Chapter I; INTRODUCTION to ICONOGRAPHY I. Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Single Footed Deities: Glimpses from Art and Literature

Single Footed Deities: Glimpses from Art and Literature Prachi Virag Sontakke1 1. Arya Mahila P.G. College, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India (Email: prachi.kushwaha @gmail.com) Received: 28 June 2015; Accepted: 03 August 2015; Revised: 10 September 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 608‐617 Abstract: Deities of religious pantheon are divine and hence they are attributed divine forms. The divinity of Gods is further glorified by conceiving their appearance as super natural. That is why we find Gods and Goddesses with multiple arms, heads and even limbs. These traits assert the power, superiority and divinity of deities before man. It is therefore very interesting to note that there is one such deity who is defined in literature and sculptural examples as having a single foot. Current paper is an attempt to understand the concept of emergence and development of this very single footed deity in India. In course of aforesaid trail, issues relating to antiquity of such a tradition, nomenclature of such deity, its identification with different Gods, respective iconography are also dealt with. Keywords: Ekpada, Antiquity, Art, Literature, Identification, Iconography, Chronology Introduction Iconography, though meant for art, is actually a science. Every aspect an icon is not only well defined but also well justified according to the iconographic principles laid down in the texts. When it came to sculpture making, artist’s freedom of portrayal and experimentation was rather limited. But this did not account for the lack of creativity and imagination in ancient Indian art. We have many examples where unrealistic depictions/forms were included in an icon to highlight the divine, supreme and all powerful aspect of deity and to make it different from ordinary humans. -

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

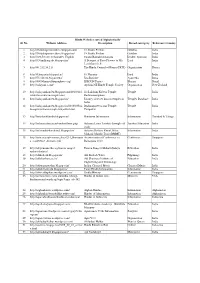

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

The Iconography of Surya

C1 V¥ /%. HIT 1711 1 1 1 l..IliVl JL mli If ■ 111 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF SUN GOD AND ASSOCIATED FEATURES ICONOGRAPH OF THE SUN- GOD AND ASSOCIATED FEATURES Iconography is the offspring of the ideas and craving of man to give a form to the formless! It is the concrete realization of the process of anthropomorphisation or humanization of the divinities. The worship of Surya, the light ' incarnate is perhaps the most ancient/ most impressive and the most popular one and realizing him in the iconic form is perhaps the most interesting one in the process. In the initial stage the sun-god was worshipped in his natural atmospheric form as is clear from all available sources. Different potteries, seals, sealing etc of the time represented his symbolically. But with the passage of time and with the gradual development of mankind, we notice the transformation of the Sun from its atmospheric and symbolic form to anthropomorphic figures. The available literary sources and the actual specimen of solar representations are unanimous on the fact that the anthropomorphic representation of the sun-god was preceded by the symbolic representation on coins and seals1. The non prevalence of the iconic tradition of the sun during the Rg. Vedic and later vedic phase is attached by the description of the Rg-Veda and the later - vedic texts1 • themselves. They do not give any reference to the image of the sun, on the other hand the Brahamanas3 give direct references to the symbolical depiction of the sun-god, not to his human form. The.Mahabharata and the Ramayana give4 us information about the complete anthropomorphisation of the Sun, but they contain no evidence for his iconic tradition. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Vaisnava Goddess As Plant: Tulasi in Text and Context John Carbone

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Vaisnava Goddess as Plant: Tulasi in Text and Context John Carbone Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES VAISNAVA GODDESS AS PLANT: TULASI IN TEXT AND CONTEXT By JOHN CARBONE A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of John Carbone defended on April 7, 2008. Kathleen M. Erndl Professor Directing Thesis Bryan Cuevas Committee Member Adam Gaiser Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For Irina and Joseph iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Kathy Neall for her help in editing this manuscript. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures .................................................................................... vi Abstract .......................................................................................... vii Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 1. Tulasī as the Plant Form of Lakṣmī................................................... 9 Śrī and Lakṣmī in the Vedas .......................................................... 9 Purāṇic Śrī and Lakṣmī.................................................................. Yakṣa, Yakṣī, and Śrī’s Iconography ............................................ -

