Acalypha Australis (Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take?

[email protected] • (479) 575-7646 www.nationalaglawcenter.org An Agricultural Law Research Publication Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take? by Tiffany Dowell Lashmet Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service This material is based upon work supported by the National Agricultural Library, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. An Agricultural & Food Law Consortium Project Potential Spray Drift Damage: What Steps to Take? Tiffany Dowell Lashmet Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service As many farmers know all too well, applications of various pesticides can result in drift and cause damage to neighboring property owners. In recent years, incidences of spray drift damage have been frequent and well-publicized. In the event a farmer discovers damage to his or her own crop, it is important for the injured producer to know some steps to take. Document, Document, Document First and foremost, any farmer who suspects possible injury from drift should document all potential evidence, including taking photographs or samples of damaged crops or foliage, keeping a log of spray applications made by neighboring landowners, noting any custom applicators applying pesticide in the area, documenting environmental conditions like wind speed, direction, and temperatures, and getting statements from any witnesses who might have seen recent pesticide applications. Photographs should be taken continually for several days, as the full extent of damage may not occur for several weeks after application. The more documentation a landowner has, the better his chances of recovery will be; whether it is from the offender, the offender’s insurance or potentially even the injured party’s insurance. -

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW of the LITERATURE 2.1 Taxa And

CHAPTER 2 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE 2.1 Taxa and Classification of Acalypha indica Linn., Bridelia retusa (L.) A. Juss. and Cleidion javanicum BL. 2.11 Taxa and Classification of Acalypha indica Linn. Kingdom : Plantae Division : Magnoliophyta Class : Magnoliopsida Order : Euphorbiales Family : Euphorbiaceae Subfamily : Acalyphoideae Genus : Acalypha Species : Acalypha indica Linn. (Saha and Ahmed, 2011) Plant Synonyms: Acalypha ciliata Wall., A. canescens Wall., A. spicata Forsk. (35) Common names: Brennkraut (German), alcalifa (Brazil) and Ricinela (Spanish) (36). 9 2.12 Taxa and Classification of Bridelia retusa (L.) A. Juss. Kingdom : Plantae Division : Magnoliophyta Class : Magnoliopsida Order : Malpighiales Family : Euphorbiaceae Genus : Bridelia Species : Bridelia retusa (L.) A. Juss. Plant Synonyms: Bridelia airy-shawii Li. Common names: Ekdania (37,38). 2.13 Taxa and Classification of Cleidion javanicum BL. Kingdom : Plantae Subkingdom : Tracheobionta Superdivision : Spermatophyta Division : Magnoliophyta Class : Magnoliopsida Subclass : Magnoliopsida Order : Malpighiales Family : Euphorbiaceae Genus : Cleidion Species : Cleidion javanicum BL. Plant Synonyms: Acalypha spiciflora Burm. f. , Lasiostylis salicifolia Presl. Cleidion spiciflorum (Burm.f.) Merr. Common names: Malayalam and Yellari (39). 10 2.2 Review of chemical composition and bioactivities of Acalypha indica Linn., Bridelia retusa (L.) A. Juss. and Cleidion javanicum BL. 2.2.1 Review of chemical composition and bioactivities of Acalypha indica Linn. Acalypha indica -

![Entry for ACALYPHA Acrogyna Pax [Family EUPHORBIACEAE]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8673/entry-for-acalypha-acrogyna-pax-family-euphorbiaceae-78673.webp)

Entry for ACALYPHA Acrogyna Pax [Family EUPHORBIACEAE]

Entry for ACALYPHA acrogyna Pax [family EUPHORBIACEAE] http://plants.jstor.org/flora/flota011327 http://www.jstor.org Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the contributing partner regarding any further use of this work. Partner contact information may be obtained at http://plants.jstor.org/page/about/plants/PlantsProject.jsp. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Page 1 of 2 Entry for ACALYPHA acrogyna Pax [family EUPHORBIACEAE] Herbarium Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K) Collection Flora of Tropical Africa Resource Type Reference Sources Entry from Flora of Tropical Africa, Vol 6 Part 1, page 441 (1913) Author: (By J. G. Baker, with additions by C. H. Wright.) Names ACALYPHA acrogyna Pax [family EUPHORBIACEAE], in Engl. Jahrb. -

