Outline of Daniel 11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Egypt Under the Ptolemies

UC-NRLF $C lb EbE THE HISTORY OF EGYPT THE PTOLEMIES. BY SAMUEL SHARPE. LONDON: EDWARD MOXON, DOVER STREET. 1838. 65 Printed by Arthur Taylor, Coleman Street. TO THE READER. The Author has given neither the arguments nor the whole of the authorities on which the sketch of the earlier history in the Introduction rests, as it would have had too much of the dryness of an antiquarian enquiry, and as he has already published them in his Early History of Egypt. In the rest of the book he has in every case pointed out in the margin the sources from which he has drawn his information. » Canonbury, 12th November, 1838. Works published by the same Author. The EARLY HISTORY of EGYPT, from the Old Testament, Herodotus, Manetho, and the Hieroglyphieal Inscriptions. EGYPTIAN INSCRIPTIONS, from the British Museum and other sources. Sixty Plates in folio. Rudiments of a VOCABULARY of EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS. M451 42 ERRATA. Page 103, line 23, for Syria read Macedonia. Page 104, line 4, for Syrians read Macedonians. CONTENTS. Introduction. Abraham : shepherd kings : Joseph : kings of Thebes : era ofMenophres, exodus of the Jews, Rameses the Great, buildings, conquests, popu- lation, mines: Shishank, B.C. 970: Solomon: kings of Tanis : Bocchoris of Sais : kings of Ethiopia, B. c. 730 .- kings ofSais : Africa is sailed round, Greek mercenaries and settlers, Solon and Pythagoras : Persian conquest, B.C. 525 .- Inarus rebels : Herodotus and Hellanicus : Amyrtaus, Nectanebo : Eudoxus, Chrysippus, and Plato : Alexander the Great : oasis of Ammon, native judges, -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

Περίληψη : Seleucus I Nicator Was One of the Most Important Kings That Succeeded Alexander the Great

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Σκουνάκη Ιουλία Μετάφραση : Κόρκα Αρχοντή Για παραπομπή : Σκουνάκη Ιουλία , "Seleucus I Nicator", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=9750> Περίληψη : Seleucus I Nicator was one of the most important kings that succeeded Alexander the Great. Originally a mere member of the corps of the hetaeroi, he became an officer of the Macedonian army and, after taking advantage of the conflict among Alexanderʹs successors, he was proclaimed satrap of Babylonia. After a series of successful diplomatic movements and military victories in the long‑lasting wars against the other Successors, he founded the kingdom and the dynasty of the Seleucids, while he practically revived the empire of Alexander the Great. Άλλα Ονόματα Nicator Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης Europos, 358/354 BC Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου Lysimacheia, 280 BC Κύρια Ιδιότητα Officer of the Macedonian army, satrap of Babylonia (321-316 BC), founder of the kingdom (312 BC) and the dynasty of the Seleucids. 1. Biography Seleucus was born in Macedonia circa 355 BC, possibly in the city of Europos. Pella is also reported to have been his birth city, but that is most likely within the framework of the later propaganda aiming to present Seleucus as the new Alexander the Great.1He was son of Antiochus, a general of Philip II, and Laodice.2 He was about the same age as Alexander the Great and followed him in his campaign in Asia. He was not an important soldier at first, but on 326 BC he led the shieldbearers (hypaspistai)in the battle of the Hydaspes River against the king of India, Porus (also Raja Puru). -

