Pioneer Venus Multiprobe Entry Telemetry Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

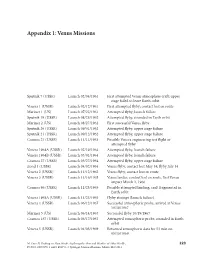

Appendix 1: Venus Missions

Appendix 1: Venus Missions Sputnik 7 (USSR) Launch 02/04/1961 First attempted Venus atmosphere craft; upper stage failed to leave Earth orbit Venera 1 (USSR) Launch 02/12/1961 First attempted flyby; contact lost en route Mariner 1 (US) Launch 07/22/1961 Attempted flyby; launch failure Sputnik 19 (USSR) Launch 08/25/1962 Attempted flyby, stranded in Earth orbit Mariner 2 (US) Launch 08/27/1962 First successful Venus flyby Sputnik 20 (USSR) Launch 09/01/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Sputnik 21 (USSR) Launch 09/12/1962 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Cosmos 21 (USSR) Launch 11/11/1963 Possible Venera engineering test flight or attempted flyby Venera 1964A (USSR) Launch 02/19/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Venera 1964B (USSR) Launch 03/01/1964 Attempted flyby, launch failure Cosmos 27 (USSR) Launch 03/27/1964 Attempted flyby, upper stage failure Zond 1 (USSR) Launch 04/02/1964 Venus flyby, contact lost May 14; flyby July 14 Venera 2 (USSR) Launch 11/12/1965 Venus flyby, contact lost en route Venera 3 (USSR) Launch 11/16/1965 Venus lander, contact lost en route, first Venus impact March 1, 1966 Cosmos 96 (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Possible attempted landing, craft fragmented in Earth orbit Venera 1965A (USSR) Launch 11/23/1965 Flyby attempt (launch failure) Venera 4 (USSR) Launch 06/12/1967 Successful atmospheric probe, arrived at Venus 10/18/1967 Mariner 5 (US) Launch 06/14/1967 Successful flyby 10/19/1967 Cosmos 167 (USSR) Launch 06/17/1967 Attempted atmospheric probe, stranded in Earth orbit Venera 5 (USSR) Launch 01/05/1969 Returned atmospheric data for 53 min on 05/16/1969 M. -

Ultraviolet Imager on Venus Orbiter Akatsuki

Yamazaki et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2018) 70:23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0772-6 FULL PAPER Open Access Ultraviolet imager on Venus orbiter Akatsuki and its initial results Atsushi Yamazaki1,2*, Manabu Yamada3, Yeon Joo Lee1,4, Shigeto Watanabe5, Takeshi Horinouchi6, Shin‑ya Murakami1, Toru Kouyama7, Kazunori Ogohara8, Takeshi Imamura9, Takao M. Sato1, Yukio Yamamoto1, Tetsuya Fukuhara10, Hiroki Ando11, Ko‑ichiro Sugiyama12, Seiko Takagi13,14, Hiroki Kashimura15, Shoko Ohtsuki16, Naru Hirata17, George L. Hashimoto18, Makoto Suzuki1, Chikako Hirose1, Munetaka Ueno19, Takehiko Satoh1,20, Takumi Abe1,20, Nobuaki Ishii1 and Masato Nakamura1 Abstract The ultraviolet imager (UVI) has been developed for the Akatsuki spacecraft (Venus Climate Orbiter mission). The UVI takes ultraviolet (UV) images of the solar radiation refected by the Venusian clouds with narrow bandpass flters centered at the 283 and 365 nm wavelengths. There are absorption bands of SO 2 and unknown absorbers in these wavelength regions. The UV images provide the spatial distribution of SO2 and the unknown absorber around cloud top altitudes. The images also allow us to understand the cloud top morphologies and haze properties. Nominal sequential images with 2-h intervals are used to understand the dynamics of the Venusian atmosphere by estimating the wind vectors at the cloud top altitude, as well as the mass transportation of UV absorbers. The UVI is equipped with of-axial catadioptric optics, two bandpass flters, a difuser installed in a flter wheel moving with a step motor, and a high sensitivity charge-coupled device with UV coating. The UVI images have spatial resolutions ranging from 200 m to 86 km at sub-spacecraft points. -

