A-08) the Health Effects of High Fructose Syrup (Resolution 407, A-07) (Reference Committee D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

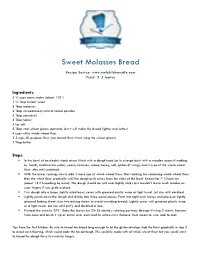

Sweet Molasses Bread Recipe Source: Yield: 2-3 Loaves

Sweet Molasses Bread Recipe Source: www.melskitchencafe.com Yield: 2-3 loaves Ingredients: 2 ½ cups warm water (about 110°) 1 ½ Tbsp instant yeast 5 Tbsp molasses 2 Tbsp unsweetened, natural cocoa powder 3 Tbsp canola oil 5 Tbsp honey 2 tsp salt 3 Tbsp vital wheat gluten (optional, but it will make the bread lighter and softer) 4 cups white whole wheat flour 2-3 cups all-purpose flour (use bread flour if not using the wheat gluten) 1 Tbsp butter Steps: . In the bowl of an electric stand mixer fitted with a dough hook (or in a large bowl with a wooden spoon if making by hand), combine the water, yeast, molasses, cocoa, honey, salt, gluten (if using), and 2 cups of the whole wheat flour. Mix until combined. With the mixer running, slowly add 1 more cup of whole wheat flour. Start adding the remaining whole wheat flour then the white flour gradually until the dough pulls away from the sides of the bowl. Knead for 7-10 minutes (about 15 if kneading by hand). The dough should be soft and slightly tacky but shouldn’t leave much residue on your fingers if you grab a piece. Turn dough into a large, lightly oiled bowl, cover with greased plastic wrap or light towel. Let rise until doubled. Lightly punch down the dough and divide into three equal pieces. Form into tight oval loaves and place on lightly greased baking sheets (use two baking sheets to avoid crowding bread). Lightly cover with greased plastic wrap or a light towel. -

Carbohydrates Carbohydrates Are One of the Main Macronutrients

Carbohydrates Carbohydrates are one of the main macronutrients. They provide an essential source of energy. They are mainly found in plants, where they are manufactured by photosynthesis. Photosynthesis Photosynthesis is the process by which green plants use sunlight to make sugar (glucose) from carbon dioxide and water. How photosynthesis occurs Plant roots absorb water (H2O) from the soil. Leaves take in carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air. Chlorophyll (green pigment) in leaves absorbs energy from the sun. Result Glucose (sugar) (C6H12O6) is formed. Oxygen (O2) is released into the air. Equation for photosynthesis light energy 6CO2 + 6H2O — C6H12O6 + 6O2 chlorophyll Carbon + dioxide water — glucose + oxygen Elemental composition of carbohydrates Carbohydrates are made up of three elements: carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O). Monosaccharides Structure Chemical formula Examples Sources A simple sugar that C6H12O6 Glucose Fruit contains one simple Fructose Fruit and honey sugar unit. It is the Galactose Digested milk smallest unit of a carbohydrate. Chemical structure Disaccharides Structure Chemical formula Examples Sources Formed when two C12H22O11 Maltose Barley monosaccharides (glucose + glucose) Table sugar join, resulting in the Sucrose Milk loss of a water (H2O) (glucose + fructose) molecule Lactose (condensation (glucose + galactose) reaction). Chemical structure Polysaccharides Structure Chemical formula Examples Sources Formed when three (C6H10O5)n Starch Cereals and potatoes or more (n refers to the Pectin Fruit monosaccharides join number of Glycogen Meat together, resulting in monosaccharides Gums Plants and seaweed the loss of a water joined together) Cellulose Skins of fruit and (H2O) molecule with (dietary fibre) vegetables each new link Nuts (condensation reaction). Chains can be straight or branched. -

