Lunar and Planetary Information Bulletin, Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

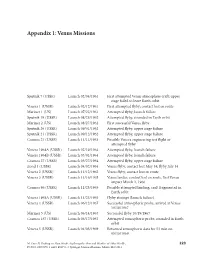

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report

NASA Technical Memorandum 84414 Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report Infrared Experiments Working Group NOVEMBER 1981 NASA NASA Technical Memorandum 84414 Infrared Experiments for Spaceborne Planetary Atmospheres Research Full Report Infrared Experiments Working Group Jet Propulsion Laboratory Pasadena, California NASA National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Branch 1981 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Summary of Principal Conclusions and Recommendations Chapter I The Role of Infrared Sensing in Atmospheric Science Chapter II Review of Existing Infrared Measurement Techniques Chapter III Critical Comparison of Proposed Measurement Techniques Chapter IV Conclusions and Recommended Instrument Developments Appendices: A Critical Technologies B Applicability of Atmospheric Infrared Instrumentation to Surface Science C Supporting Studies in Data Analysis and Numerical Modeling D Description of Planned Earth Orbital Platforms ii PREFACE Experiments conducted in the infrared spectral region provide a powerful tool for the study of the composition, structure and dynamics of planetary atmospheres. However, the field has become highly complex, especially that part associated with spacecraft sensing, and the range of technologies used so diverse that it is difficult to determine which of the available methods for making a particular measurement is to be preferred, even for those deeply involved in the field. Unfortunately, the realities of the age demand that some selectivity be employed; not all approaches can be supported. Furthermore, the chosen methods are generally sufficiently untried that long pre-flight developments are neces- sary if viable proposals are to be written for future flight opportunities. These considerations clearly lead to a program of developments which must be coordinated on a national scale. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

Complete List of Contents

Complete List of Contents Volume 1 Cape Canaveral and the Kennedy Space Center ......213 Publisher’s Note ......................................................... vii Chandra X-Ray Observatory ....................................223 Introduction ................................................................. ix Clementine Mission to the Moon .............................229 Preface to the Third Edition ..................................... xiii Commercial Crewed vehicles ..................................235 Contributors ............................................................. xvii Compton Gamma Ray Observatory .........................240 List of Abbreviations ................................................. xxi Cooperation in Space: U.S. and Russian .................247 Complete List of Contents .................................... xxxiii Dawn Mission ..........................................................254 Deep Impact .............................................................259 Air Traffic Control Satellites ........................................1 Deep Space Network ................................................264 Amateur Radio Satellites .............................................6 Delta Launch Vehicles .............................................271 Ames Research Center ...............................................12 Dynamics Explorers .................................................279 Ansari X Prize ............................................................19 Early-Warning Satellites ..........................................284 -

Galileo in 1610

Module 3 – Nautical Science Unit 4 – Astronomy Chapter 15 - The Planets Section 2 – Mars & Jupiter What You Will Learn to Do Demonstrate understanding of astronomy and how it pertains to our solar system and its related bodies: Moon, Sun, stars and planets Objectives 1. Describe the major features of Mars 2. Identify the principal characteristics of Jupiter Key Terms CPS Key Term Questions 1 - 5 Key Terms Nix Olympica - Snow of Olympus Galilean satellites - The four largest and brightest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto; discovered by Galileo in 1610 Prograde The counter-clockwise direction of motion - celestial bodies around the Sun as seen from above the north pole of the Sun; in the sky it is from west to east Key Terms Retrograde The clockwise direction of celestial motion - bodies around the Sun; in the sky it is from east to west Rotational axis - The straight line through all fixed points of a rotating rigid body around which all other points of the body move in circles Opening Question Discuss what types of exploration missions have occurred on Mars. (Use CPS “Pick a Student” for this question.) Mars Fourth from Mars the Sun and the next planet beyond Earth, Mars has aroused the greatest interest. Mars Mars Ares (Roman Mars) Mars Named for the Roman god of war, it is often called the “red planet.” Mars Mars’ red color and its rapid movement from west to east among the stars make it stand out in the sky. Mars Earth The best time to see Mars is when it is nearest to Earth in August and September, when the Earth is Sun between the Sun and Mars. -

Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon 440 Document II-1 Document Title

