Institutional Responses to Pressures for Sustainable Palm Oil Stephen Marks Pomona College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Request for Consideration of the Situation of Indigenous Peoples In

Request for Consideration of the Situation of Indigenous Peoples in Kalimantan, Indonesia, under the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination’s Urgent Action and Early Warning Procedures Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Seventy-First Session 30 July – 18 August 2007 Submitted by Perkumpulan Sawit Watch Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara/AMAN (Indigenous People Alliance of the Archipelago) Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Kalimantan Barat (Indigenous People Alliance of West Kalimantan) Lembaga Studi dan Advokasi Masyarakat/ELSAM (Center for Community Study and Advocacy) Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia/WALHI (Friends of the Earth Indonesia) Perkumpulan Untuk Pembaharuan Hukum Berbasis Masyarakat dan Ekologis/HuMA (Association for Community- and Ecologically-based Legal Reform) Yayasan Padi Indonesia Lembaga Bela Banua Talino Lembaga Gemawan (Lembaga Pengembangan Masyarakat Swandiri/The Institution of Swandiri Society Empowerment) Institut Dayakologi Forest Peoples Programme 6 July 2007 Contents Page Executive Summary 1 Submitting Organizations 4 I. INTRODUCTION 6 II. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN INDONESIA 8 III. OIL PALM PLANTATIONS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ 10 RIGHTS IV. PERSISTENT VIOLATION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES' 11 RIGHTS IN KALIMANTAN V. INDONESIA IS IN THE ADVANCED STAGES OF ESTABLISHING MASSIVE PALM OIL PLANTATIONS IN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ TRADITIONAL TERRITORIES IN 13 KALIMANTAN VI. INDONESIAN LAW DISCRIMINATES AGAINST INDIGENOUS 17 PEOPLES A. The Constitution 17 B. The Basic Agrarian Law 18 C. The 1999 Forestry Act 19 D. The 2004 Plantation Act 20 VII. REQUEST 22 VIII. ANNEXES 23 A. ‘President Admits Indigenous People Mistreated’, Jakarta Post, 10 August 24 2006 B. Oil Palm and Other Commercial Tree Plantations, Mono-cropping: 25 Impacts on Indigenous Peoples’ Land Tenure and Resource Management Systems and Livelihoods, UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues Working Paper, E/C.19/2007/CRP.6 C. -

Oil Palm Plantations and Transboundary Haze: Patronage Networks and Land

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UM Digital Repository HELENA VARKKEY POST-PRINT WETLANDS 1 Oil Palm Plantations and Transboundary Haze: Patronage Networks and Land 2 Licensing in Indonesia’s Peatlands 3 Helena Varkkey 4 5 Department of International and Strategic Studies, University of Malaya, 50603, Kuala 6 Lumpur, Malaysia 7 Email: [email protected] 8 Tel: +60123162146 9 Fax: +60323008318 10 1 HELENA VARKKEY POST-PRINT WETLANDS 11 Oil Palm Plantations and Transboundary Haze: Patronage Networks and Land 12 Licensing in Indonesia’s Peatlands 13 By HELENA VARKKEY 14 15 Peatlands in Indonesia are protected by regulations that forbid the conversion of these lands 16 into plantations. However, peat fires here have been found to be a major source of smoke that 17 travels across national boundaries creating regional haze. Despite these regulations, more 18 than a quarter of all Indonesian oil palm plantations are on peat. This paper argues that 19 patronage networks within the Indonesian oil palm sector have been a major factor in the 20 unsustainable use of peatlands there. Rampant patronage politics have made it easy for well- 21 connected companies to skirt regulations to obtain licenses for these lands. Decentralization 22 has further encouraged this practice at the regional level, as regional elites are eager to reap 23 the benefits of local investments. In addition, clients are able to exert their influence over 24 state decision-making to ensure that any changes to the licensing process does not jeopardize 25 their access to these lands. -

