Brainy Quote ~ Alexander the Great 002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

Il?~ ~ Editorial Offices

~ ~ ENCYCLOP.JEDIA BRITANNICA ,y 425 NORTH MICHIGAN AVENUE • CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60611 ~ ,Il?~ ~ Editorial Offices Dear Britannica Contributor: Some time ago you contributed the enclosed copy to Ency- clopaedia Britannica. We have been proud to be able to continue to publish it in the set. Because the material is no longer brand new, however, we have thought it only fair to ask you as the author whether or not its condition is still satisfactory. Are you still content to be identified as the contributor? If not, would you be willing to indicate to us changes you consider necessary? Please note that we are not asking you to undertake any major rewriting or revision at this time. If you believe that drastic changes are required, we would be glad to know that. If, on the other hand, only minor change or updating is necessary, you may if you wish make corrections on one of the two copies enclosed with this letter. (The second copy is for your own use.) We also enclose a copy of your description as it now appears in Britannica. We find that it is no longer safe to assume that a contributor's description will remain accurate for more than a brief time. If yours is out of date, or if the address to which this letter was mailed is no longer current, would you please indicate changes on the enclosed sheet? Britannica values highly the contributions of the thousands of writers represented in its volumes. We hope that you will welcome, as many of our authors have already said that they would welcome, this opportunity to review the condition of what is still being published as your statement. -

Alexander and the 'Defeat' of the Sogdianian Revolt

Alexander the Great and the “Defeat” of the Sogdianian Revolt* Salvatore Vacante “A victory is twice itself when the achiever brings home full numbers” (W. Shakespeare, Much Ado About Nothing, Act I, Scene I) (i) At the beginning of 329,1 the flight of the satrap Bessus towards the northeastern borders of the former Persian Empire gave Alexander the Great the timely opportunity for the invasion of Sogdiana.2 This ancient region was located between the Oxus (present Amu-Darya) and Iaxartes (Syr-Darya) Rivers, where we now find the modern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, bordering on the South with ancient Bactria (present Afghanistan). According to literary sources, the Macedonians rapidly occupied this large area with its “capital” Maracanda3 and also built, along the Iaxartes, the famous Alexandria Eschate, “the Farthermost.”4 However, during the same year, the Sogdianian nobles Spitamenes and Catanes5 were able to create a coalition of Sogdianians, Bactrians and Scythians, who created serious problems for Macedonian power in the region, forcing Alexander to return for the winter of 329/8 to the largest city of Bactria, Zariaspa-Bactra.6 The chiefs of the revolt were those who had *An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Conflict Archaeology Postgraduate Conference organized by the Centre for Battlefield Archaeology of the University of Glasgow on October 7th – 9th 2011. 1 Except where differently indicated, all the dates are BCE. 2 Arr. 3.28.10-29.6. 3 Arr. 3.30.6; Curt. 7.6.10: modern Samarkand. According to Curtius, the city was surrounded by long walls (70 stades, i.e. -

Central Asia Under and After Alexander

10:00—10:30 Razieh Taasob The Attribution and ORGANIZED BY Chronology of the Heraios Coinage: A Reassessment Institute of Classical Archaeology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University 10:30—11:00 Coffee break Ladislav Stančo, Anna Augustinová, Petra Cejnarová, International Jakub Havlík, Helena Tůmová conference SESSION VI: SOCIETY AND CULTURE Chairman: Gunvor Lindström Eurasia Department, German Archaeological Institute Gunvor Lindström 11:00—11:30 Guendalina Daniela Maria Taietti Alexander III’s Empire: University of Reading / Hellenistic Central Asia SEEN FROM Macedonian, Achaemenid or Oecumenic Research Network (HCARN) Greek? Rachel Mairs OXYARTES´ ROCK: 11:30—12:00 Marco Ferrario Memory and Communities in 329 B.C. Bactria: CENTRAL ASIA Beyond HDT 4. 204 12:00—12:30 Michail Iliakis Flipping the Coin: Alexander the Great’s Bactrian-Sogdian UNDER AND AFTER Expedition from a Local Perspective ALEXANDER 12:30—13:30 Lunch break 13:30—14:00 Olga Kubica Meetings with the “Naked Philosophers” as a case study for the Greco-Indian relations in the time of Alexander 14:00—14:30 Rachel Mairs The Hellenistic Far East in Historical Fiction: Ancient History, Modern Ideologies 14:30—15:00 Closing remarks and discussion Third Meeting of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network 14—16 November 2018 SESSION II: GEOGRAPHY 12:30—13:00 Viktor Mokroborodov Gishttepa Program Chairman: Laurianne Martinez-Sève and others: Recent Russian-Uzbek archaeological works in the Pashkhurd 15:00—15:30 Dmitry A. Shcheglov Alexander’s area WEDNESDAY 14 NOVEMBER 2018 Central -