Species List (PDF)

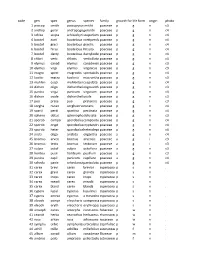

code gen spec genus species family growth formlife form origin photo 1 pascop smith pascopyrumsmithii poaceae p g n c3 2 androp gerar andropogongerardii poaceae p g n c4 3 schiza scopa schizachyriumscoparium poaceae p g n c4 4 boutel curti bouteloua curtipendulapoaceae p g n c4 5 boutel graci bouteloua gracilis poaceae p g n c4 6 boutel hirsu bouteloua hirsuta poaceae p g n c4 7 boutel dacty bouteloua dactyloidespoaceae p g n c4 8 chlori verti chloris verticillata poaceae p g n c4 9 elymus canad elymus canadensispoaceae p g n c3 10 elymus virgi elymus virginicus poaceae p g n c3 11 eragro spect eragrostis spectabilis poaceae p g n c4 12 koeler macra koeleria macrantha poaceae p g n c3 13 muhlen cuspi muhlenbergiacuspidata poaceae p g n c4 14 dichan oligo dichantheliumoligosanthespoaceae p g n c3 15 panicu virga panicum virgatum poaceae p g n c4 16 dichan ovale dichantheliumovale poaceae p g n c3 17 poa prate poa pratensis poaceae p g i c3 18 sorgha nutan sorghastrumnutans poaceae p g n c4 19 sparti pecti spartina pectinata poaceae p g n c4 20 spheno obtus sphenopholisobtusata poaceae p g n c3 21 sporob compo sporoboluscomposituspoaceae p g n c4 22 sporob crypt sporoboluscryptandruspoaceae p g n c4 23 sporob heter sporobolusheterolepispoaceae p g n c4 24 aristi oliga aristida oligantha poaceae a g n c4 25 bromus arven bromus arvensis poaceae a g i c3 26 bromus tecto bromus tectorum poaceae a g i c3 27 vulpia octof vulpia octoflora poaceae a g n c3 28 hordeu pusil hordeum pusillum poaceae a g n c3 29 panicu capil panicum capillare poaceae a g n c4 30 schedo panic schedonnarduspaniculatuspoaceae p g n c4 31 carex brevi carex brevior cyperaceaep s n . -

Leaf Epidermal Studies of Three Species of Acalypha Linn

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2012, 3 (5):3185-3199 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Leaf epidermal studies of three species of Acalypha Linn. (Euphorbiaceae) 1* Essiett Uduak Aniesua and 1Etukudo Inyene Silas Department of Botany and Ecological Studies, University of Uyo, Uyo _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Leaf epidermal studies of three species of Acalypha are described. The mature stomata were laterocytic, staurocytic, anisocytic, paracytic and diacytic. The abnormalities noticed include unopen stomatal pore, two stomata sharing one subsidiary cell, one guard cell, parallel contiguous and aborted guard cell. A. godseffiana can be distinguished by parallel contiguous on both surfaces. Curved uniseriate non-glandular trichomes were restricted to A. wilkesiana. Two stomata sharing one subsidiary cell occurred only on the lower surface of A. hispida. The shapes of epidermal anticlinal cell walls, guard cell areas, stomata index and trichomes varied. The differences are of taxonomic importance and can be used to identify and delimit each species by supporting other systematic lines of evidence. Keywords: Acalypha species, Epidermal, Stomata, Nigeria, Euphorbiaceae. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Euphorbiaceae, the spurge family of the flowering plants with 500 genera and around 7,500 species. Most are herbs, -