Parent Mill Mill Name Latitude Longitude Country Aa Sawit Siang

PepsiCo Palm Oil Mill List 2018 The following list is of mills that were in our supply chain in 2018 and does not necessarily reflect mills that are supplying or will supply PepsiCo in 2019. Some of these mills are associated with ongoing complaints that have been registered in our Grievance Mechanism and are being managed through our grievance process. The following palm oil mill list is based on information that has been self-reported to us by suppliers and has only been partially independently verified (see our Palm Oil Progress Report for more information). Though we have made considerable effort to validate the data, we cannot guarantee its full accuracy or completeness. Parent Mill Mill Name Latitude Longitude Country Aa Sawit Siang 1.545386 104.209347 Malaysia Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 Indonesia Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2 2.11272 100.27311 Indonesia Ace Oil Mill Ace Oil Mill 2.91192 102.77981 Malaysia Aceites Aceites Cimarrones 3.035593889 -73.11146556 Colombia Aceites De Palma Aceites De Palma 18.0470389 -94.91766389 Mexico Aceites Manuelita Yaguarito 3.883139 -73.339917 Colombia Aceites Manuelita Manavire 3.937706 -73.36539 Colombia Aceites Sustentables De Palma Aceites Sustentables De Palma 16.360506 -90.467794 Mexico Achi Jaya Plantations Johor Labis 2.251472222 103.0513056 Malaysia Adimulia Agrolestari Singingi -0.205611 101.318944 Indonesia Adimulia Agrolestari Segati -0.108983 101.386783 Indonesia Adimulia Palmo Lestari Adimulia Palmo Lestari -1.705469 102.867739 -

Key Sustainability Issues in the Palm Oil Sector

Key Sustainability Issues in the Palm Oil Sector A Discussion Paper for Multi-Stakeholders Consultations (commissioned by the World Bank Group) By Cheng Hai Teoh THE WORLD BANK Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this discussion draft do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group or its member governments. The World Bank Group does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this draft and accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any consequence of their use. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this draft do not imply on the part of the World Bank Group any judgment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Table of Contents A. Introduction ................................................................................................... 2 Background ............................................................................................................ 2 Objectives .............................................................................................................. 2 Approach ............................................................................................................... 3 B. Overview of the Palm Oil Sector ..................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 4 Development of the palm oil sector .......................................................................... -

Suspended Unilever Palm Oil Suppliers and Growers (With Mill List)

Suspended Palm Oil Direct Suppliers or Oil Palm Growers by Unilever Updated September 2020 The list below provides information of previous direct palm oil suppliers or indirect oil palm growers that have been suspended from Unilever’s supply chain due to grievances brought to our attention alleging non-compliance against the Unilever Sustainable Palm Oil Sourcing Policy (“USPOSP”) and/or Unilever’s Responsible Sourcing Policy or due to the fact that it could not be confirmed that these companies were in compliance with the USPOSP at the group level. The list of palm oil mills associated with these companies but were declared by our suppliers in 2019 can be found in the Suspended Palm Oil Mills list of this document. The main purpose of this list is to ensure that Unilever’s direct palm oil suppliers understand Unilever’s palm oil suspension list and that palm oil, palm kernel oil, and their derivatives do not enter Unilever’s supply chain from these companies. We are working with our suppliers to ensure that these companies and mills (at a group level) are not be part of our supply chain unless compliance towards the USPOSP and Responsible Sourcing Policy can be verified or appropriate remediation plans for non-compliance have been agreed and are implemented. A list of grievances that have been raised to Unilever with regard to our palm oil supply chain can be found in Unilever’s Palm Oil Grievance Tracker. Please note that we are not making any accusations of legal wrongdoing but are sharing that we have sight of data that indicates that certain supply sources are not in accordance with the USPOSP. -

