Cooperatives in the U.S.-Citrus Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kettleman City, Kings County Please Read Immediately

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE OFFICIAL NOTICE FOR CITY OF KETTLEMAN CITY, KINGS COUNTY PLEASE READ IMMEDIATELY THE NOTICE OF TREATMENT FOR THE ASIAN CITRUS PSYLLID On September 18, 2020 the California Department of Food and Agriculture (CDFA) confirmed the presence of Asian citrus psyllid (ACP), Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, a harmful exotic pest in the city of Kettleman City, Kings County. This detection indicate that a breeding population exists in the area. The devastating citrus disease Huanglongbing (HLB) is spread by the feeding action of ACP. The ACP infestation is sufficiently isolated and localized to be amenable to the CDFA’s ACP treatment work plan. A Program Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) has been certified which analyzes the ACP treatment program in accordance with Public Resources Code, Sections 21000 et seq. The PEIR is available at http://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/peir/. The treatment activities described below are consistent with the PEIR. In accordance with integrated pest management principles, CDFA has evaluated possible treatment methods and determined that there are no physical, cultural, or biological control methods available to eliminate the ACP from this area. Notice of Treatment is valid until September 18, 2021, which is the amount of time necessary to determine that the treatment was successful. The treatment plan for the ACP infestation will be implemented within a 50-meter radius of each detection site, as follows: • Tempo® SC Ultra (cyfluthrin), a contact insecticide for controlling the adults and nymphs of ACP, will be applied from the ground using hydraulic spray equipment to the foliage of host plants; and • Merit® 2F or CoreTect™ (imidacloprid), a systemic insecticide for controlling the immature life stages of ACP, will be applied to the soil underneath host plants. -

Survey of Phenolic Compounds Produced in Citrus

USDA ??:-Z7 S rveyof Phenolic United States Department of Agriculture C mpounds Produced IliIIiI Agricultural Research In Citrus Service Technical Bulletin Number 1856 December 1998 United States Department of Agriculture Survey of Phenolic Compounds Agricultural Produced in Citrus Research Service Mark Berhow, Brent Tisserat, Katherine Kanes, and Carl Vandercook Technical Bulletin Number 1856 December 1998 This research project was conducted at USDA, Agricultural Research Service, Fruit and Vegetable Chem istry laboratory, Pasadena, California, where Berhow was a research chemist, TIsserat was a research geneticist, Kanes was a research associate, and Vandercook, now retired, was a research chemist. Berhow and Tisserat now work at the USDA-ARS National Center for AgriCUltural Utilization Research, Peoria, Illinois, where Berhow is a research chemist and Tisserat is a research geneticist. Abstract Berhow, M., B. Tisserat, K. Kanes, and C. Vandercook. 1998. Survey of Mention of trade names or companies in this publication is solely for the Phenolic Compounds Produced in Citrus. U.S. Department ofAgriculture, purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommenda Agricultural Research Service, Technical Bulletin No. 1856, 158 pp. tion or endorsement by the U. S. Department ofAgriculture over others not mentioned. A survey of phenolic compounds, especially flavanones and flavone and flavonol compounds, using high pressure liquid chromatography was While supplies last, single copies of this publication may be obtained at no performed in Rutaceae, subfamily Aurantioideae, representing 5 genera, cost from- 35 species, and 114 cultivars. The average number of peaks, or phenolic USDA, ARS, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research compounds, occurring in citrus leaf, flavedo, albedo, and juice vesicles 1815 North University Street were 21, 17, 15, and 9.3, respectively. -

