MIGRATION POLICY PRACTICE Introduction Marie Mcauliffe1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Afghan Refugee Journeys

Afghan Refugee Journeys: Onwards Migration Decision Making in Greece and Turkey Abstract This paper contributes to the lack of research on refugee journeys by examining the factors influencing Afghan refugees plans to stay in Greece or Turkey or migrate onwards as a continuation of their fragmented refugee journeys. Following from the seminal article of BenEzer and Zetter (2015) this paper examines the four conceptual challenges of refugee journeys of: temporal elements, drivers and destinations, the process of the journey and the wayfarers characteristics. Using a quantitative approach with a unique original dataset of 364 Afghans in Greece and Turkey, regression analysis is used to examine the decision making of Afghans to stay or migrate onwards within the context of the four conceptual challenges of refugee journeys. The results show that all the conceptual elements are significant in influencing Afghan decision making for the continuation of their refugee journeys. The paper further contextualizes these results and highlights policy implications. 1 Introduction Over the past decade there has been an increasing number of Afghans migrating to Greece and Turkey as they seek access to the rest of Europe. The ongoing conflict in Afghanistan including the increasing insecurity from 2008 onwards, combined with the increasingly hostile environment for Afghan refugees in Iran and recent repatriations from Pakistan, has led to continued migration movements further afield in search of safety and security. Research has demonstrated the long and arduous journeys that Afghans face in their movements to Europe (Crawley et al., 2016; Dimitraidi, 2015; Donini et al., 2016; Kaytaz, 2016; Kuschminder and Siegel, 2016; Schuster, 2011; UNHCR, 20120). -

Decision Making on the Balkan Route and the EU-Turkey

Decision Making on the Balkan Route and the EU-Turkey Statement Maastricht Graduate School of Governance (MGSoG) I United Nations University - Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (UNU-MERIT) I September 2019 Dr. Katie Kuschminder | Talitha Dubow, Maastricht University/ UNU-MERIT • Prof. Dr. Ahmet İçduygu | Dr. Aysen Üstübici | Eda Kirişçioğlu, Koc Univeristy Prof. Dr. Godfried Engbersen, Erasmus University Rotterdam • Olga Mitrovic, Migration Consultant Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 List of abbreviations 3 Definitions 4 1. Introduction 6 2. The Western Balkans Route to Europe and the EU-Turkey Statement 7 2.1 Western Balkans Route 7 Status Quo in 2014 - Early 2015 | Opening of the Western Balkans Route | Closure of the Western Balkans Route 2.2 Overview of the EU-Turkey Statement and Policy Environment 9 Preparation Phase Building on the JAP | Entering into Force: Changes in Asylum in Greece | Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement: March 2016 - December 2018 2.3 Turkey Policy Environment and Conditions for Refugees in Turkey 15 2.4 Declining Numbers in Early 2016, What Role of the EU-Turkey Statement? 16 2.5 Summary 17 3. Conceptual Framework for Examining Refugees and Migrants’ Decision Making 18 3.1 Decision Making Processes in ‘Transit’ Spaces 18 3.2 Refugees and Migrants’ Decision Making Factors: An Exploratory Model 18 3.3 The Role of Policies in Refugees and Migrants’ Perceptions and Decision Making Processes 19 3.4 Migration Aspirations and Capabilities: Placing Decision Making in Context 21 3.5 Summary 21 4. Methodology 22 4.1 Selection of Case Studies 22 4.2 Timeline Methodology 22 4.3 Interview Methodology 23 4.4 Participant Overview 24 4.5 Limitations 24 4.6 Summary 25 5. -

Turkey COI Compilation 2020

Turkey: COI Compilation August 2020 BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Turkey: COI Compilation August 2020 The information in this report is up to date as of 30 April 2020, unless otherwise stated. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations................................................................................................................... -