How a Leading RSPO Palm Oil Producer Is Clearing Peatland Tiger

How a leading RSPO palm oil producer is clearing peatland tiger habitat covered by Indonesia’s moratorium on deforestation This crime file reveals the ongoing rogue activities of one of Indonesia’s largest palm oil producers, the Darmex Agro group – generally known as ‘Duta Palma’ – whose illegal and destructive operations were first exposed by Greenpeace International in 2007. While some companies in the sector are seizing the initiative and setting an example of zero deforestation development, the activities of rogue operators such as Duta Palma serve as an example of practices that the palm oil industry must put behind it. Other stakeholders, from government to end users, must show that they will no longer tolerate flagrant legal abuse and environmental destruction. A DIRTYA BUSINESS b Contents Introduction 2 Duta Palma: a pedigree of illegality 4 Background 4 Duta Palma’s operations in Riau 4 Recent investigations: Duta Palma still flouting the law 10 Failures of governance 12 The Indonesian government 14 The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil 16 Other efforts to ensure responsible palm oil production 18 Time for action Producers 20 Traders 20 Corporate consumers 20 Financial sector 20 Indonesian government 21 Cover: PT Palma Satu, Indragiri Hulu, RSPO 21 Riau, September 2011: An excavator clearing peatland forest; 0°34’06.6”S 102°38’40.8”E. Endnotes 22 ©Ifansasti/Greenpeace Here: Duta Palma concessions, Indragiri Bibliography 24 Hulu, Riau, October 2007: Drainage canal a nd recent peatland rainforest clearance in a palm oil concession in Riau owned by the Duta Palma group. ©Budhi/Greenpeace A DIRTYA BUSINESS 1 Introduction Indonesia’s rainforests are under threat from some of the users such as Nestlé have committed themselves to most destructive companies within one of the world’s zero deforestation in their supply chains, working with fastest growing industries. -

Mill List - 2020

General Mills - Mill List - 2020 General Mills July 2020 - December 2020 Parent Mill Name Latitude Longitude RSPO Country State or Province District UML ID 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 3F Oil Palm Agrotech 17.00352 81.46973 No India Andhra Pradesh West Godavari PO1000008590 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2.051269 100.252339 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000004269 Aathi Bagawathi Manufacturing Abdi Budi Mulia 2 2.11272 100.27311 No Indonesia Sumatera Utara Labuhanbatu Selatan PO1000008154 Abago Extractora Braganza 4.286556 -72.134083 No Colombia Meta Puerto Gaitán PO1000008347 Ace Oil Mill Ace Oil Mill 2.91192 102.77981 No Malaysia Pahang Rompin PO1000003712 Aceites De Palma Aceites De Palma 18.0470389 -94.91766389 No Mexico Veracruz Hueyapan de Ocampo PO1000004765 Aceites Morichal Aceites Morichal 3.92985 -73.242775 No Colombia Meta San Carlos de Guaroa PO1000003988 Aceites Sustentables De Palma Aceites Sustentables De Palma 16.360506 -90.467794 No Mexico Chiapas Ocosingo PO1000008341 Achi Jaya Plantations Johor Labis 2.251472222 103.0513056 No Malaysia Johor Segamat PO1000003713 Adimulia Agrolestari Segati -0.108983 101.386783 No Indonesia Riau Kampar PO1000004351 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Sei Basau) -0.136967 101.3908 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000004358 Adimulia Agrolestari Surya Agrolika Reksa (Singingi) -0.205611 101.318944 No Indonesia Riau Kuantan Singingi PO1000007629 ADIMULIA AGROLESTARI SEI TESO 0.11065 101.38678 NO INDONESIA Adimulia Palmo Lestari Adimulia Palmo Lestari -

