BUGATTI TYPE 35 GRAND PRIX CAR and ITS VARIANTS Lance Cole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plateau 1 / Grid 1 Plateau 2 / Grid 2

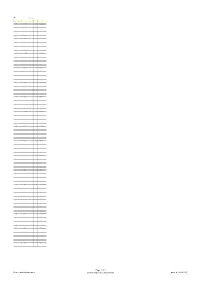

OZANNE GBR ASTON MARTIN / 2 Litres Speed / 1938 PLATEAU 1 / GRID 1 PELLETT GBR TALBOT / 105 GO54 / 1931 #❹ ALLARDET FRA CITROËN / C4 Roadster / 1932 PEROUSE / STAPTS / DAYEN FRA / FRA / FRA BUGATTI / Type 35 / 1926 ALVERGNAT / CHENUIL FRA / FRA BUGATTI / Type 35 B / 1926 PITTAWAY GBR BUGATTI / Type 35 / 1925 ALVERGNAT / CHENUIL FRA / FRA RILEY / MPH / 1933 POLSON GBR TALBOT LONDON / 90 "PL 3" / 1930 ASHWORTH GBR ASTON MARTIN / Ulster / 1935 QUIRIERE / DUPIN / DUPIN FRA / FRA / FRA BUGATTI / Type 35 B / 1926 BALLY / LESEUR / SARRAILH FRA / FRA / FRA BMW / 328 Roadster / 1938 RICCI / STOESSER FRA / FRA BMW / 328 Roadster / 1938 BATCHELOR GBR BENTLEY / 4,5l Tourer / 1928 RIVETT / MITCHELL GBR / GBR BMW / 328 Roadster / 1938 BESSADE / BESSADE FRA / FRA DELAGE / 3 litre Sport / 1936 ROLNER DNK BENTLEY / 4 1/2 Litre / 1928 BIRCH / BURNETT / BRADLEY GBR / GBR / GBR TALBOT / 105 JJ93 / 1934 ROSSETTI CHE RILEY / TT Sprite / 1936 BLAKEMORE / WOOD GBR / GBR ASTON MARTIN / Speed Model / 1936 SCHOOP DEU TALBOT LONDON / 90 "PL 4" / 1930 BRADLEY / BRADLEY GBR / GBR ASTON MARTIN / Ulster / 1936 SCHRAUWEN BEL SINGER / LM / 1936 BRANDT DEU LAGONDA / LG 45 / 1937 SCHYRR / CHANOINE FRA / FRA RILEY / Sprite / 1935 BURKARD CHE BUGATTI / Type 51 / 1932 SEBBA / COLE GBR / GBR MORGAN / 4/4 / 1937 BURNETT / BIRCH / BELL GBR / GBR / GBR ALTA / Sports / 1939 SLIJPEN NLD BUGATTI / T 43 GS / 1928 BURNETT / BIRCH / BRADLEY GBR / GBR / GBR TALBOT / 105 BGH 21 / 1934 SLIJPEN NLD TALBOT LONDON / 90 "PL 2" / 1930 BURNETT / BIRCH / BRADLEY GBR / GBR / GBR TALBOT / 105 GO52 -

NEC Classic Show

THE OFFICIAL ALFA ROMEO OWNERS CLUB EAST MIDLANDS NEWSLETTER ■ November 2018 ■ Issue 214 Coming up ... NEC Classic Show 9-11 November November Meeting The Classic Motor Show at the NEC is a hugely automotive exhibitors George & Dragon Thringstone enjoyable event for car fans. AROC has been and traders, with Weds 14 November from 7.30pm involved with it since its inception in the 1990s, and everything from books today it holds a key place in the Club’s events diary, and models to Our November meeting night will include the Our Section has been engaged in the AROC paintings and detailing gear. There’s also the infamous ‘What’s it worth’ quiz, with some nice display’s organisation there since 2001, when the Silverstone auction to see plus motoring celebrities prizes. Nothing strenuous, it’s all multiple new car on show was the 147, now often regarded including The Wheeler Dealers and many choice guesswork vaguely based around the as a Modern Classic! Generally the Club has had a more.’ Importantly, this is the biggest Classic car value of Italian Classic Cars, but other stuff gets theme each time for example; coupés, Spiders, show for car clubs now in the world, and over thrown in…. It’s a good laugh too! Quadrifoglios. Last year it was ‘Modified Alfas’ and 72,000 people are expected across the 3 days of included a lot of newer models tagged as Future or opening. Modern Classics. For 2018 we’re going back to the If you fancy going you can get a handy discount more traditional definition with, bar a couple, all on tickets for Saturday and/or Sunday using the cars being over 25 years of age, and some a lot AROC discount code which is on the members’ older than that. -

