Economic and Social Impact Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal and Indigenous Languages; a Language Other Than English for All; and Equitable and Widespread Language Services

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 355 819 FL 021 087 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph TITLE The National Policy on Languages, December 1987-March 1990. Report to the Minister for Employment, Education and Training. INSTITUTION Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education, Canberra. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 152p. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Advisory Committees; Agency Role; *Educational Policy; English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Language Role; *National Programs; Program Evaluation; Program Implementation; *Public Policy; *Second Languages IDENTIFIERS *Australia ABSTRACT The report proviCes a detailed overview of implementation of the first stage of Australia's National Policy on Languages (NPL), evaluates the effectiveness of NPL programs, presents a case for NPL extension to a second term, and identifies directions and priorities for NPL program activity until the end of 1994-95. It is argued that the NPL is an essential element in the Australian government's commitment to economic growth, social justice, quality of life, and a constructive international role. Four principles frame the policy: English for all residents; support for Aboriginal and indigenous languages; a language other than English for all; and equitable and widespread language services. The report presents background information on development of the NPL, describes component programs, outlines the role of the Australian Advisory Council on Languages and Multicultural Education (AACLAME) in this and other areas of effort, reviews and evaluates NPL programs, and discusses directions and priorities for the future, including recommendations for development in each of the four principle areas. Additional notes on funding and activities of component programs and AACLAME and responses by state and commonwealth agencies with an interest in language policy issues to the report's recommendations are appended. -

Than One Way to Catch a Frog: a Study of Children's

More than one way to catch a frog: A study of children’s discourse in an Australian contact language Samantha Disbray Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Linguistics and Applied Linguistics University of Melbourne December, 2008 Declaration This is to certify that: a. this thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD b. due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all material used c. the text is less than 100,000 words, exclusive of tables, figures, maps, examples, appendices and bibliography ____________________________ Samantha Disbray Abstract Children everywhere learn to tell stories. One important aspect of story telling is the way characters are introduced and then moved through the story. Telling a story to a naïve listener places varied demands on a speaker. As the story plot develops, the speaker must set and re-set these parameters for referring to characters, as well as the temporal and spatial parameters of the story. To these cognitive and linguistic tasks is the added social and pragmatic task of monitoring the knowledge and attention states of their listener. The speaker must ensure that the listener can identify the characters, and so must anticipate their listener’s knowledge and on-going mental image of the story. How speakers do this depends on cultural conventions and on the resources of the language(s) they speak. For the child speaker the development narrative competence involves an integration, on-line, of a number of skills, some of which are not fully established until the later childhood years. -

Ali Curung CDEP

The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities: Support document JOSIE MISKO This document was produced by the author(s) based on their research for the report, The role of Community Development Employment Projects in rural and remote communities, and is an added resource for further information. The report is available on NCVER’s website: <http://www.ncver.edu.au> The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author(s). SUPPORT DOCUMENT e Need more information on vocational education and training? Visit NCVER’s website <http://www.ncver.edu.au> 4 Access the latest research and statistics 4 Download reports in full or in summary 4 Purchase hard copy reports 4 Search VOCED—a free international VET research database 4 Catch the latest news on releases and events 4 Access links to related sites Contents Contents 3 Regional Council – Roma 4 Regional Council – Tennant Creek 7 Ali Curung CDEP 9 Bidjara-Charleville CDEP 16 Cherbourg CDEP 21 Elliot CDEP 25 Julalikari CDEP 30 Julalikari-Buramana CDEP 33 Kamilaroi – St George CDEP 38 Papulu Apparr-Kari CDEP 42 Toowoomba CDEP 47 Thangkenharenge – Barrow Creek CDEP 51 Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education (2002) 53 Institute of Aboriginal Development 57 Julalikari RTO 59 NCVER 3 Regional Council – Roma Regional needs Members of the regional council agreed that the Indigenous communities in the region required people to acquire all the skills and knowledge that people in mainstream communities required. -

Contents What’S New

July / August, No. 4/2011 CONTENTS WHAT’S NEW Quandamooka Native Title Determination ............................... 2 Win a free registration to the Joint Management Workshop at the 2011 National Native 2012 Native Title Conference! Title Conference: ‘What helps? What harms?’ ........................ 4 Just take 5 minutes to complete our An extract from Mabo in the Courts: Islander Tradition to publications survey and you will go into the Native Title: A Memoir ............................................................... 5 draw to win a free registration to the 2012 QLD Regional PBC Meeting ...................................................... 6 Native Title Conference. Those who have What’s New ................................................................................. 6 already completed the survey will be automatically included. Recent Cases ............................................................................. 6 Legislation and Policy ............................................................. 12 Complete the survey at: Native Title Publications ......................................................... 13 http://www.tfaforms.com/208207 Native Title in the News ........................................................... 14 If you have any questions or concerns, please Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) ........................... 20 contact Matt O’Rourke at the Native Title Research Unit on (02) 6246 1158 or Determinations ......................................................................... 21 [email protected] -

Loanwords Between the Arandic Languages and Their Western Neighbours: Principles of Identification and Phonological Adaptation

Loanwords between the Arandic languages and their western neighbours: Principles of identification and phonological adaptation Harold%Koch% Australian%National%University% [email protected]% This paper 1 summarises the characteristics of loanwords, especially the ways in which they are adapted to the structure of the borrowing language, and surveys the various tests that have been provided in both the general historical linguistics literature and Australianist literature for identifying the fact and direction of borrowing. It then provides a case study of loanwords out of and into the Arandic languages; the other languages involved are especially Warlpiri but to some extent dialects of the Western Desert language. The primary focus is on the phonological adaptation of loanwords between languages whose phonological structure differs especially in the presence vs. absence of initial consonants, in consequence of earlier changes whereby Arandic languages lost all initial consonants. While loanwords out of Arandic add a consonant, it is claimed that loanwords into Arandic include two chronological strata: in one the source consonant was preserved but the other (older) pattern involved truncation of the source consonant. Reasons for this twofold behaviour are presented (in terms of diachronic and contrastive phonology), and the examples of the more radical (older) pattern 1 The title, abstract, and introduction have been altered from the version offered at ALS2013, which was titled ‘How to identify loanwords between Australian languages: -

Utopia (Urapuntja)

Central Australia Region Community Profile Utopia (Urapuntja) 1st edition September 2009 Funded by the Australian Government This Community Profile provides you with information specific to the Alywarra-Anmatjere Region of the Northern Territory. The information has been compiled though a number of text and internet resources, and consultations with members of the local communities. The first version of this Community Profile was prepared for RAHC by The Echidna Group and we acknowledge and thank Dr Terri Farrelly and Ms Bronwyn Lumby for their contribution. Other sources include: http://www.teaching.nt.gov.au/remote_schools/utopia.html http://www.utopianaboriginalart.com.au/about_us/about_us.php http://www.gpnnt.org.au/client_images/209836.pdf RAHC would also like to acknowledge and express gratitude to the Aboriginal people of the Alywarra-Anmatjere Region who have so generously shared aspects of their culture and communities for use in this Profile. *Please note: The information provided in this community profile is correct, to the best of RAHC’s knowledge, at the time of printing. This community profile will be regularly updated as new information comes to hand. If you have any further information about this community that would be useful to add to this profile please contact RAHC via: [email protected] or call 1300 MYRAHC. Photographs used in this Community Profile are copyright of the Remote Area Health Corps. Permission was sought from all individuals or guardians of individuals, before photography commenced. © Copyright — Remote Area Health Corps, 2009 2 The Northern Territory This map of the Northern Territory, divided into regions, has been adapted from the Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (OATSIH) Program Management & Implementation Section (2008) Map of the Northern Territory. -

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: a Case Study of the Granites Mine

Building an Implementation Framework for Agreements with Aboriginal Landowners: A Case Study of The Granites Mine Rodger Donald Barnes BSc (Geol, Geog) Hons James Cook University A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Architecture Abstract This thesis addresses the important issue of implementation of agreements between Aboriginal people and mining companies. The primary aim is to contribute to developing a framework for considering implementation of agreements by examining how outcomes vary according to the processes and techniques of implementation. The research explores some of the key factors affecting the outcomes of agreements through a single case study of The Granites Agreement between Newmont Mining Corporation and traditional Aboriginal landowners made under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (NT) 1976. This is a fine-grained longitudinal study of the origins and operation of the mining agreement over a 28-year period from its inception in 1983 to 2011. A study of such depth and scope of a single mining agreement between Aboriginal people and miners has not previously been undertaken. The history of The Granites from the first European contact with Aboriginal people is compiled, which sets the study of the Agreement in the context of the continued adaption by Warlpiri people to European colonisation. The examination of the origins and negotiations of the Agreement demonstrates the way very disparate interests between Aboriginal people, government and the mining company were reconciled. A range of political agendas intersected in the course of making the Agreement which created an extremely complex and challenging environment not only for negotiations but also for managing the Agreement once it was signed. -

