Milhaud a MESSAGE from the MILKEN ARCHIVE FOUNDER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Music

Prairie View A&M University HenryMusic Library 5/18/2011 KEYBOARD CD 21 The Women’s Philharmonic Angela Cheng, piano Gillian Benet, harp Jo Ann Falletta, conductor Ouverture (Fanny Mendelssohn) Piano Concerto in a minor, Op. 7 (Clara Schumann) Concertino for Harp and Orchestra (Germaine Tailleferre) D’un Soir Triste (Lili Boulanger) D’un Matin de Printemps (Boulanger) CD 23 Pictures for Piano and Percussion Duo Vivace Sonate für Marimba and Klavier (Peter Tanner) Sonatine für drei Pauken und Klavier (Alexander Tscherepnin) Duettino für Vibraphon und Klavier, Op. 82b (Berthold Hummel) The Flea Market—Twelve Little Musical Pictures for Percussion and Piano (Yvonne Desportes) Cross Corners (George Hamilton Green) The Whistler (Green) CD 25 Kaleidoscope—Music by African-American Women Helen Walker-Hill, piano Gregory Walker, violin Sonata (Irene Britton Smith) Three Pieces for Violin and Piano (Dorothy Rudd Moore) Prelude for Piano (Julia Perry) Spring Intermezzo (from Four Seasonal Sketches) (Betty Jackson King) Troubled Water (Margaret Bonds) Pulsations (Lettie Beckon Alston) Before I’d Be a Slave (Undine Smith Moore) Five Interludes (Rachel Eubanks) I. Moderato V. Larghetto Portraits in jazz (Valerie Capers) XII. Cool-Trane VII. Billie’s Song A Summer Day (Lena Johnson McLIn) Etude No. 2 (Regina Harris Baiocchi) Blues Dialogues (Dolores White) Negro Dance, Op. 25 No. 1 (Nora Douglas Holt) Fantasie Negre (Florence Price) CD 29 Riches and Rags Nancy Fierro, piano II Sonata for the Piano (Grazyna Bacewicz) Nocturne in B flat Major (Maria Agata Szymanowska) Nocturne in A flat Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 19 in C Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. 8 in D Major (Szymanowska) Mazurka No. -

03 May 2021.Pdf

3 May 2021 12:01 AM Francesco Geminiani (1687-1762) Concerto grosso in D minor, Op 7 No 2 La Petite Bande, Sigiswald Kuijken (conductor) DEWDR 12:10 AM Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959) Prelude for guitar no.1 in E minor Norbert Kraft (guitar) CACBC 12:15 AM Sergey Rachmaninov (1873-1943) 2 Songs: When Night Descends in silence; Oh stop thy singing maiden fair Fredrik Zetterstrom (baritone), Tobias Ringborg (violin), Anders Kilstrom (piano) SESR 12:24 AM Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) Serenade no 2 in G minor for violin & orchestra, Op 69b Judy Kang (violin), Orchestre Symphonique de Laval CACBC 12:33 AM Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Polonaise No.2 in E major from (S.223) Ferruccio Busoni (piano) SESR 12:43 AM Giovanni Gabrieli (1557-1612) Exaudi me, for 12 part triple chorus, continuo and 4 trombones Danish National Radio Chorus, Copenhagen Cornetts & Sackbutts, Lars Baunkilde (violone), Soren Christian Vestergaard (organ), Bo Holten (conductor) DKDR 12:50 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Symphony no 104 in D major "London" (H.1.104) Tamas Vasary (conductor), Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra HUMR 01:15 AM Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957) Piano Quintet in E major, Op 15 Daniel Bard (violin), Tim Crawford (violin), Mark Holloway (viola), Chiara Enderle (cello), Paolo Giacometti (piano) CHSRF 01:47 AM Barbara Strozzi (1619-1677) "Hor che Apollo" - Serenade for Soprano, 2 violins & continuo Susanne Ryden (soprano), Musica Fiorita, Daniela Dolci (director) DEWDR 02:01 AM Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Ma mère l'oye (suite) WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:18 AM Francis Poulenc (1899-1963) Concerto for Two Pianos in D minor, FP 61 Lucas Jussen (piano), Arthur Jussen (piano), WDR Radio Orchestra, Cologne, Christoph Eschenbach (conductor) DEWDR 02:38 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Symphony No. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Martinu° Classics Cello Concertos Cello Concertino