Planetary Exploration : Progress and Promise

PLANET ARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENTS: NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS: SIGNIFICANT EVENTS PLANETARY EXPLORATION PROGRESS-1978 NASA SPACE SCIENCE PROGRAM FUNDING: 5 -YEAR PLAN NASA OSS 5-YEAR PLAN: PLANETARY PROGRAM FUNDING REFERENCE COP'I PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist Lunar and Planetary Institute 3303 NASA Road One Houston, Texas 77058 Lunar and Planetary Institute Contribution No. 297 (June 1978 update> NASA PLANETARY EXPLORATION PLANS SIGNIFICANT EVENTS MISSION EVENTS PIONEER VENUS ORBITER ORBIT INSERTION, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER VENUS MULTIPROBE VENUS ENCOUNTER/ENTRY, DECEMBER 1978 PIONEER 11 SATURN ENCOUNTER, SEPTEMBER 1979 VOYAGER 1 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, MARCH 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1980 VOYAGER 2 JUPITER ENCOUNTER, JULY 1979 SATURN ENCOUNTER, AUGUST 1981 URANUS ENCOUNTER, JANUARY 1986 SOLAR MAXIMUM MISSION LAUNCH, OCTOBER 1979 VENUS ORBITAL IMAGING RADAR VENUS ENCOUNTER, SPRING 1985 SOLAR POLAR MISSION JUPITER ENCOUNTER, 1984 SOLAR POLES PASSAGE, 1986 GALILEO MISSION MARS FLYBY, APRIL 1982 JUPITER ENCOUNTER (ORBIT INSERTION/ PROBE ENTRY), 1985 COMET HALLEYlTEMPEL, . 2'J MISSION• HALLEY ENCOUNTER, NOVEMBER 1985 TEMPEL 2 ENCOUNTER, JULY 1988 or COMET ENCKE RENDEZVOUS ENCKE ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS GEOCHEMICAL ORBITER MARS ENCOUNTER, 1987 MARS SAMPLE RETURN MARS ENCOUNTER, 1989 EARTH RETURN, 1991 SATURN ORBITER DUAL PROBE SATURN ENCOUNTER, 1992 from NASA Headquarters 5-year plan May 1978 PLANETARY EXPLORATION -- PROGRESS AND PROMISE CONTENT S: Planetary exploration progress - 1977 fig. 1 The future fig. 2 Inner planets plan fig. 3 Outer planets plan fig. 4 Small bodies plan fig. 5 compiled by Dr. Leonard Srnka, Staff Scientist LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE 3303 NASA Road One Houston, TX 77058 September 1977 LUNAR SCIENCE INSTITUTE CONTRIBUTION No. -

Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite Significant Contributions to Many Mass Spectrometer Projects from Battell Enginee

GSFC Mass Spectrometer Development Team (Present and Near Past) Paul Mahaffy/699 Bob Arvey/540-Ball Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) Instrument Suite Dave McClaeb/540-SGT Florence Tan/565 Instrument scientist and Aerospace SAM engineering Electronics engineer for SAM principal Senior electronics technician SAM, LADEE NMS and investigator, 699 lab chief technician, flight hardware MAVEN NGIMS, aka “Queen assembly and testing of Everything” Mike Barciniak/699 Ball Aerospace Rob Chalmers/545 Ryan Wilkinson/540- Kiran Patel/699-Mantech Senior electronics tech, Lead SAM Thermal QINETIQ Software engineer, ESD lab monitor and subsystem engineer SAM engineering development of lab and EGSE designer technician ground support equipment QMS Dan Harpold/699 Vince Holmes/543- John Bishop/540-QINETiQ Pete Piazza/547- QMS lead and expert, Bastion Technologies Engineering technician and Oceaneering contracting officer’s Lead mechanical design expert cup loader, aka “Mr. The Mars Chamber Senior mechanical technical representative for SAM, LADEE NMS and Hands” technician MAVIN NGIMS . for contracts The Planetary Environments Laboratory team and partners have Doug Hawk/540-Swales Eric Raaen/699-SGT successfully built and flown mass spectrometer instruments for Dennis Nehl/Bastion Todd King/556 Engineer, lead SAM Software engineer, lead measuring gas composition on a variety of Earth and planetary Instrument technician, Materials engineer, hydrocarbon trap mass spectrometer missions since the 1960’s. Earth instruments include Atmospheric SAM environmental LADEE -

