Uses of Tree Saps in Northern and Eastern Parts of Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Find Moths with Moth Traps

3.5 Sugaring Moth traps will attract the greatest variety of moths, but not all moths are equally attracted to light. Some can be observed using sugary bait instead. Moths come to “sugar” because they feed on nectar, sap and honeydew, all of which are unrefined sources of sugar (however, some moths do not feed as adults, and therefore will never be seen at sugar sources). The success of the technique is variable - warm humid nights with a light wind are best for sugaring (as they are for most forms of mothing), but the technique will also work on far from ideal nights, and not work on nights that seem good for no apparent reason. Ingredients 454g Tin of Black Treacle 1Kg Brown Sugar (the darker the better) 500ml Brown Ale or Bitter (fizzy drink like cola will do as an alternative) Paint brush. Slowly heat the ale (or cola) in a large pan and simmer for five minutes. Stir in and dissolve the sugar, followed by the treacle and then simmer for two more minutes. Allow to cool before decanting into a container. A drop of rum stirred in just before use is recommended but not essential. Paint the mixture about eye level onto 10- 20 tree trunks or fence posts just before dusk and check for moths by torch-light for the first two hours of darkness. A variation of this technique is “ wine roping ”. This works on a similar principle to the above. Ingredients Bottle of cheap red wine 1kg sugar 1m lengths of thick cord or light rope made from absorbent material. -

Sweetener Buying Guide

Sweetener Buying Guide The intent of this guide is purely informational. The summaries included represent the highlights of each sweetener and are not meant to be comprehensive. The traffic light system is not a dietary recommendation but a buying guideline. Sugar, in any form (even honey, maple syrup and dried fruit), can suppress the immune system and throw our bodies out of balance. It is important to consume sugar smartly. Start by choosing the best sweeteners for you. Then keep in mind that sugar is best reduced or avoided when your immune system is compromised e.g. - if you have candida overgrowth, are chronically stressed, fatigued or in pain, are diabetic or pre-diabetic, have digestive issues (IBS, Crohn’s etc.), etc... For more detailed information on how sweeteners can affect your body speak to one of our expert nutritionists on staff! The Big Carrot is committed to organic agriculture and as such prioritizes the organic version of all of these products. The organic logo is used below to represent those items that must be organic to be included, without review, on our shelves and in our products. Sweetener Definition Nutrition (alphabetical) Agave is a liquid sweetener that has a texture and appearance similar to honey. Agave Agave contains some fiber and has a low glycemic index syrup comes from the blue agave plant, the same plant that produces tequila, which grows compared to other sweeteners. It is very high in the Agave primarily in Mexico. The core of the plant contains aguamiel, the sweet substance used to monosaccharide fructose, which relies heavily on the produce agave syrup. -

Lvl) Having Different Patterns of Assembly

PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLE bioresources.com MECHANICAL PROPERTIES ANALYSIS AND RELIABILITY ASSESSMENT OF LAMINATED VENEER LUMBER (LVL) HAVING DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF ASSEMBLY a,b a, Bing Xue, and Yingcheng Hu * Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) panels made from poplar (Populus ussuriensis Kom.) and birch (Betula platyphylla Suk.) veneers were tested for mechanical properties. The effects of the assembly pattern on the modulus of elasticity (MOE) and modulus of rupture (MOR) of the LVL with vertical load testing were investigated. Three analytical methods were used: composite material mechanics, computer simulation, and static testing. The reliability of the different LVL assembly patterns was assessed using the method of Monte-Carlo. The results showed that the theoretical and ANSYS analysis results of the LVL MOE and MOR were very close to those of the static test results, and the largest proportional error was not greater than 5%. The veneer amount was the same, but the strength and reliability of the LVL made of birch veneers on the top and bottom was much more than the LVL made of poplar veneers. Good assembly patterns can improve the utility value of wood. Keywords: Laminated veneer lumber (LVL); Mechanical properties; Assembly pattern; Reliability; Poplar; Birch Contact information: a: Key Laboratory of Bio-based Material Science and Technology of Ministry of Education of China, College of Material Science and Engineering, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, 150040, China; b: Heilongjiang Institute of Science and Technology, Harbin, 150027, China; * Corresponding author: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Wood is a hard fibrous tissue found in many plants. It has many favorable properties such as its processing ability, physical and mechanical properties, and aesthetics, as well as being environmentally and health friendly. -