martinu° Classics cello concertos cello concertino raphael wallfisch cello czech philharmonic orchestra jirˇí beˇlohlávek CHAN 10547 X Bohuslav Martinů in Paris, 1925 Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Concerto No. 1, H 196 (1930; revised 1939 and 1955)* 26:08 for Cello and Orchestra 1 I Allegro moderato 8:46 2 II Andante moderato 10:20 3 III Allegro – Andantino – Tempo I 7:00 Concerto No. 2, H 304 (1944 – 45)† 36:07 © P.B. Martinů/Lebrecht© P.B. Music & Arts Photo Library for Cello and Orchestra 4 I Moderato 13:05 5 II Andante poco moderato 14:10 6 III Allegro 8:44 7 Concertino, H 143 (1924)† 13:54 in C minor • in c-Moll • en ut mineur for Cello, Wind Instruments, Piano and Percussion Allegro TT 76:27 Raphael Wallfisch cello Czech Philharmonic Orchestra Bohumil Kotmel* • Josef Kroft† leaders Jiří Bělohlávek 3 Miloš Šafránek, in a letter that year: ‘My of great beauty and sense of peace. Either Martinů: head wasn’t in order when I re-scored it side lies a boldly angular opening movement, Cello Concertos/Concertino (originally) under too trying circumstances’ and a frenetically energetic finale with a (war clouds were gathering over Europe). He contrasting lyrical central Andantino. Concerto No. 1 for Cello and Orchestra had become reasonably well established in set about producing a third version of his Bohuslav Martinů was a prolific writer of Paris and grown far more confident about his Cello Concerto No. 1, removing both tuba and Concerto No. 2 for Cello and Orchestra concertos and concertante works. Among own creative abilities; he was also receiving piano from the orchestra but still keeping its In 1941 Martinů left Paris for New York, just these are four for solo cello, and four in which much moral support from many French otherwise larger format: ahead of the Nazi occupation. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Alexej Gerassimez, Percussionist & Composer

Alexej Gerassimez, Percussionist & Composer Percussionist Alexej Gerassimez, born 1987 in Essen, Germany, is as multi-faceted as the instruments he works with. His repertoire ranges from classical to contemporary and jazz to minimal music whilst also performing his own works. Alexej Gerassimez performs as a guest soloist with internationally renowned orchestras including those of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, the SWR Radio Symphony Orchestra Stuttgart and the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin under the direction of conductors such as Gerd Albrecht, Tan Dun, Kristjan Järvi, Eivind Gullberg Jensen and Michel Tabachnik. In addition, Alexej Gerassimez creates solo programmes and participates as an enthusiastic chamber musician in a vast variety of ensembles. His partners include the pianists Arthur and Lucas Jussen, the jazz pianist Omer Klein and the SIGNUM saxophone quartet. In the new concept program “Genesis of Percussion” Alexej Gerassimez and his percussion group take the audience on a discovery voyage through a wide variety of rhythmic and stylistic cultures, making the origin of sounds and rhythms within our everyday environment visible. Concerts in 2019 lead the ensemble to the Prinzregententheater Munich, the Konzerthaus Dortmund, the Tonhalle Düsseldorf and the Heidelberger Frühling. Other highlights of the 2018-2019 season include his Japan debut, the beginning of a three-year residency at the Konzerthaus Dortmund as “Junger Wilder” and the beginning as a stART artist of Bayer Kultur in Leverkusen. His own compositions are characterized by the exploration of rhythmic and acoustic possibilities as well as by the creation of individual sounds and the joy of crossing borders. Accordingly, Alexej Gerassimez integrates not only the usual percussion and melody instruments but also objects from different contexts such as bottles, brake discs, barrels or ship propellers. -