Factoring Central Asia Into China's Afghanistan Policy

Journal of Eurasian Studies 5 (2014) 97–106 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Eurasian Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/euras Factoring Central Asia into China’s Afghanistan policy Ambrish Dhaka* School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, 587, D-Tower, Paschimabad, New Delhi 110067, India article info abstract Article history: China’s footprints in Afghanistan are vied by many, both, friends and rivals as it cautiously Received 19 June 2013 reveals its geostrategic goals. It would like to emulate the African and Central Asian success Accepted 29 September 2013 story in Afghanistan as well, which is not terra incognito. Afghanistan has been the fulcrum of geopolitical balance of power during the Cold war days. China’s Afghanistan policy (CAP) Keywords: is marked by its insecurities of terrorism, extremism and separatism in Xinjiang province. China It has heavily invested in procuring Central Asian energy resources. Both, the concerns go Afghanistan well in formulation of CAP. However, the presence of the US and Russia make the scenario Central Asia ‘ ’ Geopolitics competitive, where its Peaceful Rise may be contested. Besides, China sees South Asian Xinjiang Region as its new Geoeconomic Frontier. All these concerns get factored into CAP. It re- Geoeconomics mains to be seen what options partake in CAP, as China prepares for durable presence in Afghanistan in the long run. Copyright Ó 2013, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Hanyang University. Production and hosting by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction China to step in at this juncture given the fact that the losses western powers are suffering, which can only be If one looks at the map of Afghanistan, metaphorically compensated by China with a geopolitical bargain. -

Measuring Migration Aspirations and the Impact of Refugee Assistance in Turkey

Key Concepts in the Advancing Alternative Migration Governance Migration and Development: Measuring migration aspirations and the impact of refugee assistance in Turkey Deliverable 6.1 Ayşen Üstübici, Eda Kirişçioğlu, Ezgi Elçi June 2021 This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 822625. The content reflects only the authors’ views, and the European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains. Migration aspirations and the impact of refugee assistance in Turkey ADMIGOV Publication information You are free to share and cite this material if you include a proper reference. Suggested citation: Üstübici, A.; Kirişçioğlu, E.; Elçi, E. (2021) Migration and Development: Measuring migration aspirations and the impact of refugee assistance in Turkey, ADMIGOV Deliverable 6.1, Istanbul: Koç University. Available at http://admigov.eu You may not use this material for commercial purposes. Acknowledgments This paper has been written by Ayşen Üstübici, Eda Kirişçioğlu, and Ezgi Elçi, and peer-reviewed by Katie Kuschminder and Johannes Claes. All authors have equally contributed to the report. The views presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the institutions with which they are affiliated. The authors thank all survey respondents and interlocutors interviewed for this study for their time and insights. The authors are also grateful to Maryam Ekhtiari, Mustafa Hatip, Zahra Mohammadi, Hassan Reza Mirzaie, Mustafa Hatip, Morteza Salihi, Nerit Assad, and Lokman Osman for their help with translation and transcription of the interviews, to Alexander Burak Franklin for his help with editing and to the MiReKoc team, Prof. -

Decision Making on the Balkan Route and the EU-Turkey

Decision Making on the Balkan Route and the EU-Turkey Statement Maastricht Graduate School of Governance (MGSoG) I United Nations University - Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (UNU-MERIT) I September 2019 Dr. Katie Kuschminder | Talitha Dubow, Maastricht University/ UNU-MERIT • Prof. Dr. Ahmet İçduygu | Dr. Aysen Üstübici | Eda Kirişçioğlu, Koc Univeristy Prof. Dr. Godfried Engbersen, Erasmus University Rotterdam • Olga Mitrovic, Migration Consultant Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 List of abbreviations 3 Definitions 4 1. Introduction 6 2. The Western Balkans Route to Europe and the EU-Turkey Statement 7 2.1 Western Balkans Route 7 Status Quo in 2014 - Early 2015 | Opening of the Western Balkans Route | Closure of the Western Balkans Route 2.2 Overview of the EU-Turkey Statement and Policy Environment 9 Preparation Phase Building on the JAP | Entering into Force: Changes in Asylum in Greece | Implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement: March 2016 - December 2018 2.3 Turkey Policy Environment and Conditions for Refugees in Turkey 15 2.4 Declining Numbers in Early 2016, What Role of the EU-Turkey Statement? 16 2.5 Summary 17 3. Conceptual Framework for Examining Refugees and Migrants’ Decision Making 18 3.1 Decision Making Processes in ‘Transit’ Spaces 18 3.2 Refugees and Migrants’ Decision Making Factors: An Exploratory Model 18 3.3 The Role of Policies in Refugees and Migrants’ Perceptions and Decision Making Processes 19 3.4 Migration Aspirations and Capabilities: Placing Decision Making in Context 21 3.5 Summary 21 4. Methodology 22 4.1 Selection of Case Studies 22 4.2 Timeline Methodology 22 4.3 Interview Methodology 23 4.4 Participant Overview 24 4.5 Limitations 24 4.6 Summary 25 5. -

