Corruption and Governance in the DRC During the Transition Period (2003-2006)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Republic of Congo: Road to Political Transition

1 Democratic Republic of Congo: Road to Political Transition Dieudonné Tshiyoyo* Programme Officer Electoral and Political Processes (EPP) EISA Demographics With a total land area of 2 344 885 square kilometres that straddles the equator, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the third largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria. It is situated right at the heart of the African continent. It shares borders by nine countries, namely Angola, Burundi, Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville, Rwanda, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. Its population is estimated at 60 millions inhabitants and is made up of as many as 250 ethno-linguistic groups. The whole country is drained by the Congo River and its many tributaries. The second longest river in Africa and fifth longest in the world, the Congo River is second in the world after the Amazon with regard to hydroelectric potential. Brief Historical Background Established as a Belgian colony in 1908, the DRC was initially known as the ‘Congo Free State’ when it was formally attributed to King Leopold II at the Berlin Conference of 1885. In fact, in 1879 King Leopold II of Belgium commissioned Henry Morton Stanley to establish his authority over the Congo basin in order to control strategic trade routes to the West and Central Africa along the Congo River. Stanley did so by getting over 400 local chiefs to sign “treaties” transferring land ownership to the Association Internationale du Congo (AIC), a trust company belonging to Leopold II. On 30 April 1885 the King signed a decree creating the ‘Congo Free State’, thus establishing firm control over the enormous territory. -

The Politics of Democratic Transition in Congo (Zaire): Implications of the Kabila "Revolution"

The Politics of Democratic Transition in Congo (Zaire): Implications of the Kabila "Revolution" by Osita G. Afoaku INTRODUCTION The impetus for recent public agitation for political reform in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DROC) came from three related sources: Congo's decline in strategic and economic importance at the end of the Cold War; withdrawal of Western support for the Mobutu regime and other African dictatorships; and an intolerable level of economic hardship which added fuel to domestic demand for democracy and accountability in the public sphere.1 Although the late President Mobutu Sese Seko lifted the ban on partisan politics on 24 April 1990, his government embarked on a campaign of destabilization against the transition program. The government's strategy was centered on centralized control of public institutions which assured Mobutu the resources to co-opt, intimidate, torture and silence opposition leaders and popular constituencies. In addition, Mobutu and his acolytes resuscitated the defunct Popular Movement for the Revolution (Mouvement Populaire de la Revolution, MPR) -- the party's name was changed to Popular Movement for Renewal (Mouvement Populaire pour le renouveau, MPR) as well as sponsored the formation of shadow opposition groups. Finally, the government attempted to undermine the democratization program by instigating ethno-political conflicts among the opposition groups.2 Unfortunately, Laurent Kabila's Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (Alliance des Forces Democratiques pour la Liberation du Congo-Zaire, AFDL) brought only temporary relief to the Congolese masses when it ousted Mobutu in May 1997. Congo is among four cases identified as dissolving nation-states in a recent study of democratization in Africa. -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

Two Years Without Transition

July 1992 Vol. 4, No. 9 ZAIRE TWO YEARS WITHOUT TRANSITION "[The National Conference must produce] not only a new structure, but, especially, new leaders." Bishop Laurent Mosengwo, President of the National Sovereign Conference. "There will be no blockage or attempt to suspend [the National Conference], but a little reminder from time to time so that everyone respects the rules of the game . Overruling the chief serves no purpose. Getting on with him is called consensus." President Mobutu Sese Seko, June 20, 1992. Introduction................................................................................... .....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................2222 III The Enforced Political ImpasseImpasse.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................5............555 AAA Part One: The President's Unwilling Gift of DemocraDemocracy,cy, April 1990 to January 19921992..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................5555 -