Citrus Industry Biosecurity Plan 2015

Industry Biosecurity Plan for the Citrus Industry Version 3.0 July 2015 PLANT HEALTH AUSTRALIA | Citrus Industry Biosecurity Plan 2015 Location: Level 1 1 Phipps Close DEAKIN ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6215 7700 Fax: +61 2 6260 4321 E-mail: [email protected] Visit our web site: www.planthealthaustralia.com.au An electronic copy of this plan is available through the email address listed above. © Plant Health Australia Limited 2004 Copyright in this publication is owned by Plant Health Australia Limited, except when content has been provided by other contributors, in which case copyright may be owned by another person. With the exception of any material protected by a trade mark, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivs 3.0 Australia licence. Any use of this publication, other than as authorised under this licence or copyright law, is prohibited. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/3.0/ - This details the relevant licence conditions, including the full legal code. This licence allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to Plant Health Australia (as below). In referencing this document, the preferred citation is: Plant Health Australia Ltd (2004) Industry Biosecurity Plan for the Citrus Industry (Version 3.0 – July 2015). Plant Health Australia, Canberra, ACT. Disclaimer: The material contained in this publication is produced for general information only. It is not intended as professional advice on any particular matter. No person should act or fail to act on the basis of any material contained in this publication without first obtaining specific and independent professional advice. -

Improvement of Subtropical Fruit Crops: Citrus

IMPROVEMENT OF SUBTROPICAL FRUIT CROPS: CITRUS HAMILTON P. ÏRAUB, Senior Iloriiciilturist T. RALPH ROBCNSON, Senior Physiolo- gist Division of Frnil and Vegetable Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Tndusiry MORE than half of the 13 fruit crops known to have been cultivated longer than 4,000 years,according to the researches of DeCandolle (7)\ are tropical and subtropical fruits—mango, oliv^e, fig, date, banana, jujube, and pomegranate. The citrus fruits as a group, the lychee, and the persimmon have been cultivated for thousands of years in the Orient; the avocado and papaya were important food crops in the American Tropics and subtropics long before the discovery of the New World. Other types, such as the pineapple, granadilla, cherimoya, jaboticaba, etc., are of more recent introduction, and some of these have not received the attention of the plant breeder to any appreciable extent. Through the centuries preceding recorded history and up to recent times, progress in the improvement of most subtropical fruits was accomplished by the trial-error method, which is crude and usually expensive if measured by modern standards. With the general accept- ance of the Mendelian principles of heredity—unit characters, domi- nance, and segregation—early in the twentieth century a starting point was provided for the development of a truly modern science of genetics. In this article it is the purpose to consider how subtropical citrus fruit crops have been improved, are now being improved, or are likel3^ to be improved by scientific breeding. Each of the more important crops will be considered more or less in detail. -

AUSTRALIAN CITRUS TREE CENSUS 2014 Survey Scope 1,750 Businesses Contacted 1,064 Businesses in Report*

AUSTRALIAN CITRUS TREE CENSUS 2014 Survey Scope 1,750 businesses contacted 1,064 businesses in report* *It is estimated that an additional 2,500 hectares are not represented in this report. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The following personnel and agencies are INTRODUCTION acknowledged for their input and assistance in collecting data for the 2014 Citrus Tree Census. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries The Australian citrus industry is one of Australia’s largest Andrew Creek, Development Officer – Citrus horticulture industries, with commercial production in five States Tammy Galvin, Senior Land Services Officer (Projects) and one territory. Department of Agriculture and Food Western Australia It is one of Australia’s largest fresh produce exporters, exporting on average 160,000 tonnes Bronwyn Walsh, Value Chain Coordinator – Citrus per year, over the last ten years. While the industry’s size and output is significant in Australia, it comprises less than 0.5% of global production and is one of the highest cost producers in the Citrus Australia South Australia Region world, relying on its reputation for quality and safety to command premium prices in high paying Mark Doecke, Committee Member export markets. Anthony Fulwood, Committee Member The Citrus Tree Census is an online database developed by Citrus Australia to collect national Penny Smith Committee Member production statistics about variety, rootstock, tree age and hectares planted. This information is essential for: This project has been funded by Horticulture Innovation Australia Limited using the citrus industry levy and funds • Guiding growers when choosing which varieties to plant from the Australian Government. • Assisting the citrus supply chain with packing and logistics investment decisions and • Directing market development and research and development needs. -

