The Virtual Speech Community: Social Network and Language Variation on IRC John C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

The Intersection of Sex and Social Class in the Course of Linguistic Change

Language Variation and Change, 2 (1990), 205-254. Printed in the U.S.A. © 1991 Cambridge University Press 0954-3945/91 $5.00 + .00 The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change WILLIAM LABOV University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT Two general principles of sexual differentiation emerge from previous socio- linguistic studies: that men use a higher frequency of nonstandard forms than women in stable situations, and that women are generally the innovators in lin- guistic change. It is not clear whether these two tendencies can be unified, or how differences between the sexes can account for the observed patterns of lin- guistic change. The extensive interaction between sex and other social factors raises the issue as to whether the curvilinear social class pattern associated with linguistic change is the product of a rejection of female-dominated changes by lower-class males. Multivariate analysis of data from the Philadelphia Project on Linguistic Change and Variation indicates that sexual differentiation is in- dependent of social class at the beginning of a change, but that interaction de- velops gradually as social awareness of the change increases. It is proposed that sexual differentiation of language is generated by two distinct processes: (1) for all social classes, the asymmetric context of language learning leads to an ini- tial acceleration of female-dominated changes and retardation of male-domi- nated changes; (2) women lead men in the rejection of linguistic changes as they are recognized by the speech community, a differentiation that is maximal for the second highest status group. SOME BASIC FINDINGS AND SOME BASIC PROBLEMS Among the clearest and most consistent results of sociolinguistic research in the speech community are the findings concerning the linguistic differenti- ation of men and women. -

Speech Community. the Second Perspective Refers to the Notion of Language and Discourse As a Way of Representing (Hall 1996; Foucault 1972)

Duranti / Companion to Linguistic Anthropology Final 12.11.2003 1:27pm page 3 Speech CHAPTER 1 Community Marcyliena Morgan 1INTRODUCTION This chapter focuses on how the concept speech community has become integral to the interpretation and representation of societies and situations marked by change, diver- sity, and increasing technology as well as those situations previously treated as conventional. The study of the speech community is central to the understanding of human language and meaning-making because it is the product of prolonged interaction among those who operate within shared belief and value systems regarding their own culture, society, and history as well as their communication with others. These interactions constitute the fundamental nature of human contact and the importance of language, discourse, and verbal styles in the representation and negotiation of the relationships that ensue. Thus the concept of speech community does not simply focus on groups that speak the same language. Rather, the concept takes as fact that language represents, embodies, constructs, and constitutes mean- ingful participation in a society and culture. It also assumes that a mutually intelligible symbolic and ideological communicative system must be at play among those who share knowledge and practices about how one is meaningful across social contexts.1 Thus it is within the speech community that identity, ideology, and agency (see Bucholtz and Hall, Kroskrity, and Duranti, this volume) are actualized in society. While there are many social and political forms a speech community may take – from nation-states to chat rooms dedicated to pet psychology – speech communities are recognized as distinctive in relation to other speech communities. -

23 the Speech Community

23 The Speech Community PETER L. PATRICK The speech community (SpCom), a core concept in empirical linguistics, is the intersection of many principal problems in sociolinguistic theory and method. I trace its history of development and divergence, survey general problems with contemporary notions, and discuss links to key issues in investigating language variation and change. I neither offer a new and correct definition nor reject the concept (both misguided efforts), nor exhaustively survey its applica- tions in the field (an impossibly large task). 1 General Problems with Speech Community as a Concept Every branch of linguistics that is concerned with representative samples of a population; that takes individual speakers or experimental subjects as typical members of a group; that studies langue as attributable to a socially coherent body (whether or not it professes interest in the social nature of that body); or that takes as primitive such notions as “native speaker,” “competence/ performance,” “acceptability,” etc., which manifestly refer to collective behavior, rests partially on a concept equivalent to the SpCom. Linguistic systems are exercised by speakers, in social space: there they are acquired, change, are manipulated for expressive or communicative purposes, undergo attrition, etc. Whether linguists prefer to focus on speakers, varieties or grammars, the prob- lem of relating a linguistic system to its speakers is not trivial. In studying language change and variation (geographical or social), refer- ence to the SpCom is inescapable, yet there is remarkably little agreement or theoretical discussion of the concept in sociolinguistics, though it has often been defined. Some examples from research reports suggest the degree of its (over-)extension (Williams 1992: 71). -