Revision of the Genus Cleidion (Euphorbiaceae) in Malesia

BLUMEA 50: 197–219 Published on 22 April 2005 http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/000651905X623373 REVISION OF THE GENUS CLEIDION (EUPHORBIACEAE) IN MALESIA KRISTO K.M. KULJU & PETER C. VAN WELZEN Nationaal Herbarium Nederland, Universiteit Leiden branch, P.O. Box 9514, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] SUMMARY A revision of the Malesian species in the genus Cleidion is presented. Cleidion javanicum is shown to be the correct name for the widespread type species (instead of the name C. spiciflorum). A new species, C. luziae, resembling C. javanicum, is described from the Moluccas, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. In addition, C. salomonis is synonymised with C. papuanum and C. lanceolatum is treated as a variety of C. ramosii. In total 7 Malesian Cleidion species are recognized. Cleidion megistophyllum from the Philippines cannot reliably be confirmed to belong to the genus due to lack of information and specimens and is treated as a doubtful species. Key words: Cleidion, Acalypheae, Cleidiinae, revision, taxonomy, Malesia. INTRODUCTION Cleidion is a pantropical genus belonging to the large angiosperm family Euphorbiaceae s.s. It was described by Blume (1825), who included a single species C. javanicum1. The first revision was made by Müller Argoviensis (1865, 1866). His work was fol- lowed by the comprehensive treatment of Pax & Hoffmann (1914), which included 17 species. Pax & Hoffmann excluded the section Discocleidion Müll.Arg. which differs from Cleidion by the presence of a staminate and pistillate disc (in Cleidion a disc is absent), stipellate and palmatinerved leaves (in Cleidion the leaves are non-stipellate and pinnatinerved), and differences in anther type. -

Beneficial Native Plants

Partridge Pea Goldenrods Beneficial Chamaechrista fasiculata Solidage spp. An excellent soil builder, that MOTH HOST PLANT establishes rapidly and pro- Goldenrods are Native Plants vides erosion control and attractive sources of nitrogen fixation for slower nectar for bees, flies, ...Or is that weed something I should pull out? growing perennial forbs. The wasps, moths and While many gardeners know there are inva- showy flowers are pollinated butterflies. sive, exotic (non-native) weeds they should be primarily by bumble bees Goldenrods have a while short-tongued bees, number of species, diligent about removing from the landscape, predatory wasps, hover flies and tachinid flies suck some of which not all “weeds” are a problem. Here is a list of Happy Wildlife nectar from glands on the leaf petioles. are a reasonable garden size and not aggressive some “good weeds” to leave in the wilder Gardening! Blooms July to September. in their spreading. Goldenrod does NOT have spaces of your gardens – and save time weed- wind- born pollen. Giant ragweed is what triggers ing! Common Black sneezing at the time they bloom. Blooms Snakeroot September to October. …Why? As we have discov- Sanicula odorata Need more information? Asters ered with milkweed, these Attracts small bees. Symphyotricum native plants can be critical Seeds are spread by Here are some places to look: spp. for our wildlife. Native bees mammals. Blooms May http://dda.delaware.gov/plantind/forms/publications BUTTERFLY HOST and butterflies are in decline to July. /Delaware%20Native%20Plants%20for%20Native%2 PLANT as we lose native plants every 0Bees.pdf Many different day to development, mani- Beggar Tick or Devil’s http://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/woodland/plants species, that can cured gardens and roadsides, beggar Tick establish rapidly Hairy Heath Aster as well as competition from http://www.wildflower.org/plants Bidens frondosa on disturbed sites Symphyotricum pilosum invasive plants. -

