Transnationalism and Genealogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Immigrant Parenting in the United States and Singapore

genealogy Article Challenges and Strategies for Promoting Children’s Education: A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Immigrant Parenting in the United States and Singapore Min Zhou 1,* and Jun Wang 2 1 Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551, USA 2 School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639818, Singapore; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 February 2019; Accepted: 11 April 2019; Published: 15 April 2019 Abstract: Confucian heritage culture holds that a good education is the path to upward social mobility as well as the road to realizing an individual’s fullest potential in life. In both China and Chinese diasporic communities around the world, education is of utmost importance and is central to childrearing in the family. In this paper, we address one of the most serious resettlement issues that new Chinese immigrants face—children’s education. We examine how receiving contexts matter for parenting, what immigrant parents do to promote their children’s education, and what enables parenting strategies to yield expected outcomes. Our analysis is based mainly on data collected from face-to-face interviews and participant observations in Chinese immigrant communities in Los Angeles and New York in the United States and in Singapore. We find that, despite different contexts of reception, new Chinese immigrant parents hold similar views and expectations on children’s education, are equally concerned about achievement outcomes, and tend to adopt overbearing parenting strategies. We also find that, while the Chinese way of parenting is severely contested in the processes of migration and adaptation, the success in promoting children’s educational excellence involves not only the right set of culturally specific strategies but also tangible support from host-society institutions and familial and ethnic social networks. -

University of Cape Town

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Lost Soldiers from Lost Wars: A Comparative Study of the Collective Experience of Soldiers of the Vietnam War and the Angoran/Namibian Border War by Gretchen Bourland Rudham BRLGRE002 Town Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts inCape English (American Studies) of Department of English Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town University2003 This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people, has,.,bee!l pttributed, and has been cited and referenced. Jr~ 3. ~c.Y~ignature Lost Soldiers from Lost Wars: A Comparative Study of the Collective Experience of Soldiers of the Vietnam War and the Angolan/Namibian Border War I explore the Vietnam War and the Border War of South Africa through the analysis of the oral histories of the soldiers who fought in these wars. Considering the scarcity of oral histories about the Border War, I conducted several personal interviews with Border War soldiers to add to the oral histories representing that conflict. -

The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan Independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Dalei Jie University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Jie, Dalei, "The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010)" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 524. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/524 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise and Fall of the Taiwan independence Policy: Power Shift, Domestic Constraints, and Sovereignty Assertiveness (1988-2010) Abstract How to explain the rise and fall of the Taiwan independence policy? As the Taiwan Strait is still the only conceivable scenario where a major power war can break out and Taiwan's words and deeds can significantly affect the prospect of a cross-strait military conflict, ot answer this question is not just a scholarly inquiry. I define the aiwanT independence policy as internal political moves by the Taiwanese government to establish Taiwan as a separate and sovereign political entity on the world stage. Although two existing prevailing explanations--electoral politics and shifting identity--have some merits, they are inadequate to explain policy change over the past twenty years. Instead, I argue that there is strategic rationale for Taiwan to assert a separate sovereignty. Sovereignty assertions are attempts to substitute normative power--the international consensus on the sanctity of sovereignty--for a shortfall in military- economic-diplomatic assets. -

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

Contact Languages: Ecology and Evolution in Asia

This page intentionally left blank Contact Languages Why do groups of speakers in certain times and places come up with new varieties of languages? What are the social settings that determine whether a mixed language, a pidgin, or a Creole will develop, and how can we under- stand the ways in which different languages contribute to the new grammar? Through the study of Malay contact varieties such as Baba and Bazaar Malay, Cocos Malay, and Sri Lanka Malay, as well as the Asian Portuguese ver- nacular of Macau, and China Coast Pidgin, the book explores the social and structural dynamics that underlie the fascinating phenomenon of the creation of new, or restructured, grammars. It emphasizes the importance and inter- play of historical documentation, socio-cultural observation, and linguistic analysis in the study of contact languages, offering an evolutionary frame- work for the study of contact language formation – including pidgins and Creoles – in which historical, socio-cultural, and typological observations come together. umberto ansaldo is Associate Professor in Linguistics at the University of Hong Kong. He was formerly a senior researcher and lecturer with the Amsterdam Center for Language and Communication at the University of Amsterdam. He has also worked in Sweden and Singapore and conducted fieldwork in China, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Christmas Island, and Sri Lanka. He is the co-editor of the Creole Language Library Series and has co-edited various journals and books including Deconstructing Creole (2007). Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact General Editor Salikoko S. Mufwene, University of Chicago Editorial Board Robert Chaudenson, Université d’Aix-en-Provence Braj Kachru, University of Illinois at Urbana Raj Mesthrie, University of Cape Town Lesley Milroy, University of Michigan Shana Poplack, University of Ottawa Michael Silverstein, University of Chicago Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact is an interdisciplinary series bringing together work on language contact from a diverse range of research areas. -

