The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Browsing Through Bias: the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies

Browsing through Bias: The Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings for African American Studies and LGBTQIA Studies Sara A. Howard and Steven A. Knowlton Abstract The knowledge organization system prepared by the Library of Con- gress (LC) and widely used in academic libraries has some disadvan- tages for researchers in the fields of African American studies and LGBTQIA studies. The interdisciplinary nature of those fields means that browsing in stacks or shelflists organized by LC Classification requires looking in numerous locations. As well, persistent bias in the language used for subject headings, as well as the hierarchy of clas- sification for books in these fields, continues to “other” the peoples and topics that populate these titles. This paper offers tools to help researchers have a holistic view of applicable titles across library shelves and hopes to become part of a larger conversation regarding social responsibility and diversity in the library community.1 Introduction The neat division of knowledge into tidy silos of scholarly disciplines, each with its own section of a knowledge organization system (KOS), has long characterized the efforts of libraries to arrange their collections of books. The KOS most commonly used in American academic libraries is the Li- brary of Congress Classification (LCC). LCC, developed between 1899 and 1903 by James C. M. Hanson and Charles Martel, is based on the work of Charles Ammi Cutter. Cutter devised his “Expansive Classification” to em- body the universe of human knowledge within twenty-seven classes, while Hanson and Martel eventually settled on twenty (Chan 1999, 6–12). Those classes tend to mirror the names of academic departments then prevail- ing in colleges and universities (e.g., Philosophy, History, Medicine, and Agriculture). -

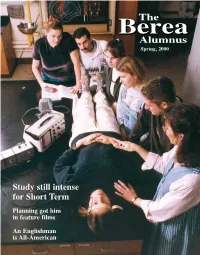

Study Still Intense for Short Term Planning Got Him in Feature Films

Spring, 2000 Study still intense for Short Term Planning got him in feature films An Englishman is All-American Editor’s Notes . Rod Bussey, ’63, Publisher Ed Ford, Fd ’54, Cx’58, Interim Editor Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Managing Editor Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Class Notes Editor The Berea Alumnus is published quarterly for Berea College alumni and friends by the Berea College Public Relations Department, CPO 2216, Berea, Ky. 40404. Periodical Postage paid at Berea, Ky. and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address corrections to Fukushima Keido (right), head of the Tofuku Temple in Kyoto, Japan, prepares a Japanese ink THE BEREA ALUMNUS, c/o Berea College painting banner at the recent Japan Semester Focus 2000 program sponsored by the Alumni Association, CPO 2203, Berea, Ky. International Center. 40404. Phone (859) 985-3104. ALUMNI ASSOCIATION STAFF Bringing the world to Berea—one of the major goals of the College’s Rod Bussey, ’63, Vice President for Alumni International Center—became a reality with the beginning of the Spring Term. Relations and Development Jackie Collier Ballinger, ’80, Executive Japanese arts, culture and history are included in an in-depth program that Director of Alumni Relations began in January and continues through May. Some of the highlights concerning Mary Labus, ’78, Associate Director the focus on Japan and its impact on the campus community are in Julie Shelley Boone Rhodus, ’85, Associate Director Melanie Conley Turner, ’94, Office Manager Sowell’s story that begins on page 8. Norma Proctor Kennedy, ’80, Secretary Motion picture actors have explored a variety of avenues in their quests to ALUMNI EXECUTIVE COUNCIL build film careers. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABRAMS Abrams, Douglas Carlton. The lost diary of Don Juan FIC/ADDIEGO Addiego, John. The islands of divine music FIC/ADLER Adler, H. G. The journey : a novel FIC/AGEE Agee, James, 1909-1955. A death in the family [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Briar Bank : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALCOTT Alcott, Louisa May The inheritance FIC/ALLBEURY Allbeury, Ted. Deadly departures FIC/AMBLER Ambler, Eric, 1909-1998. A coffin for Dimitrios FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth [MYST] FIC/ARRUDA Arruda, Suzanne Middendorf The leopard's prey : a Jade del Cameron mystery [MYST] FIC/ASHFORD Ashford, Jeffrey, 1926- A dangerous friendship [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity slays the dragon FIC/ATKINS Atkins, Charles. Ashes, ashes [MYST] FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. When will there be good news? : a novel FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Emma FIC/BAGGOTT Baggott, Julianna. Girl talk [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A slaying in Savannah : a Murder, she wrote mystery, a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A vote for murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- Margaritas & murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel FIC/BAKER Baker, Kage. -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001). -