ELEMENTS of HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All Books Are Subject to Recall After Two Weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library

' ^'•' .'': mMMMMMM^M^-.:^':^' ;'''}',l.;0^l!v."';'.V:'i.\~':;' ' ASIA LIBRARY ANNEX 2 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071128841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 071 28 841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A.^GOPINATHA RAO. M.A. SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part I. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 All Rights Reserved. KC- /\t^iS33 PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE, MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. DEDICATED WITH KIND PERMISSION To HIS HIGHNESS SIR RAMAVARMA. Sri Padmanabhadasa, Vanchipala, Kulasekhara Kiritapati, Manney Sultan Maharaja Raja Ramaraja Bahadur, Shatnsher Jang, G.C.S.I., G.C.I. E., MAHARAJA OF TRAVANCORE, Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, London, Fellow of the Geographical Society, London, Fellow of the Madras University, Officer de L' Instruction Publique. By HIS HIGHNESSS HUMBLE SERVANT THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. In bringing out the Second Volume of the Elements of Hindu Iconography, the author earnestly trusts that it will meet with the same favourable reception that was uniformly accorded to the first volume both by savants and the Press, for which he begs to take this opportunity of ten- dering his heart-felt thanks. No pains have of course been spared to make the present publication as informing and interesting as is possible in the case of the abstruse subject of Iconography. -

Indian Hindu Iconography of Twenty-Three Narasimha Images from Some Temples of Eastern Odisha Pjaee, 17 (5) (2020)

INDIAN HINDU ICONOGRAPHY OF TWENTY-THREE NARASIMHA IMAGES FROM SOME TEMPLES OF EASTERN ODISHA PJAEE, 17 (5) (2020) INDIAN HINDU ICONOGRAPHY OF TWENTY-THREE NARASIMHA IMAGES FROM SOME TEMPLES OF EASTERN ODISHA Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra Assistant Professor, Department of History, KISS, deemed to be University, Bhubaneswar, PIN-751024, Odisha, India Email: [email protected] Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra, Indian Hindu Iconography of Twenty-Three Narasimha Images from Some Temples of Eastern Odisha -- Palarch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology 17(5), 1767-1782. ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: Indian, Hindu, Iconography, Art, Narasimha, Images, Eastern Odisha ABSTRACT The study of extant Narasimha images of Eastern Odisha is one of the fascinating aspects of the Hindu Sculptural art of India. The region of Eastern Odisha is an important historical place of India. The worship of Lord Vishnu is prevalent in Eastern Odisha since the early medieval period. Narasimha, is the avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu who incarnates in the form of part lion and part man to destroy evil and end religious persecution and calamity on earth, thereby restoring Dharma. In the Hindu religion, Narasimha is the fourth avatarar of Lord Vishnu, the preserver god in the Hindu ‘Trimurti’ (Trinity), who appeared in ancient times to save the world from an arrogant demon figure. Narasimha or Nrusimha became the most popular god of the people of Odisha in the early medieval period. After the visit of various Vaishnava preachers to Odisha and establishment of different mathas, worship of Lord Vishnu in the form of Madhava (Madhavananda), Rama, Narasimha, Krushna, Narayana, Varaha, etc. -

Indian Serpent Lore Or the Nagas in Hindu Legend And

D.G.A. 79 9 INDIAN SERPENT-LOEE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART INDIAN SERPENT-LORE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART BY J. PH. A'OGEL, Ph.D., Profetsor of Sanskrit and Indian Archirology in /he Unircrsity of Leyden, Holland, ARTHUR PROBSTHAIN 41 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1926 cr," 1<A{. '. ,u -.Aw i f\0 <r/ 1^ . ^ S cf! .D.I2^09S< C- w ^ PRINTED BY STEPHEN AUSTIN & SONS, LTD., FORE STREET, HERTFORD. f V 0 TO MY FRIEND AND TEACHER, C. C. UHLENBECK, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED. PEEFACE TT is with grateful acknowledgment that I dedicate this volume to my friend and colleague. Professor C. C. Uhlenbeck, Ph.D., who, as my guru at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to introduce me to a knowledge of the mysterious Naga world as revealed in the archaic prose of the Paushyaparvan. In the summer of the year 1901 a visit to the Kulu valley brought me face to face with people who still pay reverence to those very serpent-demons known from early Indian literature. In the course of my subsequent wanderings through the Western Himalayas, which in their remote valleys have preserved so many ancient beliefs and customs, I had ample opportunity for collecting information regarding the worship of the Nagas, as it survives up to the present day. Other nations have known or still practise this form of animal worship. But it would be difficult to quote another instance in which it takes such a prominent place in literature folk-lore, and art, as it does in India. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The "Dhyana Collections" and Their Significance for Hindu Iconography

