Single Footed Deities: Glimpses from Art and Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday Hindu Story

Lord Brahma Brahma is the creator of the universe and all knowledge. He is the first god in the Hindu Trimurti (three gods who are responsible for the creation, preservation and destruction of the world). Brahma grew inside a lotus from the navel of a sleeping Vishnu. He has 4 heads and has the goddess Saraswati as a companion. Brahma is sometimes depicted with a beard. Lord Vishnu Vishnu is the Hindu god who preserves the universe and people. He is the second god in the Hindu Trimurti. Hindus believe that he has saved his followers by appearing to them in other forms. Vishnu has four arms to represent the four corners of the world. Lord Shiva Shiva is the destroyer of the universe so that new life can come again. He restores the balance between good and evil. He is the third god in the Hindu Trimurti. Ganesh Ganesh is the elephant-headed god and the Lord of all living things. He is the god who helps people overcome their problems by granting them wisdom and strength. It is said that the god Shiva cut off his original head and restored him to life by giving him the head of an elephant. Lakshmi Lakshmi is the wife of Vishnu and travels on a lotus flower. She is the goddess of wealth and success. Sita Sita is actually an incarnation of the goddess Lakshmi. She is a beautiful, loyal wife and a role model for Hindu women. Rama Rama is the ‘perfect’ avatar of Vishnu. He is a symbol of chivalry and virtue. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

Hinduism Summary Key Words

Hinduism Summary Key Words Hindu Someone who follows Hinduism. Hinduism is the oldest of the world’s religions. It is now practised all over the world but originated in South East Asia. It is a mix of different Brahman Hindus recognise one God, Brahman. The other Gods of Hinduism are different aspects of Brahman (The universal supreme God) beliefs, cultures and traditions dating back over 4000 years. Hindus Vishnu Hindu god who protects the universe. recognise one God, Brahman. The gods of Hinduism are different aspects Brahma Hindu god of creation. of Brahman. The main three aspects (Trimurti) are Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva. The three great goddesses (Tridevi) are Saraswati, Lakshmi and Shiva Hindu god of destruction and regeneration Shakti. Hindus can pray to different gods and goddesses for help with Trimurti The three aspects of the universal supreme God. (Vishnu, Brahma and Shiva) All of which can be represented in male or female forms. different needs. There are over 1.1 billion Hindus in the world today. mandir A special place for Hindus to worship. Avatars of the three main aspects of Brahman puja Act of worship for Hindus. murtis Special statues or images of Hindu gods and goddesses. Brahma Shiva Vishnu shrine A holy place to pray. (the creator) (the protector) (the destroyer of evil) Shruti Hindu holy scriptures which contain the four Vedas. Smriti Hindu holy scriptures which contain legends, myths and history. Vedas Ancient Hindu text. Avatar In Hinduism, this usually refers to an incarnation of God or His aspects, either as a man or even an animal or some mythical creature. -

Painting Reckoner Session: 2020-21

SALWAN PUBLIC SCHOOL MAYUR VIHAR PAINTING RECKONER SESSION: 2020-21 NAME: CLASS: XI SECTION: Preface The course in Painting at Senior Secondary stage as an elective subject is aimed to develop aesthetic sense of the students through the understanding of various important well known aspects and modes of visual art expression in India’s rich cultural heritage from the period of Indus valley to the present time. It also encompasses practical exercises in drawing and painting to develop their mental faculties of observation, imagination, creation and physical skills required for its expressions. The Ready Reckoner for Class XI has been prepared in conformity with the National Curriculum Framework and latest CBSE syllabus and pattern. We believe, this text will make apparent the content and scope of the Subject and provide the foundation for further learning. With necessary assignments within each part, chapters are devoted to the subtopics, and the assignments are designed according to the lower and higher order thinking skills. Chapter- opening summary is intended to capture the reader's interest in preparation for the subject matter that follows. In short, every effort has been made to gain and retain student attention— the essential first step in the learning process. INDEX 1. Objectives 2. Important Art Terminologies 3. Syllabus and Division of Marks 4. Prehistoric Rock Paintings 5. Indus Valley Civilization 6. Mauryan Period 7. Art of Ajanta 8. Temple Architecture 9. Bronze Sculptures 10. Some Aspects of Indo-Islamic Architecture 11. Sample Papers Objectives A) Theory (History of Indian Art) The objective of including the history of Indian Art for the students is to familiarize them with the various styles and modes of art expressions from different parts of India. -

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

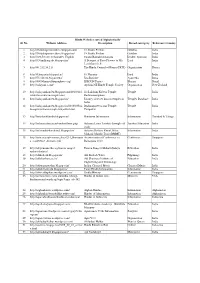

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Marks Dissertation Post-Defense

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Playfighting: Encountering Aviddhakarṇa and Bhāvivikta in Śāntarakṣita's Tattvasaṃgraha and Kamalaśīla's Pañjikā Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9wj6z2j3 Author Marks, James Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Playfighting: Encountering Aviddhakarṇa and Bhāvivikta in Śāntarakṣita's Tattvasaṃgraha and Kamalaśīla's Pañjikā By James Michael Marks A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Buddhist Studies In the Graduate Division Of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alexander von Rospatt, Chair Professor Robert H. Sharf Professor Mark Csikszentmihalyi Professor Robert P. Goldman Professor Isabelle Ratié Spring 2019 Abstract Playfighting: Encountering Aviddhakarṇa and Bhāvivikta in Śāntarakṣita's Tattvasaṃgraha and Kamalaśīla's Pañjikā by James Michael Marks Doctor of Philosophy in Buddhist Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Alexander von Rospatt, Chair The present study collects, translates, and analyzes the surviving fragments of two lost Naiyāyika authors, Aviddhakarṇa and Bhāvivikta, principally as they have been preserved in the works of the eighth-century Buddhist philosophers Śāntarakṣita and Kamalaśīla. (The present study argues, without coming to a definite conclusion as yet, that there is strong evidence Aviddhakarṇa and Bhāvivikta -