Hophornbeam Copperleaf

Extension W120 Hophornbeam Copperleaf Larry Steckel, Assistant Professor, Plant Sciences Hophornbeam Copperleaf Acalypha ostryifolia Riddell. Also known as pineland three-seeded mercury. Classifi cation and Description Hophornbeam (H) copperleaf is a member of the Euphorbiaceae or spurge family. H copperleaf has a very characteristic heart-shaped serrated leaf. The other cop- perleaf species in Tennessee, Virginia copperleaf, does not have serrations on the leaves. H copperleaf can grow to heights of 1 to 4 feet. Its leaves are alternate; blades simple. Tennessee producers sometimes misidentify it as a pig- weed. The reason for this mistake is that H copperleaf has a similar emergence pattern as pigweed. In addition, it is very tolerant to ALS-inhibiting herbicides such as Envoke®, Classic® and Steadfast®, which is also consistent with the pigweed species Palmer amaranth. H copperleaf typically emerges from June to September and reproduces by seeds Late-emerging copperleaf in cotton numbering as high as 12,500 seeds per plant, according to a Kansas study. The male owers of H copperleaf are found on auxillary spikes, while the female owers are on a long terminal spike. Historical H copperleaf is native to Tennessee and can be found throughout the state in agronomic crops, pastures, or- chards, roadsides and waste areas. H copperleaf was not a major problem in Tennessee agronomic crops until early this decade. The advent of no-till row crop production along with Roundup Ready® crops has become a good niche environment for this weed. The reduction in the use of cultivation and applications of soil-applied residual her- bicides has helped this weed become more established in Tennessee. -

Flora and Vegetation Characteristics of the Natural Habitat of the Endangered Plant Pterygopleurum Neurophyllum

diversity Article Flora and Vegetation Characteristics of the Natural Habitat of the Endangered Plant Pterygopleurum neurophyllum Hwan Joon Park 1,2,*, Seongjun Kim 1,* , Chang Woo Lee 1, Nam Young Kim 1, Jung Eun Hwang 1, Jiae An 1, Hyeong Bin Park 1, Pyoung Beom Kim 3 and Byoung-Doo Lee 1 1 Division of Restoration Research, Research Center for Endangered Species, National Institute of Ecology, Yeongyang 36531, Korea; [email protected] (C.W.L.); [email protected] (N.Y.K.); [email protected] (J.E.H.); [email protected] (J.A.); [email protected] (H.B.P.); [email protected] (B.-D.L.) 2 Department of Ecology Landscape Architecture-Design, Jeonbuk University, Iksan 54596, Korea 3 Wetland Center, National Institute of Ecology, Changnyeong 50303, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.J.P.); [email protected] (S.K.) Abstract: This study analyzed the flora, life form, and vegetation of the Nakdong River wetland. Vegetation analysis was performed on 37 plots using the phytosociological method of the Zürich- Montpellier School. PCA analysis was conducted by using the vegetation data (ground cover of class; 1~9) of 37 plots surveyed by phytosociological method. PCA (Principal Component Analysis) was used to statistically analyze the objectivity of the community classification and the character species. The traditional classification and mathematical statistic methods were used. A total of 82 taxa belonging to 28 families, 65 genera, 72 species, 2 subspecies, and 8 varieties were present in the vegetation of the survey area. The life form was analyzed to be the Th-R5-D4-e type. -