China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a Strategic Economic and Trade Relationship

China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a strategic economic and trade relationship Osvaldo Rosales Mikio Kuwayama UNITED NATIONS China and Latin America and the Caribbean Building a strategic economic and trade relationship Osvaldo Rosales Mikio Kuwayama E C L n c Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Santiago, April 2012 Libros de la CEPAL Alicia Bárcena Executive Secretary Antonio Prado Deputy Executive Secretary Osvaldo Rosales Chief of the Division of International Trade and Integration Ricardo Pérez Chief of the Documents and Publications Division This document was prepared by Osvaldo Rosales and Mikio Kuwayama, Chief and Economic Affairs Officer, respectively, of the Division of International Trade and Integration of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Statistical support was provided by José Durán Lima and Mariano Alvarez, of the same Division. The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Organization. Cover design: José Manuel Vélez United Nations publication ISBN: 978-92-1-021082-9 • E-ISBN: 978-92-1-055362-9 LC/G.2519-P Sales No. E.12.II.G.12 Copyright © United Nations, April 2012. All rights reserved Printed at United Nations, Santiago, Chile • 2011-914 Applications for the right to reproduce this work are welcomed and should be sent to the Secretary of the Publications Board, United Nations Headquarters, New York, N.Y. 10017, United States. Member States and the governmental institutions may reproduce this work without prior authorization, but are requested to mention the source and inform the United Nations of such reproduction. -

Cemetery Dance: an Agent Pendergast Novel Free

FREE CEMETERY DANCE: AN AGENT PENDERGAST NOVEL PDF Douglas Preston,Lincoln Child | 512 pages | 25 Mar 2010 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780752884189 | English | London, United Kingdom Cemetery Dance (novel) - Wikipedia Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. For a better shopping experience, please upgrade now. Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Enabling JavaScript in your browser will allow you to experience all the features of our site. Learn how to enable JavaScript on your browser. NOOK Book. Preston and Child's Relic and The Cabinet of Curiosities were chosen by readers in a National Public Radio poll as Cemetery Dance: An Agent Pendergast Novel among the one hundred greatest Cemetery Dance: An Agent Pendergast Novel ever written, and Relic was made into a number-one box office hit movie. Preston's acclaimed nonfiction book, The Monster of Florenceis being made into a movie starring George Clooney. Lincoln Child is a former book editor who has published five novels of his own, including the huge bestseller Deep Storm. Readers Cemetery Dance: An Agent Pendergast Novel sign up for The Pendergast File, a monthly "strangely entertaining note" from the authors, at their website, www. The authors welcome visitors to their alarmingly active Facebook page, where they post regularly. Place of Birth:. Home 1 Books 2. Add to Wishlist. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Members save with free shipping everyday! See details. Their serpentine journey takes them to an enclave of Manhattan they never imagined could exist: a secretive, reclusive cult of Obeah and vodou which no outsiders have ever survived. -

Tapemaster Main Copy

Jeff Schechtman Interviews December 1995 to January 2018 2018 Daniel Pink When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing 1/18/18 Martin Shiel WhoWhatWhy Story on Deutsche Bank 1/17/18 Sara Zaske Achtung Baby: An American Mom on the German Art of Raising Self-Reliant Children 1/17/18 Frances Moore Lappe Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning and Connection for the America We Want 1/16/18 Martin Puchner The Written Word: The Power of Stories to Shape People, History, Civilization 1/11/18 Sarah Kendzior Author /Journalist “The View From Flyover Country” 1/11/18 Gordon Whitman Stand Up! How to Get Involved, Speak Out and Win in a World on Fire 1/10/18 Brian Dear The Friendly Orange Glow: The Untold Story of the PLATO System and the Dawn of Cyberculture 1/9/18 Valter Longo The Longevity Diet: The New Science behind Stem Cell Activation 1/9/18 Richard Haass The World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order 1/8/18 Chloe Benjamin The Immortalists: A Novel 1/5/18 2017 Morgan Simon Real Impact: The New Economics of Social Change 12/20/17 Daniel Ellsberg The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a War Planner 12/19/17 Tom Kochan Shaping the Future of Work: A Handbook for Action and a New Social Contract 12/15/17 David Patrikarakos War in 140 Characters: How Social Media is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty First Century 12/14/17 Gary Taubes The Case Against Sugar 12/13/17 Luke Harding Collusion: Secret Meetins, Dirty Money and How Russia Helped Donald Trump Win 12/13/17 Jake Bernstein Secrecy World: Inside the Panama Papers -