Leseprobe © Verlag Ludwig, Kiel

Leseprobe © Verlag Ludwig, Kiel Vom Pommerschen Krummstiel nach Sanssouci Leseprobe © Verlag Ludwig, Kiel Die Schirmherrschaft zur Jühlke-Ehrung der Stadt Barth und zum Ausstellungsprojekt Vom Pommerschen Krummstiel bis Sanssouci Ferdinand Jühlke (1815–1893) – ein Leben für den Garten(bau) – in den Jahren 2015–2016 hat der Minister für Wirtschaft, Bau und Tourismus des Landes Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Herr Harry Glawe, übernommen. Die Ausstellungen und die Begleitpublikation werden unterstützt durch den Landkreis Vorpommern-Rügen und Landrat Herrn Ralf Drescher. Die Ausstellung wird organisiert und getragen von der Stadt Barth und Bürgermeister Dr. Stefan Kerth. Leseprobe © Verlag Ludwig, Kiel Gerd-Helge Vogel VOM POMMERSCHEN KRUMMSTIEL NACH SANSSOUCI Ferdinand Jühlke (1815-1893) Ein Leben für den Garten(bau) Leseprobe © Verlag Ludwig, Kiel Begleitbuch zur Sonderausstellung Vom Pommerschen Krummstiel bis Sanssouci Ferdinand Jühlke (1815–1893) – ein Leben für den Garten(bau) – zum 200. Geburtstag des königlich preußischen Hofgartendirektors Ausstellung in zwei Teilen: Ausstellung Teil I: Pommerscher Krummstiel Ferdinand Jühlke als Gartenbauer an der Königlichen Landwirtschaftlichen Akademie Greifswald-Eldena und als Chronist des Gartenbaus in Neuvorpommern und Rügen 1. September 2015 – 2. November 2015 Ausstellung Teil II: Sanssouci Ferdinand Jühlke als visionärer Gartenbaulehrer und traditioneller Gartengestalter in Preußen und Europa: »Utile dulci – Nützlich und schön.« Juni 2016 – November 2016 im Vineta-Museum der Stadt Barth, Lange Straße 16, 18356 Barth, T 038231 81771, [email protected] Herausgeber: Dr. Gerd Albrecht Vineta-Museum, Barth im Auftrag der Stadt Barth Konzeption und Gesamtleitung der Ausstellung: Dr. Gerd Albrecht in Zusammenarbeit mit PD Dr. Gerd-Helge Vogel Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. -

Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian Art Scene: How to Become a Brazilian Musician*

1 Mana vol.1 no.se Rio de Janeiro Oct. 2006 Heitor Villa-Lobos and the Parisian art scene: how to become a Brazilian musician* Paulo Renato Guérios Master’s in Social Anthropology at PPGAS/Museu Nacional/UFRJ, currently a doctoral student at the same institution ABSTRACT This article discusses how the flux of cultural productions between centre and periphery works, taking as an example the field of music production in France and Brazil in the 1920s. The life trajectories of Jean Cocteau, French poet and painter, and Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian composer, are taken as the main reference points for the discussion. The article concludes that social actors from the periphery tend themselves to accept the opinions and judgements of the social actors from the centre, taking for granted their definitions concerning the criteria that validate their productions. Key words: Heitor Villa-Lobos, Brazilian Music, National Culture, Cultural Flows In July 1923, the Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos arrived in Paris as a complete unknown. Some five years had passed since his first large-scale concert in Brazil; Villa-Lobos journeyed to Europe with the intention of publicizing his musical output. His entry into the Parisian art world took place through the group of Brazilian modernist painters and writers he had encountered in 1922, immediately before the Modern Art Week in São Paulo. Following his arrival, the composer was invited to a lunch in the studio of the painter Tarsila do Amaral where he met up with, among others, the poet Sérgio Milliet, the pianist João de Souza Lima, the writer Oswald de Andrade and, among the Parisians, the poet Blaise Cendrars, the musician Erik Satie and the poet and painter Jean Cocteau. -