Physiology of Citrus Fruiting

REVIEW Physiology of citrus fruiting Domingo J. Iglesias, Manuel Cercós, José M. Colmenero-Flores, Miguel A. Naranjo, Gabino Ríos, Esther Carrera, Omar Ruiz-Rivero, Ignacio Lliso, Raphael Morillon1, Francisco R. Tadeo and Manuel Talon* Centro de Genómica, Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Agrarias, Apdo. Oficial, 46113 Moncada, Valencia, Spain. 1Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Dévelopement (CIRAD), San Giuliano (Corse), F-20230, France. *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 31 October 2007; Accepted: 02 November 2007 Citrus is the main fruit tree crop in the world and therefore has a tremendous economical, social and cultural impact in our society. In recent years, our knowledge on plant reproductive biology has increased considerably mostly because of the work developed in model plants. However, the information generated in these species cannot always be applied to citrus, predominantly because citrus is a perennial tree crop that exhibits a very peculiar and unusual reproductive biology. Regulation of fruit growth and development in citrus is an intricate phenomenon depending upon many internal and external factors that may operate both sequentially and simultaneously. The elements and mechanisms whereby endogenous and environmental stimuli affect fruit growth are being interpreted and this knowledge may help to provide tools that allow optimizing production and fruit with enhanced nutritional value, the ultimate goal of the Citrus Industry. This article will review the progress that has taken place in the physiology of citrus fruiting during recent years and present the current status of major research topics in this area. Key words: abiotic stresses, abscission, color break, flowering, fruit set, ripening Fisiologia da frutificação em citrus. -

A Historical Note on Two Unreported Obstacles for Cross-Protecting Mature Citrus Trees Against Severe Citrus Tristeza Virus Isolates

Letter to the Editor A historical note on two unreported obstacles for cross-protecting mature citrus trees against severe Citrus tristeza virus isolates. M Bar-Joseph1* 1 The S Tolkowsky Laboratory, ARO, The Volcani Center, Bet Dagan 50250, Israel. *Correspondence to: [email protected] Citation: Bar-Joseph M. 2015. A historical note on two unreported obstacles for cross-protecting mature citrus trees against severe Citrus tristeza virus isolates. J Cit Pathol. iocv_journalcitruspathology_28534. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ During the years 1970 to 1986 the Israeli citrus experiment to prevent decline was established in a mature industry had undertaken a costly and ambitious program (around 20 years old) Valencia orange grove grafted on for suppressing the outbreak of a Citrus tristeza virus sour orange. The experimental plot was part of the Yachin (CTV) epidemic. For comprehensive reviews of CTV and Company Morasha plantation located east of Tel Aviv. In the tristeza disease see Dawson et al. (2013), Moreno et this area an extremely severe isolate Mor-T (Ben-Zeev et al. (2008), and Bar-Joseph et al. (1989). The program, al. 1988), belonging to the VT strain (Mawassi et al. which involved millions of ELISA tests, was a 1993; Shalitin et al. 1994) was causing rapid decline of coordinated effort of virus research, extension, and Minneola tangelo, Valencia, and Shamouti orange trees at regulatory agencies funded by the local citrus marketing early stages of natural infection. Trees of sensitive board and the Ministry of Agriculture. These major combinations infected by Mor-T were showing quick commitments of CTV control by a “search and destroy” decline long before the virions pervaded the canopies to strategy were based on statistical analyses indicating that allow routine detection by ELISA (Ben-Zeev et al. -

Our Citrus Heritage

This is a republication of an article which first appeared in the November/December 2002 issue of Garden Compass Magazine California’s Second Great Gold Rush: Our Citrus Heritage It was said that while by Tom Spellman driving through Southern During the late 1760s, before the United States California during the 1930s became a country, the Spanish padres moved and 1940s, you could smell the orange blossoms for north from Mexico into that vast expanse of 100 miles. mountains and valleys known as Alta California. Their intent was to establish a chain of missions, approximately a day’s ride between one another, By 1875, citrus growers were paying $5 per bud for navel orange and settle this new region. propagation material. One of the first challenges the padres faced was The Washington navel orange is finding a reliable source of produce. They had lots still one of the most popular fruits in the world and is considered by of native game and fowl, and each mission was many to be the foundation of the constructed close to a permanent freshwater source. But native fruits and vegetables were California citrus industry. almost non-existent. To survive, immense gardens of vegetables, tree fruits and grapes Amazingly, one of the two original were planted. parent navel orange trees still survives today in downtown The padres brought with them the precious seeds for the Spanish sweet orange—a thin- Riverside and is a registered skinned, seedy fruit similar to the Valencia orange—and a thick-skinned citron-type lemon. historical landmark. Both were completely unknown to the area. -