Pentose PO4 Pathway, Fructose, Galactose Metabolism.Pptx

Pentose PO4 pathway, Fructose, galactose metabolism The Entner Doudoroff pathway begins with hexokinase producing Glucose 6 PO4 , but produce only one ATP. This pathway prevalent in anaerobes such as Pseudomonas, they doe not have a Phosphofructokinase. The pentose phosphate pathway (also called the phosphogluconate pathway and the hexose monophosphate shunt) is a biochemical pathway parallel to glycolysis that generates NADPH and pentoses. While it does involve oxidation of glucose, its primary role is anabolic rather than catabolic. There are two distinct phases in the pathway. The first is the oxidative phase, in which NADPH is generated, and the second is the non-oxidative synthesis of 5-carbon sugars. For most organisms, the pentose phosphate pathway takes place in the cytosol. For each mole of glucose 6 PO4 metabolized to ribulose 5 PO4, 2 moles of NADPH are produced. 6-Phosphogluconate dh is not only an oxidation step but it’s also a decarboxylation reaction. The primary results of the pathway are: The generation of reducing equivalents, in the form of NADPH, used in reductive biosynthesis reactions within cells (e.g. fatty acid synthesis). Production of ribose-5-phosphate (R5P), used in the synthesis of nucleotides and nucleic acids. Production of erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P), used in the synthesis of aromatic amino acids. Transketolase and transaldolase reactions are similar in that they transfer between carbon chains, transketolases 2 carbon units or transaldolases 3 carbon units. Regulation; Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is the rate- controlling enzyme of this pathway. It is allosterically stimulated by NADP+. The ratio of NADPH:NADP+ is normally about 100:1 in liver cytosol. -

Metabolism of Monosaccharides and Disaccharides Glucose Is the Most Common Monosaccharide Consumed by Humans

Metabolism of Monosaccharides and disaccharides Glucose is the most common monosaccharide consumed by humans. Two other monosaccharides that occur in significant amounts in the diet are fructose and galactose. Galactose is an important component of cell structural carbohydrates. Catabolism of fructose and galactose are essential pathways of energy metabolism in the body (both illustrated with blue in the adjacent diagram). About 15-20% of calories in the diet are supplied by fructose (55 g/day). The major source of fructose is the disaccharide sucrose. Entry of fructose is not dependent on insulin. Galactose is an important component Of cell structural carbohydrates. Fructose needs to be phosphorylated to enter the pathway either by hexokinase or fructokinase. Hexokinase has low affinity towards fructose (high Km) therefore unless high concentrations of fructose exist very little fructose will be converted to Fructose 6-P. Fructokinase provides the main mechanism of phosphorylation to fructose 1-P, Fructose 1-P does not convert to Fructose 1,6 bisphosphate but is metabolized to Glyceraldehyde and DHAP by aldolase B. DHAP can enter glycolysis or gluconeogenesis while Glyceraldehyde can be metabolized by a number of pathways. The rate of fructose metabolism is more rapid than that of glucose because trioses formed from fructose 1-phosphate bypass PFK1, the rate limiting step in glycolisis. What disorders are associated with fructose metabolism? Where? First lets summarize the various routes of Fructose metabolism in the diagram. Disorders of fructose metabolism can result from excessive fructose consumption. An increase in fructose 1-P due to rapid phosphorylation. This accumulation leads to sequestering of phosphate (A & B). -

Relationships Among Impurity Components, Sucrose, and Sugarbeet Processing Quality

2 Journal of Sugar Beet Research Vol. 52 Nos. 1 & 2 Relationships Among Impurity Components, Sucrose, and Sugarbeet Processing Quality L. G. Campbell and K.K. Fugate USDA-ARS Northern Crop Science Laboratory, Fargo, ND 58102-2765 Corresponding author: Larry Campbell ([email protected]) DOI: 10.5274/jsbr.52.1.2 ABSTRACT Sodium, potassium, amino-nitrogen, and invert sugar are nat- urally-occurring constituents of the sugarbeet root, referred to as impurities, which impede sucrose extraction during rou- tine factory operations. Three germplasm lines selected for low sodium, potassium, or amino-nitrogen and a line selected for high amino-nitrogen concentration from the same parental population and two lines selected from another source, one for high and the other for low amino-nitrogen concentration, were the basis for examining relationships among the impurity components and between the impurity components and sucrose concentration, sucrose loss to mo- lasses, and sucrose extraction rate. Concentrations of the three impurity components were altered through selection; however, in no case did this result in a consistent significant increase in sucrose concentration or estimates of the propor- tion of the sucrose that would be extracted. Correlation analyses indicated a larger role for sodium than for potas- sium or amino-nitrogen in determining relative sucrose con- centration. Selection for low sodium concentration, however, did not increase the percent extractable sucrose, relative to the parental population. The probability of significant im- provement in the processing quality of elite germplasm by re- ducing the concentration of individual impurity components appears to be low, based upon the populations examined in this study. -

