The Cases of the Limburgs and Swabian Speech Communities in Australia1 Diglossia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language: Did You Know?

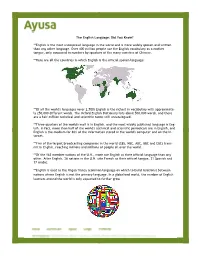

The English Language: Did You Know? **English is the most widespread language in the world and is more widely spoken and written than any other language. Over 400 million people use the English vocabulary as a mother tongue, only surpassed in numbers by speakers of the many varieties of Chinese. **Here are all the countries in which English is the official spoken language: **Of all the world's languages (over 2,700) English is the richest in vocabulary with approximate- ly 250,000 different words. The Oxford English Dictionary lists about 500,000 words, and there are a half-million technical and scientific terms still uncatalogued. **Three-quarters of the world's mail is in English, and the most widely published language is Eng- lish. In fact, more than half of the world's technical and scientific periodicals are in English, and English is the medium for 80% of the information stored in the world's computer and on the In- ternet. **Five of the largest broadcasting companies in the world (CBS, NBC, ABC, BBC and CBC) trans- mit in English, reaching millions and millions of people all over the world. **Of the 163 member nations of the U.N., more use English as their official language than any other. After English, 26 nations in the U.N. cite French as their official tongue, 21 Spanish and 17 Arabic. **English is used as the lingua franca (common language on which to build relations) between nations where English is not the primary language. In a globalized world, the number of English learners around the world is only expected to further grow. -

Attitudes Towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible

Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Power, Cian Joseph. 2015. Many Peoples of Obscure Speech and Difficult Language: Attitudes towards Linguistic Diversity in the Hebrew Bible. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:23845462 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE A dissertation presented by Cian Joseph Power to The Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2015 © 2015 Cian Joseph Power All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Peter Machinist Cian Joseph Power MANY PEOPLES OF OBSCURE SPEECH AND DIFFICULT LANGUAGE: ATTITUDES TOWARDS LINGUISTIC DIVERSITY IN THE HEBREW BIBLE Abstract The subject of this dissertation is the awareness of linguistic diversity in the Hebrew Bible—that is, the recognition evident in certain biblical texts that the world’s languages differ from one another. Given the frequent role of language in conceptions of identity, the biblical authors’ reflections on language are important to examine. -

Standard Languages and Language Standards

Standard Languages and Language Standards Gramley, WS 2008-09 Yiddish Divisions of Jewry Sephardim: Spanish-Portugese Jews (and exiled Jews from there) As(h)kinazim: German (or northern European) Jews Mizrhim: Northern African and Arabian Jews "Jewish" languages Commonly formed from the vernacular languages of the larger communities in which Jews lived. Ghettoization and self-segregation led to differences between the local vernaculars and Jews varieties of these languages. Linguistically different because of the addition of Hebrew words, such as meshuga, makhazor (prayer book for the High Holy Days), or beis hakneses (synagogue) Among the best known such languages are Yiddish and Ladino (the Balkans, esp. Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, the Maghreb – Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492). In biblical times the Jews spoke Hebrew, then Aramaic, later Greek (and so on). Today Hebrew has been revived in the form of Ivrit (= Modern Hebrew). We will be looking at Yiddish. ( ייִדיש) Yiddish The focus on Yiddish is concerned chiefly with the period prior to the Second World War and the Holocaust. Yiddish existed as a language with a wide spread of dialects: Western Yiddish • Northwestern: Northern Germany and the Netherlands • Midwestern: Central Germany • Southwestern: Southern Germany, France (including Judea-Alsatian), Northern Italy Eastern Yiddish This was the larger of the two branches, and without further explanation is what is most often meant when referring to Yiddish. • Northeastern or Litvish: the Baltic states, Belarus • Mideastern or Poylish: Poland and Central Europe • Southeastern or Ukrainish: Ukraine and the Balkans • Hungarian: Austro-Hungarian Empire Standardization The move towards standardization was concentrated most importantly in the first half of the twentieth century. -