The Iconography of Surya

C1 V¥ /%. HIT 1711 1 1 1 l..IliVl JL mli If ■ 111 THE ICONOGRAPHY OF SUN GOD AND ASSOCIATED FEATURES ICONOGRAPH OF THE SUN- GOD AND ASSOCIATED FEATURES Iconography is the offspring of the ideas and craving of man to give a form to the formless! It is the concrete realization of the process of anthropomorphisation or humanization of the divinities. The worship of Surya, the light ' incarnate is perhaps the most ancient/ most impressive and the most popular one and realizing him in the iconic form is perhaps the most interesting one in the process. In the initial stage the sun-god was worshipped in his natural atmospheric form as is clear from all available sources. Different potteries, seals, sealing etc of the time represented his symbolically. But with the passage of time and with the gradual development of mankind, we notice the transformation of the Sun from its atmospheric and symbolic form to anthropomorphic figures. The available literary sources and the actual specimen of solar representations are unanimous on the fact that the anthropomorphic representation of the sun-god was preceded by the symbolic representation on coins and seals1. The non prevalence of the iconic tradition of the sun during the Rg. Vedic and later vedic phase is attached by the description of the Rg-Veda and the later - vedic texts1 • themselves. They do not give any reference to the image of the sun, on the other hand the Brahamanas3 give direct references to the symbolical depiction of the sun-god, not to his human form. The.Mahabharata and the Ramayana give4 us information about the complete anthropomorphisation of the Sun, but they contain no evidence for his iconic tradition. -

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY (Accredited with ‘A’ Grade by NAAC) KARAIKUDI – 630 003 TAMILNADU

ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY (Accredited with ‘A’ Grade by NAAC) KARAIKUDI – 630 003 TAMILNADU DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION (Recognized by Distance Education Council (DEC), New Delhi) POST GRADUATE / P.G.DIPLOMA /CERTIFICIATE COURSE PROGRAMMES REGULATIONS AND SYLLABI Copy Right Reserved For Private use only Copy Right Reserved For Private use only ALAGAPPA UNIVERSITY, KARAIKUDI DIRECTORATE OF DISTANCE EDUCATION REGULATIONS AND SYLLABI P.G. / P.G. DIPLOMA Sl.No. Course Page No. 1 M.Com 3-14 2 M.Com(F&C) 15-25 3 M.A.(Tamil) 26-33 4 M.A.(English) 34-42 5 M.A.(History) 43-55 6 M.A.(Education) 56-74 7 M.A.(Sociology) 75-87 8 M.A.(Personnel Management & Industrial 88-98 Relations) 9 M.A.(Master of Journalism and Mass 99-109 Communication) 10 M.A.(Child Care & Education) 110-121 11 M.Sc(Mathematics) 122-132 12 M.Sc(Information Technology) 133-156 13 M.Sc(Computer Science) 157-173 14 Master of Library and Information Science 174 -182 (MLIS) (One year) 1 14 M.Sc(Physics) 183 - 203 15 M.Sc(Chemistry) 204 – 227 16 M.Sc(Botany with Specialization in Plant Bio- 228 – 241 Technology) 17 M.Sc(Zoology) 242 - 243 18 P.G.Dip. in (Personnel Management & 263 – 268 Industrial Relations) 19 P.G.Dip. in (Business Management) 269 – 275 20 P.G.Dip. in (Hospital Administration) 276 – 282 21 P.G.Dip. in (Sports Management) 283 – 287 22 P.G.Dip. in (Human Resource Management) 288 - 293 23 P.G.Dip. in (Yoga Education) 294 – 351 2 Course : M.Com. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Religious Studies Paper

Name Tutor RPE Class RPE Teacher Homework Your homework is to revise the key knowledge for this unit. • You will have a banded assessment and a knowledge quiz at the HWK Completed: Score: end of this unit. 1 2 • Your grade and score will reflect how well you have revised during the term. 3 4 • This booklet contains fortnightly revision activities that you must 5 complete to prepare. 6 7 • This booklet must be brought in for your teacher to see on the 8 homework due date. • All answers are on the knowledge organiser. Overall Score: • The activities will be marked in class on the homework due date. Overall Percentage: • Atman: The eternal spirit inside • Hinduism: Gets its name from • Sanskrit: Ancient Indian every living being, part of the the River Indus in India where language many of the scripture ultimate being. Hinduism began. is written in. • Aum: A sacred sound that is • Hindu: A follower of the religion • Shaiva: A Hindu who believes important to Hindus which they Hinduism. that Shiva is the supreme God. chant. • Karma: That all actions have • Shiva: The destroyer and re- • Avatar: When a god takes the consequences. Good actions = creator. form of an animal or a human good consequences. Bad • Supreme: The best or greatest. and comes to earth to fight evil actions = bad consequences. • Symbol: An image that and establish peace and • Moksha: Where a Hindu is freed expresses religious ideas. harmony. from samsara and back with • Trimurti: A term for the three • Brahma: The creator. Brahman. main Hindu gods Brahma, • Brahman: Many Hindus believe • Monotheist: Someone who Vishnu and Shiva.