The Political Role of the Ethnic Factor Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Political Role of the Ethnic Factor around Elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy Abstract This paper analyses the role of the ethnic factor in political choices in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and its impact on democratisa- tion and the implementation of the practice of good governance. This is done by focusing especially on the presidential and legislative elections of 1960 and 2006. The Congolese electorate is known for its ambiguous and paradoxical behaviour. At all times, ethnicity seems to play a determining role in the * Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy is a research fellow at the Centre for Management of Peace, Defence and Security at the University of Kinshasa, where he is a Ph.D. candidate in Conflict Resolution. The key areas of his research are good governance, human security and conflict prevention and resolution in the SADC and Great Lakes regions. He has written a number of articles and publications, including La transition démocratique au Zaïre (1995), L’insécurité à Kinshasa (2004), a joint work, The Many Faces of Human Security (2005), Parties and Political Transition in the Democratic Republic of Congo (2006), originally in French. He has been a researcher-consultant at the United Nations Information Centre in Kinshasa, the Centre for Defence Studies at the University of Zimbabwe, the Institute of Security Studies, Pretoria, the Electoral Institute of Southern Africa, the Southern African Institute of International Affairs and the Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. The article was translated from French by Dr Marcellin Vidjennagni Zounmenou. 219 Hubert Kabungulu Ngoy-Kangoy choice of leaders and so the politicians, entrusted with leadership, keep on exploiting the same ethnicity for money. -

African Diaspora Postcolonial Stakes of Congolese (DRC)

African Diaspora African Diaspora 6 (2013) 72-96 brill.com/afdi Postcolonial Stakes of Congolese (DRC) Political Space: 50 Years after Independence1 Sarah Demarta and Leïla Bodeuxb a) F.R.S.-FNRS research fellow, Center for Ethnic and Migration Studies (CEDEM) University of Liège, Belgium [email protected] b) MSc in African Studies, University of Oxford, 2010-2011, UK [email protected] Abstract This joint contribution interrogates the postcolonial relations that are at play in the Congolese political sphere in Belgium, the former colonial metropolis. Two lines of argument are developed. First, the politicisation of the postcolonial relations, which pre-dates the Congolese immigration to Belgium, is viewed from a historical perspective. Second, the highly competitive political plu- ralism, as observed since the early 2000s, is examined. After having restored historically the con- stitution and the reconstruction of this political sphere, wherein new technologies deepen the transnational movements, the authors will examine the tensions that arise from the unifying dynamics of the politically engaged Diaspora, on the one hand, and its intrinsic logics of division and fragmentation, on the other. The postcolonial issues that are at stake are to be seen on differ- ent levels: transnational, local, within the Diaspora, and between the Congolese minority and the Belgian majority. Their interconnectedness further reveals the postcolonial character of this political sphere. Keywords Congolese Diaspora, political involvement, Belgium, postcolonial relations Résumé Dans le cadre de cette contribution à deux voix, nous interrogeons les enjeux postcoloniaux du champ politique congolais en Belgique, l’ancienne métropole. Deux grands axes sont développés. Premièrement, la mise en perspective historique de cette politisation, avant même l’existence d’une immigration congolaise en Belgique. -

Kabila Returns, in a Cloud of Uncertainty

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 1, Issue 3 | 1997 Kabila Returns, In a Cloud of Uncertainty THOMAS TURNER INTRODUCTION Since the 1960's, Laurent Kabila had led a group of insurgents against the dictatorial Mobutu Sese Seko government in Kinshasa, operating along Zaire's eastern border 1. Kabila's group was one of the many rebel movements in the East that had arisen with the aim of furthering the political program of Congo's first prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, the popular and charismatic leader who was assassinated in 1961. The major Lumumbist insurgencies had been subdued by Mobutu using foreign mercenaries between 1965 and 1967. The small surviving groups such as that of Kabila posed no threat to the Mobutu regime. The 1994 Rwandan genocide changed all that. Approximately one million Rwanda Hutu refugees fled to eastern Zaire, which was already near the boiling point due to conflicts over land use and political representation. In an effort to break out of its diplomatic isolation, the Mobutu government provided backing to the Hutu, including army and militia elements, thereby earning the enmity of the Tutsi-dominated government in Rwanda. Tutsi of South Kivu, the so-called Banyamulenge, staged an uprising in the summer of 1996, with the support of the Rwanda government. By the second half of that year, the alliance of Banyamulenge, Tutsi of North Kivu, and Lumumbists and others, headed by Kabila, had taken over substantial parts of eastern Zaire, with the corrupt and demoralized Mobutu army disappearing in the face of their advance. After a short seven month campaign, Kabila and the new armed coalition entered Kinshasa as Mobutu fled into exile. -

