Community Cohesion and Village Pubs in Northern England: an Econometric Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

45 Hampden Street, Bishophill, York, YO1 6EA

45 Hampden Street, Bishophill, York, YO1 6EA Guide Price: £230,000 A beautiful 2 bedroom town house which has been the subject of updating works over recent years situated in the highly regarded Bishophill area. DESCRIPTION This tastefully presented two bedroom town house provides accommodation which would suite a variety of purchasers from investors wanting a property for holiday lets to owner occupiers alike. Located on the sought after Hampden Street, the home offers buyers the fantastic opportunity to live within the city walls and have access to the wide and varied amenities within York city centre and also close by on Micklegate. Having being recently updated, the accommodation briefly comprises: to the ground floor; entrance hall with stairs off, sitting room with understairs office area, refitted kitchen with integrated appliances and space for a dining table, inner hall with door leading to courtyard, bathroom with white suite. To the first floor; the stairs lead to the landing area and two bedrooms. OUTSIDE To the rear is the courtyard garden which is attractively presented offering the opportunity for alfresco dining, a rarity within the city centre. LOCAL AREA The Bishophill area of York lies within the City Walls and is a few minutes walk to both the City Centre and the railway station. It is also positioned on the west side of the centre allowing easy access out to the A64, Leeds and beyond. The amenities of Bishopthorpe Road and nearby river also add to the appeal of Yorks many bar, café and retail facilities on the doorstep. 3 High Petergate York North Yorkshire YO1 7EN T: 01904 653564 F: 01904 640067 E: [email protected] . -

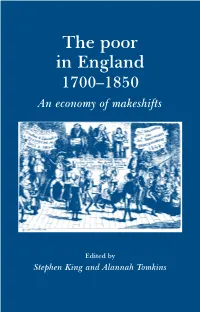

The Poor in England Steven King Is Reader in History at Contribution to the Historiography of Poverty, Combining As It Oxford Brookes University

king&t jkt 6/2/03 2:57 PM Page 1 Alannah Tomkins is Lecturer in History at ‘Each chapter is fluently written and deeply immersed in the University of Keele. primary sources. The work as a whole makes an original The poor in England Steven King is Reader in History at contribution to the historiography of poverty, combining as it Oxford Brookes University. does a high degree of scholarship with intellectual innovation.’ The poor Professor Anne Borsay, University of Wales, Swansea This fascinating collection of studies investigates English poverty in England between 1700 and 1850 and the ways in which the poor made ends meet. The phrase ‘economy of makeshifts’ has often been used to summarise the patchy, disparate and sometimes failing 1700–1850 strategies of the poor for material survival. Incomes or benefits derived through the ‘economy’ ranged from wages supported by under-employment via petty crime through to charity; however, An economy of makeshifts until now, discussions of this array of makeshifts usually fall short of answering vital questions about how and when the poor secured access to them. This book represents the single most significant attempt in print to supply the English ‘economy of makeshifts’ with a solid, empirical basis and to advance the concept of makeshifts from a vague but convenient label to a more precise yet inclusive definition. 1700–1850 Individual chapters written by some of the leading, emerging historians of welfare examine how advantages gained from access to common land, mobilisation of kinship support, crime, and other marginal resources could prop up struggling households. -

Creating the Slum: Representations of Poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate Districts of York, 1875-1914

Laura Harrison Ex Historia 61 Laura Harrison1 University of Leeds Creating the slum: representations of poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate districts of York, 1875-1914 In his first social survey of York, B. Seebohm Rowntree described the Walmgate and Hungate areas as ‘the largest poor district in the city’ comprising ‘some typical slum areas’.2 The York Medical Officer of Health condemned the small and fetid yards and alleyways that branched off the main Walmgate thoroughfare in his 1914 report, noting that ‘there are no amenities; it is an absolute slum’.3 Newspapers regularly denounced the behaviour of the area’s residents; reporting on notorious individuals and particular neighbourhoods, and in an 1892 report to the Watch Committee the Chief Constable put the case for more police officers on the account of Walmgate becoming increasingly ‘difficult to manage’.4 James Cave recalled when he was a child the police would only enter Hungate ‘in twos and threes’.5 The Hungate and Walmgate districts were the focus of social surveys and reports, they featured in complaints by sanitary inspectors and the police, and residents were prominent in court and newspaper reports. The area was repeatedly characterised as a slum, and its inhabitants as existing on the edge of acceptable living conditions and behaviour. Condemned as sanitary abominations, observers made explicit connections between the physical condition of these spaces and the moral behaviour of their 1 Laura ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Leeds, and recently submitted her thesis ‘Negotiating the meanings of space: leisure, courtship and the young working class of York, c.1880-1920’. -