The Intersection of Sex and Social Class in the Course of Linguistic Change

Language Variation and Change, 2 (1990), 205-254. Printed in the U.S.A. © 1991 Cambridge University Press 0954-3945/91 $5.00 + .00 The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change WILLIAM LABOV University of Pennsylvania ABSTRACT Two general principles of sexual differentiation emerge from previous socio- linguistic studies: that men use a higher frequency of nonstandard forms than women in stable situations, and that women are generally the innovators in lin- guistic change. It is not clear whether these two tendencies can be unified, or how differences between the sexes can account for the observed patterns of lin- guistic change. The extensive interaction between sex and other social factors raises the issue as to whether the curvilinear social class pattern associated with linguistic change is the product of a rejection of female-dominated changes by lower-class males. Multivariate analysis of data from the Philadelphia Project on Linguistic Change and Variation indicates that sexual differentiation is in- dependent of social class at the beginning of a change, but that interaction de- velops gradually as social awareness of the change increases. It is proposed that sexual differentiation of language is generated by two distinct processes: (1) for all social classes, the asymmetric context of language learning leads to an ini- tial acceleration of female-dominated changes and retardation of male-domi- nated changes; (2) women lead men in the rejection of linguistic changes as they are recognized by the speech community, a differentiation that is maximal for the second highest status group. SOME BASIC FINDINGS AND SOME BASIC PROBLEMS Among the clearest and most consistent results of sociolinguistic research in the speech community are the findings concerning the linguistic differenti- ation of men and women. -

Speech Community. the Second Perspective Refers to the Notion of Language and Discourse As a Way of Representing (Hall 1996; Foucault 1972)

Duranti / Companion to Linguistic Anthropology Final 12.11.2003 1:27pm page 3 Speech CHAPTER 1 Community Marcyliena Morgan 1INTRODUCTION This chapter focuses on how the concept speech community has become integral to the interpretation and representation of societies and situations marked by change, diver- sity, and increasing technology as well as those situations previously treated as conventional. The study of the speech community is central to the understanding of human language and meaning-making because it is the product of prolonged interaction among those who operate within shared belief and value systems regarding their own culture, society, and history as well as their communication with others. These interactions constitute the fundamental nature of human contact and the importance of language, discourse, and verbal styles in the representation and negotiation of the relationships that ensue. Thus the concept of speech community does not simply focus on groups that speak the same language. Rather, the concept takes as fact that language represents, embodies, constructs, and constitutes mean- ingful participation in a society and culture. It also assumes that a mutually intelligible symbolic and ideological communicative system must be at play among those who share knowledge and practices about how one is meaningful across social contexts.1 Thus it is within the speech community that identity, ideology, and agency (see Bucholtz and Hall, Kroskrity, and Duranti, this volume) are actualized in society. While there are many social and political forms a speech community may take – from nation-states to chat rooms dedicated to pet psychology – speech communities are recognized as distinctive in relation to other speech communities. -

Department of English and American Studies English Language And

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Jana Krejčířová Australian English Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph. D. 2016 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor PhDr. Kateřina Tomková, Ph.D. for her patience and valuable advice. I would also like to thank my partner Martin Burian and my family for their support and understanding. Table of Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................................................... 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. AUSTRALIA AND ITS HISTORY ................................................................. 10 1.1. Australia before the arrival of the British .................................................... 11 1.1.1. Aboriginal people .............................................................................. 11 1.1.2. First explorers .................................................................................... 14 1.2. Arrival of the British .................................................................................... 14 1.2.1. Convicts ............................................................................................. 15 1.3. Australia in the -

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri Scholarworks User Guide August, 2020

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri ScholarWorks User Guide August, 2020 Table of Contents INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 1 THE RECORDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 THE SPEAKERS ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 KANSAS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSOURI .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 THE QUESTIONNAIRES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 WENKER SENTENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 KU QUESTIONNAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 REFERENCE MAPS FOR LOCATING POTENTIAL SPEAKERS ..................................................................................... -