La Liste De Tous Les Livres 2019

1 REPERTOIRE DE LA BIBLIOTHEQUE DU CADICEC CADICEC : LE SENS D’UN ITINERAIRE Le CADICEC a changé cinq fois de dénomination Abréviations Dénominations C.A.D.I.C.E.C Association des Cadres et Dirigeants Catholiques des Entreprises du Congo (1956 à 1960) C.A.D.I.C.E.C Association des Cadres et Dirigeants des Entreprises du Congo (1960 à 1971) C.A.D.I.C.E.C Centre Chrétien d’Action pour Dirigeants et Cadres des Entreprises du Zaïre (1971 à 1981) C.A.D.I.C.E.C Centre Chrétien d’Action pour Dirigeants et Cadres d’Entreprises installées au Zaïre (1981 à 2004) C.A.D.I.C.E.C Centre Chrétien d’Action pour Dirigeants et Cadres d’Entreprises installés en République Démocratique du Congo (2004 à nos jours) 2 Notre bibliothèque met à la disposition de ses lecteurs quelques livres, périodiques et journaux. Ils traitent les domaines suivants : OUVRAGES CODES PAGES DROIT, FISCALITE & SYNDICATS Dr. De 03 à 13 MEDECINE, SCIENCE & SANTE San. De 14 à 16 ECONOMIE & INDUSTRIE Eco. De 16 à 26 GESTION DES ENTREPRISES & DEVELOPPEMENT Ges. De 27 à 34 EDUCATION, PSYCHOLOGIE & ENSEIGNEMENT Educ. De 35 à 41 SOCIOLOGIE, POLULATION, DEMOGRAPHIE & URBANISME SOC. De 42 à 45 ROMANS & HISTOIRES DES ETATS Ro De 45 à 50 RELIGION Rel De 50 à 53 PUBLICATIONS CADICEC CDC De 54 à 134 INFORMATIQUE Info De 03 à 13 LEGISLATIONS SOCIALES (REVUES) Lég De 14 à 16 SOCIALE (LIVRES) L.S TECHNIQUE TECH. AGRICULTURE AGRI. LES BANQUES ECOBA DIVERS 3 R O I T D Codes Auteurs Editions Années Nbres Titre de livres d’édition pages Dr.1 L’inspection du travail, sa mission, ses méthodes B.I.T B.I.T. -

Democratic Republic of Congo Public Disclosure Authorized Systematic Country Diagnostic

Report No. 112733-ZR Democratic Republic of Congo Public Disclosure Authorized Systematic Country Diagnostic Policy Priorities for Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity in a Post-Conflict Country and Fragile State March 2018 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized IDA (International IFC (International MIGA (Multilateral Development Association) Finance Corporation) Investment Guaranty Agency) Vice President: Makhtar Diop Snezana Stoiljkovic Keiko Honda Director: Jean-Christophe Carret Cheikh Oumar Seydi Merli Baroudi Task Team Leaders: Emmanuel Pinto Moreira (TTL) Adamou Labara (TTL) Petal Jean Hackett Chadi Bou Habib (Co-TTL) Babacar Sedikh Faye (Co-TTL) Franck M. Adoho (Co-TTL) This report was prepared by a World Bank Group team led by Emmanuel Pinto Moreira (Lead Economist and Program leader EFI (Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions), and TTL (Task Team Leader), including Adamou Labara (Country Manager and TTL), Babacar Sedikh Faye (Resident Representative and Co-TTL), Franck M. Adoho (Senior Economist and Co-TTL), Chadi Bou-Habib (Lead Economist and Program leader EFI, and Co-TTL), Laurent Debroux (Program Leader), Luc Laviolette (Program Leader), Andreas Schiessler (Lead Transport Specialist), Alexandre Dossou (Senior Transport Specialist), Jerome Bezzina (Senior Regulatory Economist), Malcolm Cosgroves-Davies (Lead Energy Specialist), Pedro Sanchez (Lead Energy Specialist), Manuel Luengo (Senior Energy Specialist), Anas Benbarka (Senior -