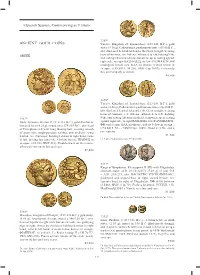

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30Am ANCIENT GOLD COINS

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30am 3389* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Thrace, Kingdom of, Lysimachos, (323-281 B.C.), gold stater, (8.36 g), Callatis mint, posthumous issue c.88-86 B.C., obv. diademed head of Alexander the Great to right, wearing GREEK horn of Ammon, rev. Athena enthroned to left, holding Nike and resting left arm on shield, transverse spear resting against right side, to right ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩ[Σ], to left ΛΥΣΙΜΑΧΟΥ, HP monogram below arm, ΚΑΛ on throne, trident below in exergue, (cf.S.6813, M.266, SNG Cop.1089). Extremely fi ne and virtually as struck. $4,500 3390* Thrace, Kingdom of, Lysimachos, (323-281 B.C.), gold stater, (8.26 g), Callatis mint, posthumous issue c.88-86 B.C., obv. diademed head of Alexander the Great to right, wearing horn of Ammon, rev. Athena enthroned to left, holding 3387* Nike and resting left arm on shield, transverse spear resting Sicily, Syracuse, Hieron II, (275-215 B.C.), gold drachm or against right side, to right ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ, to left ΛΥΣΙΜΑΧΟΥ, hundred litrai (4.25 g), struck circa 275-263 B.C., obv. head ΦΜ under arm, ΚΑΛ on throne, trident below in exergue, of Persephone left with long fl owing hair, wearing wreath (cf.S.6813, M.-, cf.SNG Cop. 1089). Good very fi ne and a of grain ears, single-pendant earring, and necklace, wing rare variety. behind, rev. charioteer, holding kentron in right hand, reins $1,300 in left, driving fast biga left, A below horses, ΙΕΡΩΝΟΣ in Ex Noble Numismatics Sale 79 (lot 3208). -

The Contest for Macedon

The Contest for Macedon: A Study on the Conflict Between Cassander and Polyperchon (319 – 308 B.C.). Evan Pitt B.A. (Hons. I). Grad. Dip. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Tasmania October 2016 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does this thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 ii Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed alone, and I am forever grateful to my supervisor, mentor and friend, Dr Graeme Miles, who has unfailingly encouraged and supported me over the many years. I am also thankful to all members of staff at the University of Tasmania; especially to the members of the Classics Department, Dr Jonathan Wallis for putting up with my constant stream of questions with kindness and good grace and Dr Jayne Knight for her encouragement and support during the final stages of my candidature. The concept of this thesis was from my honours project in 2011. Dr Lara O’Sullivan from the University of Western Australia identified the potential for further academic investigation in this area; I sincerely thank her for the helpful comments and hope this work goes some way to fulfil the potential she saw. -

The Princess of Egypt Must Die Stephanie Dray

The Princess of Egypt Must Die Stephanie Dray Copyright © 2012 Stephanie Dray All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in whole or in part in any form by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, is forbidden without written permission. This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental. Discover other titles by Stephanie Dray at http://www.stephaniedray.com THE PRINCESS OF EGYPT MUST DIE by Stephanie Dray "Remember always that you’re a royal princess of Egypt," my mother says, wiping tears from my cheeks. "But I'm not the only one.” There is also Lysandra, my half-sister. The source of my tears. My mother uses clean linen strips to bandage my bleeding knees, both of which were scraped raw when Lysandra nearly trampled me beneath the hooves of her horse. "You mustn't let Lysandra bully you." "She's never punished for it," I complain. "She knows she can do as she pleases just because she is the daughter of the king's chief wife." "Not for long," my mother vows. "Soon, I will be first wife here." My father's harem is filled with women who wait upon his every whim. He has wives and concubines and even hetaeras like Thais, who sells her favor to the king. -

An Ill-Defined Rule: Cassander’S Consolidation of Power

Karanos 2, 2019 33-42 An Ill-defined Rule: Cassander’s Consolidation of Power by Evan Pitt University of Tasmania [email protected] ABSTRACT Cassander’s implementation of power during the early stages of his rule of Macedonia was wide ranging and multifaceted. He employed numerous different strategies to gain support from a variety of influential groups within the Macedonian homeland and adjacent areas to secure his position. Much of the discussion surrounding Cassander’s actions to accomplish control over Macedonia has focussed on his desire to become the next king in Macedonia as demonstrated by overt public actions, a feat he achieved after the Peace of 311. However, when one considers the coinage issued by Cassander prior to 311, this single-minded monarchic aim appears less evident, calling into question the strength of this understanding of his actions. KEYWORDS Cassander, Antipatrid, Hellenistic monarchy, coins, Diadochi, governor. The winter of 317/316 BCE was a watershed moment for the Macedonian Empire and for the political landscape of the Macedonian homeland. Cassander, son of the former regent Antipater, had launched a successful invasion of Macedonia, ousting the incumbent regent, Polyperchon from power. From this point Cassander would embark on an ambitious plan to control the region. Over the following years he put in place a wide ranging and multifaceted strategy that drew upon many and varied avenues of support to cement his position. This period of time would see Cassander marry into the Argead family, initiate a significant building program in northern and southern Greece, remove the young Alexander IV from court, and bury the royal couple, Philip III Arrhidaeus and Adea-Eurydice at the traditional Argead burial ground at Aegae. -