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism

Nationalism, Primitivism, & Neoclassicism" Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)! Biographical sketch:! §" Born in St. Petersburg, Russia.! §" Studied composition with “Mighty Russian Five” composer Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov.! §" Emigrated to Switzerland (1910) and France (1920) before settling in the United States during WW II (1939). ! §" Along with Arnold Schönberg, generally considered the most important composer of the first half or the 20th century.! §" Works generally divided into three style periods:! •" “Russian” Period (c.1907-1918), including “primitivist” works! •" Neoclassical Period (c.1922-1952)! •" Serialist Period (c.1952-1971)! §" Died in New York City in 1971.! Pablo Picasso: Portrait of Igor Stravinsky (1920)! Ballets Russes" History:! §" Founded in 1909 by impresario Serge Diaghilev.! §" The original company was active until Diaghilev’s death in 1929.! §" In addition to choreographing works by established composers (Tschaikowsky, Rimsky- Korsakov, Borodin, Schumann), commissioned important new works by Debussy, Satie, Ravel, Prokofiev, Poulenc, and Stravinsky.! §" Stravinsky composed three of his most famous and important works for the Ballets Russes: L’Oiseau de Feu (Firebird, 1910), Petrouchka (1911), and Le Sacre du Printemps (The Rite of Spring, 1913).! §" Flamboyant dancer/choreographer Vaclav Nijinsky was an important collaborator during the early years of the troupe.! ! Serge Diaghilev (1872-1929) ! Ballets Russes" Serge Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsky.! Stravinsky with Vaclav Nijinsky as Petrouchka (Paris, 1911).! Ballets -

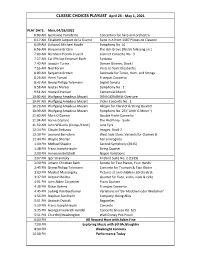

Apr 26 to May 2.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES PLAYLIST April 26 - May 1, 2021 PLAY DATE: Mon, 04/26/2021 6:00 AM Germaine Tailleferre Concertino for harp and orchestra 6:17 AM Elisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre Suite in A from 1687 Pièces de Clavecin 6:39 AM (Johann) Michael Haydn Symphony No. 40 6:56 AM Benjamin Britten The Ash Grove (Welsh folksong arr.) 7:00 AM Bernhard Henrik Crusell Clarinet Concerto No. 3 7:27 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Fantasia 7:40 AM Joaquin Turina Dances Gitanes, Book I 7:55 AM Ned Rorem Visits to Saint Elizabeth's 8:00 AM Benjamin Britten Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings 8:26 AM Henri Tomasi Trumpet Concerto 8:42 AM Georg Philipp Telemann Septet Sonata 8:58 AM Gustav Mahler Symphony No. 1 9:51 AM Howard Hanson Centennial March 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI: Overture 10:07 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 10:29 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Allegro for Clarinet & String Quartet 10:39 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 25 ("Little G Minor") 11:00 AM Mark O'Connor Double Violin Concerto 11:34 AM Aaron Copland The Red Pony - Suite 11:59 AM John Williams (Comp./Cond.) Jane Eyre 12:14 PM Claude Debussy Images: Book 2 12:30 PM Leonard Bernstein West Side Story: Variants for Clarinet & 12:44 PM Wayne Shorter Terra Incognita 1:00 PM Michael Shapiro Second Symphony (2015) 1:38 PM Franz Joseph Haydn String Quartet 2:00 PM Hermann Bellstedt Napoli Variations 2:07 PM Igor Stravinsky Firebird Suite No. -