“Code Switching” in Sociocultural Linguistics Chad Nilep University of Colorado, Boulder

“Code Switching” in Sociocultural Linguistics Chad Nilep University of Colorado, Boulder This paper reviews a brief portion of the literature on code switching in sociology, linguistic anthropology, and sociolinguistics, and suggests a definition of the term for sociocultural analysis. Code switching is defined as the practice of selecting or altering linguistic elements so as to contextualize talk in interaction. This contextualization may relate to local discourse practices, such as turn selection or various forms of bracketing, or it may make relevant information beyond the current exchange, including knowledge of society and diverse identities. Introduction The term code switching (or, as it is sometimes written, code-switching or codeswitching)1 is broadly discussed and used in linguistics and a variety of related fields. A search of the Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts database in 2005 shows more than 1,800 articles on the subject published in virtually every branch of linguistics. However, despite this ubiquity – or perhaps in part because of it – scholars do not seem to share a definition of the term. This is perhaps inevitable, given the different concerns of formal linguists, psycholinguists, sociolinguists, philosophers, anthropologists, etc. This paper will attempt to survey the use of the term code switching in sociocultural linguistics and suggest useful definitions for sociocultural work. Since code switching is studied from so many perspectives, this paper will necessarily seem to omit important elements of the literature. Much of the work labeled “code switching” is interested in syntactic or morphosyntactic constraints on language alternation (e.g. Poplack 1980; Sankoff and Poplack 1981; Joshi 1985; Di Sciullo and Williams 1987; Belazi et al. -

Speech Community and SLA

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 4, No. 6, pp. 1327-1331, November 2013 © 2013 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.4.6.1327-1331 Speech Community and SLA Changjuan Zhan School of Foreign Languages, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong, China Abstract—The notion of the speech community is one of the foci and the main issue of analysis in the ethnography of communication and one of the important concepts in sociolinguistics. In the theory and method of sociolinguistics, it is one of the major problems concerned. Second language acquisition (SLA) is a sub-discipline of applied linguistics and is defined as the learning and adopting of a language that is not your native language as well as the process by which people learn it. SLA is influenced by many factors in a speech community. This paper presents a detailed analysis of speech community; discusses different theories concerning SLA; summarizes the various factors in a speech community which function to influence SLA; and tries to point out the significance of the study and the problems existing in it. Index Terms—speech community, second language acquisition, definition, influence, sociolinguistic I. INTRODUCTION In most sociolinguistic and anthropological-linguistic research, the speech community has always been the focus. It is one of the main problems and the major objective of study in the ethnography of communication, in addition, it is also one of the important issues in sociolinguistics. In the theory and method of sociolinguistics, it is one of the major problems concerned. -

Dialect Accent Sociolinguistics: What Is It? Language Variation

Sociolinguistics: What is it? Dialect Any variety of a language characterized by systematic differences in • Language does not exist in a vacuum. pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary from other varieties of the same language is called a dialect. • Since language is a social phenomenon it is natural to assume that the Everyone speaks a dialect – in fact, many dialects at different levels. The structure of a society has some impact on the language of the speakers people who speak a certain dialect are called a speech community. of that society. Some of the larger dialectal divisions in the English speaking world: British • The study of this relationship and of other extralinguistic factors is the English vs. American English vs. Australian English (along with others). subfield of sociolinguistics. Northern American English, Southern American English, etc. • We will look in this section at the ways in which languages vary internally, (1) Brit/American: lay by/rest area, petrol/gasoline, lorry/truck, and at the factors which create/sustain such variation. minerals/soft drinks • This will give us a greater understanding of and tolerance for the A dialect spoken by one individual is called an idiolect. Everyone has small differences between the speech of individuals and groups. differences between the way they talk and the way even their family and best friends talk, creating a “minimal dialect”. Linguistics 201, Detmar Meurers Handout 15 (May 2, 2004) 1 3 Language Variation Accent What Factors Enter into Language Variation? • An accent is a certain form of a language spoken by a subgroup of • It’s clear that there are many systematic differences between different speakers of that language which is defined by phonological features. -