How Warumungu People Express New Concepts Jane Simpson Tennant

How Warumungu people express new concepts Jane Simpson Tennant Creek 16/10/85 [This paper appeared in a lamentedly defunct journal: Simpson, Jane. 1985. How Warumungu people express new concepts. Language in Central Australia 4:12-25.] I. Introduction Warumungu is a language spoken around Tennant Creek (1). It is spoken at Rockhampton Downs and Alroy Downs in the east, as far north as Elliott, and as far south as Ali Curung. Neighbouring languages include Alyawarra, Kaytej, Jingili, Mudbura, Wakaya, Wampaya, Warlmanpa and Warlpiri. In the past, many of these groups met together for ceremonies and trade. There were also marriages between people of different language groups. People were promised to 'close family' from close countries. Many children would grow up with parents who could speak different languages. This still happens, and therefore many people are multi-lingual - they speak several languages. This often results in multi-lingual conversation. Sometimes one person will carry on their side of the conversation in Warumungu, while the other person talks only in Warlmanpa. Other times a person will use English, Warumungu, Alyawarra, Warlmanpa, and Warlpiri in a conversation, especially if different people take part in it. The close contact between speakers of different languages shows in shared words. For example, many words for family-terms are shared by different languages. As Valda Napururla Shannon points out, Eastern Warlpiri ("wakirti" Warlpiri (1)) shares words with its neighbours, Warumungu and Warlmanpa, while Western Warlpiri shares words with its neighbours. Pintupi, Gurindji, Anmatyerre etc. In Eastern Warlpiri, Warlmanpa and Warumungu the word "kangkuya" is used for 'father's father' (or 'father's father's brother' or 'father's father's sister'). -

Critical Australian Indigenous Histories

Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Transgressions critical Australian Indigenous histories Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah (editors) Published by ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Monograph 16 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Transgressions [electronic resource] : critical Australian Indigenous histories / editors, Ingereth Macfarlane ; Mark Hannah. Publisher: Acton, A.C.T. : ANU E Press, 2007. ISBN: 9781921313448 (pbk.) 9781921313431 (online) Series: Aboriginal history monograph Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Indigenous peoples–Australia–History. Aboriginal Australians, Treatment of–History. Colonies in literature. Australia–Colonization–History. Australia–Historiography. Other Authors: Macfarlane, Ingereth. Hannah, Mark. Dewey Number: 994 Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Rob Paton (Treasurer/Public Officer), Ingereth Macfarlane (Secretary/ Managing Editor), Richard Baker, Gordon Briscoe, Ann Curthoys, Brian Egloff, Geoff Gray, Niel Gunson, Christine Hansen, Luise Hercus, David Johnston, Steven Kinnane, Harold Koch, Isabel McBryde, Ann McGrath, Frances Peters- Little, Kaye Price, Deborah Bird Rose, Peter Radoll, Tiffany Shellam Editors Ingereth Macfarlane and Mark Hannah Copy Editors Geoff Hunt and Bernadette Hince Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to Aboriginal History, Box 2837 GPO Canberra, 2601, Australia. Sales and orders for journals and monographs, and journal subscriptions: T Boekel, email: [email protected], tel or fax: +61 2 6230 7054 www.aboriginalhistory.org ANU E Press All correspondence should be addressed to: ANU E Press, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected], http://epress.anu.edu.au Aboriginal History Inc. -

