnik 56 8_Slavonia 64 9_Central Croatia 72 10_Zagreb 78 About wine and special subjects About wine_Croatia – a small country for great wines 86 Olive oils_Benefits of olive oil 88 Water_Water is life 90 Ecological products 92 Information Basic information about Croatia 94 Offices of the Croatian National Tourist Board 95 c o n t e n t s Acknowledgements 96 4 c roatia, Gastronomic Princess of the Mediterranean Veljko Barbieri and Europe In the mid nineties, during the rescue excavations in Starograd- nonian influences, it condenses a soupy experience of goulash sko Polje (old town field) on the island of Hvar, grape and olive and stews with a special kaleidoscope of vegetables and spices, seeds were found in one of the funeral urns. Researchers specu- and of course wine, without which this unique dish can neither lated that this was a common residue of agricultural crops from be prepared nor enjoyed. The dish can be spiced during cooking the 4th or 3rd century BC as it was thought that both cultures or later adjusted to taste when already seated at the table, with were connected to the arrival of the Greeks and the establish- spices and wine such as Slavonian Traminac or Klikun, indige- ment of their colonies on the eastern coast. -

Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie with William R

Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie With William R. Thibodeaux Ph.D. ii | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | iii Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie With William R. Thibodeaux Ph.D. iv | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | v Contents Preface ix Culinary Foundations Chapter 1: Professionalism and Sauté 1 Chapter 2: Recipe conversions and Braising 27 Chapter 3: Lab - Mise en Place 33 Chapter 4: Food Presentation, Standards, and Grilling 41 Chapter 5: Emulsions and Steaming 69 Chapter 6: Cajun Creole Cuisine and Roux 75 Chapter 7: The Menu and Poaching 87 Chapter 8: Frying 99 Chapter 9: Flavor and Taste 105 Chapter 10: Breakfast and Roasting 151 Notes: 175 Glossary: 179 Appendix: 211 Kitchen Weights & measurements 213 Measurement and Conversion Charts 215 Basic Cooking Methods 217 Knife Cuts 224 Professional Associations 225 vi | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | vii Limit of Liability/disclaimer of warranty and Safety: The user is expressly advised to consider and use all safety precautions described in this book or that might be indicated by undertaking the activities described in this book. Common sense must also be used to avoid all potential hazards and, in particular, to take relevant safety precautions concerning likely or known hazards involving food preparation, or in the use of the procedures described in this book. In addition, while many rules and safety precautions have been noted throughout the book, users should always have adult supervision and assistance when working in a kitchen or lab. Any use of or reliance upon this book is at the user's own risk. While the information contained in this book has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable and correct at the time of original publication, neither the publisher nor the author makes any warranty, express or implied, with respect to the use of any techniques, suggestions, and ideas disclosed in this book. -

The Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet

The Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet Item Type Thesis Authors Cleek, Kathryn Download date 03/10/2021 21:32:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10484/12126 Cleek 1 The Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet Kathryn Cleek GH 401 November 27, 2015 Cleek 2 Abstract Introduction This thesis is over the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet, what causes these increase in health benefits. In the introduction of this paper I discuss what the Mediterranean diet is, the history of the Mediterranean diet, who first demonstrated the diet, the physical activity differences in America and Europe, the portion size differences and the Ten Commandments of the diet. Each component of diet is important for understand how the diet works when comparing it to the health of those who demonstrate the diet. Main Body The main body is composed of what I used to find my unknowns in the thesis. I use the information I was able to fine to answer my questions on the through my field research study, unknown and puzzling concerns, the differences between the Mediterranean diet and other diets, research, clinical trials and studies that have been completed, and the main Components and their chief health benefits. The findings were remarkable and was used to form my conclusion. Conclusions My findings concluded that the reason the Mediterranean diet is so beneficial is because of the preparation, the fresh food and ingredients, the controlled portion sizes, the increase in physical active and surrounding each other with family. It is a lifestyle, not a diet, that makes the biggest change on people health. -

A Poet's Restaurant Reviews in Early 1990S Prague

CULINARY REVOLUTIONS: FOOD, HISTORY, AND IDENTITY IN RUSSIA AND EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE | Abigail Weil, Harvard University To Revive Delight: A Poet’s Restaurant Reviews in Early 1990s Prague Abstract: In 1993, the Prague-based newspaper Lidové noviny (The I find that they are consistent with the restorative nature of the Czech People’s News) ran a short-lived restaurant review column, Básník má political and economic transition after communism. To Král, the res- hlad (The Poet Is Hungry). The author was Petr Král, a poet and essay- taurant represents a microcosm of society. Thus, in the spirit of restora- ist who had recently returned to Prague after two decades of exile in tion and revitalization, he elevates the genre of restaurant reviews, Paris. In this article, I contextualize Král’s restaurant reviews within his infusing them with political urgency and a sense of poetry. oeuvre and in the history of Czech restaurant culture. The first half describes the evolution of restaurants in Czech culture and literature from the First Czechoslovak Republic through the communist period. Keywords: Prague, restaurant reviews, postcommunism, poetry, The second half is devoted to close readings of Král’srestaurantreviews. surrealism ANYONE WHO HAS BEEN TO Prague in recent years will have a normal restaurant, even if they defended themselves, they would still “ š ů ” enjoyed a vibrant restaurant industry. In addition to Czech endeavor to appease the guest. ( Vinárna U rará k , October 2) restaurants whose sandwich boards beckon tourists with tradi- The excerpt comes from Král’s restaurant review series Básník tional Bohemian cuisine, one finds several exciting additions má hlad (The Poet Is Hungry), which ran sporadically in the to the culinary scene: three Michelin-starred establishments, weekend editions of the popular daily newspaper Lidové a multitude of international dining options, and a variety of noviny (The People’s News) from July through December of choices for the vegetarians who, until recently, were confined 1993. -

