Model of Inter-Municipal Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Public Transport Service Co-Creation: Leveraging Passenger’S Knowledge to Enhance Travel Experience

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 111 ( 2014 ) 577 – 585 EWGT2013 – 16th Meeting of the EURO Working Group on Transportation Urban public transport service co-creation: leveraging passenger’s knowledge to enhance travel experience António A. Nunesa,*, Teresa Galvãoa, João Falcão e Cunhaa aFaculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto, Rua Dr. Roberto Frias, 4200-465 Porto, Portugal Abstract Mobile devices are increasingly pervasive and are transforming information distribution paradigms. A rapidly growing segment of urban public transport passengers carry mobile computing devices, permanently and on the move. In a context of thinning financial resources, getting customers involved in the actual delivery of a public transport service as real-time information consumers and providers, may be a powerful method to enhance travel experience while reducing operational costs for the service operator. Each and every customer travelling on a public transport network has unique knowledge about the service operation as it unfolds. This paper proposes a framework that aims to unify public transport passengers’ collective intelligence through crowdsourcing, using their mobile computing devices and dedicated web services. It strives to intensify win-win relationships between public transport passengers and operators. The structured exchange of information is sustained by a validation mechanism for data reliability, and an incentive mechanism to encourage passenger participation. Passengers benefit from rich real-time data tailored to their profiles, to ease their journeys and improve travel experience, in exchange for their own participation providing and validating information. Operators gain access to rich customer generated data, which in an aggregated format may provide a real-time assessment of customer experience and of local performance across the entire network operation. -

Emta News N°25

EUROPEAN METROPOLITAN TRANSPORT AUTHORITIES July 2006 - n° 25 News from Europe G Political agreement on the revised approve the modifications of the text • A methodology for smart charging for proposal for a regulation of PSO in adopted by the Council compared to the infrastructure (2008) public transport initial version of the Commission: The new • The start of Galileo concession (2009) The Council reached a political agreement text takes better in account remarks made on the revised proposal for a regulation on by most of public transport actors regarding Urban transport seems to be better taken in public service obligations for passenger the restrictive definition of internal operators, account compared to the 2001 White Paper transport services by rail and by road, publi- their strict geographical containment or the (see EMTA position on the mid-term review shed by EU Commission on 20 July 2005. maximum duration for contracts including on our website) and EMTA looks forward to The text as agreed will be adopted as a construction of infrastructures. EMTA position contribute to the 2007 Green Paper. common position at a forthcoming Council on the Commission’s proposal is available on ec.europa.eu/transport/transport_policy_revie session under Finnish Presidency and sent to EMTA website, section publications. w/index_en.htm the European Parliament with a view of the www.consilium.europa.eu second reading next Autumn. www.emta.com/article.php3?id_article=270 G Results of the pilot program on hydrogen-fuel cell buses The public service obligations proposal aims The EU Commission presented on 11 May at establishing a new legislative framework G New orientation for EU Transport the results of a pilot programme launched in for the increasingly open and competitive Policy 2003 that powered 27 hydrogen-fuel cell European market for public passenger The European Commission adopted on 22 public buses in 9 European cities. -

PORTUGAL 899 Send Them Send Them Can None Required for Most Visitors for for Most Visitors for None Required GMT/UTC

