Our Planets at a Glance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUICE Red Book

ESA/SRE(2014)1 September 2014 JUICE JUpiter ICy moons Explorer Exploring the emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants Definition Study Report European Space Agency 1 This page left intentionally blank 2 Mission Description Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer Key science goals The emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants Characterise Ganymede, Europa and Callisto as planetary objects and potential habitats Explore the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giants Payload Ten instruments Laser Altimeter Radio Science Experiment Ice Penetrating Radar Visible-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging Spectrometer Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph Imaging System Magnetometer Particle Package Submillimetre Wave Instrument Radio and Plasma Wave Instrument Overall mission profile 06/2022 - Launch by Ariane-5 ECA + EVEE Cruise 01/2030 - Jupiter orbit insertion Jupiter tour Transfer to Callisto (11 months) Europa phase: 2 Europa and 3 Callisto flybys (1 month) Jupiter High Latitude Phase: 9 Callisto flybys (9 months) Transfer to Ganymede (11 months) 09/2032 – Ganymede orbit insertion Ganymede tour Elliptical and high altitude circular phases (5 months) Low altitude (500 km) circular orbit (4 months) 06/2033 – End of nominal mission Spacecraft 3-axis stabilised Power: solar panels: ~900 W HGA: ~3 m, body fixed X and Ka bands Downlink ≥ 1.4 Gbit/day High Δv capability (2700 m/s) Radiation tolerance: 50 krad at equipment level Dry mass: ~1800 kg Ground TM stations ESTRAC network Key mission drivers Radiation tolerance and technology Power budget and solar arrays challenges Mass budget Responsibilities ESA: manufacturing, launch, operations of the spacecraft and data archiving PI Teams: science payload provision, operations, and data analysis 3 Foreword The JUICE (JUpiter ICy moon Explorer) mission, selected by ESA in May 2012 to be the first large mission within the Cosmic Vision Program 2015–2025, will provide the most comprehensive exploration to date of the Jovian system in all its complexity, with particular emphasis on Ganymede as a planetary body and potential habitat. -

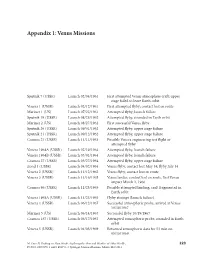

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

Planetary Rings

CLBE001-ESS2E November 10, 2006 21:56 100-C 25-C 50-C 75-C C+M 50-C+M C+Y 50-C+Y M+Y 50-M+Y 100-M 25-M 50-M 75-M 100-Y 25-Y 50-Y 75-Y 100-K 25-K 25-19-19 50-K 50-40-40 75-K 75-64-64 Planetary Rings Carolyn C. Porco Space Science Institute Boulder, Colorado Douglas P. Hamilton University of Maryland College Park, Maryland CHAPTER 27 1. Introduction 5. Ring Origins 2. Sources of Information 6. Prospects for the Future 3. Overview of Ring Structure Bibliography 4. Ring Processes 1. Introduction houses, from coalescing under their own gravity into larger bodies. Rings are arranged around planets in strikingly dif- Planetary rings are those strikingly flat and circular ap- ferent ways despite the similar underlying physical pro- pendages embracing all the giant planets in the outer Solar cesses that govern them. Gravitational tugs from satellites System: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Like their account for some of the structure of densely-packed mas- cousins, the spiral galaxies, they are formed of many bod- sive rings [see Solar System Dynamics: Regular and ies, independently orbiting in a central gravitational field. Chaotic Motion], while nongravitational effects, includ- Rings also share many characteristics with, and offer in- ing solar radiation pressure and electromagnetic forces, valuable insights into, flattened systems of gas and collid- dominate the dynamics of the fainter and more diffuse dusty ing debris that ultimately form solar systems. Ring systems rings. Spacecraft flybys of all of the giant planets and, more are accessible laboratories capable of providing clues about recently, orbiters at Jupiter and Saturn, have revolutionized processes important in these circumstellar disks, structures our understanding of planetary rings. -

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center ......213 Publisher’s Note ......................................................... vii Chandra X-Ray Observatory ....................................223 Introduction ................................................................. ix Clementine Mission to the Moon .............................229 Preface to the Third Edition ..................................... xiii Commercial Crewed vehicles ..................................235 Contributors ............................................................. xvii Compton Gamma Ray Observatory .........................240 List of Abbreviations ................................................. xxi Cooperation in Space: U.S. and Russian .................247 Complete List of Contents .................................... xxxiii Dawn Mission ..........................................................254 Deep Impact .............................................................259 Air Traffic Control Satellites ........................................1 Deep Space Network ................................................264 Amateur Radio Satellites .............................................6 Delta Launch Vehicles .............................................271 Ames Research Center ...............................................12 Dynamics Explorers .................................................279 Ansari X Prize ............................................................19 Early-Warning Satellites ..........................................284 -

