St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop 1. Soldiers on Every Street Corner: the War Is Announced in York

Stop 1. Soldiers on every street corner: the war is announced in York Stand in front of the Yorkshire Museum, on the steps looking out into the Gardens. During the First World War, newspapers were the main source of information for the public, explaining what was happening at home and abroad as well as forming the basis for pro-war propaganda. In York, the building that currently operates as the City Screen Picturehouse, later on you will see it between stops 4 and 5, was once the headquarters of the Yorkshire Herald Newspaper. In 1914 there were around 100,000 people living in York, half of the city’s current population, and York considered itself the capital of Yorkshire and the whole of the North of England. The Local newspapers did not wholly prepare the city’s inhabitants for Britain entering the war, as the Yorkshire Evening Press stated soon after war had been announced that ‘the normal man cared more about the activities of the household cat than about events abroad’. At the beginning of the 20th century the major European countries were incredibly powerful and had amassed great wealth, but competition for colonies and trade had created a European continent rife with tensions between the great powers. June 28th 1914 saw the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire Arch-Duke Ferdinand and his wife Sophia while on a diplomatic trip to Sarajevo by a Yugoslav Nationalist who was fighting for his country’s independence. This triggered the chain reaction which culminated in war between the European powers. -

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

45 Hampden Street, Bishophill, York, YO1 6EA

45 Hampden Street, Bishophill, York, YO1 6EA Guide Price: £230,000 A beautiful 2 bedroom town house which has been the subject of updating works over recent years situated in the highly regarded Bishophill area. DESCRIPTION This tastefully presented two bedroom town house provides accommodation which would suite a variety of purchasers from investors wanting a property for holiday lets to owner occupiers alike. Located on the sought after Hampden Street, the home offers buyers the fantastic opportunity to live within the city walls and have access to the wide and varied amenities within York city centre and also close by on Micklegate. Having being recently updated, the accommodation briefly comprises: to the ground floor; entrance hall with stairs off, sitting room with understairs office area, refitted kitchen with integrated appliances and space for a dining table, inner hall with door leading to courtyard, bathroom with white suite. To the first floor; the stairs lead to the landing area and two bedrooms. OUTSIDE To the rear is the courtyard garden which is attractively presented offering the opportunity for alfresco dining, a rarity within the city centre. LOCAL AREA The Bishophill area of York lies within the City Walls and is a few minutes walk to both the City Centre and the railway station. It is also positioned on the west side of the centre allowing easy access out to the A64, Leeds and beyond. The amenities of Bishopthorpe Road and nearby river also add to the appeal of Yorks many bar, café and retail facilities on the doorstep. 3 High Petergate York North Yorkshire YO1 7EN T: 01904 653564 F: 01904 640067 E: [email protected] . -

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday Evening 26Th August and All Day Bank Holiday Monday 27Th August 2018 Diversions to Bus Services

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday evening 26th August and all day Bank Holiday Monday 27th August 2018 Diversions to bus services Bank Holiday Monday 27th August is the third annual Micklegate Run soap box event, in the heart of York city centre. Micklegate, Bridge Street, Ouse Bridge and Low Ousegate will all be closed for the event, with no access through these roads or Rougier Street or Skeldergate. Our buses will divert: -on the evening of Sunday 26th August during set up for the event. -all day on Bank Holiday Monday 27th August while the event takes place. Diversions will be as follows. Delays are likely on all services (including those running normal route) due to increased traffic around the closed roads. Roads will close at 18:10 on Sunday 26th, any bus which will not make it through the closure in time will divert, this includes buses which will need to start the diversion prior to 18:10. Route 1 Wigginton – Chapelfields – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 2 Rawcliffe Bar Park & Ride – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 3 Askham Bar Park & Ride – Sunday 26th August: will follow its normal route up to and including the 18:05 departure from Tower Street back to Askham Bar Park & Ride. The additional Summer late night Shakespeare Theatre buses will then divert as follows: From Askham Bar Park & Ride, normal route to Blossom Street, then right onto Nunnery Lane (not serving the Rail Station into town), left Bishopgate Street, over Skeldergate Bridge to Tower Street as normal. -

Tadcaster & Healaugh Priory

TADCASTER AND HEALAUGH PRIORY A 5.5 mile moderate walk mainly easy-going on level farm tracks. There are 3 stiles and there is one short hill towards the beginning of the walk. Start point: Tadcaster Bus Station, behind Britannia Inn, Commercial Street, Tadcaster. LS24 8AA Tadcaster is the last town on the River Wharfe before it joins the River Ouse about 10 miles (16 km) downstream and is twinned with Saint Chély d'Apcher in France . The town was founded by the Romans , who named it Calcaria from the Latin word for lime, reflecting the importance of the area's limestone geology as a natural resource for quarrying , an industry which continues today and has contributed to many notable buildings including York Minster . Calcaria was an important staging post on the road to Eboracum (York ), which grew up at the river crossing. The suffix of the Anglo-Saxon name Tadcaster is derived from the borrowed Latin word castra meaning 'fort', although the Saxons used it for any walled Roman settlement. Tadcaster is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as the place where King Harold assembled his army prior to entry into York and subsequently on to the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066. The original river crossing was probably a simple ford near the present site of St Mary's Church, soon followed by a wooden bridge. Around 1240, the first stone bridge was constructed close by, possibly from stone once again reclaimed from the castle. In 1642 the Battle of Tadcaster , an incident during the English Civil War , took place on and around Tadcaster Bridge between Sir Thomas Fairfax's Parliamentarian forces and the Earl of Newcastle's Royalist army. -