Code-Switching, Identity, and Globalization

JWST555-28 JWST555-Tannen March 11, 2015 10:3 Printer Name: Yet to Come Trim: 244mm × 170mm 28 Code-Switching, Identity, and Globalization KIRA HALL AND CHAD NILEP 0 Introduction1 Although scholarship in discourse analysis has traditionally conceptualized interac- tion as taking place in a single language, a growing body of research in sociocultural linguistics views multilingual interaction as a norm instead of an exception. Linguistic scholarship acknowledging the diversity of sociality amid accelerating globalization has focused on linguistic hybridity instead of uniformity, movement instead of stasis, and borders instead of interiors. This chapter seeks to address how we have arrived at this formulation through a sociohistorical account of theoretical perspectives on dis- cursive practices associated with code-switching. We use the term broadly in this chapter to encompass the many kinds of language alternations that have often been subsumed under or discussed in tandem with code-switching, among them borrowing, code-mixing, interference, diglossia, style-shifting, crossing, mock language, bivalency,andhybridity. Language alternation has been recognized since at least the mid-twentieth century as an important aspect of human language that should be studied. Vogt (1954), for example, suggested that bilingualism should be “of great interest to the linguist” since language contact has probably had an effect on all languages. Still, language contact in these early studies is most often portrayed as an intrusion into the monolingual interior of a bounded language. Indeed, the century-old designation of foreign-derived vocabulary as loan words or borrowings promotes the idea that languages are distinct entities: lexemes are like objects that can be adopted by another language to fill expressive needs, even if they never quite become part of the family. -

89 Annual Meeting

Meeting Handbook Linguistic Society of America American Dialect Society American Name Society North American Association for the History of the Language Sciences Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas The Association for Linguistic Evidence 89th Annual Meeting UIF+/0 7/-+Fi0N i0N XgLP(+I'L 5/hL- 7/-+Fi0N` 96 ;_AA Ti0(i-e` @\A= ANNUAL REVIEWS It’s about time. Your time. It’s time well spent. VISIT US IN BOOTH #1 LEARN ABOUT OUR NEW JOURNAL AND ENTER OUR DRAWING! New from Annual Reviews: Annual Review of Linguistics linguistics.annualreviews.org • Volume 1 • January 2015 Co-Editors: Mark Liberman, University of Pennsylvania and Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts Amherst The Annual Review of Linguistics covers significant developments in the field of linguistics, including phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and their interfaces. Reviews synthesize advances in linguistic theory, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, neurolinguistics, language change, biology and evolution of language, typology, and applications of linguistics in many domains. Complimentary online access to the first volume will be available until January 2016. TABLE OF CONTENTS: • Suppletion: Some Theoretical Implications, • Correlational Studies in Typological and Historical Jonathan David Bobaljik Linguistics, D. Robert Ladd, Seán G. Roberts, Dan Dediu • Ditransitive Constructions, Martin Haspelmath • Advances in Dialectometry, Martijn Wieling, John Nerbonne • Quotation and Advances in Understanding Syntactic • Sign Language Typology: The Contribution of Rural Sign Systems, Alexandra D'Arcy Languages, Connie de Vos, Roland Pfau • Semantics and Pragmatics of Argument Alternations, • Genetics and the Language Sciences, Simon E. Fisher, Beth Levin Sonja C. -