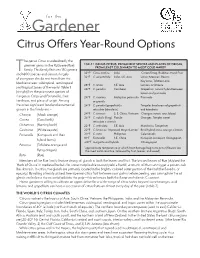

Citrus Offers Year-Round Options

for the Gardener Citrus Offers Year-Round Options he genus Citrus is undoubtedly the premier genus in the Rutaceae (Rue) TABLE 1. GENUS CITRUS: PROMINENT SPECIES AND PLACES OF ORIGIN, FROM LEAST COLD HARDY TO MOST COLD HARDY family. This family features 150 genera T 32ºF* Citrus medica India Citron/Etrog, Buddha’s Hand Fruit and 1600 species and consists largely 32ºF C. aurantiifolia India, S.E. Asia Limes: Mexican, Bearss, of evergreen shrubs and trees from the Key Lime, Tahitian Lime Mediterranean, subtropical, semitropical 28ºF C. limon S.E. Asia Lemons or limonia and tropical zones of the world. Table 1 26ºF C. paradisi Carribean Grapefruit: natural hybrid between (at right) lists the prominent species of lemon and pummelo the genus Citrus (and Fortunella), their 24ºF C. maxima Malaysian peninsula Pummelo hardiness, and place of origin. Among or grandis the other significant food and ornamental 24ºF C. paradisi (grapefruit) x Tangelo: bred cross of grapefruit genera in the family are – reticulata (Mandarin) and Mandarin Choisya (Mock orange) 24ºF C. sinensis S. E. China, Vietnam Oranges: sweet, sour, blood 24ºF C. nobilis (King) Florida Oranges: Temple, sweet Correa (Coral bells) reticulata x sinensis Dictamnus (Burning bush) 22ºF C. reticulata S.E. Asia Mandarins, Tangerines Casimiroa (White zapote) 22ºF C. limon cv. ‘Improved Meyer Lemon’ Bred hybrid cross, orange x lemon Fortunella (Kumquats and their 20ºF C. mitis Phillipines Calamondin 18ºF Fortunella S.E. China Kumquat, Limequat, Orangequat, hybrid forms) -20ºF margarita and hybrids Citrangequat Poncirus (Trifoliate orange and * approximate temperature at which frost damage begins to occur (flowers are flying dragon) the most cold-sensitive, followed by fruit, leaves, and wood) Ruta (Rue) Members of the Rue family feature strong oil glands in both the leaves and fruit. -

New Disease-Resistant Rootstocks Urgently Neededby Citrus Growers

FLORIDA STATE HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 201 20 years of age before they bloomed in North recent plantings of this Rhodesian mahogany ern Rhodesia, Africa. in southern and south central parts of Florida The mother mahogany tree in Miami, which show that young seedlings of this species have is approximately 20 years old, probably came survived frosts, hurricanes, and dry weather from one of Dr. W. L. Thompson's numerous when planted in hammocks, but have not been introductions of Khaya nyasica seed from Mt. able to fare for themselves under exposed Silinda, Southern Rhodesia, the earliest intro conditions in the open. If these trees can sur duction being received in 1902 (1). This tree vive and reproduce themselves under South in the Miami City Cemetery most likely came Florida conditions, as at least one tree has from Plant Introduction No. 59293 of Dr. done to date, there may well be possibilities Thompson's which arrived in Washington, D. for this new tree crop in this hemisphere. C, April 19, 1924. 1. Lynch, S. J., and H. S. Wolfe. Khaya The Khaya nyasica plantings among Carib nyasica, a new mahogany for South Florida. bean pine at the Sub-Tropical Experiment Sta Proc. Florida State Hort. Soc. 55:113-116, 1942. tion (2) continue to show promise, as well as 2. Lynch, S. J., and H. S. Wolfe. Future plantings at the Dade County nursery on Red may see mahogany forests in Florida. Florida Road, Coconut Grove, Miami, Florida. More Grower, August, 1942. NEW DISEASE-RESISTANT ROOTSTOCKS URGENTLY NEEDED BY CITRUS GROWERS WALTER T. -