The Second After the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources

The Second after the King and Achaemenid Bactria on Classical Sources MANEL GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ Universidad de Barcelona–CEIPAC* ABSTRACT The government of the Achaemenid Satrapy of Bactria is frequently associated in Classical sources with the Second after the King. Although this relationship did not happen in all the cases of succession to the Achaemenid throne, there is no doubt that the Bactrian government considered it valuable and important both for the stability of the Empire and as a reward for the loser in the succession struggle to the Achaemenid throne. KEYWORDS Achaemenid succession – Achaemenid Bactria – Achaemenid Kingship Crown Princes – porphyrogenesis Beyond the tradition that made of Zoroaster the and harem royal intrigues among the successors King of the Bactrians, Rege Bactrianorum, qui to the throne in the Achaemenid Empire primus dicitur artes magicas invenisse (Justinus (Shahbazi 1993; García Sánchez 2005; 2009, 1.1.9), Classical sources sometimes relate the 155–175). It is in this context where we might Satrapy of Bactria –the Persian Satrapy included find some explicit references to the reward for Sogdiana as well (Briant 1984, 71; Briant 1996, the prince who lost the succession dispute: the 403 s.)– along with the princes of the offer of the government of Bactria as a Achaemenid royal family and especially with compensation for the damage done after not the ruled out prince in the succession, the having been chosen as a successor of the Great second in line to the throne, sometimes King (Sancisi–Weerdenburg 1980, 122–139; appointed in the sources as “the second after the Briant 1984, 69–80). -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

Ancient Persian Civilization

Ancient Persian Civilization Dr. Anousha Sedighi Associate Professor of Persian [email protected] Summer Institute: Global Education through film Middle East Studies Center Portland State University Students hear about Iran through media and in the political context → conflict with U.S. How much do we know about Iran? (people, places, events, etc.) How much do we know about Iran’s history? Why is it important to know about Iran’s history? It helps us put today’s conflicts into context: o 1953 CIA coup (overthrow of the first democratically elected Prime Minister: Mossadegh) o Hostage crisis (1979-1981) Today we learn about: Zoroastrianism (early monotheistic religion, roots in Judaism, Christianity, Islam) Cyrus the great (founder of Persian empire, first declaration of human rights) Foreign invasions of Persia (Alexander, Arab invasion, etc.) Prominent historical figures (Ferdowsi, Avicenna, Rumi, Razi, Khayyam, Mossadegh, Artemisia, etc.) Sounds interesting! Do we have educations films about them? Yes, in fact most of them are available online! Zoroaster Zoroaster: religious leader Eastern Iran, exact birth/time not certain Varies between 6000-1000 BC Promotes peace, goodness, love for nature Creator: Ahura-Mazda Three principles: Good thoughts Good words Good deeds Influenced Judaism, Christianity, Islam Ancient Iranian Peoples nd Middle of 2 melluniuem (Nomadic people) Aryan → Indo European tribe → Indo-Iranian Migrated to Iranian Plateau (from Eurasian plains) (Persians, Medes, Scythians, Bactrians, Parthians, Sarmatians, -

Democracy and Empire in Greek Antiquity

This course will explore the history, culture, and art of post- classical Greek antiquity, focusing on the period between two of the most studied and renowned figures of the ancient world: Alexander the Great and Cleopatra VII. We will learn and analyze how the ancient world changed with Alexander and his successors, emphasizing the political, social, and cultural transformations; changes in the religious landscape; and formation of the state. We will also discuss the legacy of the Hellenistic world as an integral part of our intellectual heritage. Developments in Athenian Democracy DRACONIAN Laws (DRACO)7th c BCE strict laws enforcing aristocratic rule- there was only one penalty prescribed, death, for every crime from murder down to loitering (see Plut. Sol. 17.1). - the new Constitution gave political rights to those Athenians “who bore arms,” those Athenians wealthy enough to afford the bronze armor and weapons of a hoplite. CRISIS- 1) Tensions among aristocrats- 2) Poor citizens, in years of poor harvests, had to mortgage portions of their land to wealthier citizens in exchange for food and seed to plant. They became more vulnerable to subsequent hardships (see Aristot. Ath. Pol. 2.1-2). SOLON- 6th c. SOLONIAN LAWS they did not establish a democracy as radical as what would follow He took steps to alleviate the crisis of debt that the poor suffered He abolished the practice of giving loans with a citizen’s freedom as collateral He gave every Athenian the right to appeal to a jury, thus taking ultimate authority for interpreting the law out of the hands of the Nine Archons (remnant of aristocracy) and putting it in the hands of a more democratic body, since any citizen could serve on a jury. -