Venus Exploration Opportunities Within NASA's Solar System Exploration Roadmap

Venus Exploration Opportunities within NASA's Solar System Exploration Roadmap by Tibor Balint1, Thomas Thompson1, James Cutts1 and James Robinson2 1Jet Propulsion Laboratory / Caltech 2NASA HQ Presented at the Venus Entry Probe Workshop European Space Agency (ESA) European Space and Technology Centre (ESTEC) The Netherlands January 19-20, 2006 By Tibor Balint, JPL, November 8, 2005 Balint, JPL, November Tibor By 1 Acknowledgments • Solar System Exploration Road Map Team • NASA HQ – Ellen Stofan – James Robinson –Ajay Misra • Planetary Program Support Team – Steve Saunders – Adriana Ocampoa – James Cutts – Tommy Thompson • VEXAG Science Team – Tibor Balint – Sushil Atreya (U of Michigan) – Craig Peterson – Steve Mackwell (LPI) – Andrea Belz – Martha Gilmore (Wesleyan University) – Elizabeth Kolawa – Michael Pauken – Alexey Pankine (Global Aerospace Corp) – Sanjay Limaye (University of Wisconsin-Madison) • High Temperature Balloon Team – Kevin Baines (JPL) – Jeffery L. Hall – Bruce Banerdt (JPL) – Andre Yavrouian – Ellen Stofan (Proxemy Research, Inc.) – Jack Jones – Viktor Kerzhanovich Other JPL candidates – Suzanne Smrekar (JPL) • Radioisotope Power Systems Study Team – Dave Crisp (JPL) – Jacklyn Green Astrobiology – Bill Nesmith – David Grinspoon (University of Colorado) – Rao Surampudi – Adam Loverro By Tibor Balint, JPL, November 8, 2005 Balint, JPL, November Tibor By 2 Overview • Brief Summary of Past Venus In-situ Missions • Recent Solar System Exploration Strategic Plans • Potential Future Venus Exploration Missions • New Technology -

ISSUE 134, AUGUST 2013 2 Imperative: Venus Continued

Imperative: Venus — Virgil L. Sharpton, Lunar and Planetary Institute Venus and Earth began as twins. Their sizes and densities are nearly identical and they stand out as being considerably more massive than other terrestrial planetary bodies. Formed so close to Earth in the solar nebula, Venus likely has Earth-like proportions of volatiles, refractory elements, and heat-generating radionuclides. Yet the Venus that has been revealed through exploration missions to date is hellishly hot, devoid of oceans, lacking plate tectonics, and bathed in a thick, reactive atmosphere. A less Earth-like environment is hard to imagine. Venus, Earth, and Mars to scale. Which L of our planetary neighbors is most similar to Earth? Hint: It isn’t Mars. PWhy and when did Earth’s and Venus’ evolutionary paths diverge? This fundamental and unresolved question drives the need for vigorous new exploration of Venus. The answer is central to understanding Venus in the context of terrestrial planets and their evolutionary processes. In addition, however, and unlike virtually any other planetary body, Venus could hold important clues to understanding our own planet — how it has maintained a habitable environment for so long and how long it can continue to do so. Precisely because it began so like Earth, yet evolved to be so different, Venus is the planet most likely to cast new light on the conditions that determine whether or not a planet evolves habitable environments. NASA’s Kepler mission and other concurrent efforts to explore beyond our star system are likely to find Earth-sized planets around Sun-sized stars within a few years. -