Cabot Creamery Cooperative Receives U.S. Dairy Sustainability

June 24, 2016 • Vol. 80, Num ber 6 Published monthly by the Vermont Agency of Agriculture • www.vermontagriculture.com Cabot Creamery Cooperative Receives U.S. Dairy Sustainability Award for Real Farm Power™ Program Effort to Reduce Food Waste and Energy Use Has Cows Providing Cream and Electricity for Cabot Butter By Laura Hardie, New England Dairy U .S . Dairy®, established under Promotion Board the leadership of dairy farmers, announced its fifth annual U .S . abot Creamery Cooperative Dairy Sustainability Awards during has been recognized with a a ceremony May 11 in Chicago . C2016 U .S . Dairy Sustainability The program recognizes dairy farms, Award for Outstanding Dairy businesses and partnerships whose Processing & Manufacturing sustainable practices positively Sustainability . The cooperative impact the health and well-being of was selected for its Real Farm consumers, communities, animals Power™ program which is the and the environment . latest in a series of sustainability Real Farm Power™ reduces projects pioneered by the 1,200 greenhouse gas emissions by 5,680 dairy-farm families of Agri-Mark tons annually while generating 2,200 dairy cooperative, owner of Cabot megawatt hours (MWh) of clean, Members of Cabot Creamery Cooperative accept the 2016 U.S. Dairy Creamery Cooperative . The program renewable energy per year to offset Sustainability Award for Outstanding Dairy Processing & Manufacturing takes a closed-loop approach, the power needed to make Cabot™ Sustainability in Chicago, Illinois on May 11, 2016. From Left to right: Amanda recycling cow manure, food scraps butter . The $2 .8 million project is Freund of Freund’s Farm Market and Bakery, Ann Hoogenboom of Cabot and food processing by-products expected to have a six-year payback, Creamery Cooperative, Steven Barstow II of Barstow’s Longview Farm, Phil to produce renewable energy on a and it offers a blueprint for scaling Lempert journalist and the Supermarket Guru, Caroline Barstow of Barstow’s Massachusetts dairy farm . -

Cusk Fishing Devices, Which Revealed Fish Swimming 20 Freshwater Fish in New Are Heavy Baited Lines Teth- Feet Beneath Us

VOLUME 35, NUMBER 42 MARCH 24, 2011 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Play Ball: Catch-M-All: Kennett High School Two local fishermen embark contributing writer on yearlong quest to catch Shawn Beattie previews and eat every species of 2011 KHS Baseball freshwater fish in N.H… A4 season … A2 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH Page Two Play Ball! A look into the 2011 baseball season at Kennett High School By Shawn Beattie and experience that the Eagles Kennett High School possess allow them to move Special to the Mountain Ear people around on defense and give guys rest, while maintain- AMERICA’S PAST TIME ing a strong team from game has returned. Major League to game. Baseball’s spring training has The Eagles did lose veteran been taking place for the past leaders like Jeff Sires and Mike couple of weeks as teams have Larson to graduation but lead- been playing exhibition games ership may not be an issue for in the Southern region of the the team. “As I’ve gone United States. As the snow through high school I have continues to slowly melt here realized every year that as a in New Hampshire, student player your responsibility athletes at Kennett High changes. Your team depends School begin packing their on you as a leader and a play- skis and sneakers away and er. I feel like I have been able dusting off their bats and to grow as an athlete both gloves. A large number of mentally and physically,” said boys gathered in the Kennett Jacobs. -

Non-Timber Forest Resources Information Compendium

Future Forest Products and Fibre Use Backgrounder: Non-Timber Forest Resources Information Compendium Prepared for: Omineca Beetle Action Coalition By: Ashley Kearns and Greg Halseth Community Development Institute University of Northern British Columbia January 2009 Future Forest Products and Fibre Use Backgrounder: Non-Timber Forest Resources in the OBAC Region Table of Contents Page Number About this Project iii Acknowledgements iv Project Availability v Contact Information v 1. Introduction 1 2. Agroforestry 3 2.1 Alley Cropping 6 2.2 Integrated Riparian Management and Timber Belting 8 2.3 Forest Farming 10 2.4 Silvopasture 12 3. Energy Production 14 3.1 Biomass Energy 16 4. Birch Products 19 5. Botanical Products 22 5.1 Beauty Products 24 5.2 Herbal Health Products 26 6. Crafts and Wild Flowers 29 7. Eco-services 31 7.1 Carbon Sequestration 33 7.2 Eco-tourism 36 8. Traditional Ecological Knowledge 39 9. Wild Greenery and Christmas Trees 41 10. Honey and Honey Products 43 i UNBC Community Development Institute 2009 Future Forest Products and Fibre Use Backgrounder: Non-Timber Forest Resources in the OBAC Region Table of Contents Page Number 11. Wild Edibles 46 11.1 Wild Fruits and Berries 46 11.2 Wild Vegetables and Seasonings 48 11.3 Wild Mushrooms 50 12. Sustainable Landscaping 53 13. General Links for Non-Timber Forest Resources 55 14. References 58 ii UNBC Community Development Institute 2009 Future Forest Products and Fibre Use Backgrounder: Non-Timber Forest Resources in the OBAC Region About this Project The Mountain Pine Beetle infestation has had, and will continue to have, an impact on the timber supply and forest sector in northern British Columbia. -