440 Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon Document II-1 Document Title: NASA, “ Minutes of Meeting of Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight,” 25–26 May 1959. Source: Folder 18675, NASA Historical Reference Collection, History Division, NASA Headquarters, Washington, DC. Within less than a year after its creation, NASA began looking at follow-on programs to Project Mercury, the initial human spacefl ight effort. A Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight was created in spring 1959; it consisted of top-level representatives of all of the NASA fi eld centers and NASA Headquarters. Harry J. Goett from Ames, but soon to be head of the newly created Goddard Space Flight Center, was named chair of the committee. The fi rst meeting of the committee took place on 25 and 26 May 1959, in Washington. Those in attendance provided an overview of research and thinking related to human spacefl ight at various NASA centers, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and the High Speed Flight Station (HSFS) at Edwards Air Force Base. George Low, then in charge of human spacefl ight at NASA Headquarters, argued for making a lunar landing NASA’s long-term goal. He was backed up by engineer and designer Maxime Faget of the Space Task Group of the Langley Research Center and Bruce Lundin of the Lewis Research Center. After further discussion at its June meeting, the Committee agreed on the lunar landing objective, and by the end of the year a lunar landing was incorporated into NASA’s 10-year plan as the long-range objective of the agency’s human spacefl ight program. -

Chapter 8 Did America’S Search for a “New Normal” Strike a Balance Between Individual (Freedoms And) Opportunities and National Security in the Postwar Years?

MI OPEN BOOK PROJECT UnitedReconstruction to Today States History Kimberly Eikenberry, Troy Kilgus, Adam Lincoln, Kim Noga, LaRissa Paras, Mark Radcliffe, Dustin Webb, Heather Wolf The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC-BY-NC-SA) license as part of Michigan’s participation in the national #GoOpen movement. This is version 1.4 of this resource, released August 2018 Information on the latest version and updates are available on the project homepage: http://textbooks.wmisd.org/dashboard.html ii Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA The Michigan Open Book About the Authors - United States History - Reconstruction - Today Project Kimberly Eikenberry Grand Haven High School Grand Haven Area Public Schools Kim has a B.A. in History and Social Studies and a M.A. in Educational Leadership, both from Project Manager: Dave Johnson, Wexford- Western Michigan University. She has served in many roles during her thirteen years as an Missaukee Intermediate School District educator, including department chair, curriculum director, and administrator. Kim currently teaches World History and Economics at Grand Haven High School. HS US Team Editor: Rebecca Bush, Ottawa Area Intermediate School District Authors Troy Kilgus Kimberly Eikenberry, Grand Haven Public Standish-Sterling Central High School Schools Standish-Sterling Community Schools Troy Kilgus serves as the high school social studies chair at Standish-Sterling Central High Troy Kilgus, Standish-Sterling Schools School. In his eight years of teaching, he has taught various social studies courses includ- ing AP US History and multiple levels of French. Mr. Kilgus earned his undergraduate de- Adam Lincoln, Ithaca Schools gree in French Education and his Masters in Teaching from Saginaw Valley State Univer- sity. -

The Power for Flight: NASA's Contributions To

The Power Power The forFlight NASA’s Contributions to Aircraft Propulsion for for Flight Jeremy R. Kinney ThePower for NASA’s Contributions to Aircraft Propulsion Flight Jeremy R. Kinney Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Kinney, Jeremy R., author. Title: The power for flight : NASA’s contributions to aircraft propulsion / Jeremy R. Kinney. Description: Washington, DC : National Aeronautics and Space Administration, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017027182 (print) | LCCN 2017028761 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626830387 (Epub) | ISBN 9781626830370 (hardcover) ) | ISBN 9781626830394 (softcover) Subjects: LCSH: United States. National Aeronautics and Space Administration– Research–History. | Airplanes–Jet propulsion–Research–United States– History. | Airplanes–Motors–Research–United States–History. Classification: LCC TL521.312 (ebook) | LCC TL521.312 .K47 2017 (print) | DDC 629.134/35072073–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017027182 Copyright © 2017 by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the United States Government or of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC Table of Contents Dedication v Acknowledgments vi Foreword vii Chapter 1: The NACA and Aircraft Propulsion, 1915–1958.................................1 Chapter 2: NASA Gets to Work, 1958–1975 ..................................................... 49 Chapter 3: The Shift Toward Commercial Aviation, 1966–1975 ...................... 73 Chapter 4: The Quest for Propulsive Efficiency, 1976–1989 ......................... 103 Chapter 5: Propulsion Control Enters the Computer Era, 1976–1998 ........... 139 Chapter 6: Transiting to a New Century, 1990–2008 .................................... -

Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: a Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 | Asifa

dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 1 Deep Space Chronicle Deep Space Chronicle: A Chronology ofDeep Space and Planetary Probes, 1958–2000 |Asif A.Siddiqi National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA SP-2002-4524 A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 Asif A. Siddiqi NASA SP-2002-4524 Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 dsc_cover (Converted)-1 8/6/02 10:33 AM Page 2 Cover photo: A montage of planetary images taken by Mariner 10, the Mars Global Surveyor Orbiter, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2, all managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Included (from top to bottom) are images of Mercury, Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. The inner planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth and its Moon, and Mars) and the outer planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) are roughly to scale to each other. NASA SP-2002-4524 Deep Space Chronicle A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 ASIF A. SIDDIQI Monographs in Aerospace History Number 24 June 2002 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of External Relations NASA History Office Washington, DC 20546-0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siddiqi, Asif A., 1966 Deep space chronicle: a chronology of deep space and planetary probes, 1958-2000 / by Asif A. Siddiqi. p.cm. – (Monographs in aerospace history; no. 24) (NASA SP; 2002-4524) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Space flight—History—20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. NASA SP; 4524 TL 790.S53 2002 629.4’1’0904—dc21 2001044012 Table of Contents Foreword by Roger D. -

NASA and Planetary Exploration

**EU5 Chap 2(263-300) 2/20/03 1:16 PM Page 263 Chapter Two NASA and Planetary Exploration by Amy Paige Snyder Prelude to NASA’s Planetary Exploration Program Four and a half billion years ago, a rotating cloud of gaseous and dusty material on the fringes of the Milky Way galaxy flattened into a disk, forming a star from the inner- most matter. Collisions among dust particles orbiting the newly-formed star, which humans call the Sun, formed kilometer-sized bodies called planetesimals which in turn aggregated to form the present-day planets.1 On the third planet from the Sun, several billions of years of evolution gave rise to a species of living beings equipped with the intel- lectual capacity to speculate about the nature of the heavens above them. Long before the era of interplanetary travel using robotic spacecraft, Greeks observing the night skies with their eyes alone noticed that five objects above failed to move with the other pinpoints of light, and thus named them planets, for “wan- derers.”2 For the next six thousand years, humans living in regions of the Mediterranean and Europe strove to make sense of the physical characteristics of the enigmatic planets.3 Building on the work of the Babylonians, Chaldeans, and Hellenistic Greeks who had developed mathematical methods to predict planetary motion, Claudius Ptolemy of Alexandria put forth a theory in the second century A.D. that the planets moved in small circles, or epicycles, around a larger circle centered on Earth.4 Only partially explaining the planets’ motions, this theory dominated until Nicolaus Copernicus of present-day Poland became dissatisfied with the inadequacies of epicycle theory in the mid-sixteenth century; a more logical explanation of the observed motions, he found, was to consider the Sun the pivot of planetary orbits.5 1. -

Case Study of the Internal Growth Dynamics of NASA

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1971 Case study of the internal growth dynamics of NASA Bruce M. Whitehead The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Whitehead, Bruce M., "Case study of the internal growth dynamics of NASA" (1971). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1747. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1747 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CASE STUDY OF THE INTERNAL GROWTH DYNAMICS OF NASA By Bruce M. Whitehead B.A. University of Montana, 1970 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1971 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners Dea^ Grad^txe 7/ UMI Number: EP35189 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI OlM«rt*tk>n Publishing UMI EP35189 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Into the Unknown Together the DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight

Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page i Into the Unknown Together The DOD, NASA, and Early Spaceflight MARK ERICKSON Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 2005 Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Erickson, Mark, 1962- Into the unknown together : the DOD, NASA and early spaceflight / Mark Erick- son. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-140-6 1. Manned space flight—Government policy—United States—History. 2. National Aeronautics and Space Administration—History. 3. Astronautics, Military—Govern- ment policy—United States. 4. United States. Air Force—History. 5. United States. Dept. of Defense—History. I. Title. 629.45'009'73––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the editor and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public re- lease: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page iii To Becky, Anna, and Jessica You make it all worthwhile. THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Frontmatter 11/23/05 10:12 AM Page v Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii DEDICATION . iii ABOUT THE AUTHOR . ix 1 NECESSARY PRECONDITIONS . 1 Ambling toward Sputnik . 3 NASA’s Predecessor Organization and the DOD . 18 Notes . 24 2 EISENHOWER ACT I: REACTION TO SPUTNIK AND THE BIRTH OF NASA . 31 Eisenhower Attempts to Calm the Nation .