Tracking the Transmediality of Red Nose Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comic Relief: Multi-Cloud, Multi-Foundation, 400 Real-Time Donations Per Second, Zero Downtime, 100% Success

Comic Relief: Multi-cloud, multi-foundation, 400 real-time donations per second, zero downtime, 100% success Over the past 30 years, Comic Relief [http://www.comicrelief.com/] has raised over £1 billion for good causes around the world and in the UK. Through their two campaigns Red Nose Day [www.rednoseday.com] and Sport Relief [http://www.sportrelief.com/], they used the money donated by the great British public to make their vision a reality: a just world, free from poverty. Founded in 1985 by comedy scriptwriter Richard Curtis and comedian Lenny Henry in response to famine in Ethiopia, every year Comic Relief has grown in size and influence. In its first telethon in 1998 it raised £76,610. In 2015, it raised £99,418,831. Every two years, Comic Relief’s Red Nose Day takes over primetime Friday night BBC TV for seven hours. The telethon is responsible for the majority of Comic Relief’s annual fundraising, attracting a large audience who donate money via the website or a network of 14,000 call centre operators across 120 call centres who donate their time for free. “With an increasing number of donations to Comic Relief being taken online, it is critical we have 100% confidence in our donations platform. Armakuni provides us with that confidence.” Derek Gannon, COO, Comic Relief The old donations platform The directors appreciated that the existing platform was nearing its end of life and a new platform was needed - when such a large percentage of your annual money is made in about 7 hours, you really want to know the thing is not going to fail. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Lost Pigs and Broken Genes: The search for causes of embryonic loss in the pig and the assembly of a more contiguous reference genome Amanda Warr A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh 2019 Division of Genetics and Genomics, The Roslin Institute and Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has been carried out, and the thesis composed, by the candidate Amanda Warr. Contributions by other individuals have been indicated throughout the thesis. These include contributions from other authors and influences of peer reviewers on manuscripts as part of the first chapter, the second chapter, and the fifth chapter. Parts of the wet lab methods including DNA extractions and Illumina sequencing were carried out by, or assistance was provided by, other researchers and this too has been indicated throughout the thesis. -

Britain's Got Talent C - X-Factor D - Idol

JLS Test sprawdzający Twoją wiedzę o brytyjskim boysbandzie Jack the Lad Swing (JLS) :D Poziom trudności: Średni 1. W jakim show wzięło udział JLS w 2008 r. ? A - Must be the music B - Britain's got talent C - X-Factor D - Idol 2. Jaką nazwę nosił zespół przed obecną? A - UFO B - JSL C - FDE D - zawsze było JLS 3. Jak mają na imię członkowie zespołu? A - Aston, Marvin, William, Jonathan B - Oritse, Aston, Jonathan, Marvin C - Richard, James, Aston, Oritse D - Alex, Harry, Marvin, Aston 4. Jak nazywa się żona Marvina Humes'a ? A - on nie ma żony B - Frankie Standford C - Rochelle Wiseman D - Rihanna 5. Z jakiego miasta pochodzi Aston Merrygold? A - Londyn B - Sheffield C - Glasgow D - Peterborough Copyright © 1995-2021 Wirtualna Polska 6. Kto był mentorem JLS w show muzycznym ? A - Simon Cowell B - Cheryl Cole C - Louis Walsh D - Kylie Minogue 7. Ile płyt wydało dotychczas JLS? A - 3 B - 2 C - 1 D - 4 8. Jak nazywała się ostatnia trasa koncertowa JLS, obejmująca całe UK ? A - Only Tonight Theatre tour B - The 4th dimensions C - Summer tour D - Sport Relief tour 9. Jaki tytuł nosi piosenka, którą JLS nagrało dla Sport Relief 2012? A - Do you feel what I feel B - Proud C - She makes me wanna D - Take a chance on me 10. Jaką piosenkę Michaela Jacksona solowo wykonał JB Gill podczas Only Tonight tour ? A - I want you back B - Thiller C - Don't stop till you get enough D - Will you be there 11. W którym roku urodził się najmłodszy członek zespołu? A - 1990 B - 1988 C - 1993 Copyright © 1995-2021 Wirtualna Polska D - 1986 12. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature

Studies in English, New Series Volume 4 Article 39 1983 Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature Charles Sanders University of Illinois, Urbana-Champagne Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Sanders, Charles (1983) "Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature," Studies in English, New Series: Vol. 4 , Article 39. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/studies_eng_new/vol4/iss1/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Studies in English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English, New Series by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sanders: Cohen, Comic Relief: Humor in Contemporary American Literature SARAH BLACHER COHEN, ED. COMIC RELIEF: HUMOR IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE. URBANA, CHICAGO, AND LONDON: THE UNIVER SITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS, 1978. 339 pp. $15.00. The year was 1983. Praisers of the literary imagination who believed that their praises should reflect some impassioned bit of the imaginative—those artist-critic-scholar-teacher out-of-sorts like Guy Davenport, or Richards Gilman and Howard, or George Steiner, or the brothers Fussell, for whom “excellence...is ever radical”—all these had been interned upon the new Sum-thin-Else Star. (To a neighbor ing star, rumor has it, must eventually come Sanford Pinsker, Earl Rovit, Max F. Schulz, and Philip Stevick, especially if they insist on writing with a brio that places them in brilliant relief to the twelve others with whom they have presently, unfortunately, been asso ciated.) A few remaining disciples of letters and the fine arts were now relocated in the High Aesthetic Education Camp of the One Galactic University Sandbox, Inc. -

