Persian Gulf States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arthurs New Puppy Free

FREE ARTHURS NEW PUPPY PDF Marc Brown | 32 pages | 03 Jul 2008 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316109215 | English | New York, United States Arthur's New Puppy (book) | Arthur Wiki | Fandom Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Arthur's new puppy causes problems when it tears the living room apart, wets on everything, and refuses to wear a leash. Arthur is thrilled when he gets a new puppy. He's had a lot of experience with pets Arthurs New Puppy he knows they're as much work as they are fun. Even so, when Pal tears the living room apart, wets on everything, and refuses to wear his leash, Arthur gets worried. His parents are unhappy with Pal's behavior and even D. What if Arthur can't control Pal-and Pal gets sent away to live on a farm? Readers of all ages will laugh out loud as they follow Pal's progress from mischievious scamp to dog show material under the loving guidance of his owner, Arthur. Get A Copy. Paperback32 pages. More Details Original Title. Arthur Adventure Series. Other Arthurs New Puppy 1. Friend Reviews. To Arthurs New Puppy what your friends thought of this Arthurs New Puppy, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Arthur's New Puppyplease sign up. What puppy did at this Arthur's new puppy? What color Arthurs New Puppy his puppy. -

Exclusion and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-15-2017 Crystallizing a Discourse of "Khalijiness": Exclusion and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States Khaled A. Abdulkarim University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Abdulkarim, Khaled A., "Crystallizing a Discourse of "Khalijiness": Exclusion and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States" 15 May 2017. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/211. A senior thesis submitted to the Huntsman Program in Business and International Studies, the University of Pennsylvania, in partial fulfillment of the program degree requirements. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Crystallizing a Discourse of "Khalijiness": Exclusion and Citizenship in the Arab Gulf States Abstract For many of the Arab Gulf countries, non-national populations constitute the majority of the population, with the discrepancy between the size of the national and non-national populations continuing to grow. It is in this context that the role played by these non-national populations becomes critically important. In my paper, I argue that exclusion of non-national populations from state-sponsored national identities, as manifest through citizenship rights, plays a pivotal role in fostering imagined national identities and communities among the local Arab Gulf citizens. The study considers two cases in particular: the bidoon (stateless) of Kuwait and middle-class Indian migrants in Dubai. -

Ending Injustice in Our Fields and Dairies: New York State Should Extend Basic Labor Protections to Farmworkers

POLICY BRIEF | MAY 2019 Ending Injustice in Our Fields and Dairies: New York State Should Extend Basic Labor Protections to Farmworkers In 1937, New York State lawmakers passed fundamental labor protections for the state’s workers. But just as Congress had done in the landmark federal labor law enacted two years earlier, New York lawmakers excluded farmwork and other industries disproportionately employing workers of color from these protections. In the eight decades since, farmworkers have been paid low wages for onerous work, suffered poor living conditions, and been exposed to wage theft, physical injury, trafficking, and harassment. Since the 1990s, lawmakers in Albany have promised to address this shortcoming, and yet these unfair exclusions from basic legal protections persist. Often working in rural isolation, for employers who control virtually every aspect of their lives, the men and women who produce our sustenance cannot depend upon basic labor laws, and yet they are also constrained from banding together to improve their conditions. We are past due to end the discrimination in New York’s fields and dairies, and to extend collective bargaining rights and other baseline labor protections to farmworkers. To Farmworkers, Promises Made and Promises Broken Time and time again, agricultural workers laboring in one of the lowest-paid and most dangerous occupations in the United States have been told by policymakers that they don’t matter. As a result of legislative compromises in the drafting of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) -

