Tapping – It's Not Just for Maples Anymore Cornell University Seeks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on Choosing to Connect Your Company and Brand with Consumers’ Interest in Heart Health

HEART-CHECK RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on choosing to connect your company and brand with consumers’ interest in heart health. Together, we can help consumers make heart-smart food and recipe choices. The following information serves as your step-by-step “how- to” program guide and provides all the information you need to navigate the certification process and then begin to leverage the certification of your recipes(s) by using the Heart-Check mark on your website, social media platforms, and in other promotional materials. The iconic Heart-Check mark has been on food packages and in the grocery store since 1995 helping consumers identify foods that can be building blocks of a heart- healthy diet. Now, recipes that meet requirements based on the sound science of the American Heart Association® can also be certified. This offers consumers a bridge from heart-healthy foods to an overall heart-healthy dietary pattern using heart- healthy recipes. Heart-Check certification provides added credibility for your brand, boosts your visibility, and helps your company connect with health-conscious consumers. Seeing the Heart-Check mark on a recipe assures consumers they are making a smart choice. As a program participant, you enjoy these benefits: • INDEPENDENT EVALUATION BY A NUTRITIONAL LEADER. The American Heart Association is one of the nation’s most recognized brands. Consumers seek our guidance on nutrition and heart-healthy living. Certification from the American Heart Association is especially meaningful to consumers because it signifies the independent voice of a trusted health organization. • BOOST YOUR BRAND’S VISIBILITY. -

Take Away Menu

HEALTH BAR Smoothies Cold Pessed Juices LOCATIONS POPEYE PUNCH MANGO TANGO GATEWAY PURA VIDA spinach, pineapple, mango, orange, banana, TO GREEN carrot, apple, orange, lemon SOUTH END / CHARLOTTE banana, hemp protein, cayenne, maple syrup, kale, apple, orange, 8.95 704 333 0008 apple juice 9 coconut milk 9 lemon, ginger 8.95 2000 South Blvd. Suite 300 VOLCANO FLYING LUCY EL LUCHADOR TREE OF LIFE orange, lemon, grapefruit, Charlotte NC 28203 spinach, pineapple, banana, banana, peanuts, raw cacao, kale, spinach, parsley, maple syrup, cayenne 8.95 ginger, spirulina, lemonade 9 hemp milk 9 celery, cucumber, lemon, ginger 8.95 POWER CLEANSER SOUTHPARK / CHARLOTTE CHARLIE BROWN CACAO CACAO carrot, cucumber, beet, celery banana, berries, peanut butter, banana, cacao nibs, cacao ALMOND MILK 8.95 704 802 7772 peanuts, apple juice 9 powder, almond milk 9 raw sprouted almonds, coco- 4521 Sharon Rd. Suite 175 nut palm nectar, filtered ZINGER Take Away PINA˜ COLADA OGRE water, vanilla, salt 8.95 beet, apple, orange, lemon, Charlotte NC 28211 pineapple, banana, our cacao cacao smoothie ginger 8.95 coconut milk 9 with a kick of coffee 9 GOLDEN ROOTS carrot, pineapple, turmeric, KALE PEARADISE RALEIGH YOU’RE PINKO DRINKO ginger, lemon 8.95 kale, pear, pineapple, KALE’IN ME orange, berries, banana, acai, cucumber, fennel 8.95 919 324 3515 kale, spinach, cucumber, ginger, lemonade 9 Charter Square Building Menu pineapple, cilantro, kale lemonade 9 GREY HULK Pobiotic Milks 555 Fayetteville St. Suite 100 berries, banana, spirulina, GOLDEN MILK CHOCOLATE -

A La Oils Ebook 2B.Pdf

Table of Contents My Love Affair With Food ............................................................................................ 5 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction to Oils ...................................................................................................... 12 Toasted Pumpkin Seeds .............................................................................................. 20 Sesame & Pumpkin Seed Powder ............................................................................. 21 Mineral Mixture ............................................................................................................ 22 Lemon Kale a la Flax..................................................................................................... 23 Berries a la Kefir........................................................................................................... 24 Toast a la Cultured Veggies ........................................................................................ 25 Cultured Vegetables and/or Kim Chi ....................................................................... 26 Toast a la Coconut Cream & Maple Cream.............................................................. 27 Apple Beet w/ Sesame Powder................................................................................... 28 Buckwheat a la Coconut Cream ................................................................................ -