Planetary Exploration : Progress and Promise

PLANET ARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENTS: NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS: SIGNIFICANT EVENTS PLANETARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS-1978 NASA SPACE SCIENCE PROGRAM FUNDING: 5 -YEAR PLAN NASA OSS 5-YEAR PLAN: PLANETARY PROGRAM FUNDING REFERENCE COP'I PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist Lunar and Planetary Institute 3303 NASA Road One Houston, Texas 77058 Lunar and Planetary Institute Contribution No. 297 (June 1978 update> NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS SIGNIFICANT EVENTS MISSION EVENTS PIONEER VENUS ORBITER ORBIT INSERTION, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER VENUS MULTIPROBE VENUS ENCOUNTER/ENTRY, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER 11 SATURN ENCOUNTER, SEPTEMBER 1979 VOYAGER 1 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, MARCH 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1980 VOYAGER 2 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, JULY 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, AUGUST 1981 URANUS ENCOUNTER, JANUARY 1986 SOLAR MAXIMUM MISSION LAUNCH, OCTOBER 1979 VENUS ORBITAL IMAGING RADAR VENUS ENCOUNTER, SPRING 1985 SOLAR POLAR MISSION JUPITER ENCOUNTER, 1984 SOLAR POLES PASSAGE, 1986 GALILEO MISSION MARS FLYBY, APRIL 1982 JUPITER ENCOUNTER (ORBIT INSERTION/ PROBE ENTRY), 1985 COMET HALLEYlTEMPEL, . 2'J MISSION• HALLEY ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1985 TEMPEL 2 ENCOUNTER, JULY 1988 or COMET ENCKE RENDEZVOUS ENCKE ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS GEOCHEMICAL ORBITER MARS ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS SAMPLE RETURN MARS ENCOUNTER, 1989 EARTH RETURN, 1991 SATURN ORBITER DUAL PROBE SATURN ENCOUNTER, 1992 from NASA Headquarters 5-year plan May 1978 PLANETARY EXPLORATION -- PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENT S: Planetary exploration progress - 1977 fig. 1 The future fig. 2 Inner planets plan fig. 3 Outer planets plan fig. 4 Small bodies plan fig. 5 compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE 3303 NASA Road One Houston, TX 77058 September 1977 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE CONTRIBUTION No. -

Venus Exploration Opportunities Within NASA's Solar System Exploration Roadmap

Venus Exploration Opportunities within NASA's Solar System Exploration Roadmap by Tibor Balint1, Thomas Thompson1, James Cutts1 and James Robinson2 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Caltech 2NASA HQ Presented at the Venus Entry Probe Workshop European Space Agency (ESA) European Space and Technology Centre (ESTEC) The Netherlands January 19-20, 2006 By Tibor Balint, JPL, November 8, 2005 Balint, JPL, November Tibor By 1 Acknowledgments • Solar System Exploration Road Map Team • NASA HQ – Ellen Stofan – James Robinson –Ajay Misra • Planetary Program Support Team – Steve Saunders – Adriana Ocampoa – James Cutts – Tommy Thompson • VEXAG Science Team – Tibor Balint – Sushil Atreya (U of Michigan) – Craig Peterson – Steve Mackwell (LPI) – Andrea Belz – Martha Gilmore (Wesleyan University) – Elizabeth Kolawa – Michael Pauken – Alexey Pankine (Global Aerospace Corp) – Sanjay Limaye (University of Wisconsin-Madison) • High Temperature Balloon Team – Kevin Baines (JPL) – Jeffery L. Hall – Bruce Banerdt (JPL) – Andre Yavrouian – Ellen Stofan (Proxemy Research, Inc.) – Jack Jones – Viktor Kerzhanovich Other JPL candidates – Suzanne Smrekar (JPL) • Radioisotope Power Systems Study Team – Dave Crisp (JPL) – Jacklyn Green Astrobiology – Bill Nesmith – David Grinspoon (University of Colorado) – Rao Surampudi – Adam Loverro By Tibor Balint, JPL, November 8, 2005 Balint, JPL, November Tibor By 2 Overview • Brief Summary of Past Venus In-situ Missions • Recent Solar System Exploration Strategic Plans • Potential Future Venus Exploration Missions • New Technology -

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

NASA and Planetary Exploration

**EU5 Chap 2(263-300) 2/20/03 1:16 PM Page 263 Chapter Two NASA and Planetary Exploration by Amy Paige Snyder Prelude to NASA’s Planetary Exploration Program Four and a half billion years ago, a rotating cloud of gaseous and dusty material on the fringes of the Milky Way galaxy flattened into a disk, forming a star from the inner- most matter. Collisions among dust particles orbiting the newly-formed star, which humans call the Sun, formed kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals which in turn aggregated to form the present-day planets.1 On the third planet from the Sun, several billions of years of evolution gave rise to a species of living beings equipped with the intel- lectual capacity to speculate about the nature of the heavens above them. Long before the era of interplanetary travel using robotic spacecraft, Greeks observing the night skies with their eyes alone noticed that five objects above failed to move with the other pinpoints of light, and thus named them planets, for “wan- derers.”2 For the next six thousand years, humans living in regions of the Mediterranean and Europe strove to make sense of the physical characteristics of the enigmatic planets.3 Building on the work of the Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Hellenistic Greeks who had developed mathematical methods to predict planetary motion, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria put forth a theory in the second century A.D. that the planets moved in small circles, or epicycles, around a larger circle centered on Earth.4 Only partially explaining the planets’ motions, this theory dominated until Nicolaus Copernicus of present-day Poland became dissatisfied with the inadequacies of epicycle theory in the mid-sixteenth century; a more logical explanation of the observed motions, he found, was to consider the Sun the pivot of planetary orbits.5 1. -