Interview with Dayton S. Mak

Library of Congress Interview with Dayton S. Mak The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project DAYTON S. MAK Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: August 9, 1989 Copyright 2010 ADST Q: Dayton, when and where were you born? MAK: I was born in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, July 10, 1917. Q: Let's talk about the family, let's go on the Mak side. What do you know about them? MAK: The Mak original name was three-barrel Mak van Waay, which in Dutch would be Mak fon vei [pronounces in Dutch]. They were from Dordrecht, the Netherlands. The family had an antique showroom there, an auction house a bit like Sotheby's. Q: ...in... MAK: In Dordrecht. That was the Mak van Waay family. They then moved to Amsterdam. At the same time, anther part of the family, a son, I believe, wanted to establish a Mak van Waay firm in Dordrecht itself. According to Dutch law, they couldn't do that. There could only be one firm Mak van Waay, so they opened the Firma Mak in Dordrecht. The Firma Mak still exists, and the big building remains on the tour of the old city of Dordrecht. The Mak van Waay part, of which I'm a member, stayed in Amsterdam until about 15 years ago, when the last Mak van Waay died. He had no children. So, the Mak van Waay in Interview with Dayton S. Mak http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000739 Library of Congress Holland effectively died out. -

The Foreign Policy of the Arab Gulf Monarchies from 1971 to 1990

The Foreign Policy of the Arab Gulf Monarchies from 1971 to 1990 Submitted by René Rieger to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Politics in June 2013 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………… ………… 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation provides a comparative analysis of the foreign policies of the Arab Gulf monarchies during the period of 1971 to 1990, as examined through two case studies: (1) the Arab Gulf monarchies’ relations with Iran and Iraq and (2) the six states’ positions in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The dissertation argues that, in formulating their policies towards Iran and Iraq, the Arab Gulf monarchies aspired to realize four main objectives: external security and territorial integrity; domestic and regime stability; economic prosperity; and the attainment of a stable subregional balance of power without the emergence of Iran or Iraq as Gulf hegemon. Over the largest part of the period under review, the Arab Gulf monarchies managed to offset threats to these basic interests emanating from Iran and Iraq by alternately appeasing and balancing the source of the threat. The analysis reveals that the Arab Gulf monarchies’ individual bilateral relations with Iran and Iraq underwent considerable change over time and, particularly following the Iranian Revolution, displayed significant differences in comparison to one another. -

The 17Th International Colloquium on Amphipoda

Biodiversity Journal, 2017, 8 (2): 391–394 MONOGRAPH The 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda Sabrina Lo Brutto1,2,*, Eugenia Schimmenti1 & Davide Iaciofano1 1Dept. STEBICEF, Section of Animal Biology, via Archirafi 18, Palermo, University of Palermo, Italy 2Museum of Zoology “Doderlein”, SIMUA, via Archirafi 16, University of Palermo, Italy *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] th th ABSTRACT The 17 International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17 ICA) has been organized by the University of Palermo (Sicily, Italy), and took place in Trapani, 4-7 September 2017. All the contributions have been published in the present monograph and include a wide range of topics. KEY WORDS International Colloquium on Amphipoda; ICA; Amphipoda. Received 30.04.2017; accepted 31.05.2017; printed 30.06.2017 Proceedings of the 17th International Colloquium on Amphipoda (17th ICA), September 4th-7th 2017, Trapani (Italy) The first International Colloquium on Amphi- Poland, Turkey, Norway, Brazil and Canada within poda was held in Verona in 1969, as a simple meet- the Scientific Committee: ing of specialists interested in the Systematics of Sabrina Lo Brutto (Coordinator) - University of Gammarus and Niphargus. Palermo, Italy Now, after 48 years, the Colloquium reached the Elvira De Matthaeis - University La Sapienza, 17th edition, held at the “Polo Territoriale della Italy Provincia di Trapani”, a site of the University of Felicita Scapini - University of Firenze, Italy Palermo, in Italy; and for the second time in Sicily Alberto Ugolini - University of Firenze, Italy (Lo Brutto et al., 2013). Maria Beatrice Scipione - Stazione Zoologica The Organizing and Scientific Committees were Anton Dohrn, Italy composed by people from different countries. -

Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle

Kunapipi Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 15 1992 A Female Houdini: Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle John Thieme Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Thieme, John, A Female Houdini: Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle, Kunapipi, 14(1), 1992. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol14/iss1/15 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A Female Houdini: Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle Abstract Popular discourses are ubiquitous in the writing of Margaret Atwood. Her novels, poetry and critical writing constantly foreground ways in which notions of gender identity, and of cultural identity more generally, have been shaped by media and other popular representations. References to Hollywood and television rub shoulders with allusions to magazines, fairy tale, popular song and a host of other forms responsible for women's socialization and female mythologies: these include the Persephone2 and Triple Goddess3 myths, popular religious discourse, advertising language and iconography and the stereotypical norms inculcated in girls by such institutions as Brownies and Home Economics classes.4 This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol14/iss1/15 AFemale Houdini: Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle 71 JOHN THIEME A Female Houdini: Popular Culture in Margaret Atwood's Lady Oracle There are whole magazines with not much in them but the word love, you can rub it all over your body and you can cook with it too.' 1 (Margaret Atwood, 'Variations on the Word Love' ) Popular discourses are ubiquitous in the writing of Margaret Atwood. -

Trade and Cultural Contacts Between Northern and Southern Persian Gulf During Parthians and Sasanians: a Study Based on Pottery from Qeshm Island

Intl. J. Humanities (2011) Vol. 18 (2): (89-115) Trade and Cultural Contacts between Northern and Southern Persian Gulf during Parthians and Sasanians: A Study Based on Pottery from Qeshm Island Alireza Hojabri-Nobari 1, Alireza Khosrowzadeh 2, Seyed Mehdi Mousavi Kouhpar 3, Hamed Vahdatinasab 4 Received:21/9/2011 Accepted:3/1/2011 Abstract The first season of survey at Qeshm, carried out during the winter of 2006, resulted in the identification of nine sites from the Parthian and Sasanian periods. The surface pottery from these sites suggests their trade and cultural relations with contemporary sites in the southern Persian Gulf and other areas. For instance, the Parthian and Sasanian glazed types in Qeshm Island are closely related materials found from Khuzestan as well as northern and southern coasts of the Persian Gulf, including ed-Dur, Suhar, Kush, Failaka and Qalat Bahrain. Parthian painted ware reveals close similarities to monochrome and bichrome painted pottery of southeastern Iran, Oman coasts and the southern Persian Gulf, specifically ed-Dur, Suhar, Kush and Tel-i-Abrak. The so-called Indian Red Polished Ware is the other diagnostic type widespread in the northern and southern coasts of the Persian Gulf from the middle Parthian up to the Downloaded from eijh.modares.ac.ir at 11:47 IRDT on Monday August 31st 2020 early Islamic period. The material was being widely produced in the Indian region (Gujarat) and Indus, and exported to different places around the Persian Gulf. The Coarse Black Ware ( ceramic noir epaise ) with decorative raised bands recorded in Qeshm compares with coarse-black material from the southern Persian Gulf, also occurring at sites such as ed-Dur and Abu Dhabi Islands. -

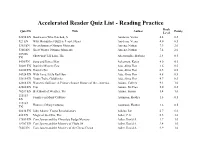

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

Equinor Makes It Work Globally with Synergi

SAFER, SMARTER, GREENER © xxx Equinor © Statoil - Hald Pettersen © Statoil DIGITAL SOLUTIONS – SYNERGI™ LIFE EQUINOR MAKES IT WORK GLOBALLY WITH SYNERGI Customer story – Equinor Operating in some 40 countries, Norwegian oil company Equinor has ambitious goals for further worldwide growth. Synergi Life is the group’s risk management system wherever it goes, regardless of geography and language. Equinor has always had an international orientation, but the department for analysis, monitoring and support in the group’s character of its operations has been changing. Much respected International Exploration & Production business area, and Synergi for its deepwater drilling expertise, the group has primarily been Life is part of his everyday life. a partner to other operators when it is outside the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). “We have no exceptions in Equinor – everyone uses Synergi Life in every country,” Mr Martinsen explains. “If they don’t have PCs, Over the last few years, however, it has been acquiring operator- we must accept that they need to use paper forms. And if they ships in various countries, including the US Gulf of Mexico, Brazil can’t read and write, we’ll have to solve that as well.” and Canada. The overall quality, health, safety and environmental (QHSE) strategy thereby becomes Equinor’s responsibility and “That’s because a key criterion for success in the HSE area is a allows it to explore some new challenges. country manager who’s dedicated to HSE work and who realizes the importance of good quality reports,” he says. “One particular “We’ve been a big Synergi Life user since the beginning, and enthusiast in Iran has now been nominated for our internal HSE we get a lot of good output,” says Arne M. -