Big Trees in the Southern Forest Inventory

United States Department of Big Trees in the Southern Agriculture Forest Inventory Forest Service Southern Christopher M. Oswalt, Sonja N. Oswalt, Research Station and Thomas J. Brandeis Research Note SRS–19 March 2010 Abstract or multiple years. Listings of big trees encountered during the most recent forest inventory activities in the South Big trees fascinate people worldwide, inspiring respect, awe, and oftentimes, even controversy. This paper uses a modified version of are reported in this research note and should supplement American Forests’ Big Trees Measuring Guide point system (May 1990) existing lists and registers. to rank trees sampled between January of 1998 and September of 2007 on over 89,000 plots by the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, For more than 75 years, the FIA Program has been charged Forest Inventory and Analysis Program in the Southern United States. Trees were ranked across all States and for each State. There were 1,354,965 by Congress to “make and keep current a comprehensive trees from 12 continental States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands inventory and analysis of the present and prospective sampled. A bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) in Arkansas was the biggest conditions of and requirements for the renewable resources tree (according to the point system) recorded in the South, with a diameter of the forest and rangelands of the United States” of 78.5 inches and a height of 93 feet (total points = 339.615). The tallest tree recorded in the South was a 152-foot tall pecan (Carya illinoinensis) in (McSweeney-McNary Act of May 22, 1928. -

The Effect of Coconut Extract on Callus Growth and Ultrasound Waves On

Folia Forestalia Polonica, Series A – Forestry, 2018, Vol. 60 (4), 261–268 METHODOLOGICAL ARTICLE DOI: 10.2478/ffp-2018-0027 The effect of coconut extract on callus growth and ultrasound waves on production of betulin and betulinic acid in in-vitro culture conditions of Betula pendula Roth species Vahide Payamnoor1 , Razieh Jafari Hajati2, Negar Khodadai1 1 Gorgan University of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources, Faculty of Forest Sciences, Gorgan, Iran, phone: 0098-9113735812, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Shahed University, Traditional Clinical Trial Research Center, Tehran, Iran AbstrAct To determine the effect of coconut extract on callogenesis of Betula pendula, Roth stem barks were cultured in NT (Nagata and Takebe) basic culture media in two individual experiments: i) cultivation explant in different treat- ments of coconut extracts combined with 1 mg l-1 2, 4-D (2, 4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid) and ii) callogenesis in NT media containing 1.5 mg l-1 2,4-D and 0.5 mg l-1 BAP (6-Benzylaminopurine) and then cultivation under the first experiment treatments. The first experiment demonstrated that not all concentrations of coconut extracts lead to callus induction individually, but callus induction increased 84% in a culture containing 5% coconut extract plus 1 mg l-1 2, 4-D. Based on the results of the second experiment, this treatment also significantly increased the wet and dry weights of the produced calluses. The possibility of increasing the betulinic acid and betulin by ultrasound was also studied. Samples cultivated in the selected culture medium were exposed to ultrasound waves in two forms of 1) one exposure and 2) twice exposure (repetition with 24 hr interval) in steps of 20, 60, 100, and 160 sec, and one treatment as the control. -

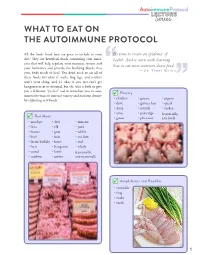

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on Choosing to Connect Your Company and Brand with Consumers’ Interest in Heart Health