The Science Return from Venus Express the Science Return From

The Science Return from Venus Express Venus Express Science Håkan Svedhem & Olivier Witasse Research and Scientific Support Department, ESA Directorate of Scientific Programmes, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands Dmitri V. Titov Max Planck Institute for Solar System Studies, Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany (on leave from IKI, Moscow) ince the beginning of the space era, Venus has been an attractive target for Splanetary scientists. Our nearest planetary neighbour and, in size at least, the Earth’s twin sister, Venus was expected to be very similar to our planet. However, the first phase of Venus spacecraft exploration (1962-1985) discovered an entirely different, exotic world hidden behind a curtain of dense cloud. The earlier exploration of Venus included a set of Soviet orbiters and descent probes, the Veneras 4 to14, the US Pioneer Venus mission, the Soviet Vega balloons and the Venera 15, 16 and Magellan radar-mapping orbiters, the Galileo and Cassini flybys, and a variety of ground-based observations. But despite all of this exploration by more than 20 spacecraft, the so-called ‘morning star’ remains a mysterious world! Introduction All of these earlier studies of Venus have given us a basic knowledge of the conditions prevailing on the planet, but have generated many more questions than they have answered concerning its atmospheric composition, chemistry, structure, dynamics, surface-atmosphere interactions, atmospheric and geological evolution, and plasma environment. It is now high time that we proceed from the discovery phase to a thorough -

Mission Overview the Pioneer Mission Set the Stage for U.S. Space

Mission Overview The Pioneer mission set the stage for U.S. space exploration. Pioneer 1 was the first manmade object to escape the Earth's gravitational field. Later Pioneer 4 was the first spacecraft to fly to the moon, Pioneer 10 was the first to Jupiter, Pioneer 11 was the first to Saturn and Pioneer 12 was the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit another planet, Venus. The following table summarizes the Pioneer spacecraft and scientific objectives of the Pioneer mission. Name Launch Mission Status (as of 1998) ----------------------------------------------------------------- Pioneer 1 1958-10-11 Moon Reached altitude of 72765 miles Pioneer 2 1958-11-08 Moon Reached altitude of 963 miles Pioneer 3 1958-12-02 Moon Reached altitude of 63580 miles Pioneer 4 1959-03-03 Moon Passed by moon into solar orbit Pioneer 5 1960-03-11 Solar Orbit Entered solar orbit Pioneer 6 1965-12-16 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 7 1966-08-17 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 8 1967-12-13 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 9 1967-11-08 Solar Orbit Signal lost in 1983 Pioneer E 1969-08-07 Solar Orbit Launch failure Pioneer10 1972-03-02 Jupiter Communication terminated 1998 Pioneer11 1972-03-02 Jupiter/Saturn Communication terminated 1997 Pioneer12 1978-05-20 Venus Entered Venus atmos. 1992-10-08 The focus of this document is on Pioneer Venus (12), the last spacecraft in a mission of firsts in space exploration. Probe Separation: Pioneer Venus separated into two spacecraft on Aug 8, 1978: an Orbiter (PVO) and a Multiprobe. The latter was separated into five separate vehicles near Venus. -

Pioneer Venus Multiprobe Entry Telemetry Recovery

TDA Progress Report 42-57 March and April 1980 Pioneer Venus Multiprobe Entry Telemetry Recovery R. B. Miller TDA Mission Support and R. Ramos Ames Research Center The Entry Phase of the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe Mission involved data transmission over only a two-hour span. The criticality of recovery of those two hours of data, coupled with the fact that there were no radio signals from the Probes until their arrival at Venus, dictated unique telemetry recovery approaches on the ground. The result was double redundancy, use of spectrum analyzers to aid in rapid acquisition of the signals; and development of a technique for recovery of telemetry data without the use of real-time coherent detection, which is normally employed by all other NASA planetary missions. I. Introduction ing telemetry data for deep space missions. See Refs. 1 and 2 Two aspects of the Pioneer Venus Multiprobe Mission for descriptions of the general problem of communications at dictated unique approaches to the telemetry recovery com interplanetary distances and the· techniques used for NASA pared to other NASA planetary missions: the number of planetary missions. The ground equipment ordinarily used for spacecraft that simultaneously transmitted data and the telemetry recovery in a deep-space mission will be briefly two-hour duration of one-chance prime data transmission. described for completeness and to develop the framework to Since the four Probes entered the Venusian atmosphere understand why a second method of telemetry recovery was essentially simultaneously, each of two large antenna ground felt to be necessary. stations that could view the entry had to be able to acquire the signal and recover the information content from four separate Fundamental to all deep space communications to date has spacecraft simultaneously.