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 40, No. 2, March 1992 The "Dhyana Collections" and Their Significance for Hindu Iconography Gudrun BUHNEMANN The purposeof this paper is to draw attentionto a rather neglected type of literaturehaving few edited specimens.1) Texts of this genre are cata- logedunder titles such as "Dhyanamala", "Dhyanaslokah" or "Dhyanasam- graha".2) As the titles indicate, these texts are collections of dhyana-s. The word dhyana connotes a description of the deity's appearance, obvi- ously intendedas an aid for his/her visualization. The translation "medita- tion" for dhyanawith its complexand modern associations is better to avoidhere as it is misleading. A typical dhyana collection systematically lists the characteristics of di- fferent deities, beginningwith the deity considered most important and his/her forms or emanations and then going on to deities of lesser importa- nce. In this way descriptions of the complete Hindu pantheon are provided. Localdeities of the "LittleTradition" are also included and connected with deitiesof the "Great Tradition." The choice and the sequence of the deities described allow speculations about the region and the religious milieu in whichthe texts originated. Usually the collections use descriptions found in Puranas, Tantric texts or earlier dhyana collectionsand are arranged by anonymous compilers who do not indicate their sources. Sometimes there are referencesto certain Tantric traditions (amnaya) to which a form of a deity belongs.The collections often contain verses written in kavya metres. The tendencyto use only one verse for one deity also favours the use of the longermetres. Several descriptions of one deity collected from different sources may be given sequentially. -

Vaikhanasa Agamam V1

1. Sincere thanks to "srI nrusimha seva rasikan" Oppiliappan Koil SrImAn VaradAccAri SaThakOpan swami, the Editor-in-Chief of SrIhayagrIvan eBooks series for kindly hosting this title under his series. I am very much indebted for the support and encouragement from SrImAn SaThakOpan Swamin!! 2. Thanks are also due to The Secretary, Vikhanas Trust, Tirumala Hills, Sriman G. Prabhakaracharyulu, for encouraging me to do this likhita kaimkaryam to the Astika Community on the Net. 3. Sincere thanks are also due to www.tirupatitimes.com, www.vaikhanasa.com, sadagopan.org www.srivaishnavam.com, Nedumtheru SrI Mukund Srinivasan, SrI B.Senthil, SrI T.Raghuveeradayal and rAmanuja dAsargal at www.pbase.com/svami for their loving contributions of images to this eBook 4. Last but not the least, thanks are also due to www.srivari.com for providing the details of the different VaikhAnasa Aagama kshetrams covered in the appendices. NOTE: The primary author, Archakam SrI Ramakrishna Deekshitulu, Archaka, Srivari Temple, Tirumala Hills, can be contacted for discussions about the topics related to this eBook by any of the AstikAs on the Net by sending email to [email protected] C O N T E N T S prArthanA slokam 1 Introduction 3 VaikhAnasam 4 VaikhAnsas and SrI VikhAnasa Maharishi 16 VaikhAnasa ideology 26 VaikhAnasa Kalpa sUtra 29 SrI VishNu - Supreme godhead of VaikhAnasas 33 sadagopan.org Atma sUktam 39 SrI VaikhAnasa Bhagavad SAstram 49 VaikhAnasa Literature 61 Divya desams following VaikhAnasa Aagamam 80 nigamanam 82 Appendices 83 Appendix 1 -