Castlegate, York: Audience Research Pilot

CASTLEGATE, YORK: AUDIENCE RESEARCH PILOT PROJECT GEORGIOS ALEXOPOULOS INSTITUTE FOR THE PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF THE PAST, UNIVERSITY OF YORK APRIL 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................3 List of figures.................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction ...............................................................................................................5 1.1 Objectives ............................................................................................................5 1.2 Methodology........................................................................................................5 1.3 Potential for fulfilling long term objectives.........................................................6 2. Audience survey demographics.................................................................................6 2.1 Gender..................................................................................................................6 2.2 Age distribution ...................................................................................................7 2.3 Origin of respondents ..........................................................................................8 2.4 Educational background ......................................................................................8 2.5 Occupations .........................................................................................................9 -

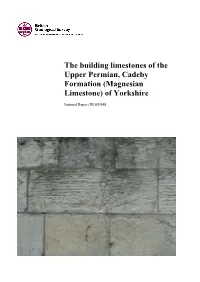

Magnesian Limestone) of Yorkshire

The building limestones of the Upper Permian, Cadeby Formation (Magnesian Limestone) of Yorkshire Internal Report IR/05/048 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/05/048 The building limestones of the Upper Permian, Cadeby Formation (Magnesian Limestone) of Yorkshire The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the G.K. Lott & A.H. Cooper Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number Licence No:100017897/5. Keywords Permian, building stones, Magnesian Limestone. Front cover Imbricated, laminated, rip-up clasts. Bibliographical reference LOTT, G.K. & COOPER, A.H. 2005. The building limestones of the Upper Permian, Cadeby Formation (Magnesian Limestone) of Yorkshire. British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/05/048. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected] You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2005. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2005 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Sales Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Desks. -

The Poor in England Steven King Is Reader in History at Contribution to the Historiography of Poverty, Combining As It Oxford Brookes University

king&t jkt 6/2/03 2:57 PM Page 1 Alannah Tomkins is Lecturer in History at ‘Each chapter is fluently written and deeply immersed in the University of Keele. primary sources. The work as a whole makes an original The poor in England Steven King is Reader in History at contribution to the historiography of poverty, combining as it Oxford Brookes University. does a high degree of scholarship with intellectual innovation.’ The poor Professor Anne Borsay, University of Wales, Swansea This fascinating collection of studies investigates English poverty in England between 1700 and 1850 and the ways in which the poor made ends meet. The phrase ‘economy of makeshifts’ has often been used to summarise the patchy, disparate and sometimes failing 1700–1850 strategies of the poor for material survival. Incomes or benefits derived through the ‘economy’ ranged from wages supported by under-employment via petty crime through to charity; however, An economy of makeshifts until now, discussions of this array of makeshifts usually fall short of answering vital questions about how and when the poor secured access to them. This book represents the single most significant attempt in print to supply the English ‘economy of makeshifts’ with a solid, empirical basis and to advance the concept of makeshifts from a vague but convenient label to a more precise yet inclusive definition. 1700–1850 Individual chapters written by some of the leading, emerging historians of welfare examine how advantages gained from access to common land, mobilisation of kinship support, crime, and other marginal resources could prop up struggling households. -

Creating the Slum: Representations of Poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate Districts of York, 1875-1914

Laura Harrison Ex Historia 61 Laura Harrison1 University of Leeds Creating the slum: representations of poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate districts of York, 1875-1914 In his first social survey of York, B. Seebohm Rowntree described the Walmgate and Hungate areas as ‘the largest poor district in the city’ comprising ‘some typical slum areas’.2 The York Medical Officer of Health condemned the small and fetid yards and alleyways that branched off the main Walmgate thoroughfare in his 1914 report, noting that ‘there are no amenities; it is an absolute slum’.3 Newspapers regularly denounced the behaviour of the area’s residents; reporting on notorious individuals and particular neighbourhoods, and in an 1892 report to the Watch Committee the Chief Constable put the case for more police officers on the account of Walmgate becoming increasingly ‘difficult to manage’.4 James Cave recalled when he was a child the police would only enter Hungate ‘in twos and threes’.5 The Hungate and Walmgate districts were the focus of social surveys and reports, they featured in complaints by sanitary inspectors and the police, and residents were prominent in court and newspaper reports. The area was repeatedly characterised as a slum, and its inhabitants as existing on the edge of acceptable living conditions and behaviour. Condemned as sanitary abominations, observers made explicit connections between the physical condition of these spaces and the moral behaviour of their 1 Laura ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Leeds, and recently submitted her thesis ‘Negotiating the meanings of space: leisure, courtship and the young working class of York, c.1880-1920’. -