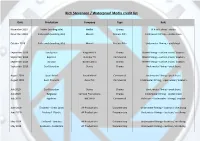

Rich Stevenson Credit List Jan 2020

Rich Stevenson / Waterproof Media credit list Date Production Company Type Role November 2019 Aether (working title) Netflix Drama VFX stills shoot - studio November 2019 Sack Lunch (working title) Marvel Feature Film Underwater filming – studio shoot October 2019 Sack Lunch (working title) Marvel Feature Film Underwater filming – pool shoot September 2019 Sandylands King Bert TV Drama Water filming – surface shoot / location September 2019 Experian Outsider TV Commercial Water filming – surface shoot / location September 2019 35 Days Boom Cymru Drama Water filming – surface shoot / location September 2019 Sex Education Starco Drama Underwater filming – pool shoot August 2019 Sport Relief Knucklehead Commercial Underwater filming – pool shoot August 2019 Avon Products Avon PLC Commercial Underwater filming – open water / location July 2019 Sex Education Starco Drama Underwater filming – pool shoot July 2019 Belgravia Carnival Productions Drama Underwater filming – studio shoot July 2019 Apple Inc BBC NHU Commercial Pole cam – Underwater Filming / location June 2019 Enslaved – Great Lakes AP Productions Documentary Underwater filming – location / lake diving June 2019 Enslaved - Flordia AP Productions Documentary Underwater filming – location / sea diving May 2019 Enslaved - Jamaica AP Productions Documentary Underwater filming – location / sea diving May 2019 Enslaved – Costa Rica AP Productions Documentary Underwater filming – location / sea diving Rich Stevenson / Waterproof Media credit list April 2019 AXA insurance Prodigious - London -

“The Grin of the Skull Beneath the Skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 12-2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Drake, Amanda D., "“The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 57. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/57 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature by Amanda D. Drake A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy English Nineteenth-Century Studies Under the Supervision of Professor Stephen Behrendt Lincoln, Nebraska December, 2011 “The grin of the skull beneath the skin:” 1 Reassessing the Power of Comic Characters in Gothic Literature Amanda D. Drake, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2011 Advisor: Dr. Stephen Behrendt Neither representative of aesthetic flaws or mere comic relief, comic characters within Gothic narratives challenge and redefine the genre in ways that open up, rather than confuse, critical avenues. -

Sport Relief '04 Media Pack

sport relief ’04 media pack CONTENTS The Sport Relief vision 2 Sport Relief ’04 – Go the Extra Mile 3 How to register 5 What to buy 6 What’s on TV and radio 7 What else is going on in the world of sport 10 What’s on the web 11 How to donate 12 What’s in schools 13 Where the money goes 14 Who’s helping 17 Thank you’s 19 Some useful facts 20 Fitness First Sport Relief Mile event venues 21 Celebrity quotes 24 Photography: Glen Edwards, Grant Manunui-Triplow, Justin Canning, Matt Mitchell, Rhian AP Gruffydd, Sam Robinson, Trevor Leighton, Vicky Dawe. www.sportrelief.com 1 the sport relief vision Sport Relief was set up by Comic Relief and BBC SPORT to tackle poverty and disadvantage, both in the UK and internationally. Its debut in 2002 raised more than £14 million, and that money is now hard at work. This time around, Sport Relief is aiming to do even better. The vision is to harness the power, passion and goodness of sport to help change the world. www.sportrelief.com 2 sport relief ’04- go the extra mile Sport Relief returns on Saturday July 10th and it promises to be one of the highlights of the summer, with the biggest Mile event in history and an evening of unmissable TV on BBC ONE. There’s no need to be a sporty person to get involved. Just sign up, get sponsored, and be there on Sport Relief Saturday to help change the world by miles. Venues up and down the country will host the Fitness First Sport Relief Mile and some of the best known faces from the world of sport and entertainment will line up alongside the public as the whole nation comes together to be part of a very special day. -

STEVE PHILLIPS Tv Editor ( Avid/ Fcp/ Premiere) 59, Maple Road, Horfield, Bristol BS7 8RE Tel: 0117 3735676 Mob: 07867 525234 [email protected]