{365 Dining: Ramona Sunny Bakery & Delicatessen }

{ 365 dining: ramona sunny bakery & delicatessen } Ramona serves her Turkish coffee with a dash of Cardamom, a truly exotic spice that needs to be savored slowly. It is made from the seeds inside pods that are the fruit of a perennial herb related to ginger. It is called the Ramona Sunny Bakery & Delicatessen “Queen of Spices” and is the 3rd most by Rich Belmont expensive spice after saffron and vanilla. Cardamom tastes a little like a combination of ginger and cinnamon with a hint of lemon and mint. Ramona Sunny Bakery & Delicatessen 215 Diagonal Street, Galena, IL 61036 815-777-4364 / Facebook.com/RamonaSunnyBakery HOURS: Tue – Sat: 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun: 9 a.m. – 3 p.m., Mon: Closed DINING STYLE: Casual, Counter Service NOISE LEVEL: Conversational RECOMMENDATIONS: Turkish Coffee, All Pastries, Omelettes, Mushroom Soup, Meech, Hummus, Reuben, Italian Beef, Mediterranean Grilled Chicken Breast There is an intriguing little bakery and delicatessen right next to LIQUOR SERVICE: None PRICES: $2.75 - $10.95 Galena’s oldest home, the Dowling House, on Diagonal Street in PAY OPTIONS: Cash, Debit, Visa, MasterCard, Local Checks Galena, IL. It is called Ramona Sunny and is simply named after its ACCESSIBILITY: Ramp to Front Door & Restrooms The menu board boasts 8 exceptional sandwiches. They are all made owners, Ramona and Sunny Botezatu (Bow-tee-za-too). They came KIDS POLICY: No Menu, No High Chair, No Booster just the way you would expect from a delicatessen. The Tuna Spread to this country more than 30 years ago from Transylvania in the RESERVATIONS: No CATERING: No is homemade with cheese and onion. -

View Travel Planning Guide

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Jewels of Bohemia: Czech Republic, Slovakia & Hungary 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Jewels of Bohemia: Czech Republic, Slovakia & Hungary itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: In my mind, there is nothing more quaint and picturesque than the rural villages that dot the countryside of the Czech Republic. To immerse myself in their traditions and everyday life, I explore rural communities like Slavonice, a small village nestled on the border with Austria. You’ll see what I mean when you experience A Day in the Life of a small, family-run farm here, where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the owners, lend a hand with the daily farm chores, and share a Home-Hosted Lunch with your hosts around the warmth of a bonfire. I believe the most moving stories you’ll hear are from the locals who live and work in the regions you travel to around the world, and that is what I found to be true in Prague when I spoke with Zdenek Vacek, a local teacher and lifelong Prague resident, about the Velvet Revolution. I was saddened to hear the reality of their turbulent past under the Czech Communist regime. -

Din Tai Fung: Asia's Best-Loved Dumpling Heads to Europe

Din Tai Fung: Asia's best-loved dumpling heads to Europe edition.cnn.com/travel/article/din-tai-fung-dumplings-europe/index.html Katie Hunt, CNN 2018年12月18日 (CNN) — It takes just a few bites to see why Din Tai Fung, a Taiwan restaurant chain, has become the world's most celebrated purveyor of xiaolong bao -- pork soup dumplings. To the uninitiated, the plump, ping-pong ball sized dumplings might not look much but each is a tiny, slurpable work of culinary art. Sponsor content by Discover Budapest - Spice of Europe Divine food and fine wines in fabulous Budapest No longer just the home of warming stews and crisp, cold beer, Budapest is innovating and reinvigorating Central European cuisine into something dynamic and thoroughly internationa Puncture the delicate bundle, each folded with 18 intricate pleats, with your chopstick. Allow the soup to rush out onto your spoon, sip the exquisite juices and then bite through the skin into a delicious pork filling. Be warned it could lead to a life-long addiction. It did for me. I first encountered Din Tai Fung two decades ago as a student in Taipei when a friend introduced me to the chain's very first restaurant in an unassuming building on the city's Xinyi Road. In Hong Kong, where I lived for a decade, Din Tai Fung has earned a Michelin star -- a rare accolade for a relatively inexpensive chain restaurant. On moving to London this summer I was thrilled to discover that Din Tai Fung was launching its first European restaurant in the British capital, which opened in Covent Garden 1/4 in December. -

EUCROSS Final Report

www.ssoar.info The Europeanisation of Everyday Life: Cross- Border Practices and Transnational Identifications among EU and Third-Country Citizens - Final Report Recchi, Ettore (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Abschlussbericht / final report Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Recchi, E. (Ed.). (2014). The Europeanisation of Everyday Life: Cross-Border Practices and Transnational Identifications among EU and Third-Country Citizens - Final Report. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-395269 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use.