Field Guide to Common Macrofungi in Eastern Forests and Their Ecosystem Functions

United States Department of Field Guide to Agriculture Common Macrofungi Forest Service in Eastern Forests Northern Research Station and Their Ecosystem General Technical Report NRS-79 Functions Michael E. Ostry Neil A. Anderson Joseph G. O’Brien Cover Photos Front: Morel, Morchella esculenta. Photo by Neil A. Anderson, University of Minnesota. Back: Bear’s Head Tooth, Hericium coralloides. Photo by Michael E. Ostry, U.S. Forest Service. The Authors MICHAEL E. OSTRY, research plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, St. Paul, MN NEIL A. ANDERSON, professor emeritus, University of Minnesota, Department of Plant Pathology, St. Paul, MN JOSEPH G. O’BRIEN, plant pathologist, U.S. Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, St. Paul, MN Manuscript received for publication 23 April 2010 Published by: For additional copies: U.S. FOREST SERVICE U.S. Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 April 2011 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.nrs.fs.fed.us/ CONTENTS Introduction: About this Guide 1 Mushroom Basics 2 Aspen-Birch Ecosystem Mycorrhizal On the ground associated with tree roots Fly Agaric Amanita muscaria 8 Destroying Angel Amanita virosa, A. verna, A. bisporigera 9 The Omnipresent Laccaria Laccaria bicolor 10 Aspen Bolete Leccinum aurantiacum, L. insigne 11 Birch Bolete Leccinum scabrum 12 Saprophytic Litter and Wood Decay On wood Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus populinus (P. ostreatus) 13 Artist’s Conk Ganoderma applanatum -

Florida Blueberry Pollination Factsheet

Florida Blueberry PROJECT ICP Pollination Blueberries Require Pollination Blueberries need to be cross-pollinated with another cultivar of the same species (rabbiteye or southern highbush blueberry) in order to produce fruit. Cross-pollination allows for better fruit set, berry size, and earlier ripening. Most growers bring in managed European honey bee hives or commercial bumble bees for pollination. Several types of wild bees are also effective and abundant pollinators of Florida blueberries. All of these different kinds of bees visit blueberry flowers to collect pollen and nectar to feed their young. Integrated Crop Pollination: combining strategies to improve pollination Having many different species of pollinators can help ensure reliable pollination. Different species of bees tend to visit flowers at different times of the day and are active at different times throughout the bloom season; having a diverse set of bees active in your fields can ensure consistent pollination from the beginning to the end of crop bloom. Honey bee abundance and wild bee diversity are both important contributors to southeastern US blueberry pollination. Cool, rainy, and windy spring weather can lead to poor pollination. When multiple pollinator species are active, more flowers are likely to be visited on poor weather days. Large-bodied bees, including all three types of wild bees that visit Florida blueberry flowers, stay more active under Pollination is essential for blueberry production. On the left, a blueberry cluster that was enclosed in a mesh bag during cool and cloudy conditions than do honey bees and can help bloom to exclude pollinators. On the right, a blueberry cluster pollinate the crop in variable spring weather. -