American Blockbuster Movies, Technology, and Wonder

MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, AND WONDER MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, charles r. acland AMERICAN BLOCKBUSTER SIGN, STORAGE, TRANSMISSION A series edited by Jonathan Sterne and Lisa Gitelman AMERICAN BLOCKBUSTER MOVIES, TECHNOLOGY, AND WONDER charles r. acland duke university press · Durham and London · 2020 © 2020 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Whitman and Helvetica lt Standard by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Acland, Charles R., [date] author. Title: American blockbuster : movies, technology, and wonder / Charles R. Acland. Other titles: Sign, storage, transmission. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Series: Sign, storage, transmission | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2019054728 (print) lccn 2019054729 (ebook) isbn 9781478008576 (hardcover) isbn 9781478009504 (paperback) isbn 9781478012160 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Cameron, James, 1954– | Blockbusters (Motion pictures)— United States—History and criticism. | Motion picture industry—United States— History—20th century. | Mass media and culture—United States. Classification:lcc pn1995.9.b598 a25 2020 (print) | lcc pn1995.9.b598 (ebook) | ddc 384/.80973—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054728 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019054729 Cover art: Photo by Rattanachai Singtrangarn / Alamy Stock Photo. FOR AVA, STELLA, AND HAIDEE A technological rationale is the rationale of domination itself. It is the coercive nature of society alienated from itself. Automobiles, bombs, and movies keep the whole thing together. — MAX HORKHEIMER AND THEODOR ADORNO, Dialectic of Enlightenment, 1944/1947 The bud get is the aesthetic. — JAMES SCHAMUS, 1991 (contents) Acknowl edgments ........................................................... -

Faulty Math: the Economics of Legalizing the Grey Album

File: BambauerMerged2 Created on: 1/31/2008 4:34 PM Last Printed: 2/13/2008 3:38 PM FAULTY MATH: THE ECONOMICS OF LEGALIZING THE GREY ALBUM Derek E. Bambauer* ABSTRACT ................................................................................................. 346 I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 346 II. MISSED OPPORTUNITIES ..................................................................... 348 III. COPYRIGHT’S UNUSUAL ECONOMICS................................................. 354 IV. ECONOMIC THEORIES SUPPORTING THE DERIVATIVE WORKS RIGHT 357 A. Reducing Transaction Costs........................................................... 358 1. Theory: Copyright as Clearinghouse ....................................... 358 2. Analysis: Second-Best at Cutting Costs.................................... 359 B. Enabling Price Discrimination....................................................... 361 1. Theory: Broadening Access, Boosting Returns ........................ 361 2. Analysis: Movie Rentals and Other Weaknesses...................... 364 a. Access................................................................................. 364 b. Production.......................................................................... 367 c. Shortcomings...................................................................... 368 C. Exploiting Markets Efficiently........................................................ 368 1. Theory: Digging Dry Wells ..................................................... -