STEVE PHILLIPS tv editor ( avid/ fcp/ premiere) 59, Maple Road, Horfield, Bristol BS7 8RE Tel: 0117 3735676 Mob: 07867 525234 [email protected] www.meboid.co.uk Freelance Experience natural history 09-12/ 2020 Our Planet: The Science. 70 min feature doc re. Johann Rockstrum’s Planetary Boundaries Framework. With David Attenborough. A Netflix Original Doc. Producer: Jon Clay NETFLIX/ Silverback 03-05/2020 Our Planet: Too Big to Fail. How finance can power a sustainable future. Dir: Dan Huertas N’FLIX/ WWF 03- 05/2019 Our Planet Our Business. How global business can drive action for nature. NETFLIX/ WWF/ Silverback 01/ 2019- 2020 Our Planet ‘Halo’. Series of online ‘Our Planet’ films, multi platform. S. Producer: Jonnie Hughes NETFLIX 10-12/2018 Savage Kingdom 3 Ep5. Predators in a kill-or-be-killed world. SP: Lucy Meadows. Icon Films. Nat Geo 10/2017 Blue Planet 2. 90min French reversion. Producer: Orla Doherty France2 05/2016 Nature’s Weirdest Events 2. Eps2 & 8. presenter: Chris Packham. Producer: Tom Payne.BBC2 06-10/2016 Wonders of the Monsoon. Ep5: People of the Monsoon. Producer: John Clay BBC2 04-07/2014 05-09/ 2013 Kangaroo Dundee. 6 part series re. Brolga Barnes, 6’7” ‘mother ‘ to mob of orphaned kangaroos. Part edited on location, Alice Springs NT. Producer: Andrew Graham Brown BBC2 09/2012- 01/2013 North America. Epic 5 part Blue chip series re. American Wildlife. Wild Horizons/ Discovery 06-07/2012 Planet Earth Live- A Monkey’s Tale. 60min re. Macaques. Producer: Andy Chastney, BBC1 08-09/2011 Natureshock: ‘Death Fog’ & ’Man Eating Lions,’ Prod: Andrew Graham Brown. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Hear Me Roar Wins Best Documentary Award!

Scan this code to view an e-edition of this paper The official newspaper of The Axholme Academy. Produced in partnership with the Lincoln School of Journalism and Mortons Print, Lincolnshire’s only independent newspaper printer. June 2016. Visit www.theschoolnewspaper.co.uk NEWS for more information. AXHEAR ME ROAR WINS BEST DOCUMENTARY AWARD! UK glory in London In March 2016, Students William McCullion, Caitlin O’Leary, Alice Balderston, Luke Slaney and Tiffany Robinson attended the Into Film By Eve Jones and Emily Armitage Awards at the famous Odeon cinema in Leicester Square London. The film was called ‘Hear me Roar’ and it was shortlisted for a Best Documentary award at the once in a lifetime opportunity to watch a debate. Into Film Awards. The film was based on William Then they made their way to the Odeon cinema McCullion and his thoughts and feelings of the ready for the awards. world he lives in. They thought it would be a good After glamorously walking down the red carpets idea to base it on him as William is a very intelligent with celebrities and sitting and watching clips of the and he sees things in a different perspective. He films which were made by their opponents, they is also a member of Youth Parliament for North were very happy and proud to see that they had Lincolnshire. actually won the award for Best Documentary and Into Film gives every child and young person astonished to learn that their work was up against aged 5 to 19 in the UK the chance to experience 1500 entries and they still won! Kieran Bew who Above: Mr Brooks with the students film creatively and critically as part of a rich and recently starred in ITV’s Beowulf presented the and their award! well-rounded education whilst also learning skills they can use to build a career in the film industry award to them on stage where William presented if they want to. -

Ebury Publishing Spring Catalogue 2019

EBURY PUBLISHING SPRING CATALOGUE 2019 The Healing Self Supercharge your immune system and stay well for life Deepak Chopra with Rudolph E Tanzi Combining the best current medical knowledge with a new approach grounded in integrative medicine, Dr Chopra and Dr Tanzi offer a groundbreaking model of healing and the immune system. Heal yourself from the inside out Our immune systems can no longer be taken for granted. Current trends in public healthcare are disturbing: our increased air travel allows newly mutated bacteria and viruses to spread across the globe, antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria outstrip the new drugs that are meant to fight them, deaths due to hospital-acquired infections are increasing, and the childhood vaccinations of our aging population are losing their effectiveness. Now more than ever, our well-being is at a dangerous crossroad. But there is hope, and the solution lies within ourselves. The Healing Self is the new breakthrough book in self-care by bestselling author and leader in integrative medicine Deepak Chopra and Harvard neuroscientist Rudolph E Tanzi. They argue that the brain possesses its own lymphatic system, meaning it is also tied into the body’s general immune system. Based on this brand new discovery, they offer new ways of January 2019 increasing the body’s immune system by stimulating the brain 9781846045714 and our genes, and through this they help us fight off illness £6.99 : Paperback and disease. Combined with new facts about the gut 304 pages microbiome and lifestyle changes, diet and stress reduction, there is no doubt that this ground-breaking work will have an important effect on your immune system.