Mission Overview the Pioneer Mission Set the Stage for U.S. Space

Mission Overview The Pioneer mission set the stage for U.S. space exploration. Pioneer 1 was the first manmade object to escape the Earth's gravitational field. Later Pioneer 4 was the first spacecraft to fly to the moon, Pioneer 10 was the first to Jupiter, Pioneer 11 was the first to Saturn and Pioneer 12 was the first U.S. spacecraft to orbit another planet, Venus. The following table summarizes the Pioneer spacecraft and scientific objectives of the Pioneer mission. Name Launch Mission Status (as of 1998) ----------------------------------------------------------------- Pioneer 1 1958-10-11 Moon Reached altitude of 72765 miles Pioneer 2 1958-11-08 Moon Reached altitude of 963 miles Pioneer 3 1958-12-02 Moon Reached altitude of 63580 miles Pioneer 4 1959-03-03 Moon Passed by moon into solar orbit Pioneer 5 1960-03-11 Solar Orbit Entered solar orbit Pioneer 6 1965-12-16 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 7 1966-08-17 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 8 1967-12-13 Solar Orbit Still operating Pioneer 9 1967-11-08 Solar Orbit Signal lost in 1983 Pioneer E 1969-08-07 Solar Orbit Launch failure Pioneer10 1972-03-02 Jupiter Communication terminated 1998 Pioneer11 1972-03-02 Jupiter/Saturn Communication terminated 1997 Pioneer12 1978-05-20 Venus Entered Venus atmos. 1992-10-08 The focus of this document is on Pioneer Venus (12), the last spacecraft in a mission of firsts in space exploration. Probe Separation: Pioneer Venus separated into two spacecraft on Aug 8, 1978: an Orbiter (PVO) and a Multiprobe. The latter was separated into five separate vehicles near Venus. -

Hesperos: a Geophysical Mission to Venus

Hesperos: A geophysical mission to Venus Robert-Jan Koopmansa,∗, Agata Bia lekb, Anthony Donohoec, Mar´ıa Fern´andezJim´enezd, Barbara Frasle, Antonio Gurciullof, Andreas Kleinschneiderg, AnnaLosiak h, Thurid Manneli, I~nigoMu~nozElorzaj, Daniel Nilssonk, Marta Oliveiral, Paul Magnus Sørensen-Clarkm, Ryan Timoneyn, Iris van Zelsto aFOTEC Forschungs- und Technologietransfer GmbH, Wiener Neustadt, Austria bSpace Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland cMaynooth University, Department of Experimental Physics, Maynooth, Ireland dUniversidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain eZentralanstalt f¨urMeteorologie und Geodynamik, Vienna, Austria fRoyal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden gDelft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands hInstitute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Science, Wroclaw, Poland iInstitute for Space Research, Austrian Academy of Sciences jHE Space Operations GmbH, Bremen, Germany kLule˚aUniversity of Technology, Lule˚a,Sweden lInstituto Superior T´ecnico, Lisbon, Portugal mUniversity of Oslo, Oslo, Norway nUniversity of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom oInstitute of Geophysics, ETH Z¨urich,Z¨urich,Switzerland Abstract The Hesperos mission proposed in this paper is a mission to Venus to in- vestigate the interior structure and the current level of activity. The main questions to be answered with this mission are whether Venus has an internal structure and composition similar to Earth and if Venus is still tectonically active. To do so the mission will consist of two elements: an orbiter to in- vestigate the interior and changes over longer periods of time and a balloon floating at an altitude between 40 and 60km~ to investigate the composition arXiv:1803.06652v1 [astro-ph.EP] 18 Mar 2018 of the atmosphere. The mission will start with the deployment of the balloon which will operate for about 25 days. -

Ultraviolet Imager on Venus Orbiter Akatsuki and Its Initial Results

Yamazaki et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2018) 70:23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-017-0772-6 FULL PAPER Open Access Ultraviolet imager on Venus orbiter Akatsuki and its initial results Atsushi Yamazaki1,2*, Manabu Yamada3, Yeon Joo Lee1,4, Shigeto Watanabe5, Takeshi Horinouchi6, Shin‑ya Murakami1, Toru Kouyama7, Kazunori Ogohara8, Takeshi Imamura9, Takao M. Sato1, Yukio Yamamoto1, Tetsuya Fukuhara10, Hiroki Ando11, Ko‑ichiro Sugiyama12, Seiko Takagi13,14, Hiroki Kashimura15, Shoko Ohtsuki16, Naru Hirata17, George L. Hashimoto18, Makoto Suzuki1, Chikako Hirose1, Munetaka Ueno19, Takehiko Satoh1,20, Takumi Abe1,20, Nobuaki Ishii1 and Masato Nakamura1 Abstract The ultraviolet imager (UVI) has been developed for the Akatsuki spacecraft (Venus Climate Orbiter mission). The UVI takes ultraviolet (UV) images of the solar radiation refected by the Venusian clouds with narrow bandpass flters centered at the 283 and 365 nm wavelengths. There are absorption bands of SO 2 and unknown absorbers in these wavelength regions. The UV images provide the spatial distribution of SO2 and the unknown absorber around cloud top altitudes. The images also allow us to understand the cloud top morphologies and haze properties. Nominal sequential images with 2-h intervals are used to understand the dynamics of the Venusian atmosphere by estimating the wind vectors at the cloud top altitude, as well as the mass transportation of UV absorbers. The UVI is equipped with of-axial catadioptric optics, two bandpass flters, a difuser installed in a flter wheel moving with a step motor, and a high sensitivity charge-coupled device with UV coating. The UVI images have spatial resolutions ranging from 200 m to 86 km at sub-spacecraft points. -