Adult Fiction Audiobooks on Cd | Updated April 2015

CASE MEMORIAL LIBRARY | ADULT FICTION AUDIOBOOKS ON CD | UPDATED APRIL 2015 AUTHOR TITLE Adams, Richard, 1920- Watership Down [sound recording] / Richard Adams. Adiga, Aravind. The white tiger [sound recording] / by Aravind Adiga. Adler, Elizabeth (Elizabeth A.) The house in Amalfi [sound recording] / by Elizabeth Adler. Albom, Mitch, author The first phone call from heaven [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Albom, Mitch, 1958- For one more day [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven [sound recording] / Mitch Albom. Alcott, Kate, author. The daring ladies of Lowell [sound recording] / Kate Alcott. Allende, Isabel. Maya's notebook [sound recording] / Isabel Allende. Anderson, Kevin J., 1962- The last days of Krypton [sound recording] / Kevin J. Anderson. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Ladies' night [sound recording] : [a novel] / Mary Kay Andrews. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- Savannah breeze [sound recording] / by Mary Kay Andrews. Andrews, Mary Kay, 1954- author. Christmas bliss [sound recording] / Mary Kay Andrews. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Best kept secret [sound recording] : a novel / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- False impression [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Only time will tell [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- Paths of glory [sound recording] : a novel / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- author. Be careful what you wish for [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Archer, Jeffrey, author. Mightier than the sword [sound recording] / Jeffrey Archer. Asimov, Isaac, 1920-1992. The caves of steel [sound recording] / Isaac Asimov. Asimov, Isaac, 1920-1992. The Robots of Dawn [sound recording] / Isaac Asimov. Atkinson, Kate. -

Books Sandwiched in SPRING Programs 2019

Rochester Reads 2019 Presented by American War by Omar El Akkad Reading and Book Signing by the Author rd Wednesday, March 27 33 Annual Sokol 12 noon – 1:30pm High School Literary Awards Kate Gleason Auditorium SPRING Offered in partnership with Writers & Books. Reception and Ceremony Omar El Akkad was born in Cairo, Egypt and grew up in Thursday, May 2 • 4pm Programs 2019 Kate Gleason Auditorium, Central Library Doha, Qatar until he moved to Canada with his family. He is an award-winning journalist and author who has traveled around the world to cover many of the most Hear winning poetry, prose and featuring important news stories of the last decade. His reporting performance entries from Monroe County includes dispatches from the NATO-led war in Afghanistan, students in grades 9 – 12. ndw the military trials at Guantànamo Bay, the Arab Spring Sa iche revolution in Egypt and the Black Lives Matter movement ks d Monroe County students in grades 9 – 12 may o in Ferguson, Missouri. He lives in Portland, Oregon. o In His debut novel, American War, was published to critical enter original poetry and/or prose, either written B acclaim in the Spring of 2017. or performed, to be judged by nationally-known authors for cash prizes. Friends & Foundation of the Visit www.Sokol.ffrpl.org for more information. Rochester Public Library Your donations in 2019 help us to present programs, support special projects, create specialized spaces, The Friends & Foundation of the Rochester and purchase supplemental materials & equipment Public Library has a 65-year history of serving for the Rochester Public Library. -

American War

DISCUSSION GUIDE: AMERICAN WAR The introduction, author biography, discussion questions, and suggested reading that follow are designed to enhance your group’s discussion of American War, the powerful debut novel by Omar El Akkad. CATEGORIES: Comparative Literature | Dystopian Literature Comparative Literature | Literature of Peace and War Comparative Literature | Science Fiction First-Year Experience | Common Reading Vintage | Paper | 978-1-101-97313-4 | 432 pages | $16.95 Also available in hardcover, ebook, and audiobook INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK AMERICAN WAR tells the story of a second American Civil War, a devastating plague, and one family caught deep in the middle. Its pages explore what might happen if America were to turn its most devastating policies and deadly weapons upon itself. Sarat Chestnut, born in Louisiana, is only six when the Second American Civil War breaks out in 2074. But even she knows that oil is outlawed, that Louisiana is half underwater, and that unmanned drones fill the sky. When her father is killed and her family is forced into Camp Patience for displaced persons, she begins to grow up shaped by her particular time and place. But not everyone at Camp Patience is who they claim to be. Eventually Sarat is befriended by a mysterious functionary, under whose influence she is turned into a deadly instrument of war. The decisions that she makes will have tremendous consequences not just for Sarat but for her family and her country, rippling through generations of strangers and kin alike. SHORTLIST | 2018 | James Tait Black Memorial Prize PHOTO © MICHAEL LIONSTAR ABOUT THE AUTHOR OMAR EL AKKAD was born in Cairo, Egypt and grew up in Doha, Qatar until he moved to Canada with his family.