Honey and Maple Syrup Rules, Regulations, and License Requirements

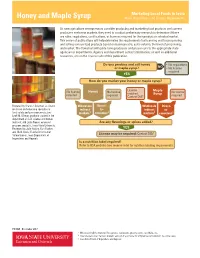

Marketing Local Foods in Iowa Honey and Maple Syrup Rules, Regulations, and License Requirements As new agriculture entrepreneurs consider producing and marketing food products and current producers seek new markets, they need to conduct preliminary research to determine if there are rules, regulations, certifications, or licenses required for their product or selected market. This series of publications will help determine the requirements for licensing and for processing and selling various food products based on business size, sales volume, the level of processing, and market. The flowchart will guide Iowa producers and processors to the appropriate state agencies or departments. Agency and department contact information, as well as additional resources, are on the reverse side of this publication. Do you produce and sell honey • No regulations or maple syrup? NO • No license required YES How do you market your honey or maple syrup? License Maple No license Honey No license No license required required. Syrup required Contact DIA3 required Prepared by Shannon Coleman, assistant Wholesale Direct- Wholesale Direct- professor and extension specialist in indirect to- indirect to- food safety and consumer production; markets1 consumer 2 markets1 consumer 2 Leah M. Gilman, graduate student in the department of food science and human nutrition; and Linda Naeve, extension Are any flavorings or spices added? program specialist, Iowa State University. Reviewed by Julie Kraling, Kurt Rueber, YES and Mark Speltz, Food and Consumer 3 Safety Bureau, Iowa Department of License may be required: Contact DIA Inspections and Appeals. Is a nutrition label required? Refer to FDA website (see reverse side) for nutrition labeling requirements. -

Analysis Fo Sugars in Maple Syrup

APPLICATION NOTE Liquid Chromatography Author: Jamie Foss PerkinElmer, Inc. Shelton, CT Analysis of Sugars in Maple Syrup by Hydrophilic Interaction Introduction Maple syrup is a popular natural Chromatography (HILIC) sweetener that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration defines as the with Refractive Index Detection liquid food derived by concentrating and heat-treating sap from the maple tree.1 Sucrose is the primary sugar found in maple syrup, along with lesser amounts of glucose, fructose and complex carbohydrates.2 Often, the total sugar content of maple syrup is based solely on the amount of sucrose, and does not consider the other sugar sources.2 Maple syrup also contains various other components including minerals, vitamins, amino acids, organic acids, and phytohormones.3 The sugar composition of maple syrup differs from honey, which is dominated by both glucose and fructose, and can contain other sugars such as sucrose and maltose, in much smaller concentrations.3 The analysis of simple sugars is commonly performed using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Often, hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) is used with refractive index (RI) detection owing to the polarity of the sugars, and the lack of a suitable chromophore for UV detection. Therefore, this work describes a simple HILIC-RI method for the analysis of four common sugars found in maple syrup. The structures of these four sugars are shown in Figure 1. Fructose Glucose Sucrose Maltose Figure 1. Chemical structures of the four sugars analyzed in this study. Experimental Table 1. LC Parameters. PerkinElmer Brownlee Analytical Amino, 3 µm, Hardware and Software Column 150 x 4.6 mm (Part# N9303501) Chromatographic separation was achieved using a PerkinElmer LC 300 HPLC system, consisting of an LC 300 10K psi pump and an Solvent A: 75:25 Acetonitrile:Water Solvent Program: Isocratic LC 300 autosampler equipped with an integrated column oven. -

Blueberry Zucchini Muffins 4

Blueberry Muffin Mix Recipes Directions: 1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. 2. Line 2 muffin cavities with parchment liners to prevent sticking. 3. In a small bowl add Blueberry Muffin Mix, baking soda, cinnamon, and a pinch of salt. Blueberry Zucchini Muffins 4. In another small bowl add egg, zucchini, milk, oil, Ingredients: and maple syrup. Combine well. 5. Add wet ingredients into dry and mix until smooth. • 1 packet Blueberry Muffin Mix • 1/8 tsp baking soda 6. Divide batter evenly between the paper liners. • ½ tsp cinnamon 7. Bake for 20 minutes. • Pinch of salt 8. Remove from oven and cool. • ½ beaten egg Tip: Wash, dry and finely grate zucchini, measure before • 1/3 cup zucchini – finely grated, excess water squeezed out squeezing excess water out. • 1 Tbsp milk or half & half • 2 tsp grapeseed oil • 1 Tbsp Ideal Protein Maple Syrup Directions: 1. Preheat oven to 350 degrees. 2. Sift out the blueberries from the muffin mix. 3. Add in baking soda and powder to muffin mix. 4. In a small bowl, add the blueberries and 2 Tbsp of maple syrup, let the berries soak in the syrup for at least 30 minutes. 5. In a small deep bowl beat egg white until soft peaks form, set aside. 6. Mix egg yolk, milk, oil; whisk well. Then add in powder mixture blending until smooth. Blueberry Upside 7. Fold egg white into the smooth batter. Down Cake 8. In the bottom of a small baking dish, spray with nonstick Ingredients: spray and add in blueberries and syrup. • 1 packet Blueberry Muffin Mix 9. -