Delicioussm GOLDEN BROWN SUGAR Product Information Sheet

9501 Southview Ave. Brookfield, Illinois 60513 www.sweetenersupply.com www.powderedcellulose.com DELICIOUSsm GOLDEN BROWN SUGAR Product Information Sheet Product Code BR0050 A brown sugar produced by enrobing cane granulated sugar with high quality cane juice molasses. Delicious Golden brown is perfect for baked goods, barbecue sauces, or any formulation where a quality brown sugar is desired. Label Declaration: Brown Sugar (Sugar, Molasses) ANALYSIS Dry Solids 98% min Moisture 2% max Ash 2% max. Color Golden Brown Odor Typical of Brown Sugar Sucrose 90% typical Invert 4% typical NUTRITIONAL ANALYSIS Per 100 g Calories 390 Moisture 2g Carbohydrate 97.6 Sugars 97.6 Ash 0.40 Sodium 17 mg Potassium 96 mg Magnesium 9 mg Calcium 25 mg Not a dietary significant source of protein, fat, vitamins or fiber. MICROBIOLOGY Aerobic Plate Count – Max 500 cfu/g Yeast & Mold – Max 100 cfu/g Pathogen free Phone (708) 588-8400 Fax (708) 588-8460 Revision 3 3/21/16 approved VP Food Tech 9501 Southview Ave. Brookfield, Illinois 60513 www.sweetenersupply.com www.powderedcellulose.com Allergen Statement Brown Sugar Allergen Source: Present in Used on same Comments: Product production line Dairy: No No Egg/Egg Derivative: No No Soy/Soy Derivative: No No Peanut: No No Wheat/Wheat No No Derivative: Fish (Cod, tuna, No No etc): Nuts (tree nuts, No No etc): Crustaceans (shell No No fish, lobster, etc.): Mollusks (snail, No No clams, etc.): Seeds (sesame, No No celery, etc.): Gluten: No No Colors (FD&C, No No Caramel color): MSG: No No Sorbates: No No Sulfites: No No Benzoates: No No BHA/BHT: No No Artificial No No Sweeteners: Animal derivatives: No No Mustard No No Phone (708) 588-8400 Fax (708) 588-8460 Revision 3 3/21/16 approved VP Food Tech 9501 Southview Ave. -

Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Handout

HEALTH INDICATOR 13: HEALTH INDICATOR 1:SUGAR-SWEETENED INDIVIDUALS BELOW BEVERAGE 200% FEDERAL CONSUMPTION POVERTY LEVEL (FPL) DESIRED RESULT: REDUCE OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY DESIRED RESULT: DECREASE THE NUMBER OF PEOPLE LIVING IN POVERTY Rationale for Selection: CURRENT TARGET Rationale for Selection: Obesity continues to be a concern in North Carolina. Sugar-sweetened 33.6%CURRENT 17.0%TARGET (Youth-2017) (Youth) beveragesIncome (SSB) level are the is aleading strong source predictor of calories of a andperson’s added access sugars toin 36.8% 27% the Americanresources diet. and health status. Low income restricts access to 34.2%(2013-17) 20.0% (Adults-2017) (Adults) quality housing, transportation, food, and education, which Context F, G Obesity islimits one of the opportunities largest contributors tofor morbidity people and mortality to live healthy lives. DEFINITION DEFINITION 102 Percent of youth and adults reporting in the United States, for both youth and adults. Across all ages, the “Sugar-sweetened Percent of individuals with incomes at or consumption of one or more sugar- rates of obesity continue to rise. For years, efforts to reduce overweight beverages (SSBs) are below 200% of the FPL sweetened beverages (SSBs) per day and obesityContext have largely been focused on physical activity and healthy the leading dietary eating (e.g., fruit and vegetable intake). New efforts are also targeting Poverty is directly linked to negative health outcomes. Income is centralsource to ofaccessing added resources sugar DETAILSDETAILS sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, which is directly linked Not applicable needed to be healthy such as safe housing, nutritious food, education, and transportation,103 Youth (high school students) and adults to obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and dental problems.103 for Americans. -