© Lonely Planet Publications 898 899 Portugal HIGHLIGHTS Óbidos This walled village was a royal wedding gift from Dom Dinis to his wife (beats a fondue set) and is overrun with tourists but still exquisite ( p917 ) Porto An intoxicating city, not just for its famous tipple but also for the vibrant street life and heady sights (p921 ) Best journey Bask in seagulls-and-seashore scenery from the Algarve train that runs beside the coast for most of the way between Lagos and Vila Real de Santo António ( p912 ) Off-the-beaten-track Parque Nacional da Peneda Gerês offers exceptional hiking through forests and over high plateaus dotted with ancient stone villages and archaeological sites( p924 ) FAST FACTS Area 92,389 sq km (twice the size of Switzerland as a comparison) ATMs plentiful Budget €40-50 Capital Lisbon Country code %351 Famous for fado, football, port, azulejos (tiles), salted cod Head of State President Anibal Cavaco Silva Language Portuguese Money euro (€); A$1 = €; CA$1 = €; ¥100 = €; NZ$1 = €; UK£1 = €; US $1 = € Time GMT/UTC. Daylight savings from Phrases bom dia (hello), obligado/a (thank March to October. you), desculpe (excuse me), adeus (good- Visas None required for most visitors for PORTUGAL bye), faz favor (please) stays up to 90 days Population 10.4 million TRAVEL HINTS Be wary of the nibbles provided at the start of a meal as they can cost and you can send them back. ROAMING PORTUGAL Check out Porto then Lisbon and nearby Sintra. Move on to Óbidos and coastal Nazaré before sidestepping to Évora and heading south to the Algarve. -

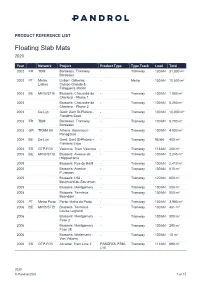

Floating Slab Mats 2020

PRODUCT REFERENCE LIST Floating Slab Mats 2020 Year Network Project Product Type Type Track Load Total 2002 FR TBM Bordeaux: Tramway - Tramway 100 kN 31,000 m² Bordeaux 2002 PT Metro Lisbon: Odivelas, - Metro 100 kN 10,000 m² Lisboa Campo Grande & Falagueira station 2003 BE MIVB/STIB Brussels: Chaussée de - Tramway 100 kN 1,800 m² Charleroi - Phase 1 2003 Brussels: Chaussée de - Tramway 100 kN 5,250 m² Charleroi - Phase 2 2003 De Lijn Gent: Gent St-Pieters - - Tramway 100 kN 10,000 m² Flanders Expo 2003 FR TBM Bordeaux: Tramway - Tramway 130 kN 9,700 m² Bordeaux 2003 GR TRAM SA Athens: Kasamouli - - Tramway 100 kN 4,000 m² Panagitsas 2004 BE De Lijn Gent: Gent St-Pieters - - Tramway 95 kN 400 m² Flanders Expo 2004 ES GTP-FGV Valencia: Tram Valencia - Tramway 113 kN 200 m² 2005 BE MIVB/STIB Brussels: Avenue de - Tramway 100 kN 2,245 m² l'Hippodrome 2005 Brussels: Rue du Bailli - Tramway 100 kN 2,410 m² 2005 Brussels: Avenue - Tramway 100 kN 610 m² P.Janson 2005 Brussels: L94 - - Tramway 120 kN 600 m² Boulevard du Souverain 2005 Brussels: Montgomery - Tramway 100 kN 250 m² 2005 Brussels: Terminus - Tramway 100 kN 550 m² Boondael 2005 PT Metro Porto Porto: Metro do Porto - Tramway 100 kN 3,900 m² 2006 BE MIVB/STIB Brussels: Terminus - Tramway 130 kN 481 m² Louise Legrand 2006 Brussels: Montgomery - Tramway 100 kN 300 m² Fase 2 2006 Brussels: Montgomery - Tramway 100 kN 290 m² Fase 2E 2006 Brussels: Wielemans - - Tramway 100 kN 15 m² Van Volxem 2006 ES GTP-FGV Alicante: Tram Line 2 PANDROL FSM- Tramway 113 kN 690 m² L10 2020 © Pandrol 2020 -