The Purpose of a Low Fiber, Low Residue Diet Is to Minimize Stool Output

Digestive Health Center Nutrition Services Low Fiber Diet Fiber is a component of complex carbohydrates that the body cannot digest, is found in plant based foods such as beans, lentils, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, etc One of the major functions of fiber is to add bulk to stools and promote regular bowel movements Often, a low fiber diet is then used to reduce stool bulk and output. The diet is used for various medical conditions, such as in ulcerative colitis, during the recovery period after intestinal surgery or to reduce risk of an intestinal obstruction if there is a stricture (narrowing) present in the intestinal tract. A low fiber diet is usually about 10-15 grams of fiber per day Although fiber is not found in meats, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy, it may help to promote overall tolerance to foods if you: Avoid tough and fibrous cuts of meats, poultry, etc. Eat cuts that are soft and tender. Avoid large amounts of dairy if dairy is found to be bothersome (examples- cheese sauces, cream sauces etc). Eat dairy then in small amounts and spread out dairy between all the meals. Avoid any meat, poultry, fish, eggs and dairy made with high fiber ingredients (dried fruits, nuts, seeds, etc) 1 Tips for a Low Fiber Diet: There is always more than one way to eat a specific food. It will help to peel, cook and/or blend your foods with fiber to optimize tolerance and enjoy variety in the diet. Eat small frequent meals throughout the day (4-6 meals/day). -

Dietary Changes to Prevent Calcium Oxalate Stones

Dietary Changes Title To of Prevent article isCalcium VEGETABLES Low Oxalate Medium Oxalate High Oxalate Acorn squash Asparagus Beets - tops, roots, greens Oxalate Stonespositioned here Alfalfa sprouts Artichokes Celery SUB TITLE POSITIONED HERE Cabbage, white Brussels sprouts Collards Cauliflower Broccoli Dandelion greens Cucumbers, peeled Carrots Eggplant reen peas, frozen orn (sweet, white, or yellow) scarole G C E Lettuce, iceberg (1/2 cup) Cucumber (1 medium) Green beans, snap, pod, runner Mung bean sprouts Garlic Kale Pepper, red Green beans, snap, or runner Leeks Turnips, roots beans (high) Okra Zucchini squash Kohlrabi Parsley Lettuce Parsnips butter Peppers, green okeweed iceberg (1 cup) P Mushrooms Popcorn (4 cups, popped) (Orville Food Mg oxalate/100g Mustard greens Redenbacher) Potatoes Onions Potatoes, sweet Rhubarb 600-1235 eppers, green (1/2 medium) umpkin P P Spinach 600-970 Potato chips (50) (Wise Original) Rhubarb Potatoes, white, russet, Idaho Rutabagas Beetroot 870 (1/3 cup) (high) Sorrel Almond 500 Potato salad (1/4 cup) Spinach Tofu 140-280 Radishes Squash, yellow, summer Pecans 202 Snow peas Swiss chard Peanuts 187 Tomato, fresh Tomato sauce, canned Tomato sauce, canned (1/4 cup) Turnip greens Okra 146 Vegetable beef soup Watercress Chocolate 117 (Campbell's) Yams Collard greens 74 Watercress Pesticides Sweet Potato 56 LEGUMES, NUTS, AND SEEDS Low Oxalate Medium Oxalate High Oxalate GRAINS oconut ashews eans, green, waxed, dried C C B Low Oxalate Medium Oxalate High Oxalate Lentils Garbanzo beans, canned (1/4 Baked -