Root Samples Provide Early and Improved Detection of Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus in Citrus W

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Root samples provide early and improved detection of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus in Citrus W. Evan Braswell1,4, Jong‑Won Park2,4, Philip A. Stansly3,5, Barry Craig Kostyk3, Eliezer S. Louzada2, John V. da Graça2 & Madhurababu Kunta2* Huanglongbing (HLB), or Citrus Greening, is one of the most devastating diseases afecting agriculture today. Widespread throughout Citrus growing regions of the world, it has had severe economic consequences in all areas it has invaded. With no treatment available, management strategies focus on suppression and containment. Efective use of these costly control strategies relies on rapid and accurate identifcation of infected plants. Unfortunately, symptoms of the disease are slow to develop and indistinct from symptoms of other biotic/abiotic stressors. As a result, diagnosticians have focused on detecting the pathogen, Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, by DNA‑based detection strategies utilizing leaf midribs for sampling. Recent work has shown that fbrous root decline occurs in HLB‑afected trees before symptom development among leaves. Moreover, the pathogen, Ca. Liberibacter asiaticus, has been shown to be more evenly distributed within roots than within the canopy. Motivated by these observations, a longitudinal study of young asymptomatic trees was established to observe the spread of disease through time and test the relative efectiveness of leaf‑ and root‑based detection strategies. Detection of the pathogen occurred earlier, more consistently, and more often in root samples than in leaf samples. Moreover, little infuence of geography or host variety was found on the probability of detection. Huanglongbing (HLB) disease is ravaging the Citrus industry around the world. -

New Insights in Citron (Citrus Medica L.) Genomics and Fruit Development Eliezer E

HORTSCIENCE 52(6):823–826. 2017. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI11142-16 New Insights in Citron (Citrus medica L.) Genomics and Fruit Development Eliezer E. Goldschmidt1 Institute of Plant Sciences and Genetics in Agriculture, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, P.O. Box 12, Rehovot 76100, Israel Additional index words. fingered citron, genomics, persistent style Abstract. The citron (Citrus medica L.) is one of the forefathers of the citrus tribe and was the first Citrus to reach the Mediterranean, according to Theophrastus’ testimony (Tolkowsky, 1938). Citron’s biology is inseparable from its cultural and traditional legacy, from the Classic period until now. The rapidly evolving molecular tools and the increasing availability of germplasm enable reconstruction of the genomic pathway of citrus evolution and speciation. The recent progress in citron genomics is reviewed, paying special attention to the fingered citron. Among the unique biological traits of citrons, the persistent style (Pitam) played a special role. The biology of style persistence and its regulation by the synthetic auxin, Picloram, are described. Analysis of Jewish scripts and archaeological evidence regarding the requirement of style persistence for the use of citrons in the Feast of Tabernacles does not provide an unequivocal answer. However, citrons with a persistent style have been in high preference in recent centuries’ citron trade. The citron (Citrus medica L.) is believed diversity within the citron clade. Furthermore, bp that was missing in all noncitron acces- to be one of the ancestors of the citrus group whereas earlier studies examined Mediterra- sions, and a 357-bp deletion was exclu- (Barrett and Rhoads, 1976), but its study was nean citrons (Nicolosi et al., 2000b, 2005), sively detected in chloroplast genomes of somewhat neglected during the 20th century, and very few non-Mediterranean accessions citrons (Carbonell-Caballero et al., 2015).