Social Sciences University of Ankara Institute of Social

SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ANKARA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MEDİNE DERYA CANPOLAT MIGRATION, INTEGRATION AND PERCEPTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF AFGHAN ASYLUM SEEKERS IN SIVAS MASTER THESIS JULY 2020 SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ANKARA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES MEDİNE DERYA CANPOLAT 170616009 MIGRATION, INTEGRATION AND PERCEPTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF AFGHAN ASYLUM SEEKERS IN SIVAS THESIS SUPERVISOR ASST. PROF. DR. K. ONUR UNUTULMAZ THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS ANKARA JULY 2020 STATEMENT ON ACADEMIC INTEGRITY I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all materials and results that are not original to this work. I declare that this thesis is written according to the writing rules of Social Sciences University of Ankara, Institute of Social Sciences. Name and Surname: Medine Derya CANPOLAT Signature: i ABSTRACT MIGRATION, INTEGRATION, AND PERCEPTIONS: A CASE STUDY OF AFGHAN ASYLUM SEEKERS IN SIVAS Medine Derya Canpolat MA International Relations Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. K. Onur Unutulmaz JULY 2020 The ultimate goal of this study is to analyze the local people’s perception of Afghan asylum seekers’ integration processes within the framework of qualitative and quantitative research methodologies in the case of Sivas city of Turkey. Since 1979, Afghans, who have fled from their countries due to invasions and civil war which caused political instabilities, economic insufficiencies, and concerns for the future, have represented a visible example of human mobility. In the literature, although there are various studies on Afghans related to security-oriented themes such as war, terror, and drug trade, studies focusing on local people’s perception regarding the integration processes of Afghan asylum seekers are unfortunately insufficient. -

Mutual Perceptions of Korean and Turkish Societies: Prospects for Development of Political, Economic and Cultural Relations

MUTUAL PERCEPTIONS OF KOREAN AND TURKISH SOCIETIES: PROSPECTS FOR DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL RELATIONS HYERIM CHOI JULY 2014 MUTUAL PERCEPTIONS OF KOREAN AND TURKISH SOCIETIES: PROSPECTS FOR DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL RELATIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY HYERIM CHOI IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MIDDLE EAST STUDIES JULY 2014 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha ALTUNIŞIK Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özlem TÜR Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Recep BOZTEMUR Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Recep BOZTEMUR (METU, HIST) Assoc. Prof. Dr. Erdoğan Yıldırım (METU, SOC) Assist. Prof. Dr. Çağatay Topal (METU, SOC) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Hyerim Choi Signature : iii ABSTRACT MUTUAL PERCEPTIONS OF KOREAN AND TURKISH SOCIETIES: PROSPECTS FOR DEVELOPMENT OF POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL RELATIONS Choi, Hyerim MSc., Department of Middle East Studies Supervisor : Prof. Dr. Recep BOZTEMUR July 2014, 273 pages This thesis analyzes mutual perceptions of the Turkish and Korean peoples about each other on the aspects of politics, military, economy, culture and education of the countries through in-depth interviews with Turkish and Korean people. -

Destination Unknown Afghans on the Move in Turkey

Destination Unknown Afghans on the move in Turkey MMC Middle East Research Report, June 2020 Front cover photo credit: Erdem Sahin/Epa-Efe/Ritzau Scanpix Afghan refugees and migrants on the move in Erzurum, Turkey. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Authors: Sema Buz, Fulya Memişoğlu, Hande Dönmez, independent and high-quality data, research, analysis and Simon Verduijn. and expertise on mixed migration. The MMC aims to increase understanding of mixed migration, to positively Research: TANDANS Data Science Consulting (Hande impact global and regional migration policies, to inform Dönmez, Tuna Kılınç, Benan Akyıldırım, Engin Kızılcan, evidence-based protection responses for people on Sema Buz, and Fulya Memişoğlu) and Mixed Migration the move and to stimulate forward thinking in public Centre Middle East (Simon Verduijn). and policy debates on mixed migration. The MMC’s overarching focus is on human rights and protection for Review: Suzan Yavuz, Nicoletta Gritta, Abdullah all people on the move. Mohammadi, Linnea Kessing, Rachel Bernu, Anthony Morland, Roberto Forin, and Bram Frouws. The MMC is part of and governed by the Danish Refugee Council (DRC). While its institutional link to DRC ensures Layout and design: Ali Mowafi. MMC’s work is grounded in operational reality, it acts as an independent source of data, research, analysis and Suggested citation: Mixed Migration Centre (2020), policy development on mixed migration for policy makers, Destination Unknown – Afghans on the move in Turkey. practitioners, journalists, and the broader humanitarian Available at www.mixedmigration.org sector. The position of the MMC does not necessarily reflect the position of DRC. We would like to particularly thank the respondents who were willing to share their time and insights The information and views set out in this report are those during interviews and focus groups, without which the of the MMC and do not necessarily reflect the official research would not have been possible. -