U.S. EPA, Pesticide Product Label, COBRA HERBICIDE, 06/27/2007

~,..-. , o~-2r--2()();Z UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 JUN 2 7 2007 OFFICE OF PREVENTION, PESTICIDES AND TOXIC SUBSTANCES James Pensyl Valent U.S.A. Corporation 1600 Riviera Avenue P.O. Box 8025 Walnut Creek, CA 94596 Dear Mr. Pensyl: I Subject: Add Use on Fruiting Vegetables and Okra. Cobra Herbicide EPA Registration No. 59639-34 Your Submissions Dated May 7,2007 The amendment referred to above, submitted in connection with registration under section 3(c)(7)(8) of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), is acceptable provided that you: 1. Submit/cite all data required for registration/reregistration of your product under FIFRA section 3(c)(5) or 4(a) when the Agency requires all registrants of similar products to submit such data .. 2. Submit one (1) copy of your final printed la~elingbefore you release the product for shipment. If these conditions are not complied with, the registration will be subject to cancellation in accordance with FIFRA section 6(e). Your release for shipment of the product bearing the amended labeling constitutes acceptance of these oo~~~ . A stamped copy of the label is enclosed for your records. I,f you have any questions concerning this letter please .contact ML James Stone at 703-305-7391. Sincerely yours, ~. \c . .{.,. Joanne I. Miller Product Manager (23) Herbicide Branch Registration Division (7505P) Enclosure ACCEPTED . with COMMENTS (' c. f. 1'- ') r~ ~~ (. 'J .' (. .~. ,. In EPA L.e. tter Dated: " f n;','.J:"'!' " ,. ,. J u~ 2. 7 2Of§l ,. " " ,. r:, (.0 " " , Uader the Federal Ill!l8etleide. -::'. t, tJ " (' HERBICIDE '-' fuqicide dd Rodentieide Act. -

Complete Iowa Plant Species List

!PLANTCO FLORISTIC QUALITY ASSESSMENT TECHNIQUE: IOWA DATABASE This list has been modified from it's origional version which can be found on the following website: http://www.public.iastate.edu/~herbarium/Cofcons.xls IA CofC SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME PHYSIOGNOMY W Wet 9 Abies balsamea Balsam fir TREE FACW * ABUTILON THEOPHRASTI Buttonweed A-FORB 4 FACU- 4 Acalypha gracilens Slender three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 3 Acalypha ostryifolia Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 5 UPL 6 Acalypha rhomboidea Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU 0 Acalypha virginica Three-seeded mercury A-FORB 3 FACU * ACER GINNALA Amur maple TREE 5 UPL 0 Acer negundo Box elder TREE -2 FACW- 5 Acer nigrum Black maple TREE 5 UPL * Acer rubrum Red maple TREE 0 FAC 1 Acer saccharinum Silver maple TREE -3 FACW 5 Acer saccharum Sugar maple TREE 3 FACU 10 Acer spicatum Mountain maple TREE FACU* 0 Achillea millefolium lanulosa Western yarrow P-FORB 3 FACU 10 Aconitum noveboracense Northern wild monkshood P-FORB 8 Acorus calamus Sweetflag P-FORB -5 OBL 7 Actaea pachypoda White baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Actaea rubra Red baneberry P-FORB 5 UPL 7 Adiantum pedatum Northern maidenhair fern FERN 1 FAC- * ADLUMIA FUNGOSA Allegheny vine B-FORB 5 UPL 10 Adoxa moschatellina Moschatel P-FORB 0 FAC * AEGILOPS CYLINDRICA Goat grass A-GRASS 5 UPL 4 Aesculus glabra Ohio buckeye TREE -1 FAC+ * AESCULUS HIPPOCASTANUM Horse chestnut TREE 5 UPL 10 Agalinis aspera Rough false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 10 Agalinis gattingeri Round-stemmed false foxglove A-FORB 5 UPL 8 Agalinis paupercula False foxglove -

Weed Management in Texas Corn

SCS-2017-22 Weed Management in Texas Corn Joshua McGinty, Ph.D. – Extension Agronomist – Corpus Christi, TX Scott Nolte, Ph.D. – Extension Weed Specialist – College Station, TX Ronnie Schnell, Ph.D. – Extension Cropping Systems Specialist – College Station, TX Department of Soil and Crop Sciences Contents GENERAL PRACTICES ..................................................................................................................................... 3 PREVENTATIVE WEED CONTROL ................................................................................................................... 3 CULTURAL PRACTICES ................................................................................................................................... 3 CHEMICAL CONTROL ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 1. Mechanism of action of herbicides labelled for corn ..................................................................... 6 PREPLANT BURNDOWN ................................................................................................................................ 7 WEED MANAGEMENT AT PLANTING ............................................................................................................ 7 POSTEMERGENCE WEED CONTROL .............................................................................................................. 7 POST-HARVEST WEED MANAGEMENT ........................................................................................................