Extra-Terrestrial Meteors

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS apostolos christou Armagh Observatory and Planetarium College Hill, BT61 9DG Northern Ireland, UK jeremie vaubaillon IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris Paris 75014, France paul withers Astronomy Department, Boston University 725 Commonwealth Avenue Boston MA 02215, USA ricardo hueso Fisica Aplicada I Escuela de Ingenieria de Bilbao Plaza Ingeniero Torres Quevedo 1 48013 Bilbao, Spain rosemary killen NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Planetary Magnetospheres, Code 695 Greenbelt MD 20771, USA arXiv:2010.14647v1 [astro-ph.EP] 27 Oct 2020 1 1 Extra-Terrestrial Meteors 1.1 Introduction cometary orbits, all-but-invisible except where the particles are packed densely enough to be detectable, typically near The beginning of the space age 60 years ago brought about the comet itself (Sykes and Walker, 1992; Reach and Sykes, a new era of discovery for the science of astronomy. Instru- 2000; Gehrz et al., 2006). Extending meteor observations ments could now be placed above the atmosphere, allowing to other planetary bodies allows us to map out these access to new regions of the electromagnetic spectrum and streams and investigate the nature of comets whose mete- unprecedented angular and spatial resolution. But the im- oroid streams do not intersect the Earth. Observations of pact of spaceflight was nowhere as important as in planetary showers corresponding to the same stream at two or more and space science, where it now became possible – and this planets will allow to study a stream’s cross-section. In ad- is still the case, uniquely among astronomical disciplines – dition, the models used to extract meteoroid parameters to physically touch, sniff and directly sample the bodies and from the meteor data are fine-tuned, to a certain degree, for particles of the solar system. -

Space Exploration #17.Pptx

21-01-03 Rocketry Pioneers Space Exploration Part 1 • Konstantin Tsiolkovsky • Robert Goddard • Hermann Oberth • Wernher von Braun • Sergei Korolev PAA Novice Class # 16 January 8, 2021 NASA Brett Hardy First Artificial Satellite American Response Sputnik I- October 4, 1957 • Explorer I Sputnik II • Vanguard Sputnik III Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum NASA 1 21-01-03 Luna Program First Manned Launch • Luna 2 • Yuri Gagarin • Launched September 12, 1959 • April 12, 1961 • Impact September 14th • One, 108 minute orbit Russian Academy of Sciences First American in Space Sun • Alan Shepard • Pioneer 5 – 9 (1960 – 1983) • May 5, 1961 • Helios A & B (1974 – 1985) • Suborbital 15 minute flight • SOHO (1996 - Present • John Glenn • Stereo A & B (2006 -2016) • February 20, 1962 • 3 orbits, 4 hours 55 minutes ESA/NASA 2 21-01-03 Mercury Venus • Mariner 10 (1974 – 1975) • Venera 1 – 16 (1961 – 1984) • Messenger (2008 – 2015) • Mariner 2, 5, 10 (1962 – 1974) • Pioneer Venus Orbiter (1978 – 1992) • Pioneer Venus Multiprobe (1978) • Vega 1 & 2 (1985) • Magellan (1990 – 1994) NASA NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution Low Earth Orbit: Space Stations Low Earth Orbit: Satellites • Salyut 1 • Anik Communication Satellites • April 19, 1971 • Mir • Anik A1: November 9, 1972 • February 20, 1986 - 1996 • Skylab • May 14, 1973 – February 1974 • ISS • 1998 – Present • First crew: November 2, 2000 NASA Telesat Canada 3 21-01-03 Earth’s Moon • First explored extraterrestrial object • Most explored extraterrestrial