How the Palm Oil Industry Is Cooking the Climate

HOW THE PALM OIL INDUSTRY IS COOKING THE CLIMATE www.greenpeace.org ii ‘Climatechangeismarket failureonthegreatest scaletheworldhasseen. Itresultsfromthefactthat thecostsofgreenhouse gasemissionsarenot paidforbythosewho createtheemissions.’ 2007 King Review for the UK Government Treasury iii CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 TICK TICK TICK … 8 FORESTS AS TICKING CLIMATE BOMBS 8 PEAT: A VOLATILE MATERIAL 16 RIAU: A LIT FUSE 22 DUTA PALMA: THE OIL PALM INDUSTRY’S RECIPE FOR CLIMATE DISASTER 38 WHO CONTROLS THE TRADE? 38 UNILEVER – RSPO PRESIDENT 38 UNILEVER’S SUPPLIERS – CARGILL, ADM-KUOK-WILMAR, GOLDEN HOPE AND SINAR MAS 38 WHAT THE COMMODITY TRADERS ARE AddING TO THE MIX 40 MAJOR NAMES IN THE FOOD INDUSTRY ARE USING TAINTED PALM OIL 46 PROCTER & GAMBLE USES NEARLY 1% OF GLOBAL PALM OIL PRODUCTION 46 NESTLÉ TRADING WITH CARGILL 46 KRAFT AND A LOAD OF OTHER WORLD LEADERS IN THE 47 FOOD INDUSTRY HAVE THEIR FINGERS IN THE PALM OIL PIE BIOFUELING RAINFOREST DESTRUCTION 50 CLIMATE CHANGE – A BRAND NEW MARKETING OPPORTUNITY FOR PALM OIL 52 LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR FOREST DESTRUCTION 53 TODAY’S EMPIRE BUILDING, TOMORROW’S DOWNFALL 55 EMISSIONS EXPLOSION – DUTA PALMA’S SMOKING GUN 56 DEFUSE OR DETONATE? 58 TIME FOR ACTION 59 STOP THE PROBLEM: ZERO DEFORESTATION 61 START THE SOLUTION: CLIMATE PROTECTION START THE SOLUTION: CUT ONGOING EMISSIONS ENDNOTES 64 reFerenCes 73 ACronYMS, teCHNICAL terMS, etC 79 CREDITS 81 iv 1997: HAZE OVER INDONESIA Uncontrollable fires in forests and peatlands during 1997 released up to 2.57Gt of carbon, a volume equivalent to up to 40% of the mean annual global carbon emissions from fossil fuels during the period. -

Illegalities in Forest Clearance for Large-Scale Commercial Plantations

Indonesia: Illegalities in Forest Clearance for Large-Scale Commercial Plantations Eric Wakker, Aidenvironment Asia June 2014 With Support from: Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Oil Palm ................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Project History and Key Developing Institutions ................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Major Companies Involved ................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.3 Forest Loss ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.4 Main Expansion Areas ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 2.5 Future Expansion Plans ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Industrial Tree Plantations .................................................................................................................. 8 3.1 History ................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Patronage Politics, Plantation Fires and Transboundary Haze by HELENA VARKKEY

HELENA VARKKEY PRE-PRINT ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS Patronage politics, plantation fires and transboundary haze By HELENA VARKKEY Since 1982, haze pollution has become an almost annual occurrence in Southeast Asia, with the worst episodes being in the period of 1997–1998 and in 2006–2007. Haze originates from peat and forest fires, mostly in Indonesia. The negative effects of haze can be observed at the global level, with increased carbon emissions exacerbating climate change, and more importantly at the regional level, with serious environmental and socioeconomic effects in Indonesia and its neighbouring countries. Most of these fires are manmade, and can be traced back to land clearing activities of commercial oil palm plantations. This article questions why these companies have been able to burn with such impunity, even though using fire for land clearing is against Indonesian law. It argues that local and foreign plantation companies have cultivated strong patronage linkages with key patrons among the ruling elite. Hence, patrons are encouraged to protect their clients from the repercussions of their actions. This weakens the power of the state in terms of law enforcement, where national laws against the use of fire are thus rendered useless in the face of powerful economic interests. Well-connected companies therefore continue to use fire as a cost-efficient way to clear land while disregarding its serious environmental and socioeconomic implications. Keywords: haze pollution; forest fires; oil palm; Indonesia; patronage; environmental law 1 HELENA VARKKEY PRE-PRINT ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS Patronage politics, plantation fires and transboundary haze Introduction Haze is defined as ‘sufficient smoke, dust, moisture, and vapour suspended in air to impair visibility’. -