Ptolemy I Soter, the First King of Ancient Egypt's Ptolemaic Dynasty

Ptolemy I Soter, The First King of Ancient Egypt’s Ptolemaic Dynasty Article by Jimmy Dunn In the ancient world, there is no surprise that military men often became rulers. These men, most of whom rose through the military ranks, usually had considerable administrative skills and had proved themselves to be leaders. Almost certainly the first man to unite Egypt at the dawn of civilization was a military man who became king, and this tradition has been followed throughout the history of the world, up unto our present times. Alexander the Great built an empire during the latter part of the first millennium BC, including Egypt which he captured in about 332 BC. Though he ordered the building of a great city in his name on the Egyptian Mediterranean coast, he was not finished with his conquests and would soon depart the country, leaving behind a banker of Naucratis named Cleomenes as Egypt's satrap, or governor. He was greatly despised. Demosthenes called him "Ruler of Egypt and dishonest manipulator of the country's lucrative grain trade". Aristotle even spoke up, concurring and citing Cleomenes' numerous incidents of fraudulent conduct with merchants, priests of the temple and government officials. The Roman historian Arrian added his own assessment, telling us that "he was an evil man who committed many grievous wrongs in Egypt" When Ptolemy I took over the post from Clemones in Egypt, he had little option but to try, sentence and execute Cleomenes. Ptolemy I is thought to have been the son of Lagus, a Macedonian nobleman of Eordaea. -

Royal Macedonian Widows: Merry and Not Elizabeth D

Royal Macedonian Widows: Merry and Not Elizabeth D. Carney RANZ LEHÁR’S OPERETTA Die lustig Witwe debuted in Vienna in December of 1905 and, as The Merry Widow, F from 1907 on, attracted large audiences in the English- speaking world. It proved an enduring international success, spawning generations of revivals as well as a spin-off ballet, a succession of films, and even a French television series. Lehár’s plot was set at a minor European court. It revolved around in- trigues aimed at preventing a widow, who had inherited her husband’s fortune, from remarrying someone from outside the principality, an eventuality that could somehow lead to financial disaster for the state. After some singing and dancing and a sub- plot involving more overt (and extra-marital) hanky-panky, love triumphs when the widow reveals that she will lose her fortune if she marries again, thus enabling the lover of her “youth” to marry her without looking like or actually being a fortune hunter.1 The operetta and especially its film variants depend on the intersection, however coyly displayed, of sex, wealth, and power, and, more specifically, on an understanding of widows, at least young ones, as particularly sexy.2 This aspect of the plot was especially apparent in the 1952 Technicolor Merry Widow in which Lana Turner, the eponymous widow, wore an equally 1 On Lehár and the operetta see B. Grun, Gold and Silver: The Life and Times of Franz Lehár (New York 1970). The1861 French play that helped to shape the plot of the operetta was Henri Meilhac’s L’Attaché d’ambassade (Grun 111– 112). -