Stay and Corset Makers. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Gate Stock And

YORK CLASSIFIED TRADES. 607 Smith Thos. Leadley, 74 Low Dougall John, M.B.C.M. Glasgow' Petergate 9 The Minster yard Smithson & Teasdale, 13 Lendal Draper Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., Spink H. H. 13 Spurriergate L.M., De Grey house, St. Thompson L. & W, Judge's court, Leonard's Coney st Dunhill C. H., M.D., Gray's court Twiner J. H. 12 Pavement Hewetson R M.RC.S. 36 Bootham Waddington Chas. 45 Stonegate Hill Alfred, Fishergate villa, Walker Wm. 18 Lendal Fishergate Ware Hy. John & Son, 6 New st Hood Wm., M.R.C.S., L.S.A., 28 Wilkinsen Wm. St. Helen's sq Castlegate Williamson Ed. Bland's court, 34 Jalland Wm. Hamerton, F.R.C.S., Coney st St. Leonard's house, 9 Museum Wood J. P. H. & J. R. & Co. 12 street Pavement Marshall John J. F., M.R.C.S., Young Robert, City chambers, 28 St. Saviourgate Clifford st Mills Bernard Langley, M.D., M.RO.S., 39 Blossom st Stay and Corset Makers. North Sam!. Wm., M.R.C.S., 84 Dillon Mrs. 8 Coney st Micklegate Foster Mrs. 14 Blossom st Oglesby Hy. N. 11 New York ter. WILKINSON, 60 Low Peter- Nunnery lane gate Petch Richard, M.D. Lon., 73 Wilkinson Thos. 33 North st Micklegate Walpole Sam!. 50 Goodramgate Preston H. M.D., 38 Bootham Ramsay Jas. 23 High Petergate Stock and Share Brokers. Renton Wm. M., M.R.C.S., M.D., Glaisby John, 14 Coney st 28 Grosvenor ter Guy G. H. Lendal Rose Robt. -

Roman York: from the Core to the Periphery

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD CLASS HERITAGE CONFERENCE, 2011 Sponsored by York Archaeological Forum Roman York, from the Core to the Periphery: an Introduction to the Big Picture Patrick Ottaway PJO Archaeology Introduction Amongst the objectives of the 2012 World Class Heritage conference was a review of some of the principal research themes in York’s archaeology in terms both of what had been achieved since the publication of the York Development and Archaeology Study in 1991 (the ‘Ove Arup Report’) and of what might be achieved in years to come. As far as the Roman period is concerned, one of the more important developments of the last twenty years may be found in the new opportunities for research into the relationship between, on the one hand, the fortress and principal civilian settlements, north-east and south-west of the Ouse, - ‘the core’ – and, on the other hand, the surrounding region, in particular a hinterland zone within c. 3-4 km of the city centre, roughly between the inner and outer ring roads – ‘the periphery’. This development represents one of the more successful outcomes from the list of recommended projects in the Ove Arup report, amongst which was ‘The Hinterland Survey’ (Project 7, p.33). Furthermore, it responds to the essay in the Technical Appendix to the Arup report in which Steve Roskams stresses that it is crucial to study York in its regional context if we are to understand it in relation to an ‘analysis of Roman imperialism’ (see also Roskams 1999). The use of the term ‘imperialism’ here gives a political edge to a historical process more often known as ‘Romanisation’ for which, in Britain, material culture is the principal evidence in respect of agriculture, religion, society, technology, the arts and so forth. -

Castle Piccadilly Conservation Area Appraisal 2006

rd Approved 23 March 2006 CONTENTS Preface Conservation Areas and Conservation Area Appraisals Introduction The Castle Piccadilly Conservation Area Appraisal 1. Location 1.1 Location and land uses within the area 1.2 The area’s location within the Central Historic Core Conservation Area 2. The Historical Development of the Area 2.1 The York Castle Area 2.2 The Walmgate Area 2.3 The River Foss 2.4 The Castlegate Area 3. The Special Architectural and Historic Characteristics of the Area 3.1 The York Castle Area 3.2 The Walmgate Area 3.3 The Castlegate Area 4. The Quality of Open Spaces and Natural Spaces within the Area 4.1 The River Foss 4.2 The York Castle Area 4.3 Tower Gardens 4.4 Other Areas 5. The Archaeological Significance of the Area 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Evidence from Archaeological Investigations 6. Relationships between different areas covered within the Appraisal 6.1 Views from within the area covered by the Appraisal 6.2 Views into the area covered by the Appraisal 6.3 The relative importance of the different parts of the area covered by this appraisal Conclusion Appendix 1. Listed Buildings within the Appraisal area CASTLE PICCADILLY CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1 PREFACE INTRODUCTION CONSERVATION AREAS AND THE CASTLE PICCADILLY CONSERVATION AREA CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL APPRAISALS This appraisal was approved by the City of York The legal definition of conservation areas as stated Council Planning Committee on 23rd March 2006 in Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings as an accompanying technical document to the and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 is: Castle Piccadilly Development Brief 2006, which is also produced by the City of York Council.