Roman York: from the Core to the Periphery

PROCEEDINGS OF THE WORLD CLASS HERITAGE CONFERENCE, 2011 Sponsored by York Archaeological Forum Roman York, from the Core to the Periphery: an Introduction to the Big Picture Patrick Ottaway PJO Archaeology Introduction Amongst the objectives of the 2012 World Class Heritage conference was a review of some of the principal research themes in York’s archaeology in terms both of what had been achieved since the publication of the York Development and Archaeology Study in 1991 (the ‘Ove Arup Report’) and of what might be achieved in years to come. As far as the Roman period is concerned, one of the more important developments of the last twenty years may be found in the new opportunities for research into the relationship between, on the one hand, the fortress and principal civilian settlements, north-east and south-west of the Ouse, - ‘the core’ – and, on the other hand, the surrounding region, in particular a hinterland zone within c. 3-4 km of the city centre, roughly between the inner and outer ring roads – ‘the periphery’. This development represents one of the more successful outcomes from the list of recommended projects in the Ove Arup report, amongst which was ‘The Hinterland Survey’ (Project 7, p.33). Furthermore, it responds to the essay in the Technical Appendix to the Arup report in which Steve Roskams stresses that it is crucial to study York in its regional context if we are to understand it in relation to an ‘analysis of Roman imperialism’ (see also Roskams 1999). The use of the term ‘imperialism’ here gives a political edge to a historical process more often known as ‘Romanisation’ for which, in Britain, material culture is the principal evidence in respect of agriculture, religion, society, technology, the arts and so forth. -

Conservation Bulletin 32.Rtf

Conservation Bulletin, Issue 32, July 1997 Planning change in London 1 Editorial: a new Government 3 Grant aid offered in 1996/7 4 The future for archaeology 8 Roofs of England 10 Planning and listing directions issued 11 Post-war and thematic listing 12 Long-term planning for Ironbridge Gorge 14 New Chief Executive for EH 16 Perspectives on sustainability 16 The Shimizu case 17 Books and Notes 18,20 Defining archaeological finds 22 Appraising conservation areas 24 (NB: page numbers are those of the original publication) London: planning change in a world city Antoine Grumbach’s design for an inhabited bridge across the Thames was joint winner of the recent ‘Living Bridges’ exhibition at the Royal Academy Tall buildings. New Thames bridges. Better architecture. A new planning policy for London. These four topics were the focus of an English Heritage debate held on 29 May before an invited audience of developers, architects, journalists and policy makers at the Royal College of Physicians. Philip Davies reports ‘London – planning change in a world city’, chaired by the broadcaster and journalist Kirsty Wark, provided a rare opportunity for some of London’s key figures to discuss the future of London and to set out their vision for the capital. The Challenge London faces serious challenges to its distinctive character. Plans for towers of an unprecedented scale and height, and for new and enlarged bridges across the Thames, could change forever the way the city looks and functions. Successive surveys have confirmed that people and businesses are attracted to London not only as the centre of government, communications and financial expertise, but also because it has retained its sense of history and the diversity of its built heritage. -

Parish Records of York, St. Mary, Bishophill, Senior

Parish Records of York, St. Mary, Bishophill, Senior Finding Aid PR PARISH RECORDS (on deposit) YORK ST MARY BISHOPHILL SENIOR Now deanery of the City of York Y/M Bp. S. contents 1-13 Registers 14 Voluntary subscription book 15-23 Various minutes and acoounts books 24 Loose minutes, St Clements 25 Citations, faculties, licences, mortgages and conveyances 26 Terriers 27 Tithes 28 Statistical returns of parochial work and other documents relating to work in the parish 29 Marriage licences 30 Income of benefice and other Rector's correspondence and papers 31 Correspondence and papers re St Clement's Parish Hall 32 London Gazettes 33 Schools Managers' Records, Cherry Street Schools 34 Churchwardens' correspondence and papers 35 Churchwardens' vouchers (general) 36 Churchwardens' vouchers (charity bread) 37 Churchwardens' vouchers (charity coal) 38 Poor law and charities' deeds, papers and accounts (see also 36, 37 above, and 39 below) 39 Barstow Trust records 40 Miscellaneous items 41 Cameron Walker Trust Records 42-44 Charities 45 Gas bill 1935 46 Sunday School 47 Account 48-51 Terriers 52 Bundle of letters re parish boundaries 53-54 Tithe, land tax 55 Faculty re bells r-c.c.;c:-.(a..s• 0,41, PR PARISH RECORDS (on deposit) YORK ST MARY BISHOPHILL SENIOR Now deanery of the City of York Y/M Bp. S. 1-13 Registers 1 1598-1726 2 1727-1782 (marriages to 1753) 3 Baptisms and burials 1782-1812 4 Baptisms 1813-1840 5 Baptisms 1841-1871 6 Baptisms 1871-1885 and 1892-1897 7 Baptisms 1885-1892 [not deposited but referred to in no. -