Norms and Sociolinguistic Description1

Irina Kauhanen Norms and Sociolinguistic Description1 Abstract This article considers the status of norms in sociolinguistic description, more precisely variationist research. The discussion in this paper is structured around Labov’s definition of speech community. The definition not only aroused intense discussion within the paradigm on the nature of norms but also steered the subsequent research theoretically and methodologically. By briefly reviewing the theoretical debate concerning norms and studying some of the central concepts in empirical sociolinguistics, this article examines what kind of picture the theoretical and methodological background of the variationist paradigm depicts on language norms. 1. Introduction Social life, including language use, is governed by norms—socially shared concepts of appropriate and expected behavior. The most basic of these concepts are acquired in early childhood through socialization. In the case of language norms this means that the first language norms adopted are the ones of everyday spoken language. Compared to the prescriptive norms of the standardized language, these uncodified norms are perhaps less conscious yet more natural (Karlsson 1995: 170) in every sense of the word: they are more numerous, acquired earlier in life and mastered by all native speakers. They also historically precede the norms of the standard language and in communities without a written language they are the only norms available. Fred Karlsson (1995) has stressed the importance of these naturally occurring norms for linguistic description. He both encourages to take the norms of the vernacular as the basis of grammatical description as well as to discuss more thoroughly the nature of language norms. Norms are inherently social. -

1 Lexis and Sociolinguistics English Language and Applied Linguistics

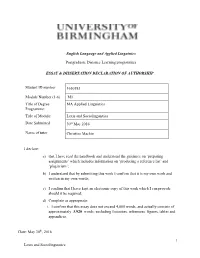

English Language and Applied Linguistics Postgraduate Distance Learning programmes ESSAY & DISSERTATION DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP Student ID number 1650583 Module Number (1-6) M1 Title of Degree MA Applied Linguistics Programme: Title of Module: Lexis and Sociolinguistics Date Submitted 30th May 2016 Name of tutor Christine Mackie I declare: a) that I have read the handbook and understand the guidance on ‘preparing assignments’ which includes information on ‘producing a reference list’ and ‘plagiarism’; b) I understand that by submitting this work I confirm that it is my own work and written in my own words; c) I confirm that I have kept an electronic copy of this work which I can provide should it be required; d) Complete as appropriate: i. I confirm that this essay does not exceed 4,000 words, and actually consists of approximately 3,920 words; excluding footnotes, references, figures, tables and appendices. Date: May 30th, 2016 1 Lexis and Sociolinguistics Table of Contents Section Page 1. Introduction 3 2. What is diglossia? 3 2.1. Definition of diglossia 3 2.2. H(igh) variety and L(ow) variety: separation of functions and perceived identities 4 2.3. Features of diglossia 5 3. The features of diglossia within a speech community 6 3.1. The speech communities under investigation 6 3.1.1. African-American Vernacular English and Standard American English 6 3.1.2. Haitian Creole and Standard French 7 3.2. The origin of diglossia and the loss of identity 9 4. Diglossia as a reflection of social and linguistic oppression of one speech community by another 10 4.1. -

African American Vernacular English Erik R

Language and Linguistics Compass 1/5 (2007): 450–475, 10.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00029.x PhonologicalErikBlackwellOxford,LNCOLanguage1749-818x©Journal02910.1111/j.1749-818x.2007.00029.xAugust0450???475???Original 2007 Thomas 2007 UKThecompilationArticles Publishing and Authorand Linguistic Phonetic © Ltd 2007 CharacteristicsCompass Blackwell Publishing of AAVE Ltd Phonological and Phonetic Characteristics of African American Vernacular English Erik R. Thomas* North Carolina State University Abstract The numerous controversies surrounding African American Vernacular English can be illuminated by data from phonological and phonetic variables. However, what is known about different variables varies greatly, with consonantal variables receiving the most scholarly attention, followed by vowel quality, prosody, and finally voice quality. Variables within each domain are discussed here and what has been learned about their realizations in African American speech is compiled. The degree of variation of each variable within African American speech is also summarized when it is known. Areas for which more work is needed are noted. Introduction Much of the past discussion of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) has dealt with morphological and syntactic variables. Such features as the invariant be (We be cold all the time), copula deletion (We cold right now), third-person singular -s absence (He think he look cool) and ain’t in place of didn’t (He ain’t do it) are well known among sociolinguists as hallmarks of AAVE (e.g. Fasold 1981). Nevertheless, phonological and phonetic variables characterize AAVE just as much as morphosyntactic ones, even though consonantal variables are the only pronunciation variables in AAVE that have attracted sustained attention. AAVE has been at the center of a series of controversies, all of which are enlightened by evidence from phonology and phonetics.