Oatmeal Pancakes Blueberry Syrup

Oatmeal Pancakes & Blueberry Syrup Oatmeal Pancakes Ingredients List 1. Place the oil, Greek yogurt, milk, 1 ¼ cups oats, eggs, 2 tablespoons canola oil or melted, cooled unsalted maple syrup, vanilla, cinnamon, baking powder, and salt in butter or melted, cooled coconut oil a blender. ¾ cup nonfat plain Greek yogurt ½ cup nonfat milk 2. Blend until the batter is smooth, stopping to scrape 2 cups old-fashioned oats divided (or quick oats; do not down the sides of the blender as needed. Continue blending use steel cut or instant) until you don’t see any remaining bits of oats. 2 large eggs 3 tablespoons pure maple syrup 3. Stop the blender, then stir in the remaining ¾ cup oats 1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract and any desired mix-ins. Do not blend again. Let the batter ½ teaspoon ground cinnamon sit for 10 minutes while you heat the skillet/griddle and 1 tablespoon baking powder prep any toppings. ½ teaspoon kosher salt 4. Heat a large nonstick skillet or griddle over medium-low ½ cup mix-ins of choice: toasted chopped nuts heat. Lightly butter or oil the pan if needed (some nonstick chocolate chips, blueberries, or diced fresh or dried pans do not need this). fruit (optional) 5. Once the skillet is hot, drop the batter by ¼ cupfuls into the pan. Let cook gently for 3 to 4 minutes on the first Blueberry Syrup side, until the pancakes look dry at the edges and small bubbles form on top. 1. Mix blueberries, water, and 1 Cup Blueberries sugar together using a 1 Cup Warm Water 6. -

A-08) the Health Effects of High Fructose Syrup (Resolution 407, A-07) (Reference Committee D

REPORT 3 OF THE COUNCIL ON SCIENCE AND PUBLIC HEALTH (A-08) The Health Effects of High Fructose Syrup (Resolution 407, A-07) (Reference Committee D) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Objective: To review the chemical properties and health effects of high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in comparison to other added caloric sweeteners and to evaluate the potential impact of restricting use of fructose-containing sweeteners, including the use of warning labels on foods containing high fructose syrups. Methods: Literature searches for articles published though December 2007 were conducted in the PubMed database and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews using the search terms “high fructose corn syrup” and “high fructose syrup.” Web sites managed by federal and world health agencies, and applicable professional and advocacy organizations, were also reviewed for relevant information. Additional articles were identified by reviewing the reference lists of pertinent publications. Results: HFCS has been increasingly added to foods since its development in the late 1960s. The most commonly used types of HFCS (HFCS-42 and HFCS-55) are similar in composition to sucrose, consisting of roughly equal amounts of fructose and glucose. The primary difference is that these monosaccharides exist free in solution in HFCS, but in disaccharide form in sucrose. The disaccharide sucrose is easily cleaved in the small intestine, so free fructose and glucose are absorbed from both sucrose and HFCS. The advantage to food manufacturers is that the free monosaccharides in HFCS provide better flavor enhancement, stability, freshness, texture, color, pourability, and consistency in foods in comparison to sucrose. Concern about HFCS developed after ecological studies, using per capita estimates of HFCS consumption, found direct correlations between HFCS and obesity. -

Rack of Lamb with Blueberry/Shiraz Sauce Elisabeth J

Volume 5 Article 24 Issue 3 Recipe for Success 12-2011 Rack of Lamb with Blueberry/Shiraz Sauce Elisabeth J. Huff-Lonergan Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/stories Recommended Citation Huff-Lonergan, Elisabeth J. (2011) "Rack of Lamb with Blueberry/Shiraz Sauce," STORIES in Agriculture and Life Sciences: Vol. 5 : Iss. 3 , Article 24. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/stories/vol5/iss3/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in STORIES in Agriculture and Life Sciences by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Huff-Lonergan: Rack of Lamb with Blueberry/Shiraz Sauce From the kitchen of: Elisabeth Huff-Lonergan MS ’91 animal science, PhD ’95, professor animal science Read about Elisabeth at www.ag.iastate.edu/stories Rack of Lamb with Blueberry/Shiraz sauce INGREDIENTS: One rack of lamb 2 tablespoons red onion finely diced 3 cup extra virgin olive oil 2 cups Shiraz wine, 4 tablespoons good quality balsamic vinegar 2 cups low-sodium beef broth 3 cloves garlic, minced or pressed 2 ¼ cups fresh or frozen blueberries 2 teaspoons fresh thyme leaves, or ½ teaspoon 2 tablespoons pure Canadian maple syrup dried oregano 2 cloves garlic, minced or pressed ¼ teaspoon salt 6 sprigs fresh thyme, about 1 tablespoon 8 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper chopped 1 tablespoon Dijon mustard 2-inch sprig fresh rosemary leaves, 12 3-inch sprigs fresh rosemary leaves only 2 teaspoons olive oil Pepper DIRECTIONS: Prepare marinade by combining first eight ingredients in a small bowl or glass measuring cup and whisking until incorporated.