Kalendár Výročí

Č KALENDÁR VÝROČÍ 2010 H U D B A Zostavila Mgr. Dana Drličková Bratislava 2009 Pouţité skratky: n. = narodil sa u. = umrel výr.n. = výročie narodenia výr.ú. = výročie úmrtia 3 Ú v o d 6.9.2007 oznámili svetové agentúry, ţe zomrel Luciano Pavarotti. A hudobný svet stŕpol… Muţ, ktorý sa narodil ako syn pekára a zomrel ako hudobná superstar. Muţ, ktorého svetová popularita nepramenila len z jeho výnimočného tenoru, za ktorý si vyslúţil označenie „kráľ vysokého cé“. Jeho zásluhou sa opera ako okrajový ţáner predrala do povedomia miliónov poslucháčov. Exkluzívny svet klasickej hudby priblíţil širokému publiku vystúpeniami v športových halách, účinkovaním s osobnosťami popmusik, či rocku a charitatívnymi koncertami. Spieval takmer výhradne taliansky repertoár, debutoval roku 1961 v úlohe Rudolfa v Pucciniho Bohéme na scéne Teatro Municipal v Reggio Emilia. Jeho ľudská tvár otvárala srdcia poslucháčov: bol milovníkom dobrého jedla, futbalu, koní, pekného oblečenia a tieţ obstojný maliar. Bol poverčivý – musel mať na vystú- peniach vţdy bielu vreckovku v ruke a zahnutý klinec vo vrecku. V nastupujúcom roku by sa bol doţil 75. narodenín. Luciano Pavarotti patrí medzi najväčších tenoristov všetkých čias a je jednou z mnohých osobností, ktorých výročia si budeme v roku 2010 pripomínať. Nedá sa v úvode venovať detailnejšie ţiadnemu z nich, to ani nie je cieľom tejto publikácie. Ţivoty mnohých pripomínajú román, ľudské vlastnosti snúbiace sa s géniom talentu, nie vţdy v ideálnom pomere. Ale to je uţ úlohou muzikológov, či licenciou spisovateľov, spracovať osudy osobností hudby aj z tých, zdanlivo odvrátených stránok pohľadu ... V predkladanom Kalendári výročí uţ tradične upozorňujeme na výročia narodenia či úmrtia hudobných osobností : hudobných skladateľov, dirigentov, interprétov, teoretikov, pedagógov, muzikológov, nástrojárov, folkloristov a ďalších. -

Nn Arbor 'Ummer >Oc

nn Arbor 'ummer >oc THE UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN presents Junge Deutsche Philharmonic GERD ALBRECHT Conductor GIDON KREMER, Violinist Monday Evening, July 22, 1985, at 8:00 Power Center for the Performing Arts, Ann Arbor, Michigan Offertorium, Concerto for Violin and Orchestra ................ Sofia Gubaidulina In three parts, played without pause Gidon Kremer, Violinist I N.T E R M I S S I O N Symphony No. 3 in D minor ................................. Anton Bruckner Massig bewegt Adagio quasi andante Scherzo Finale: allegro Sofia Gubaidulina was born in 1931 in Christopol, a small town not far from the Ural Moun tains in the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Republic. She studied piano as a child and "immediately understood that music was to be my profession." After moving to Kazan for several years of study at the Kazan Conservatory, she transferred to the Moscow Conservatory for eight years of undergraduate and graduate study in composition. Her compositions include chamber music for a wide variety of instruments, orchestral works, concerti, and several works for voice and orchestra. Offertorium was completed in 1980, written for, and dedicated to, Gidon Kremer. Kremer introduced the score to the West in Vienna and later presented it in Berlin. On January 3, 1985, Kremer and the New York Philharmonic, under Zubin Mehta, gave the piece its United States premiere in New York's Avery Fisher Hall. Of Offertorium, Harlow Robinson wrote in Musical America: "Although in three parts, the work does not conform to the conventions of the classical-romantic concerto, and Gubaidulina prefers to think of it as a Marge symphonic piece with the violin simply the leading character.' It makes great demands on the soloist, who must produce a sound by turns dry and expansive.