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

Bugatti Owners Club Prestcott Hillclimb 27Th /28Th June 2015

Bugatti Owners Club Prestcott Hillclimb 27th /28th June 2015 Class Q BOC 'Cheltenham Porsche Specialists' 'B' Licence Championship Target Time: 49.00 secs. Record: Mike Guest Caterham Roadsport 'K' 1800cc. 49.40 secs. (5/10/13) No. Name Car c.c. Year H'capDiff Run 1 Run 2 Award 39 Graham Holdstock Caterham Seven 1600 2003 53.30 - 0.96 52.69 52.34 1st 26 John Wells Mazda MX-5 1800 1999 56.00 - 0.77 55.23 56.40 2nd 34 Rob Meredith Ford Fiesta XR2 1617 1989 53.99 - 0.70 53.34 53.29 3rd 27 Ben Fisher Mazda MX-5 1600 1990 60.00 - 0.68 59.47 59.32 40 John Brunner Ginetta G20 - Zetec 1800 2000 57.00 - 0.62 56.96 56.38 41 Andy Mitchelmore Lotus Elise llls 1796 2005 53.46 - 0.51 53.21 52.95 33 Simon Cox Austin Mini Ritz 1380 1985 56.81 - 0.49 56.32 56.65 21 Chris Spring Toyota MR2 1998 1991 60.89 - 0.36 61.02 60.53 22 Christopher Stone Renault Clio 182 2000 2005 57.36 - 0.35 57.01 57.38 721 Ian Spring Toyota MR2 1998 1991 59.81 - 0.35 60.06 59.46 722 John Stevens Renault Clio 182 2000 2005 58.40 - 0.25 58.22 58.15 32 Ryan Eamer MG Metro - 'A' Series 1380 1980 56.68 0.03 56.71 57.60 36 Mark Newcombe MG B 1840 1978 64.00 0.15 65.89 64.15 35 Matt Langford Subaru Impreza WRX 1994t 2001 53.00 0.35 53.52 53.35 29 Shaun West Maxda MX-5 1998 2009 55.00 0.45 55.45 55.59 31 Dominic Moorland Mini Cooper 1275 1993 64.00 0.56 64.78 64.56 42 Alistair Clark Lotus Elise S1 - 'K' Series 1796 1998 53.13 1.12 55.05 54.25 28 Michael Gale Mazda MX-5 1800 1996 58.00 1.46 59.49 59.46 24 Peter Warren Mazda MX-5 1600 1991 60.10 1.79 61.89 62.69 23 Rob Gutteridge Mazda MX-5 1840 1998 63.00 1.79 67.22 64.79 38 Phil Saddington Westfield Sei - X Flow 1700 2001 57.00 1.85 59.65 58.85 25 Gail Meloy Mazda MX-5 1840 1999 64.16 2.24 66.40 66.96 37 Peter Neale Austin Healey Sprite Mk1 1275 1961 64.00 14.73 78.73 20 Nic Houslip MGB Roadster 1800 1972 66.80 30 Chris Webb Mazda MX-5 1840 2000 55.62 720 Debbie Woods MG B V8 3528 1965 65.00 Class R1 Midland Championship 'B' licence Road Car class Record: Michael Andrews Westfield SE-VX 1998cc 56.92 secs No. -