La Crise D'hommes Au Congo: Les Larmes De La Honte

Benjamin Becaud Mambuana “ La crise d’hommes au Congo: les larmes de la honte” De la déchéance à la fin programmée du fameux « Brésil africain » mort né -2008- Résumé Pourquoi malgré ses importants atouts : ses ressources les plus innombrables et exceptionnelles ce pays, autrefois nommé le « Brésil africain » continue sa plongée apnée ? Des facteurs tels la colonisation, l’impérialisme, l’ingérence extérieure,…, ont été généralement évoqués pour expliquer les causes de la déliquescence de ce « pays continent » très largement gâté par la nature. Une part relativement faible des analyses accordait l’attention à la défaillance humaine pour expliquer les vraies origines du mal qui continue à compromettre le bien-être des populations congolaises. A l’évidence, autant d’hommes qui se succèdent à la tête du Congo, autant des systèmes politiques, autant des médiocrités qui gangrènent le quotidien congolais largement marqué par la racaille. La victimisation du peuple congolais demeure une réalité frappante dont la « têtutesse » de faits semble ne pas être défiée même par le point de vue de l’observateur le plus optimiste. Le Congo s’affiche à la porte des sorties de classements conventionnellement admis, n’eût été les artifices par lesquels les meilleurs experts surdoués des institutions internationales se tirent d’affaire pour justifier des potentiels signes de vie : brandissant, notamment, des chiffres dignes des coups de baguettes magiques. Cet ouvrage tente d’examiner, tout particulièrement, l’homme congolais, et sa façon de faire. Un processus de lavage de cerveaux et de dépigmentation culturelle ont été, très tôt à l’œuvre pour transmuter ce peuple dynamique d’avant l’indépendance en vulgaire danseur avili et humilié. -

Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists

African Journalism Studies ISSN: 2374-3670 (Print) 2374-3689 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/recq21 Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists Marie Fierens To cite this article: Marie Fierens (2016) Reporting on the Independence of the Belgian Congo: Mwissa Camus, the Dean of Congolese Journalists, African Journalism Studies, 37:1, 81-99, DOI: 10.1080/23743670.2015.1084584 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23743670.2015.1084584 Published online: 09 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=recq21 Download by: [Archives & Bibliothèques de l'ULB] Date: 10 March 2016, At: 00:16 REPORTING ON THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE BELGIAN CONGO: MWISSA CAMUS, THE DEAN OF CONGOLESE JOURNALISTS Marie Fierens Centre de recherche en sciences de l'information et de la communication (ReSIC) Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB) [email protected] ABSTRACT Many individuals were involved in the Belgian Congo’s attainment of independence. Born in 1931, Mwissa Camus, the dean of Congolese journalists, is one of them. Even though he was opposed to this idea and struggled to maintain his status as member of a certain ‘elite’, his career sheds light on the advancement of his country towards independence in June 1960. By following his professional career in the years preceding independence, we can see how his development illuminates the emergence of journalism in the Congo, the social position of Congolese journalists, and the ambivalence of their position towards the emancipation process. -

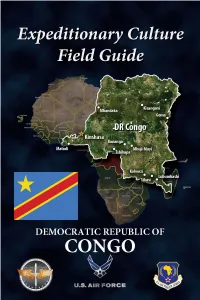

ECFG-DRC-2020R.Pdf

ECFG About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally t complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The he fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. Democratic Republicof The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), focusing on unique cultural features of the DRC’s society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of IRIN © Siegfried Modola). the For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact Congo AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society.