The Families of Ptolemy I Soter Sheila Ager University of Waterloo

Building a Dynasty: the Families of Ptolemy I Soter Sheila Ager University of Waterloo Lagos Arsinoë Antipater Artakama Thaïs Ptolemy I Soter Eurydike Ptolemy Lysandra Meleager? Keraunos Lagos Argaios? Leontiskos Unnamed son Ptolemaïs (“Rebel in Cyprus”) Eirene Ptolemy I Soter Berenike I Philip Ptolemy II Arsinoë II Philotera Magas Theoxena? Antigone Philadelphos Philadelphos Selection of Ancient Sources: Athenaios 13.576e: This Thais, after Alexander’s death, was married to Ptolemy, the first king of Egypt, and bore to him Leontiskos and Lagos, also a daughter, Eirene. Pausanias 1.6.8: If this Ptolemy really was the son of Philip, son of Amyntas, he must have inherited from his father his passion for women, for, while wedded to Eurydike, the daughter of Antipater, although he had children he took a fancy to Berenike, whom Antipater had sent to Egypt with Eurydike. He fell in love with this woman and had children by her, and when his end drew near he left the kingdom of Egypt to Ptolemy (from whom the Athenians name their tribe) being the son of Berenike and not of the daughter of Antipater. Appian Syr. 62: This Keraunos was the son of Ptolemy Soter and Eurydike, the daughter of Antipater. He had left Egypt from fear, because his father had decided to leave the kingdom to his youngest son. Pausanias 1.7.1: This Ptolemy [II] fell in love with Arsinoë [II], his full sister, and married her, violating herein Macedonian custom, but following that of his Egyptian subjects. Secondly he put to death his brother Argaios, who was, it is said, plotting against him… He put to death another brother also, son of Eurydike, on discovering that he was creating disaffection among the Cyprians. -

Ptolemaic Dynasty

Macquarie University Museum of Ancient Cultures Ptolemaic Dynasty The Ptolemaic dynasty flourished in Egypt from 323 until 31 BC. Ptolemy I Sōtēr began with the satrapy of Egypt, but at times the kingdom also included Kyrene, Koile-Syria, Cyprus, various islands in the Aegean Sea, Crete, and parts of Syria and Asia Minor. The Ptolemaic kingdom survived until Ptolemy’s great-great-great-great- great-great-great-great grandson Ptolemaios XV Caesar was executed by Octavian in 31 BC. Macquarie University Museum of Ancient Cultures Ptolemy I Soter “the Saviour” (ca.360-282 BC). Ptolemy I Soter (Ptolemaios in Greek), was one of the most successful of the diadochoi. An astute and capable strategist, Ptolemy exploited his position as satrap of Egypt (a secure, stable and virtually impregnable satrapy) to establish a dynasty that lasted until the death of Cleopatra VII in 31 BC. Ptolemy was perhaps the only one of the first generation of diadochoi to die peacefully. Ptolemy was probably the son of Macedonian noble named Lagos,1 and a Macedonian woman named Arsinoë, although it was rumoured that he was a bastard son of Philip II.2 Ptolemy was brought up at Philip’s court in Pella, and was one of the boyhood companions (syntrophoi) of Alexander the Great. Like Alexander the Great, Hephaistion and Kassandros he was educated by the famous philosopher Aristotle. In 336 Ptolemy was banished from Macedon along with Harpalos, Nearchos and Erygios for their part in the so-called “Pixodaros affair”.3 He was recalled shortly afterwards when Alexander succeeded to the throne after the assassination of Philip II. -

Alexander the Great, the Royal Throne and the Funerary Thrones of Macedonia*

Karanos 1, 2018 23-34 Alexander the Great, the royal throne and the funerary thrones of Macedonia* by Olga Palagia National & Kapodistrian University of Athens [email protected] ABSTRACT There is no evidence in either Greece or Macedon in the archaic and classical periods that the throne functioned as a symbol of royalty. Thrones were for the gods and their priests. Only the king of Persia used a royal throne and even had portable thrones for his campaigns. This paper argues that after his conquest of the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great adopted the throne as a royal symbol; after his death, his throne became a token of his invisible presence. Philip III Arrhidaeus is known to have used a royal throne after his return to Macedonia. By implication, the marble thrones found in three tombs at Vergina–Aegae are here understood as symbols of royalty and the tombs are interpreted as royal. KEYWORDS Throne; priest; Persian king; tomb; marble; gold and ivory. Among the symbols of royalty in the kingdom of Macedon, the throne requires special investigation. We will try to show that its introduction as the seat of power may be traced to the new world order created by Alexander the Great’s conquest of Asia; we will subsequently investigate the impact of the royal throne on the funerary furniture of Macedonia. In archaic and classical Greece thrones were reserved for the gods and by extension, their priests and priestesses. Zeus, father of the gods, was often depicted enthroned. There are two obvious sculptural examples from the fifth century, the east frieze of the Parthenon1 and the cult statue created by Phidias for the temple of Zeus at Olympia.