The Urban Rail Development Handbook

DEVELOPMENT THE “ The Urban Rail Development Handbook offers both planners and political decision makers a comprehensive view of one of the largest, if not the largest, investment a city can undertake: an urban rail system. The handbook properly recognizes that urban rail is only one part of a hierarchically integrated transport system, and it provides practical guidance on how urban rail projects can be implemented and operated RAIL URBAN THE URBAN RAIL in a multimodal way that maximizes benefits far beyond mobility. The handbook is a must-read for any person involved in the planning and decision making for an urban rail line.” —Arturo Ardila-Gómez, Global Lead, Urban Mobility and Lead Transport Economist, World Bank DEVELOPMENT “ The Urban Rail Development Handbook tackles the social and technical challenges of planning, designing, financing, procuring, constructing, and operating rail projects in urban areas. It is a great complement HANDBOOK to more technical publications on rail technology, infrastructure, and project delivery. This handbook provides practical advice for delivering urban megaprojects, taking account of their social, institutional, and economic context.” —Martha Lawrence, Lead, Railway Community of Practice and Senior Railway Specialist, World Bank HANDBOOK “ Among the many options a city can consider to improve access to opportunities and mobility, urban rail stands out by its potential impact, as well as its high cost. Getting it right is a complex and multifaceted challenge that this handbook addresses beautifully through an in-depth and practical sharing of hard lessons learned in planning, implementing, and operating such urban rail lines, while ensuring their transformational role for urban development.” —Gerald Ollivier, Lead, Transit-Oriented Development Community of Practice, World Bank “ Public transport, as the backbone of mobility in cities, supports more inclusive communities, economic development, higher standards of living and health, and active lifestyles of inhabitants, while improving air quality and liveability. -

Portugal Insight Paper

RURAL SHARED MOBILITY www.ruralsharedmobility.eu PORTUGAL INSIGHT PAPER Authors: Andrea Lorenzini, Giorgio Ambrosino MemEx Italy Photo by LEMUR on Unsplash Date: 15.02.2019 RURALITY (1) Degree of urbanisation for local administrative units Urban-rural typology for NUTS level 3 regions level 2 (LAU2) Cities Predominantly urban regions (rural population is less than 20% of the total population) Towns and suburbs Intermediate regions Rural Areas (rural population is between 20% and 50% of the total population) Data not available Predominantly rural regions (rural population is 50% or more of the total population) Source: Eurostat, JRCand European Commission Data not available Directorate-General for Regional Policy, May 2016 Source: Eurostat, JRC, EFGS, REGIO-GIS, December 2016 1 - Insight Paper - PORTUGAL RURAL SHARED MOBILITY DISTRIBUTION OF POPULATION Share of people living in Share of people living Share of people 43,6% 30.2% 26.3% cities in towns and suburbs living in rural areas Source: Eurostat, 2017 GEOGRAPHY Portugal is the most westerly country of the European and more facing the negative effects of these issues. In Union. Located mostly on the Iberian Peninsula in 2017, the share of people living in rural areas was 26.3% southwestern Europe, it borders to the north and (decreased of 1.4% in the latest 5 years) and 27.5% of east only with Spain, while to the north and south it the rural population was considered at risk of poverty borders the Atlantic Ocean with about 830 kilometres or social exclusion. Although the level of instruction -

UCLF21 Fan Leaflet

MESSAGE FROM UEFA MESSAGE FROM FPF Welcome to Porto! The UEFA Champions League final is an event I am delighted to welcome you to Porto, host city that is eagerly anticipated by football fans across of the 2021 UEFA Champions League Final. the world. Many of the game’s superstars capture the headlines in European football’s premier club Estádio do Dragão will host the third final of a competition, and they all want to brandish the Champions League in Portugal and the second in renowned trophy as a winner. a row, since just one year ago, UEFA chose Lisbon for a 'final eight' tournament. This season’s final is being staged in Porto, after we had to move the match from its original venue This decision honours the whole of Portuguese Istanbul at a late stage owing to the current football and the Portuguese Football Federation, circumstances. We were relieved to find a solution selected once again for its quick planning and so quickly that will enable supporters of the two expertise in delivering showpiece football events finalists, Manchester City FC and Chelsea FC, to and ensuring the safety of all those attending and see the match in person. Football fans have been participating in the game. through a difficult year, and UEFA felt that everything needed to be done to ensure that We should thank all the Portuguese authorities supporters of the two clubs could attend the final. and especially the Porto Municipality and FC Our thanks go to the Portuguese Football Porto for the support, availability and enthusiasm SUPPORTERS LEAFLET Federation (FPF) and the Portuguese government shown to host such a great event. -