Batchelor 204054437 Urbi Et Suburbi Wret Text.Pdf

URBI ET SUBURBI: The landscape and settlement of York, south-west of the river Ouse, between the 9th and 16th centuries. Simon Batchelor. BA(Hons), MA Master of Arts by Research in Archaeological Studies University of York. Archaeology. March 2020 Abstract: The purpose of this dissertation is to examine the landscape and settlement of a little understood area of the city of York. Drawing on archaeological data and landscape analysis it aims to present a picture of how this area developed between the mid-9th and mid-16th centuries. Archaeological data is drawn from those excavations which reached period appropriate deposits, whilst landscape data is drawn from maps, plans, photographs and documentary sources. GIS software and historic maps have been used to illustrate this development. Evidence from earlier periods will also be outlined in order to illustrate their influence, if any, upon the medieval landscape. 2 Contents: Abstract 2 List of Contents 3 Abbreviations 3 List of Maps 4 List of Plates 5 Acknowledgements. 6 Declaration 6 Chapter 1: Introduction to Urban and Landscape Studies. 7 Chapter 2: Sources of Evidence and Methodology. 14 Chapter 3: Zone 1: Bishophill Senior, The Urban Core. 22 Chapter 4: Zone 2: Clementhorpe, The Suburb. 38 Chapter 5: Zone 3: Middlethorpe, The Rural Hinterland. 45 Chapter 6: Landscape and Settlement. 52 Chapter 7: Final thoughts and questions arising. 68 Bibliography. 76 Abbreviations RCHM(E) Royal Commission for Historic Monuments (England) VCH Victoria County History YAT York Archaeological Trust YATGAZ YAT archive of archaeology (online resource) YCHCCAA York Central Historic Core Conservation Area Appraisal. YHECP York Historic Environment Characterisation Project. -

St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate L

The Archaeology of York Anglo-Scandinavian York 8/2 St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate L. P. Wenham, R. A. Hall, C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker Published for the York Archaeological Trust 1987 by the Council for British Archaeology The Archaeology of York Volume 8: Anglo-Scandinavian York General Editor P.V. Addyman Co-ordinating Editor V. E Black ©York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research 1987 First published by Council for British Archaeology ISBN 0 906780 68 3 Cover illustration: St Mary Bishophill Junior, opening in east elevation of belfry. Drawing by Terry Finnemore Digital edition produced by Lesley Collett, 2011 Volume 8 Fascicule 2 St Mary Bishophill Junior and St Mary Castlegate By L. P. Wenham, R. A. Hall, C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker Contents St Mary Bishophill Junior ........................................................................................74 Excavation to the North of the Church by L. P. Wenham and R. A. Hall. ..................................................................................75 Introduction ............................................................................................................75 The excavated sequence ..........................................................................................76 Conclusions ............................................................................................................81 The Tower of the Church of St Mary Bishophill Junior by C. M. Briden and D. A. Stocker. .............................................................................84 -

Excavations by York Archaeological Trust Within the Walled Area to the South-West of the River Ouse, York

YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST EXCAVATIONS BY YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST WITHIN THE WALLED AREA TO THE SOUTH-WEST OF THE RIVER OUSE, YORK By J.M. McComish WEB BASED REPORT Report Number 2015/48 September 2015 YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST York Archaeological Trust undertakes a wide range of urban and rural archaeological consultancies, surveys, evaluations, assessments and excavations for commercial, academic and charitable clients. We manage projects, provide professional advice and fieldwork to ensure a high quality, cost effective archaeological and heritage service. Our staff have a considerable depth and variety of professional experience and an international reputation for research, development and maximising the public, educational and commercial benefits of archaeology. Based in York, Sheffield, Nottingham and Glasgow the Trust’s services are available throughout Britain and beyond. York Archaeological Trust, Cuthbert Morrell House, 47 Aldwark, York YO1 7BX Phone: +44 (0)1904 663000 Fax: +44 (0)1904 663024 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.yorkarchaeology.co.uk © 2015 York Archaeological Trust for Excavation and Research Limited Registered Office: 47 Aldwark, York YO1 7BX A Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England No. 1430801 A registered Charity in England & Wales (No. 509060) and Scotland (No. SCO42846) York Archaeological Trust 3 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 4 2 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................ 4 3 HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND .......................................................... 5 3.1 The history of York in the Roman and Anglian periods ...................................................... 5 3.2 Roman and Anglian remains observed/found from the 18 th to mid-20 th century ............... 7 4 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FOR THE CIVILIAN SETTLEMENT ...................................... 8 4.1 The founding of the fortress to c. -