100 Years of Bugatti at Concorso D'eleganza

100 years of Bugatti at Concorso d’Eleganza Villa d’Este CERNOBBIO 26 04 2009 IN A FURTHER HIGHLIGHT ON THIS YEAR’S AGENDA OF CENTENNIAL CELEBRATIONS, BUGATTI AUTOMOBILES S.A.S. PRESENTED FOUR BUGATTI VEYRON SPECIALS AT VILLA D’ESTE CONCORSO D’ELEGANZA. In a further highlight on this year’s agenda of centennial celebrations, Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. presented four Bugatti Veyron specials at Villa d’Este Concorso d’Eleganza. These one off models are reminders of Bugatti’s glorious motor-racing history which played a central role in popularising and ultimately establishing the myth which the brand continues to enjoy to this day. The Bugatti brand is almost inextricably linked to the Type 35. The Type 35 Grand Prix was by far the most successful racing model. The unmistakable radiator grille and eight-spoke aluminium wheels of the Type 35 have become defining features of the Bugatti automobile. In its day, the Grand Prix was also well ahead of its time in terms of engineering ingenuity. The front axle design of this vehicle, which, for reasons of weight minimisation, is hollow, is a true masterpiece of workmanship and was deemed nothing less than revolutionary. Its springs were passed through the axle to produce a high level of stability. The Grand Prix’s brake drums were integrally fitted into its lightweight aluminium wheels. Unfastening the central wheel nut allowed the wheel to be easily removed within a matter of seconds and the brake to be exposed. This was a crucial advantage at the pit stop. 2000 wins in ten years The blue racers made their first appearance on the race track at the Grand Prix held by Automobil Club de France in Lyon in 1924. -

Aerospecials L’Eredità Dei Cieli Della Grande Guerra Automobili Italiane Con Motori Aeronautici

Aerospecials L’eredità dei cieli della Grande Guerra Automobili italiane con motori aeronautici AISA - Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile MONOGRAFIA AISA 106 I Aerospecials L’eredità dei cieli della Grande Guerra Automobili italiane con motori aeronautici AISA - Associazione Italiana per la Storia dell’Automobile in collaborazione con Biblioteca Comunale, Pro Loco di San Piero a Sieve (FI) e “Il Paese delle corse” Auditorium di San Piero a Sieve, 28 marzo 2014 2 Prefazione Lorenzo Boscarelli 3 Emilio Materassi e la sua Itala con motore Hispano-Suiza Cesare Sordi 8 Auto italiane con motore aeronautico negli anni Venti Alessandro Silva 21 Alfieri Maserati e le etturev da corsa con motore derivato dagli Hispano-Suiza V8 Alfieri Maserati 23 Auto a turbina degli anni Sessanta: le pronipoti delle AeroSpecials Francesco Parigi MONOGRAFIA AISA 106 1 Prefazione Lorenzo Boscarelli l fascino della velocità fu uno degli stimoli che in- I motori aeronautici divennero sempre più potenti Idussero molti pionieri dell’automobile ad appas- e di conseguenza di grande cilindrata, tanto che il sionarsi al nuovo mezzo, tanto che fin dai primordi loro impiego dalla seconda metà degli anni Venti in furono organizzate competizioni e le potenze delle poi fu quasi esclusivamente limitato alle vetture per vetture crebbero in pochi anni da pochissimi cavalli i record di velocità terrestre. a diverse decine e ben presto superarono i cento. La disponibilità di motori a turbina, di ingombro Questi progressi imposero una rapida evoluzione ridotto e con rapporto potenza/peso molto eleva- delle tecnologie utilizzate dall’automobile, che per to, negli anni Sessanta indusse alcuni costruttori ad alcuni anni fu il settore di avanguardia per lo svilup- adottarli su vetture per gare di durata, da Gran Pre- po dei materiali, delle soluzioni costruttive e di tec- mio e per la Formula USAC (“Indianapolis”). -