What to Do with Your Free Time in Portugal

What To Do With Your Free Time in Portugal From bustling cities, full of lively culture and tasty treats, to hidden beaches and sprawling vineyards, Portugal has something for every traveler. Whether your idea of the perfect free time includes lounging on a beautiful beach, taking on a new adventure or strolling down narrow city-alleys, you are sure to find it all and more in Portugal. Destination Our Suggestion Important Info LAGOS Ponta da Piedade FREE – $ This beautiful coastal setting is accessible by boat or foot, just a few Hours: Dawn to dusk minutes south of Lagos’ center. By boat, you will arrive through natural Location: Accessible by boat caves and arches, while on foot your journey will take you along cliffs or foot from the center of and down a steep staircase to the beach. Take in your beautiful Lagos. surroundings and soak up some sun! Igreja de Santo Antonio FREE Church of Santo Antonio – Lagos was originally build in 1707 and Hours: 8:00 am – 7:00 pm; features incredible wood decorations on all walls. In addition to the open until 8:00 pm on beautiful walls and statues inside, look up to see the wooden, vaulted weekends ceiling and intricate prints it displays. Location: In the heart of Lagos, next to the Lagos Cultural Center. Lagos Marina FREE – $ Head here to kick-start any watersport adventure, or just to enjoy the Hours: Accessible 24/7! social atmosphere! The marina is not only the launchpad for many Location: Just across Ribeira water-based activities, but also home to countless bars and restaurants de Bensafrim from central where you can sit back and enjoy the view. -

The Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on the Tourism and Travel Sectors in Portugal

The impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the tourism and travel sectors in Portugal: Recommendations for maximising the contribution of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and the Cohesion Fund (CF) to the recovery Draft Final Report February 2021 This publication was produced for review by the Directorate-General Regional and Urban Policy (DG REGIO). It was prepared by Carlos Costa, Expert candidature number 2018-0451, under Contract No 2020CE16BAT068 1 Disclaimer The information and views set out in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report. Responsibility for accuracy of information contained in the report lies entirely with the author. 2 Table of contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. 18 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 19 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 22 1.1 Context and background information ......................................................................... 22 1.2 Context: The COVID-19 crisis and the tourism/travel crisis in Portugal ..................... 23 2. Overall approach and methodology ............................................................................ -

EBP-TBM Face Support Control in the Metro Do Porto Project

1 Proceedings 2005 Rapid Excavation & Tunneling Conference, Seattle EPB-TBM Face Support Control in the Metro do Porto Project, Portugal S. Babendererde, Babendererde Engineers LLC, Kent, WA; E. Hoek, Vancouver, BC, Canada; P.G. Marinos, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece; and A.S. Cardoso, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal Abstract The highly variable nature of the deeply weathered Oporto granite posed significant challenges in the driving of the 8.7km long Metro tunnels with 2 EPBTBMs. Early problems were encountered due to over excavation and face collapse in that extremely heterogeneous geology. Because of the last collapse with fatal consequences the project was interrupted. The difficulties were finally resolved by the introduction of an additional Active Face Support System which involves the injection of pressurized bentonite slurry to compensate automatically for deficiencies in the face support pressure. The project has now been completed with minimal surface subsidence and no face instability. 1. INTRODUCTION The planned integrated Metropolitan Transport System of Porto includes 70 km of track and 66 stations and excavation of the first section of the C and S lines started in August 2000. This first section, with 6.3 km tunnel and 11 stations, is located under the centre of the picturesque and densely populated city of Porto. The tunnel has an internal diameter of 7.8 m and accommodates two tracks. It was driven by two Earth Pressure Balanced (EPB) TBMs with outside diameters of 8.7 m and 8.9 m. The alignment has a maximum cover of 32 m and a minimum of 3 m. -