“INTEGRATION in LIMBO” Iraqi, Afghan, Maghrebi and Iranian Migrants in Istanbul

MiReKoc MIGRATION RESEARCH PROGRAM AT THE KOÇ UNIVERSITY __________________________________________________ MiReKoc Research Projects 2005-2006 “INTEGRATION IN LIMBO” Iraqi, Afghan, Maghrebi and Iranian Migrants in Istanbul A. Didem Danış Address: Galatasaray University, Sociology Dept. Ciragan Cad. No.36, Ortakoy 34357 Istanbul, Turkey Email: [email protected] Tel: +90. 212. 227 44 80 (x.405) Fax: +90. 212. 260 53 45 Koç University, Rumelifeneri Yolu 34450 Sarıyer Istanbul Turkey Tel: +90 212 338 1635 Fax: +90 212 338 1642 Webpage: www.mirekoc.com/mirekoc_eng.cgi E.mail: [email protected] Table of Content ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………… i List of tables …………………………………………………………………………………. iii List of photographs ………………………………………………………………………….. iv 1. INTRODUCTION (A. Didem Danış) …………………………...……..……………….. 1 1.1 Research Question …………………………………………………….......... 1 1.1.2 Terminology………………………………………………………………. 3 1.2 Design and Methodology ……..…………………………………………………… 3 1.3 Theoretical Significance ……………………………………………………………7 1.3.1 Incorporation of Migrants in Developing Countries ……………………… 7 1.3.2 Social Networks …………………………………………………………… 8 1.4 Changing Patterns of Migration Waves to Turkey………………………………...10 1.4.1 ‘Muhacirs’: Welcomed migrants of nation-state formation era…………... 10 1.4.2 Non-European Irregular Migrants in Istanbul …………………………... 11 1.5 Socio-Spatial and Economic Setting for Migrants’ Incorporation ………………. 16 1.5.1 Urban Scenery: Istanbul, home for migrants …………………………….. 16 1.5.2 A Vibrant Informal Economy: a pole of attraction for all migrants……… 18 1.5.3 Suitcase Trade ……………………………………………………………. 22 2. IRAQIS IN ISTANBUL: SEGMENTED INCORPORATION (A. Didem Danış) ...… 27 2.1 A Large But Invisible Migrant Group …………………………………………… 27 2.1.1 In between legal categories ………………………………………………. 29 2.1.2 A Short Chronology of Iraqi Migration ………………………………….. 33 2.2 Iraqi Kurds: Changing patterns in a long-standing migration wave …………….. -

Refuge & Hope in the Time of ISIS

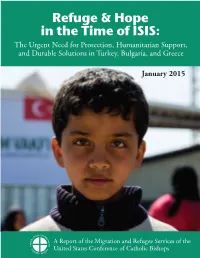

Refuge & Hope in the Time of ISIS: The Urgent Need for Protection, Humanitarian Support, and Durable Solutions in Turkey, Bulgaria, and Greece January 2015 A Report of the Migration and Refugee Services of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops i Designed by SYZYGY Media Copyright United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Washington, DC 2015 Cover Photo: Some 1.6 million children are fleeing from Syria and are seeking refuge in neighboring countries. Turkey generously hosts nearly half of those children. Photo by Russell Chapman. (http://russellchapman.wordpress.com/2014/12/14/syria-interesting-developments/) Table of Contents Letter from Bishop Eusebio Elizondo ................................................................................................................ 1 Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................2 I. The Refugee Crisis in Turkey ....................................................................................................................... 4 II. Bulgaria’s Asylum, Reception, and Integration Challenges ......................................................16 III. Greece’s Asylum, Reception, Detention, and Integration Challenges ...............................21 IV. Regional Challenges .......................................................................................................................................26 V. Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................................................31