Alternative York

Within these pages you’ll find the story of the York “they” don’t want to tell you about. Music, poets, : football and beer along with fights RK for women’s rights and Gay YO Liberation – just the story of AWALK another Friday night in York in fact! ONTHEWILDSIDE tales of riot, rebellion and revolution Paul Furness In association with the York Alternative History Group 23 22 24 ate ierg 20 Coll 21 e at 25 rg The Minster te Pe w 19 Lo 13 12 et 18 Stre 14 Blake y 17 one 15 C t ree 16 St St at R io o n ad York: The route oss r F ive lly R 3 t di e a 2 e cc r Pi t 5 S Clifford’s 4 r e w Tower o 1 T 26 Finish Start e t a g e s u O h g i H 11 6 e gat River Ouse lder Ske 7 e t a r g io l en e ill S k oph c h i Bis M 8 10 9 Contents Different Cities, Different Stories 4 Stops on the walk: 1 A bloody, oppressive history… 6 2 Marching against ‘Yorkshire Slavery’ 9 3 Yorkshire’s Guantanamo 10 4 Scotland, the Luddites and Peterloo 12 5 The judicial murder of General Ludd 14 6 “Shoe Jews” and the Mystery Plays 16 7 Whatever happened to Moby Dick? 18 8 Sex and the City 19 9 The Feminist Fashionista! 21 10 The York Virtuosi 23 11 Gay’s the Word! 24 12 Poets Corner 27 13 Votes for Women! 29 14 Where there’s muck… 30 15 Doctor Slop and George Stubbs 32 16 Hey Hey Red Rhino! 33 17 It’s not all Baroque and Early Music! 35 18 A Clash of Arms 36 19 An Irish Poet and the Yorkshire Miners 37 20 Racism treads the boards 38 21 Lesbian wedding bells! 40 22 The World Turned Upside Down 43 23 William Baines and the Silent Screen 45 24 Chartism, football and beer… -

Bibliography of Stained Glass in York City Churches (Excluding York Minster)

Bibliography of Stained Glass in York City Churches (excluding York Minster) General Manuscript Sources Cambridge, Trinity College MS 0. 4. 33: H. Keep, Monumenta Eboracensia, 1681 London, Victoria & Albert Museum, National Art Library, MSS 86. BB. 50–51: J. W. Knowles, Stained Glass in the York Churches, 2 vols, c. 1890–1920 Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Top. Yorks. C. 14: Henry Johnston, 1669–70 York, City Reference Library, MS Y040 1935. 9. J. W. Knowles, York Churches, c. 1890- 1920 York, King’s Manor Library, University of York: Peter Newton Archive York, King’s Manor Library, University of York: photograph and slide collections York, York Minster Library, MS L1 (8): James Torre, Antiquities Ecclesiastical of the City of York, c. 1691 Published Sources M. D. Anderson, The Imagery of British Churches, London, 1955 —, Drama and Imagery in English Medieval Churches, Cambridge, 1963 H. Arnold and L. B. Saint, Stained Glass of the Middle Ages in England and France, London 1913 [esp. chps 10 ‘Fourteenth-Century Glass at York’ and 15 ‘Fifteenth Century Glass at York’] A. Barclay, Views of the Parish Churches in York, with a Short Account of Each, York, 1831 C. M. Barnett, ‘Commemoration in the Parish Church: Identity and Social Class in Late Medieval York’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, lxxii, 2000, pp. 73–92 —, ‘Memorials and Commemoration in the Parish Churches of Late Medieval York’, PhD thesis, University of York, 1997 J. N. Bartlett, ‘The Expansion and Decline of York in the Later Middle Ages’, Economic History Review, 12, 1959–60, pp. 17–33 P. Barnham, C. Cross and A.