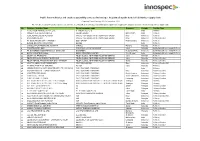

Public List of Refineries and Crushers Potentially Connected to Innospec Inc Palm Oil & Palm Kernel Oil Derivatives Supply Chain

Public list of refineries and crushers potentially connected to Innospec Inc palm oil & palm kernel oil derivatives supply chain Reporting Period: January 2020 – December 2020 The 89 refineries and 57 crushers disclosed below have been identified via an independent third party supply chain mapping investigation and connected to Innospec Inc’s supply chain. No. Refinery / Crusher Name Parent company name Province Country Facility Type 1 3F OIL PALM AGROTECH PVT. LTD. 3F INDUSTRIES LTD - India Refinery 2 FRIGORIFICO ALLANA LIMITED ALLANA GROUP Maharashtra India Refinery 3 CEMERLANG ENERGI PERKASA APICAL / AAA OILS & FATS / ASIAN AGRI GROUP Riau Indonesia Refinery 4 SARI DUMAI SEJATI APICAL / AAA OILS & FATS / ASIAN AGRI GROUP Riau Indonesia Refinery/Crusher 5 PT. BERLIAN EKA SAKTI TANGGUH BEST GROUP North Sumatra Indonesia Refinery 6 BUNGE INDIA PRIVATE LIMITED BUNGE - India Refinery 7 CARGILL PALM PRODUCTS, KUANTAN CARGILL Pahang Malaysia Refinery 8 CAROTINO SDN. BHD. CAROTINO / JC CHANG GROUP Johor Malaysia Surfactants/Oleochemicals/Refinery 9 PT. ECOGREEN OLEOCHEMICALS - Batam plant ECOGREEN Kepulauan Riau Indonesia Surfactants/Oleochemicals/Refinery 10 EMAMI AGROTECH, Haldia EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED West Bengal India Surfactants/Oleochemicals/Refinery 11 DELIMA OIL PRODUCTS FELDA GLOBAL VENTURES HOLDINGS BERHAD Johor Malaysia Refinery 12 FELDA IFFCO OIL PRODUCTS SDN BHD FELDA GLOBAL VENTURES HOLDINGS BERHAD Johor Malaysia Refinery/Crusher 13 FELDA KERNEL PRODUCTS SDN BHD - SAHABAT FELDA GLOBAL VENTURES HOLDINGS BERHAD Sabah Malaysia Refinery/Crusher -

Draft for Internal Review

AAK Lags in Implementation of NDPE Best Practices Chain Reaction Research is a collaborative effort of: January 2019 Aidenvironment Climate Advisers Profundo AAK is a vegetable oils producer, with its headquarters in Malmö, Sweden. The company has 20 production facilities worldwide, sales offices in more than 25 countries 1320 19th Street NW, Suite 300 and a total workforce of 3,500 employees. In 2017, its revenue was equivalent to USD Washington, DC 20036 3.2 billion in 2017. Within the world’s palm oil supply chain, AAK is positioned United States www.chainreactionresearch.com midstream between the largest palm oil refiners/traders and the largest consumer [email protected] goods companies. The company’s No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) strategy relies on meaningful action from the traders and refiners that supply AAK with Authors: refined palm oil. This approach fails to follow industry best practices. Albert ten Kate - Aidenvironment Alexandra Christopoulou – Profundo Matt Piotrowski - Climate Advisors Key Findings With contributions from: • AAK processes various vegetable oils, including 1.7 percent of the world’s palm Gerard Rijk - Profundo Tim Steinweg - Aidenvironment oil. AAK handled, traded and processed 1.3 million tonnes of palm oil in 2017, a 53 percent increase from 2013 (0.84 million). AAK primarily purchases refined palm oil, which it processes into specialized vegetable oils and fats for consumer goods products. Consumer goods companies that buy palm oil products from AAK include Unilever, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Mondelēz International, Kraft Heinz, General Mills, Mars, Danone and the Hershey Company. • AAK has a group policy on sustainable palm oil and commits to HCV and HCS standards.