HEART-CHECK RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on choosing to connect your company and brand with consumers’ interest in heart health. Together, we can help consumers make heart-smart food and recipe choices. The following information serves as your step-by-step “how- to” program guide and provides all the information you need to navigate the certification process and then begin to leverage the certification of your recipes(s) by using the Heart-Check mark on your website, social media platforms, and in other promotional materials. The iconic Heart-Check mark has been on food packages and in the grocery store since 1995 helping consumers identify foods that can be building blocks of a heart- healthy diet. Now, recipes that meet requirements based on the sound science of the American Heart Association® can also be certified. This offers consumers a bridge from heart-healthy foods to an overall heart-healthy dietary pattern using heart- healthy recipes. Heart-Check certification provides added credibility for your brand, boosts your visibility, and helps your company connect with health-conscious consumers. Seeing the Heart-Check mark on a recipe assures consumers they are making a smart choice. As a program participant, you enjoy these benefits: • INDEPENDENT EVALUATION BY A NUTRITIONAL LEADER. The American Heart Association is one of the nation’s most recognized brands. Consumers seek our guidance on nutrition and heart-healthy living. Certification from the American Heart Association is especially meaningful to consumers because it signifies the independent voice of a trusted health organization. • BOOST YOUR BRAND’S VISIBILITY. -

Harvesting Birch

UAMN Virtual Early Explorers: Water Harvesting Birch Sap A delicious way to explore water in spring! OneTree Alaska is offering two at-home citizen science projects for children in grades K-12 (inquire about younger children). See information below. The “Tapping into Spring” project is providing free birch tapping kits (while supplies last) for families to use at home, through the FNSB School District. The kits are also available to purchase for $25. Instructions and video tutorials are provided. If you are interested, please read the information sheet below, then contact your teacher (K- 12) or Jan Dawe at OneTree Alaska: [email protected]. Photo by Andy Padilla Before all the snow melts, birch trees start producing sap. In the two or three weeks before leaves come out, we can harvest this sweet sap. Watch a video to see how it is done: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sw9JWSum5fs There are two ways you can enjoy birch sap: 1) Drink sap straight from the tree. Birch sap tastes similar to water, with a slightly sweet flavor, and is rich in minerals. 2) Boil the sap slowly to make birch syrup. Birch syrup is tastes great on pancakes, but takes work to produce. If you are ready to try making syrup, contact the staff at OneTree Alaska and they can guide you through the process. Citizen Science Month at Home Be a citizen scientist from the comfort of your own home! OneTree Alaska is offering two projects in honor of Citizen Science Month, each appropriate for students of all ages—plus their families and friends! To participate, let your child’s teacher know of your interest By the end of the day on Monday, April 13, 2020. -

Phytosanitary Measures for Wood Commodities

PHYTOSANITARY MEASURES FOR WOOD COMMODITIES Dr. Andrei Orlinski, EPPO Secretariat Joint UNECE // FAO and WTO Workshop Emerging Trade Measures in Timber Markets Geneva, 2010-03-23 What is EPPO? • Intergovernmental organization • Headquarters in Paris • 50 member countries • 2 Working Parties • More than 20 panels of experts • EPPO website: www.eppo.org EPPO Region Why phytosanitary measures are necessary? • The impact of pests on forests is very important. According to FAO data, at least 35 million hectares of forests worldwide are damaged annually by insect pests only. • The highest risk is caused by introduction and spread of regulated pests with commodities Why phytosanitary measures are necessary? • Some examples of economic and environmental damage: - PWN: in Portugal, almost 24 mln euros spent during 2001 – 2009, in Spain, 344000 euros spent in 2009 and almost 3 mln euros will be spent in 2010, in Japan 10 mln euros are spent annually. - EAB: 16 species of ash could disappear from NA - ALB and CLB: Millions of trees recently killed in NA - DED: almost all elm trees disappeared in Europe Emerald ash borer in Moscow Native range of Fraxinus excelsior R U S S I A in Europe Moscow Asian longhorned beetle Ambrosia beetles Pine wood Nematode Pine wood nematode in Japan Basic principles 1. SOVEREIGNTY 9. COOPERATION 2. NECESSITY 10. EQUIVALENCY 3. MANAGED RISK 11. MODIFICATION 4. MINIMAL IMPACT 5. TRANSPARENCY 6. HARMONIZATION 7. NON DISCRIMINATION 8. TECHNICAL JUSTIFICATION Wood commodities • Non-squared wood • Squared wood • Particle