Ready Programs and the Papulu CLC Director David Ross

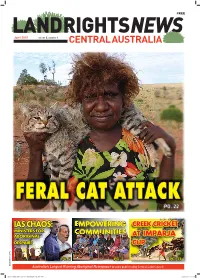

FREE April 2015 VOLUME 5. NUMBER 1. PG. ## FERAL CAT ATTACK PG. 22 IAS CHAOS: EMPOWERING CREEK CRICKET MINISTERS FOR COMMUNITIES ABORIGINAL AT IMPARJA DESPAIR? CUP PG. 2 PG. 2 PG. 33 ISSN 1839-5279 59610 CentralLandCouncil CLC Newspaper 36pp Alts1.indd 1 10/04/2015 12:32 pm NEWS Aboriginal Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion confronts an EDITORIAL angry crowd at the Alice Springs Convention Centre. Land Rights News Central He said organisations got the funding they deserved. Australia is published by the Central Land Council three times a year. The Central Land Council 27 Stuart Hwy Alice Springs NT 0870 tel: 89516211 www.clc.org.au email [email protected] Contributions are welcome SUBSCRIPTIONS Land Rights News Central Australia subscriptions are $20 per year. LRNCA is distributed free to Aboriginal organisations and communities in Central Australia Photo courtesy CAAMA To subscribe email: [email protected] IAS chaos sparks ADVERTISING Advertise in the only protests and probe newspaper to reach Aboriginal people THE AUSTRALIAN Senate will inquire original workers. Neighbouring Barkly Regional Council re- into the delayed and chaotic funding round Nearly half of the 33 organisations sur- ported 26 Aboriginal job losses as a result of in remote Central of the new Indigenous advancement scheme veyed by the Alice Springs Chamber of Com- a 35% funding cut to community services in a (IAS), which has done as much for the PM’s merce were offered less funding than they had UHJLRQWURXEOHGE\SHWUROVQLI¿QJ Australia. reputation in Aboriginal Australia as his way previously for ongoing projects. President Barb Shaw told the Tennant with words. -

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No. 116/15cncl TO: ORDINARY COUNCIL – 31 AUGUST 2015 SUBJECT: MAYOR’S REPORT 1. MEETINGS AND APPOINTMENTS 1.1 Robert Sommerville; Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education, Mike Crow and Peter Solly 1.2 Alice Springs Masters Games Advisory Committee 1.3 Department of Chief Minister – Scott Lovett 1.4 Rachel and Barb Satour – Rate Payers 1.5 Clontarf - Scott Allen, Greg Buxton & Ian McAdam 1.6 CEOs, Mayors & Presidents Forum, Darwin, The Hon Bess Price, Minister for Local Government and Community Services 1.7 Northern Territory Grants Commission – Peter Thornton 1.8 Post National General Assembly Board Meeting Teleconference 1.9 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Brendan Heenan, Cr Eli Melky 1.10 ALGA/Federal Assistance Grants Campaign Steering Committee 1.11 Western Australian Local Government Association Conference, Perth 1.12 Jimmy Cocking ALEC 1.13 Tony Tapsell CEO LGANT 1.14 Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet; Ren Kelly and Trish Johnston Acting Regional Manager 1.15 Tegan Copland - St Phillips College, School assignment 1.16 Hannah Millerick & Chloe Erlich – NT Events Photography 1.17 Alice Springs Accommodation Action Group 1.18 Road Transport Hall of Fame – Meeting re Reunion 2015 1.19 The Hon Robyn Lambley MLA 1.20 Mt Isa to Tennant Creek Pipeline Briefing – Paul Malony, APA Group 1.21 Deputy Mayor Steve Brown, Cr Eli Melky, CEO Rex Mooney 1.22 Debbie Staines - Clarity NT 1.23 Department of Chief Minister, Todd Mall Pop Up Shops 1.24 Athletics’ meeting – Mayor Damien Ryan, Deputy Mayor -

A Grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal Language of the Northern Territory

A grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory Pensalfini, R. A grammar of Jingulu, an Aboriginal language of the Northern Territory. PL-536, xix + 262 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2003. DOI:10.15144/PL-536.cover ©2003 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics John Bowden, 2001, Taba: description of a South Halmahera Austronesian language. Mark Harvey, 2001, A grammar of Limilngan: a language of the Mary River Region, Northern Territory, Allstralia. Margaret Mutu with Ben Telkitutoua, 2002, Ua Pou: aspects of a Marquesan dialect. Elisabeth Patz, 2002, A grammar of the Kukll Yalanji language of north Queensland. Angela Terrill, 2002, Dharumbal: the language of Rockhampton, Australia. Catharina Williams-van Klinken, John Hajek and Rachel Nordlinger, 2002, Tetlin Dili: a grammar of an East Timorese language. Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Shldies at the Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the school's Department of Linguistics. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board.