German and English Noun Phrases

RICE UNIVERSITY German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach Ward Keith Barrows A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF 3 1272 00675 0689 Master of Arts Thesis Directors signature: / Houston, Texas April, 1971 Abstract: German and English Noun Phrases: A Transformational-Contrastive Approach, by Ward Keith Barrows The paper presents a contrastive approach to German and English based on the theory of transformational grammar. In the first chapter, contrastive analysis is discussed in the context of foreign language teaching. It is indicated that contrastive analysis in pedagogy is directed toward the identification of sources of interference for students of foreign languages. It is also pointed out that some differences between two languages will prove more troublesome to the student than others. The second chapter presents transformational grammar as a theory of language. Basic assumptions and concepts are discussed, among them the central dichotomy of competence vs performance. Chapter three then present the structure of a grammar written in accordance with these assumptions and concepts. The universal base hypothesis is presented and adopted. An innovation is made in the componential structire of a transformational grammar: a lexical component is created, whereas the lexicon has previously been considered as part of the base. Chapter four presents an illustration of how transformational grammars may be used contrastively. After a base is presented for English and German, lexical components and some transformational rules are contrasted. The final chapter returns to contrastive analysis, but discusses it this time from the point of view of linguistic typology in general. -

New Zealand English

New Zealand English Štajner, Renata Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2011 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:005306 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Preddiplomski studij Engleskog jezika i književnosti i Njemačkog jezika i književnosti Renata Štajner New Zealand English Završni rad Prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2011 0 Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................4 1. History and Origin of New Zealand English…………………………………………..5 2. New Zealand English vs. British and American English ………………………….….6 3. New Zealand English vs. Australian English………………………………………….8 4. Distinctive Pronunciation………………………………………………………………9 5. Morphology and Grammar……………………………………………………………11 6. Maori influence……………………………………………………………………….12 6.1.The Maori language……………………………………………………………...12 6.2.Maori Influence on the New Zealand English………………………….………..13 6.3.The -

English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate

ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 ENGLISH IN SOUTH AFRICA: EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION AND THE POLICY DEBATE INAUGURAL LECTURE DELIVERED AT RHODES UNIVERSITY on 19 May 1993 by L.S. WRIGHT BA (Hons) (Rhodes), MA (Warwick), DPhil (Oxon) Director Institute for the Study of English in Africa GRAHAMSTOWN RHODES UNIVERSITY 1993 First published in 1993 by Rhodes University Grahamstown South Africa ©PROF LS WRIGHT -1993 Laurence Wright English in South Africa: Effective Communication and the Policy Debate ISBN: 0-620-03155-7 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. Mr Vice Chancellor, my former teachers, colleagues, ladies and gentlemen: It is a special privilege to be asked to give an inaugural lecture before the University in which my undergraduate days were spent and which holds, as a result, a special place in my affections. At his own "Inaugural Address at Edinburgh" in 1866, Thomas Carlyle observed that "the true University of our days is a Collection of Books".1 This definition - beloved of university library committees worldwide - retains a certain validity even in these days of microfiche and e-mail, but it has never been remotely adequate. John Henry Newman supplied the counterpoise: . no book can convey the special spirit and delicate peculiarities of its subject with that rapidity and certainty which attend on the sympathy of mind with mind, through the eyes, the look, the accent and the manner. -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

New Zealand Ways of Speaking English Edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes

UCLA Issues in Applied Linguistics Title New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77n0788f Journal Issues in Applied Linguistics, 2(1) ISSN 1050-4273 Author Locker, Rachel Publication Date 1991-06-30 DOI 10.5070/L421005133 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REVIEWS New Zealand Ways of Speaking English edited by Allan Bell and Janet Holmes. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters, 1990. 305 pp. Reviewed by Rachel Locker University of California, Los Angeles Coming to America has resulted in an interesting encounter with my linguistic identity, my New Zealand accent regularly provoking at least two distinct reactions: either "Please say something, I love the way you talk!" (which causes me some amusement but mainly disbelief), or "Your English is very good- what's your native language?" It is difficult to review a book like New Zealand Ways of Speaking English without relating such experiences, because as a nation New Zealanders at home and abroad have long suffered from a lurking sense of inferiority about the way they speak English, especially compared with those in the colonial "homeland," i.e., England. That dialectal differences create attitudes about what is better and worse is no news to scholars of language use, but this collection of studies on New Zealand English (NZE) not only reveals some interesting peculiarities of that particular dialect and its speakers from "down- under"; it also makes accessible the significant contributions of New Zealand linguists to broader theoretical concerns in sociolinguistics and applied linguistics.