EBCS AR Titles

EBCS AR Titles QUIZNO TITLE 41025EN The 100th Day of School 35821EN 100th Day Worries 661EN The 18th EmerGency 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Sea 11592EN 2095 8001EN 50 Below Zero 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins 413EN The 89th Kitten 80599EN A-10 Thunderbolt II 16201EN A...B...Sea (Crabapples) 67750EN Abe Lincoln Goes to WashinGton 1837-1865 101EN Abel's Island 9751EN Abiyoyo 86635EN The Abominable Snowman Doesn't Roast Marshmallows 13551EN Abraham Lincoln 866EN Abraham Lincoln 118278EN Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War 17651EN The Absent Author 21662EN The Absent-Minded Toad 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How I Visited Yellowstone... 17501EN Abuela 15175EN Abyssinian Cats (Checkerboard) 6001EN Ace: The Very Important PiG 35608EN The Acrobat and the AnGel 105906EN Across the Blue Pacific: A World War II Story 7201EN Across the Stream 1EN Adam of the Road 301EN Addie Across the Prairie 6101EN Addie Meets Max 13851EN Adios, Anna 135470EN Adrian Peterson 128373EN Adventure AccordinG to Humphrey 451EN The Adventures of Ali Baba Bernstein 20251EN The Adventures of Captain Underpants 138969EN The Adventures of Nanny PiGGins 401EN The Adventures of Ratman 64111EN The Adventures of Super Diaper Baby 71944EN AfGhanistan (Countries in the News) 71813EN Africa 70797EN Africa (The Atlas of the Seven Continents) 13552EN African-American Holidays EBCS AR Titles 13001EN African Buffalo (African Animals Discovery) 15401EN African Elephants (Early Bird Nature) 14651EN Afternoon on the Amazon 83309EN Air: A Resource Our World Depends -

Download Tour

Qeshm Island Tour Tour Destinations: Tehran to Tehran Duration: 5Days Tour styles: Style Nature Adventurous Cultural Code: PIQI Tour route: Tehran The Qeshm Island Tehran Tailor made Tour highlights The exotic Chahkooh Valley, Lenj boat workshop (UNESCO heritage), Hengam Island, scenic beaches What you need to know about this tour Qeshm Island is a newly discovered destination in southern Iran, attracting the travelers who seek untouched beaches, unspoiled culture and mild weather during winter, when everywhere else is covered with snow. Qeshm and other islands around it are fantastic places for relaxing, water sports and meeting locals who live in unknown villages. PacktoIran has designed “Qeshm Island Adventure” as a tour for the nature lovers who are seeking new Island experience. What is Included 4 nights accommodation at ecolodge English speaking guide Private vehicle Airport transfers Tour accommodations: Nights stay in Ecolodge Tour Meals: 4 Breakfasts, 1 Lunch, 2 Dinner Day 1: Tehran-Qeshm Welcome to Iran. This tour will start from Tehran, the capital of Iran. Considering your arrival time, you can visit the top attractions of Tehran, like the UNESCO listed Golestan Palace or the Iran National Museum. In the afternoon you’ll be transferred to Mehrabad Airport for your domestic flight to the Qeshm Island. Your leader will meet you at the airport and you will head to the eco-lodge at one of the villages of Qeshm Island, where you can get relaxed and unattached from city hustle for a couple of days. This afternoon you will take a walk by an untouched beach and have a local homemade meal as welcome dinner.