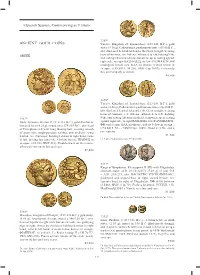

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30Am ANCIENT GOLD COINS

Eleventh Session, Commencing at 9.30am 3389* ANCIENT GOLD COINS Thrace, Kingdom of, Lysimachos, (323-281 B.C.), gold stater, (8.36 g), Callatis mint, posthumous issue c.88-86 B.C., obv. diademed head of Alexander the Great to right, wearing GREEK horn of Ammon, rev. Athena enthroned to left, holding Nike and resting left arm on shield, transverse spear resting against right side, to right ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩ[Σ], to left ΛΥΣΙΜΑΧΟΥ, HP monogram below arm, ΚΑΛ on throne, trident below in exergue, (cf.S.6813, M.266, SNG Cop.1089). Extremely fi ne and virtually as struck. $4,500 3390* Thrace, Kingdom of, Lysimachos, (323-281 B.C.), gold stater, (8.26 g), Callatis mint, posthumous issue c.88-86 B.C., obv. diademed head of Alexander the Great to right, wearing horn of Ammon, rev. Athena enthroned to left, holding 3387* Nike and resting left arm on shield, transverse spear resting Sicily, Syracuse, Hieron II, (275-215 B.C.), gold drachm or against right side, to right ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ, to left ΛΥΣΙΜΑΧΟΥ, hundred litrai (4.25 g), struck circa 275-263 B.C., obv. head ΦΜ under arm, ΚΑΛ on throne, trident below in exergue, of Persephone left with long fl owing hair, wearing wreath (cf.S.6813, M.-, cf.SNG Cop. 1089). Good very fi ne and a of grain ears, single-pendant earring, and necklace, wing rare variety. behind, rev. charioteer, holding kentron in right hand, reins $1,300 in left, driving fast biga left, A below horses, ΙΕΡΩΝΟΣ in Ex Noble Numismatics Sale 79 (lot 3208). -

The Contest for Macedon

The Contest for Macedon: A Study on the Conflict Between Cassander and Polyperchon (319 – 308 B.C.). Evan Pitt B.A. (Hons. I). Grad. Dip. This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Tasmania October 2016 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does this thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Evan Pitt 27/10/2016 ii Acknowledgements A doctoral dissertation is never completed alone, and I am forever grateful to my supervisor, mentor and friend, Dr Graeme Miles, who has unfailingly encouraged and supported me over the many years. I am also thankful to all members of staff at the University of Tasmania; especially to the members of the Classics Department, Dr Jonathan Wallis for putting up with my constant stream of questions with kindness and good grace and Dr Jayne Knight for her encouragement and support during the final stages of my candidature. The concept of this thesis was from my honours project in 2011. Dr Lara O’Sullivan from the University of Western Australia identified the potential for further academic investigation in this area; I sincerely thank her for the helpful comments and hope this work goes some way to fulfil the potential she saw. -

The Anabasis of Alexander; Or, the History of the Wars and Conquests Of

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library PA 3935.E5A3 1884 Anabasis of Alexander: or. The history o 3 1924 026 460 752 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026460752 THE ANABASIS OF ALEXANDER. THE ANABASIS OF ALEXANDER; OR, i^e Pislorg of tl^e ffiars anir Cottqnjcsts of '^hxmhtx tl^t (irtat. LITERALLY TRANSLATED, WITH A COMMENTARY, FROM THE GREEK OF ARRIAN THE NICOMEDIAN, BY E. J. CHINNOCK, M.A., LL.B., L0ND9N, Rector of Dumfries Academy. HODDER AND STOUGHTON, 27, PATERNOSTER ROW. MDCCCLXXXIV. "g 5~ /\ . 5"b r. f ^5- A3 Butler & Tanner. The Selwood Fiintiug Works, Frome, and London. PREFACE. When I began this Translation^ more than two years ago, I had no intention of publishing it; but as the work progressed, it occurred to me that Arrian is an Author deserving of more attention from the English- speaking races than he has yet received. No edition of his works has, so far as I am aware, ever appeared in England, though on the Continent many have been pub- lished. In the following Translation I have tried to give as literal a rendering of the Greek text as I could with- out transgressing the idioms of our own language. My theory of the duty of a Translator is, to give the ipsissima verba of his Author as nearly as possible, and not put into his mouth words which he never used, under the mistaken notion of improving his diction or his way of stating his case.