What to Eat on the Autoimmune Protocol

WHAT TO EAT ON THE AUTOIMMUNE PROTOCOL All the foods listed here are great to include in your It’s time to create an epidemic of - health. And it starts with learning ents that will help regulate your immune system and how to eat more nutrient-dense food. your hormones and provide the building blocks that your body needs to heal. You don’t need to eat all of these foods (it’s okay if snails, frog legs, and crickets aren’t your thing, and it’s okay if you just can’t get kangaroo meat or mizuna), but the idea is both to give Poultry innovative ways to increase variety and nutrient density • chicken • grouse • pigeon by exploring new foods. • dove • guinea hen • quail • duck • ostrich • turkey • emu • partridge (essentially, Red Meat • goose • pheasant any bird) • antelope • deer • mutton • bear • elk • pork • beaver • goat • rabbit • beef • hare • sea lion • • horse • seal • boar • kangaroo • whale • camel • lamb (essentially, • caribou • moose any mammal) Amphibians and Reptiles • crocodile • frog • snake • turtle 1 22 Fish* Shellfish • anchovy • gar • • abalone • limpet • scallop • Arctic char • haddock • salmon • clam • lobster • shrimp • Atlantic • hake • sardine • cockle • mussel • snail croaker • halibut • shad • conch • octopus • squid • barcheek • herring • shark • crab • oyster • whelk goby • John Dory • sheepshead • • periwinkle • bass • king • silverside • • prawn • bonito mackerel • smelt • bream • lamprey • snakehead • brill • ling • snapper • brisling • loach • sole • carp • mackerel • • • mahi mahi • tarpon • cod • marlin • tilapia • common dab • • • conger • minnow • trout • crappie • • tub gurnard • croaker • mullet • tuna • drum • pandora • turbot Other Seafood • eel • perch • walleye • anemone • sea squirt • fera • plaice • whiting • caviar/roe • sea urchin • • pollock • • *See page 387 for Selenium Health Benet Values. -

RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on Choosing to Connect Your Company and Brand with Consumers’ Interest in Heart Health

HEART-CHECK RECIPE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM GUIDE MAY 2019 WELCOME! Congratulations on choosing to connect your company and brand with consumers’ interest in heart health. Together, we can help consumers make heart-smart food and recipe choices. The following information serves as your step-by-step “how- to” program guide and provides all the information you need to navigate the certification process and then begin to leverage the certification of your recipes(s) by using the Heart-Check mark on your website, social media platforms, and in other promotional materials. The iconic Heart-Check mark has been on food packages and in the grocery store since 1995 helping consumers identify foods that can be building blocks of a heart- healthy diet. Now, recipes that meet requirements based on the sound science of the American Heart Association® can also be certified. This offers consumers a bridge from heart-healthy foods to an overall heart-healthy dietary pattern using heart- healthy recipes. Heart-Check certification provides added credibility for your brand, boosts your visibility, and helps your company connect with health-conscious consumers. Seeing the Heart-Check mark on a recipe assures consumers they are making a smart choice. As a program participant, you enjoy these benefits: • INDEPENDENT EVALUATION BY A NUTRITIONAL LEADER. The American Heart Association is one of the nation’s most recognized brands. Consumers seek our guidance on nutrition and heart-healthy living. Certification from the American Heart Association is especially meaningful to consumers because it signifies the independent voice of a trusted health organization. • BOOST YOUR BRAND’S VISIBILITY. -

The Toxic Truth About Sugar Added Sweeteners Pose Dangers to Health That Justify Controlling Them Like Alcohol, Argue Robert H

COMMENT ECOLOGY How elephants NEUROSCIENCE The LITERATURE How Charles OBITUARY Philip Lawley and the could reduce fire risk in source of the self in Dickens drew on science, but discovery that DNA damage Australia p.30 the brain’s wiring p.31 left room for wonder p.32 can cause cancer p.36 ILLUSTRATION BY MARK SMITH BY ILLUSTRATION The toxic truth about sugar Added sweeteners pose dangers to health that justify controlling them like alcohol, argue Robert H. Lustig, Laura A. Schmidt and Claire D. Brindis. ast September, the United Nations will have a normal lifespan. Conversely, up declared that, for the first time in SUMMARY to 40% of normal-weight people develop human history, chronic non-commu- ● Sugar consumption is linked to a rise the diseases that constitute the metabolic Lnicable diseases such as heart disease, cancer in non-communicable disease syndrome: diabetes, hypertension, lipid and diabetes pose a greater health burden ● Sugar’s effects on the body can be problems, cardiovascular disease and worldwide than do infectious diseases, similar to those of alcohol non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Obesity contributing to 35 million deaths annually. ● Regulation could include tax, limiting is not the cause; rather, it is a marker for This is not just a problem of the developed sales during school hours and placing metabolic dysfunction, which is even more world. Every country that has adopted the age limits on purchase prevalent. Western diet — one dominated by low-cost, The UN announcement targets tobacco, highly processed food — has witnessed rising alcohol and diet as the central risk factors rates of obesity and related diseases.