Contracting in Urban Public Transport Appendix: Contract Tables

Contracting in urban public transport Appendix: Contract Tables Submitted to EC – DG TREN by inno-V | KCW | RebelGroup | NEA | TØI | SDG | TIS Contracting in urban public transport (appendix: contract tables) Contracted by: European Commission – DG TREN Contractors: NEA (NL), inno-V (NL), KCW (D), Re- belGroup (NL), TØI (N), SDG (GB), TIS.PT (P) Project co-ordinator: inno-V (NL) Main report written by: Didier van de Velde, Arne Beck, Jan- Coen van Elburg, Kai-Henning Ter- schüren With further contributions of: Bård Norheim, Jan Werner, Christoph Schaaffkamp, Arthur Gleijm Contract tables provided by: Didier van de Velde, Arne Beck, Bård Norheim, Frode Longva, Tamás Dombi, Nicole Rudolf, Andrew Mellor, Daniela Carvalho, Rosário Macário, Kai-Henning Terschüren Layout: Didier van de Velde, Annemone Meyer, Arne Beck Disclaimer: This report was produced for DG En- ergy and Transport and represents the Consultants views. These views have not been adopted or in any way ap- proved by the Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission's or DG Energy and Transport's views, nor of the confor- mity of described practices with appli- cable Community law. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. File: contracting in urban public transport - contract tables (v4.2) pub.doc Date: Amsterdam, 14 January 2008 Contracting in urban public transport (appendix: contract tables) 2 Table of contents 1 TEMPLATE...........................................................................................................4 2 AMSTERDAM (NL): DIRECT AWARD WITH COMPETITIVE THREAT ..........................6 3 BARCELONA (E): DIRECT AWARD TO PUBLIC OPERATOR........................................9 4 BRUSSELS (B): DIRECT AWARD TO PUBLIC OPERATOR ..........................................11 5 BUDAPEST (H): DIRECT AWARD TO PUBLIC OPERATOR....................................... -

Social and Spatial Continuities and Differentiations Among Portuguese Ciganos: Regional Profiles

STUDIA UBB SOCIOLOGIA, 61 (LXI), 1, 2016, pp. 5-36 DOI: 10.1515/subbs-2016-0001 SOCIAL AND SPATIAL CONTINUITIES AND DIFFERENTIATIONS AMONG PORTUGUESE CIGANOS: REGIONAL PROFILES MARIA MANUELA MENDES,1 OLGA MAGANO2 AND PEDRO CANDEIAS3 Abstract. The coexistence of people and societies marked by ethnic, social, cultural, religious and linguistic diversity is a subject that still generates controversies in contemporary societies. The “Ciganos’ situation” is an unavoidable issue that crosses the boundaries of different European countries, which leads to controversy and ambivalence in the so-called multicultural and/or intercultural societies characterised by the principle of universalism. In Portugal, despite the social and economic transformations that have occurred, the problems of exclusion and poverty among Ciganos persist. They are still considered the poorest ethnic group, with the worst housing conditions, lest schooling and the main target of racism and discrimination. The Portuguese Ciganos are not a homogeneous community. The diversity and plurality are not always easy to grasp by the glare generated by the adoption of interpretive perspectives that are reductively linear and deterministic of the Portuguese Ciganos. For the purpose of outlining a national picture of Portuguese Ciganos, a national study was developed that combines both qualitative and quantitative methodological approaches. The central goal of this article is to present the main results obtained through a questionnaire survey carried out to Ciganos persons and to discuss