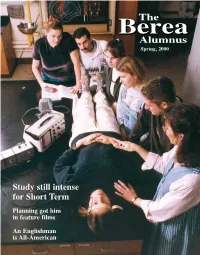

Study Still Intense for Short Term Planning Got Him in Feature Films

Spring, 2000 Study still intense for Short Term Planning got him in feature films An Englishman is All-American Editor’s Notes . Rod Bussey, ’63, Publisher Ed Ford, Fd ’54, Cx’58, Interim Editor Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Managing Editor Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Class Notes Editor The Berea Alumnus is published quarterly for Berea College alumni and friends by the Berea College Public Relations Department, CPO 2216, Berea, Ky. 40404. Periodical Postage paid at Berea, Ky. and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address corrections to Fukushima Keido (right), head of the Tofuku Temple in Kyoto, Japan, prepares a Japanese ink THE BEREA ALUMNUS, c/o Berea College painting banner at the recent Japan Semester Focus 2000 program sponsored by the Alumni Association, CPO 2203, Berea, Ky. International Center. 40404. Phone (859) 985-3104. ALUMNI ASSOCIATION STAFF Bringing the world to Berea—one of the major goals of the College’s Rod Bussey, ’63, Vice President for Alumni International Center—became a reality with the beginning of the Spring Term. Relations and Development Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Executive Japanese arts, culture and history are included in an in-depth program that Director of Alumni Relations began in January and continues through May. Some of the highlights concerning Mary Labus, ’78, Associate Director the focus on Japan and its impact on the campus community are in Julie Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Associate Director Melanie Conley Turner, ’94, Office Manager Sowell’s story that begins on page 8. Norma Proctor Kennedy, ’80, Secretary Motion picture actors have explored a variety of avenues in their quests to ALUMNI EXECUTIVE COUNCIL build film careers. -

Rice Bowl Cafe Excellent Chinese Dining & Sushi at the Rice Bowl Cafe, We Want You to Have the Most Enjoyable Experience Possible

Rice Bowl Cafe Excellent Chinese Dining & Sushi At the Rice Bowl Cafe, we want you to have the most enjoyable experience possible. We use only the highest quality ingredients and prepare all your food fresh when you order and never use MSG. While you are here, try our soothing and refreshing herbal tea. The healthy benefits and great taste make our tea an excellent compliment to your meal. Our freshly made Edamame or mix & match Nigiri sushi can be fun appetizers. Before completing your meal, leave some room for a delicious dessert from our new dessert menu. Thank you for your visit! All menu items & prices subject to change. Chinese Herbal Chrysanthemum Tea APPETIZERS Pork or Vegetable Egg Roll 1.09 Hand-made cabbage roll with your choice of pork or vegetables Shrimp Spring Roll (2) 3.29 Lettuce, carrot, cucumber, and shrimp in rice paper with peanut & sweet chili sauce Cream Cheese Wonton (6) 3.99 Fresh, crispy wontons filled with cream cheese Sugar Biscuits (10) 3.99 Warm and crispy fried biscuits coated in sugar Edamame 3.99 Steamed sugar snap peas lightly dusted in sea salt Chicken (4) or Beef (3) Teriyaki 4.29 Chicken or Beef strips with a tasty teriyaki sauce Pan Fried or Steamed Dumplings (8) 4.99 Eight (8) hand-made dumplings, fried or steamed to perfection Garlic Chicken Wings (6) 4.99 Chicken wings, fried and coated with garlic seasoning Shrimp Tempura 6.99 Light and crispy hand-dipped tempura coating on shrimp Rice Bowl Sampler 5.99 Two (2) pork egg rolls, four (4) cream cheese wontons, and two (2) chicken teriyaki strips Shrimp -

Language Ideologies, Chinese Identities and Imagined Futures Perspectives from Ethnic Chinese Singaporean University Students

Journal of Chinese Overseas 17 (2021) 1–30 brill.com/jco Language Ideologies, Chinese Identities and Imagined Futures Perspectives from Ethnic Chinese Singaporean University Students 语言意识形态、华人身份认同、未来憧憬: 新加坡华族大学生的视野 Audrey Lin Lin Toh1 (陶琳琳) | ORCID: 0000-0002-2462-7321 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore [email protected] Hong Liu2 (刘宏) | ORCID: 0000-0003-3328-8429 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore [email protected] Abstract Since independence in 1965, the Singapore government has established a strongly mandated education policy with an English-first and official mother tongue Mandarin-second bilingualism. A majority of local-born Chinese have inclined toward a Western rather than Chinese identity, with some scholars regarding English as Singapore’s “new mother tongue.” Other research has found a more local identity built on Singlish, a localized form of English which adopts expressions from the ethnic mother tongues. However, a re-emergent China and new waves of mainland migrants over the past two decades seem to have strengthened Chinese language ideologies in the nation’s linguistic space. This article revisits the intriguing relationships between language and identity through a case study of Chineseness among young ethnic Chinese Singaporeans. Guided by a theory of identity and investment and founded on 1 Lecturer, Language and Communication Centre, School of Humanities, Nanyang Techno- logical University, Singapore. 2 Tan Lark Sye Chair Professor in Public Policy and Global Affairs, School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. © Audrey Lin Lin Toh and Hong Liu, 2021 | doi:10.1163/17932548-12341432 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY 4.0Downloaded license. -