The Lost Bugatti

BUGATTI DIATTO AVIO 8C WORDS CLAUDE TEISEN-SIMONY & DAVID LILLYWHITE ARCHIVE PICTURES BUGATTI TRUST A mysterious chassis fitted with a one-off Bugatti aero engine, discovered in a Turin museum, turns out to have links to a famous pilot and to Maserati’s first car. But could it also have been the first step towards the super-luxury Bugatti Royale saloon? The lost Bugatti 90 / MAGNETO MAGNETO / 91 BUGATTI DIATTO AVIO 8C T This is one hell of a tale. It’s controversial at times, it brings in threads involving World War One fighter pilot Roland Garros, surprising links to Maserati, and the likely origins of not just Bugatti’s Grand Prix engines, but also the legendary Bugatti Royale. Most exciting of all, it introduces a remarkable aero-engined Bugatti that’s never been seen before. To whet your appetite, it’s a 14.5-litre and develops 250bhp at 2160rpm – Bugatti’s equivalent of the ‘Beast of Turin’ Fiat or the Benz-engined Scariscrow. Crucially, a large proportion of it is original, rescued from decades in hiding by a legendary Bugatti expert before moving on to its current owner. It’s been painstakingly researched, restored and part-recreated in secret by craftsmen in Denmark and the Czech Republic. To all but a select few, its existence remained unknown until its big reveal at the Rétromobile show in Paris on February 6. So, how did we get to this point? Let’s start with the engine, because actually it’s more important than the car itself in many ways. The story begins with French pilot Roland Garros, who in 1913 made the first-ever non-stop flight across the Mediterranean, flying a fast Morane-Saulnier monoplane. -

Michael Banfield Collection

The Michael Banfield Collection Friday 13 and Saturday 14 June 2014 Iden Grange, Staplehurst, Kent THE MICHAEL BANFIELD COLLECTION Friday 13 and Saturday 14 June 2014 Iden Grange, Staplehurst, Kent, TN12 0ET Viewing Please note that bids should be ENquIries Customer SErvices submitted no later than 16:00 on Monday to Saturday 08:00 - 18:00 Thursday 12 June 09:00 - 17:30 Motor Cars Thursday 12 June. Thereafter bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Friday 13 June from 09:00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 should be sent directly to the Saturday 14 June from 09:00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax Please call the Enquiries line Bonhams office at the sale venue. [email protected] when out of hours. +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax Sale times Automobilia Please see page 2 for bidder We regret that we are unable to Friday 13 June +44 (0) 8700 273 619 information including after-sale Automobilia Part 1 - 12 midday accept telephone bids for lots with collection and shipment a low estimate below £500. [email protected] Saturday 14 June Absentee bids will be accepted. Automobilia Part 2 - 10:30 Please see back of catalogue New bidders must also provide Motor Cars 15:00 (approx) for important notice to bidders proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do so may result Sale Number Illustrations in your bids not being processed. 22201 Front cover: Lot 1242 Back cover: Lot 1248 Live online bidding is CataloguE available for this sale £25.00 + p&p Please email [email protected] Entry by catalogue only admits with “Live bidding” in the subject two persons to the sale and view line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service Bids +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax To bid via the internet please visit www.bonhams.com Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. -

In Safe Hands How the Fia Is Enlisting Support for Road Safety at the Highest Levels

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF THE FIA: Q1 2016 ISSUE #14 HEAD FIRST RACING TO EXTREMES How racing driver head From icy wastes to baking protection could be deserts, AUTO examines how revolutionised thanks to motor sport conquers all pioneering FIA research P22 climates and conditions P54 THE HARD WAY WINNING WAYS Double FIA World Touring Car Formula One legend Sir Jackie champion José Maria Lopez on Stewart reveals his secrets for his long road to glory and the continued success on and off challenges ahead P36 the race track P66 P32 IN SAFE HANDS HOW THE FIA IS ENLISTING SUPPORT FOR ROAD SAFETY AT THE HIGHEST LEVELS ISSUE #14 THE FIA The Fédération Internationale ALLIED FOR SAFETY de l’Automobile is the governing body of world motor sport and the federation of the world’s One of the keys to bringing the fight leading motoring organisations. Founded in 1904, it brings for road safety to global attention is INTERNATIONAL together 236 national motoring JOURNAL OF THE FIA and sporting organisations from enlisting support at the highest levels. over 135 countries, representing Editorial Board: millions of motorists worldwide. In this regard, I recently had the opportunity In motor sport, it administers JEAN TODT, OLIVIER FISCH the rules and regulations for all to engage with some of the world’s most GERARD SAILLANT, international four-wheel sport, influential decision-makers, making them SAUL BILLINGSLEY including the FIA Formula One Editor-in-chief: LUCA COLAJANNI World Championship and FIA aware of the pressing need to tackle the World Rally Championship. Executive Editor: MARC CUTLER global road safety pandemic. -

Dealer Distribution Codes Page 1 of 1

Dealer Distribution Overview Dealer Names and Addresses FORD Short Postal Delivery Location Dealer Destination Name Postalcode City Street Code Code Shiremoor 278 GA Arnold Clark NE27 0NB NE Shiremoor New York Road, Algernon Industrial Estate South Shields 334 GA Jennings Ford NE34 9PQ NE South Shields Newcastle Road Shiremoor 460 GA Arnold Clark NE27 0NB NE Shiremoor New York Road, Algernon Industrial Estate Dunston 553 GA Jennings Ford NE8 2TZ NE Dunston Eslington Park Birtley 732 GA Arnold Clark DU3 2SN DU Birtley Portobello Road South Shields D06 GA Dagenham Motors Plaistow NE34 9NP NE South Shields C/O Jarrow Slake South Shields PB6 GA Paragon Vehicle Services NE34 9PN NE South Shields Port Of Tyne Sunderland SR5 GA Addison Motors Ltd SR5 1JE SR Sunderland T/A Benfield Ford, Newcastle Road South Shields W18 GA Brunel Ford NE34 9PN NE South Shields C/O Walon Limited, Jarrow Slake Birtley SM7 GA Sma Newcastle DH3 2SA DH Birtley Portobello Ind Estate, Shadon Way Bridgend 006 GB Bridgend Ford CF31 3BF CF Bridgend Cowbridge Rd, Waterton Ind Estate Blackpole 031 GB Bristol Street Motors WR3 8UA WR Blackpole Cosgrove Close Tewkesbury 034 GB Bristol Street Motors GL20 8HG GL Tewkesbury Cowfield Mill, Off Northway Lane Brecon 117 GB Brecon Ford LD3 8BT LD Brecon Brecon Enterprise Park, Warren Road Oswestry 135 GX Furrows Ltd SY11 1JE SY Oswestry Whittington Road Telford 137 GB Furrows Of Telford TF1 4JF TF Telford Haybridge Road, Wellington Blackwood 145 GB Arrow Ford NP12 2JG NP Blackwood Commercial Street, Pontllanfraith Cardiff 149 GB Evans Halshaw Cardiff CF3 2ER CF Cardiff Wentloog Coroprate Park, Wentloog Wentloog 171 GB Fordthorne CF3 2ER CF Wentloog Wentloog Corporate Park, Wentloog Road Cardigan 204 GB Davies Motors SA43 1LZ SA Cardigan Rhos Garage, Aberystwyth Road Kidderminster 216 GB Bristol Street Motors DY10 1JB DY Kidderminster C/O Hills Ford, Worcester Road Cwmbran 257 GB Cwmbran Ford NP44 1TT NP Cwmbran Avondale Road Newport 264 GB Newport Ford NP19 4QU NP Newport Leeway Ind. -

A Catalogue of Motoring & Motor Racing Books April 2021

A catalogue of Motoring & Motor Racing Books April 2021 Picture This International Limited Spey House, Lady Margaret Road, Sunningdale, UK Tel: (+44) 7925 178151 [email protected] All items are offered subject to prior sale. Terms and Conditions: Condition of all items as described. Title remains with Picture This until payment has been paid and received in full. Orders will be taken in strict order of receipt. Motoring & Motor Racing Books Illustrations of all the books in this catalogue can be found online at: picturethiscollection.com/products/books/books-i/motoringmotorracing/en/ SECTION CONTENTS: 01-44 AUTO-BIOGRAPHIES & BIOGRAPHIES 45-67 ROAD AND RACING CARS 68-85 RACES, CIRCUITS, TEAMS AND MOTOR RACING HISTORY 86-96 MOTOR RACING YEARBOOKS 97-100 LONDON-SYDNEY MARATHON, 1968 101-111 PRINCES BIRA & CHULA 112-119 SPEED AND RECORDS 120-130 BOOKS by and about MALCOLM CAMPBELL 131-142 TOURING AND TRAVELS AUTO-BIOGRAPHIES & BIOGRAPHIES [in alphabetical order by subject] 1. [SIGNED] BELL, Derek - My Racing Life Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens, 1988 First edition. Autobiography written by Derek Bell with Alan Henry. Quarto, pp 208. Illustrated throughout with photographs. Blue cloth covered hard boards with silver lettering to the spine; in the original dust jacket which has been price clipped. SIGNED and inscribed “ _________ my best wishes | Derek Bell | 15.7.03”. Bell won at Le Mans five times with Porsche as well as the Daytona 24 three times and was World Sports Car Champion twice in the mid 1980’s. Fine condition book in a price clipped but otherwise Fine jacket. [B5079] £85 2. -

High River 1997 Oct High River

10 GLEICHEN—GLEICHEN ^^^^^^__000120^_TELUSAdyerUangSavicesI^ Siksika Nation Tribal (Contd) Storm Adeline 734-2861 TRANSALTA UTIUTIES CORPORATION' ROYAL CANADIAN Or (Contd)' Stott Leonard Boxl28 734-2546 Strathmore Office Communications 734-5247 Stott Leonard Bronk Box128 734-2500 11 Bayside Place Strattimore 934-3144 MOUNTED POUCE Communications CorpFax line..... 734-2355 STRATHMORE VALUE DRUG MART Bassano Office (No Ctiarge Agrtailtiire Dial) 1-800-364-4928 Complaints 24Iks 734-3923 CalgaryCustomersOirectLine(NoCharge) ....265-1275 132 2Av Strathmore 934-3122 Administration-Info 734-3056 Emergency Calls Only 24 Mrs ENA .....734-5240 After Hours Call Res 934-5574 Strathmore Office 934-4248 RoyalClive 734-3603 Education 734-5220 Sun WalkR 734-3370 Bassano Office (No Charge RoyalD 734-2748 Fax Line 734-2505 Talbott Percy Boxl94 734-3944 Dial) 1-800-364-4928 RunningRabbit AmoW 734-21W Calgary CustomersDirect Line (No Turbo 734-3464 RunningRabbit C Box33l .734-3340 Charge) 265-1128 TARGET AIRSPRAY LTD Turko Kevin KddenValleyResort 734-2980 Running Rabbit Joanne 734-3067 Family Services 734-5140 TurningRobe Clinton Boxl303 734-2694 Running Rabbit K 734-3085 Finance & Administration 734-5170 RRl Strathmore 934-4353 Tumingrobe Frank Sr Box335 734-2512 Calgary Customers Direct Line (No Running Rabbit M 734-3111 Teiford R Boxlld 734-3945 Turning Robe Marceila 734-3372 Running Rabbit M 734-3924 aarge) 265-1371 Tumingrope G 734-3565 Running Rabbit Mavis 734-3166 Fire Dept CeMar 934-8207 Twohorns Lionel i..734-3330 Runimg Rabbit Mavis 734-3665 Housing