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy

China, Cambodia, and the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence: Principles and Foreign Policy Sophie Diamant Richardson Old Chatham, New York Bachelor of Arts, Oberlin College, 1992 Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2001 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia May, 2005 !, 11 !K::;=::: .' P I / j ;/"'" G 2 © Copyright by Sophie Diamant Richardson All Rights Reserved May 2005 3 ABSTRACT Most international relations scholarship concentrates exclusively on cooperation or aggression and dismisses non-conforming behavior as anomalous. Consequently, Chinese foreign policy towards small states is deemed either irrelevant or deviant. Yet an inquiry into the full range of choices available to policymakers shows that a particular set of beliefs – the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence – determined options, thus demonstrating the validity of an alternative rationality that standard approaches cannot apprehend. In theoretical terms, a belief-based explanation suggests that international relations and individual states’ foreign policies are not necessarily determined by a uniformly offensive or defensive posture, and that states can pursue more peaceful security strategies than an “anarchic” system has previously allowed. “Security” is not the one-dimensional, militarized state of being most international relations theory implies. Rather, it is a highly subjective, experience-based construct, such that those with different experiences will pursue different means of trying to create their own security. By examining one detailed longitudinal case, which draws on extensive archival research in China, and three shorter cases, it is shown that Chinese foreign policy makers rarely pursued options outside the Five Principles. -

The Chinese in Cambodia. William E

CHINESE CAMBODIAN FROM WIKIPEDIA, THE FREE ENCYCLOPEDIA "The Khmer Rouge reduced the numbers of the sino-cambodian from 430,000 in 1975 to 215,000 in 1979" Chinese Cambodians are Cambodian citizens of Chinese descent. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, they were the largest ethnic group in Cambodia; there were an estimated 425,000. However, by 1984, there were only 61,400 Chinese Cambodians left. This has been attributed to a combination of warfare, Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese persecution, and emigration. In 1963, William Willmott, an expert on overseas Chinese communities, estimated that 90% of the Chinese in Cambodia were involved in commerce. Today, an estimated 60% are urban dwellers engaged mainly in commerce, with most of the rural population working as shopkeepers, processors of food products (such as rice, palm sugar, fruit, and fish), and moneylenders. Those in Kampot Province and parts of Kaoh Kong Province cultivate black pepper and fruit (especially rambutans, durians, and coconuts). Additionally, some rural Chinese Cambodians are engaged in salt water fishing. Most Chinese Cambodian moneylenders wield considerable economic power over the ethnic Khmer peasants through usury. Studies in the 1950s revealed that Chinese shopkeepers in Cambodia would sell to peasants on credit at interest rates of 10-20% a month. This might have been the reason why seventy-five percent of the peasants in Cambodia were in debt in 1952, according to the Australian Colonial Credit Office. There seemed to be little distinction between Chinese and Sino-Khmer (offspring of mixed Chinese and Khmer descent) in the moneylending and shopkeeping enterprises. -

Side Orders Fried Rice Noodles/Lo Mein Beef Wings Egg Foo Young

Side Orders Wings Chicken (Served With Fried Rice) 48. SWEET AND SOUR CHICKEN ............................................................................................. 8.95 1. EGG ROLLS (2) .............................. 1.95 49. MOO GOO GAI PAN ......................................................................................................... 8.95 2. CREAM CHEESE PUFFS (10) .......... 4.95 26. GARLIC WINGS (5) .......................... 6.10 50. PEPPER CHICKEN AND ONION ......................................................................................... 8.95 3. FRIED FILLET FISH + FRIES ............ 7.50 27. SPICY WINGS (5) ............................ 6.10 51. CHICKEN WITH BROCCOLI ................................................................................................ 8.95 4. POPCORN SHRIMP + FRIES .......... 7.50 28. CURRY WINGS (5) .......................... 6.10 52. KUNG PAO CHICKEN ........................................................................................................ 8.95 5. FRENCH FRIES .............................. 2.25 29. TERIYAKI WINGS (5) ....................... 6.10 53. CURRY CHICKEN ............................................................................................................... 8.95 6. FRIED CHICKEN WINGS (6) ........... 5.95 30. HONEY WINGS (5) .......................... 6.10 54. CHICKEN IN GARLIC SAUCE .............................................................................................. 8.95 31. LEMON PEPPER WINGS (5) ............ 6.10 55. CASHEW CHICKEN -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants.